More and more researches explore the roots of the history of Eastern European queer culture. More than a quarter of a century has passed since the system change; still we just started realizing that our referential point against heteronormative history writing is not Stonewall. Recently a conference was held in Paris to present “Communist Homosexuality,” that is the period before 1989. Karol Radziszewski, who accomplishes solid work in this field, also held a lecture. With his more than ten-year-old fanzine project, DIK Fagazine, the Polish artist visits post-socialist countries one by one, from the former Czechoslovakia to Belarus, in order to report on the progress of each place’s homo-culture of recent past and present. Although we still await for the publishing of the Hungarian edition of DIK – who knows how long – two documentaries have been shot recently about gay and lesbian circles existing behind closed doors of private apartments and secret clubs during the Kádár-era in Hungary.

The present essay introduces two artists who do not enrich the material of such researches. By introducing briefly the performance art of El Kazovsky and avant-garde fashion designer Tamás Király, I wish to point out that what we call queer today in the widest sense – that is the idea attempting to eliminate socially constructed boundaries of body and identity – was not unknown before 1989 on this side of the wall. The question is whether it is worth to include the autonomous art practice into a theoretical scope that had been formed based on and motivated by a different social-political context.

Let us begin with the definition of queer in present-day Eastern Europe, and with the reason why this term is problematic! The book of Polish authors Robert Kulpa and Joanna Mizielinska, entitled De-Centering Western Sexualities (2011) is the first that points out by collecting locally relevant sociological points of view how much Socialist past affected the here and now of queer culture. The reason for the lack of the rainbow-coloured, keen discussions is simple: desires, behaviours and lifestyles differing from the heterosexual were taboo for more than four decades, and were even considered illegal in some Socialist countries, until 1961 in Hungary among them. While in the United States the gay liberation movements and lesbian feminism led to queer theory in academic circles in decades, the critical discourses on gender reached only a few people in Eastern Europe – and only in the form of samizdats and xeroxes.

This changed abruptly with the system change: as more and more mostly short-lived gay and lesbian organizations emerged, the LGBT acronym started to be recognized by the public. It is another interesting question what the Q of the queer means at the end of the acronym. According to theoreticians, an important difference is that LGBT stays with the subject matter of sexuality, even strengthens the boundaries of identity, while queer contemplates on the elimination of these boundaries, as an intersectional approach of normative systems surrounding the subject. Even though the Q in theory attempts to subvert the forms of identity represented by the acronym (that is, it opposes the categorical nature of the preceding letters), today in many cases it increases “confusion” in Hungary: it is understood mistakenly as an umbrella term or simply as a synonym of gayness. Not only it is clear from this how the progressive and outdated theoretical approaches from the West mix in Eastern Europe; Kulpa and Mizielinska also point out that queerness might be the label of both the developed (West) and the belated (East) in academic discourses. Moreover, in activism it can paradoxically become a category of identity politics, even though in our daily lives abstracting the body immensely can hardly be reconcilable with the real experience.

Since art is originally a field of abstraction, I do not consider it essential to group artistic practices according to different theoretical approaches. There were artists in the Socialist Hungary, as well, who expressed their fantastic visions through constant reinterpretation of the limits of body and identity. They are special because the subject of their art is not the norms and conventions dictated by society, but still, the socio-political context gets a critical underscore in their works: the existing frames seem to be too tight for their ideas not to break the rules.

It is strikingly obvious, and an interesting topic from a social historical point of view, how could cross-dressers or kissing boys appear in the seventies-eighties in public theatrical performances. However, what I consider to be the most interesting is that certain artists were able in the grey reality of Socialism to create a world in which the members – even if temporarily – were free from the rules of the authority. They did not break down their own limits continuously but with their mere presence they pushed the verge of freedom farther and farther.

Tamás Király (1952-2013) made it sure in several ways that his art did not fit easily in either of the already existing categories. The fashion designer appeared in the underground art scene of Budapest in the beginning of the 1980s, and created something that hardly existed in the region before.

During his inner city fashion walks, the models shocked the passers-by in litterbag-cocktail dresses. Another time the dome of the Parliament and the red star on the top inspired him to create a hat, and they took photos in it on the streets of Budapest. With his costume designer friends, he ran New Art Studio, a punk boutique and underground meeting point, where he put humans instead of mannequins in the shop window, in order to unsettle the passers-by. Inside jewellery made of a pheasant’s leg, geometric mirror pins, tar-board vests and other treasures were sold in the name of DIY.

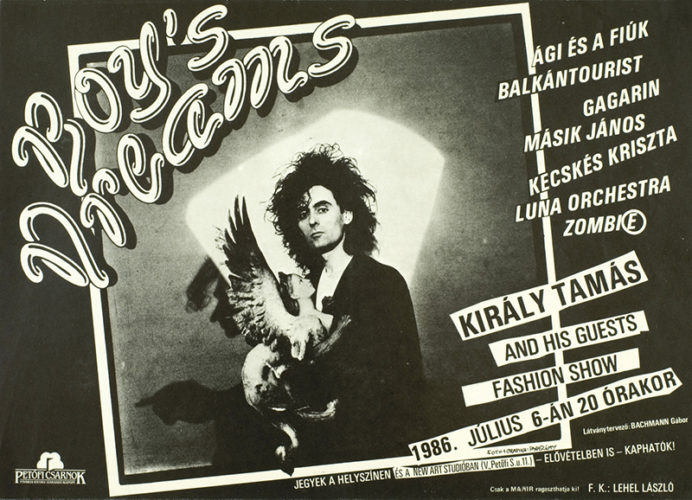

From the second half of the eighties he staged his grand fashion shows in the concert venue called Petőfi Csarnok (Petőfi Hall), where at the time international stars like Allen Ginsberg, or Nico performed. Each show presented almost a hundred creations to his audience of a couple thousand alternative young people, accompanied by the most progressive new wave bands. Models in red star dresses, animals, ancestress and body builders filled Király’s dreamland. Today the Hungarian fashion world still distances itself from his clothes sculptures that extend the limits of the human body, and from his shows unfolding into feverish dreams with unusual models. As an autodidact in his time he had not been officially recognized. Despite all of this, Király’s collections were shown on the catwalks of West Berlin, Amsterdam, and New York before the system change of 1989, and his first successes were noticed by i-D and Vogue.

