This text aims at introducing an exhibition that lures (me) into more or less inspired remarks on the status of the „Romanian contemporary art scene” (which has received lots of attention lately) or that of the National Museum of Contemporary Art (likewise). The local art world, very much taken with itself, is divided in sets, subsets, processes and directions at times apparently self-sufficient, other times anachronistic, it gets scattered in gestures and events with a temporary effect, in which resources and energy are being invested without long term perspective or vision. Though it’s good that in Romania we don’t have only one artistic “center”, but many micro-scenes, at present they work separately, with too few (inter)connections or contributions to joint projects. There are those areas and initiatives that break free from this attitude and practice a critical approach or try to collaborate inside collective structures, yet in these cases…almost always a “yet” state is being reached.

I was happy that among MNAC’s most recent exhibition season was featured one dedicated to the artistic community from Iași (sharing a floor with the R.E.M.X. show, the itinerant version of Media Art Festival Arad’s second edition), not to the entire artistic scene from Iași but focused on that core formed in the 90s around the Periferic Biennial and the Vector Association on account of a mutual critical practice and attitude. A winner of the 2015-16 exhibition call, the In Times of Hope and Unrest. Critical Art from Iași makes visible the work of some of this micro-community’s significant artists, on the backdrop of the group’s intense and also early activity, as well as their strategies towards (self)representation in a state institutional context, with its pros and cons.

Though I’m not entirely free from the temptation of contextual digressions, I’ll (re)turn to the content – the main reason of this review (and perhaps of any review). The exhibition’s curators, Cătălin Gheorghe and Cristian Nae, (obviously) insiders of the Vector artistic community, have weighted well their selection of works while smartly confronting new, large-scale installations with the “historical” part from the space dedicated to the Vector micro-archive (which contains the critical publications and projects developed inside the Vector Platforms between 2007-2015, among which the Periferic Biennial 1997-2008, Vector Gallery 2003-2007, Vector Publishing 2005-2015, Vector-Studio of artistic practices and debates 2007-2015, etc., or in initiatives such as Vector Art Databank, an artistic and research project/archive curated by Matei Bejenaru and Cătălin Gheorghe, the program Carte Blanche Aux Jeunes Créateurs dedicated to young artists from the Moldavian region or from the Republic of Moldova, supported by the French Cultural Centre from Iași, etc.), bringing together the past, present and – somewhat implicitly – the future of the group.

The resulting display is monumental, spirited by the tension between iconic representations and moving images or performativity. Besides the aesthetic effects and the underlining legitimising strategies, the curatorial approach (a collaborative one as well) manages to present a coherent synthesis on the Iași group’s specificity and diversity. First of all, the central common direction is given by the reference to the (quite loose) notion of critical art, used in the sense of social practice, of socio-political-economical engaged art. From Liliana Basarab & Bogdan Pălie’s 2014 Repetition video, that reshapes in a staged manner the socially-built roles of the policeman-the authority vs. the activist-the opposition in the setting of an ex. Romanian Secret Service’s headquarters’ terrace in Iași, to Dragoș Alexandrescu’s 2013 Before Was Better video that in an almost cinematic approach shows the intimately profound effects inside the Romanian emigrant workers’ families and especially on their children, all the standpoints from the exhibition are critical against some aspects from the local context and the power structures that cause these realities.

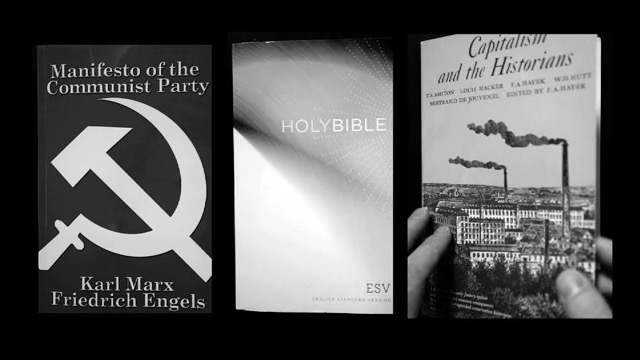

Some works focus on meanings available to larger audiences, with comparisons to the local society and geopolitical context, such as Cezar Lăzărescu’s 2015 Playground interactive installation, that invites the public to play with military toys on folk Romanian carpets, referring to the increased militarisation in Romania in the midst of recent conflicts in the area and on behalf of the NATO membership, or Dragoș Alexandrescu’s 2013 Exercising Failure video, that makes use of commonplaces (the tearing of the books, the blond and pure little girl, the post-industrial dystopian setting) in an elaborate plot in which the (literally) knitting together of some of humanity’s most influential ideologies and books (Christianity/The Holy Bible, Marxism/The Manifesto of the Communist Party, neoliberalism/Capitalism and the Historians) weaves the past, present and future of human civilisation – destined to failure when these paradigms aren’t transformed, rephrased, appropriated in a more personal, human way.

The show’s scenography unveils the group’s internal structure, at its center standing Matei Bejenaru (the founder of Vector and Periferic) with a video installation on 5 channels that shows various stages of his Songs for a Better Future project. Started in 2010, it comprises a series of video documented performances resulting from the collaboration between the artist and a musician invited to compose and conduct a choral piece inspired by its specific political and cultural context (from Bucharest, London, Timișoara, Innsbruck, Haga). The solemn, dramatical and monumental setting of the choir’s performance emphasises the script of these compositions, drawn from site-specific utopian visions of the future (for example, the Bucharest show worked with Romanian songs from the Communist era that glorify work and workers).

What the exhibition doesn’t do and hasn’t even explicitly planned on doing is institutional critique, or at least a critique addressed to the present anxieties of the engaged context. This comes across though, indirectly, mediated through its vicinities. Dumitru Oboroc’s Planking Art 2013 series of photographs, through which the artist tests the socio-institutional conventions and the reactions or effects of a potentially disturbing performative gesture inside Viennese museums shows a type of critique strictly confined to those coordinates. Dan Acostioaei works (all form 2015) are perhaps the only ones from the exhibition that critically deal with the present frame, not the art world’s one, but that of its nearness to the religious field and especially the spatial proximity with the People’s Redemption Cathedral. His video Blowing in the Wind shows a kite with the face of Christ flowing above the cathedral’s construction site near its much larger Banner version that overlooks the exhibition space with its terrible mixture of Christian iconography and Communist propaganda aesthetics. The critique of the Romanian Orthodox Church’s real and excessively displayed power goes further in the Logos installation, conceived like the signage of a range of services offered by saints, angels, The Holy Mother and the Child and Christ himself, all represented in a flat, simplified, advertised manner on blue light-boxes fit to serve the nearby future religious-mall.

Least but not last, the critical projects developed in the contemporary art from Iași inside and around the Periferic-Vector micro-community are brought forward as already historicised (especially in the archive and documentation area), besides a future potential to generate new standpoints and reflections. As for the unrest announced in the title, I experience it in regards to the Romanian social and political context, but especially when it comes to the artistic