In 1988 he showed a geometric black velvet collection of almost forty pieces in Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, together with the world’s seven leading avant-garde fashion designers. In the Dressater show Király presented his works together with artists’ like Yoshiki Hishinuma, Rudi Gernreich or Vivienne Westwood. Models were walking along on a steel-plate hanging in the desolated train station in pyramid-, ball- and disc-shaped garments. The collection recalled Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, its red and black colours evoked Russian constructivism, and the models’ workers’ boots implied the everyday life in Socialist Hungary. The most remarkable however, is the way Király treats human body as a rewritable, transformable surface, already in his earliest works. This attitude ties him to such figures of postmodern fashion like Westwood, or Jean Paul Gaultier, who also had enough of the limited vision of the fashion industry reinforcing social roles in these same years.

The painter, performer, poet and costume designer El Kazovsky (1948-2008) of Russian-Hungarian origins deals with the questions of gender identity much more concretely. This makes it harder to understand it, though. For decades, the artist constructed an individual narrative in his paintings, interviews and the performance series Dzhan panopticon. One essential part of the story is his transsexuality and the insatiable desire for another body arising from it. We also get informed from Kazovsky that the theatrical panopticon-series shows an important meeting in his life, for which he creates monuments almost yearly between 1977 and 2001, in different venues. The script is always the same, only the set changes: the audience sees the story of Pygmalion and Galatea from Ovid. During the commemoration the meeting activating this “personal timeline” gets abstracted by the presentation of the relationship between the creator and the fetish. Kazovsky plays the role of Pygmalion in the performance. According to the artist’s own interpretation, identifying himself as a homosexual man born into a female body, this indicates the way he attempts to give a soul to the perfectly feminine male body.

The question presents itself: were the details of his personal life appearing in the interviews – that is the transsexuality of Kazovsky – relevant when approaching the oeuvre? The answer, however, is not at all simple. The confessional character of his statements and the fact that he has the same point of view for decades, hardly ever interrupting the narrative built around his art, implies that the two might be handled together. This is what the curators of the oeuvre exhibition (The Survivor’s Shadow), displaying hundreds of the artist’s works, did in 2016. It may be considered to be a step forward that this could have been realized within the walls of the Hungarian National Gallery. Apart from the Trans-Sexual Express (2002, Kunshtalle, Budapest) and The Naked Man (2013, Ludwig Museum, Budapest) exhibitions, such large institute had not dealt with the subject of transsexuality so explicitly. However, if we disregard the personal aspects of the oeuvre, it is still noticeable that in Kazovsky’s universe, which he constructed for long years, inhabited by lonely male torsos, Greek mythological figures, and sharply painted dogs, there is no place for the expectations of the society of his time. It must be exciting as an art historian to unfold the gay cultural references of the pieces, and we can guess during which travels and through what literary experiences the artist had arrived at them. It must be admitted that Kazovsky’s world is as self-referential as it can be, tied to certain subcultures’ aesthetics. His artworks do not reflect on the habits of a specific society, but he simply leaves them out of consideration when expressing his artistic vision.

The works of Kazovsky and Király have no forerunners or followers in Hungarian art. While a cult has been built around the macho artists of the underground, they created an alternative reality for themselves. They looked at the world from a broader standpoint than the one existed then and there, and international references/parallels can evidently be found in the art of both of them. In the case of Kazovsky, for example, the camp-sensitivity and his passion for punk is undeniable – the evidence for this, apart from his works, are the countless Sex Pistols and David Bowie posters, album covers and pins that he treasured as sacred objects at home, together with the books of Susan Sontag. They are unique rather because of their autonomy. They were not engaged in one trend but they picked from the codes of culture according to the needs of the realization of their own visions. Király’s red star dress was not necessarily a gesture of criticism of the system on its own. He used vacant symbols of Socialism as toys for realizing his dreams because in a sense they did not mean anything for him.

If we do not use the term queer for one movement or culture – because it would require the fulfilment of certain criteria – it would be a good starting point for the fragmentary description of inverting existing norms. However, we do not necessarily need to adapt this inherited approach. First, because the two presented examples balanced on the edge of a different scene where the art world was under surveillance, and the authorities controlled the artistic expression. Abstraction, namely presenting something differently than it really is, for example in the Socialist system also meant a kind of protection against censorship. Moreover, because delicate moments of border crossings cannot be precisely apprehended – especially not based on theoretical concepts. The sovereignty of the art of El Kazovsky and Tamás Király originates in the inexplicable secrets within, and because of this it resists the systematizing means of interpretation.

Translation from Hungarian to English by Eszter Greskovics.

POSTED BY

Gyula Muskovics

Gyula Muskovics is an independent curator based in Budapest. He worked for tranzit.hu as a curator and researcher from 2013 to 2017. He was the editor of contemporary art magazines tranzitblog.hu and ...

Comments are closed here.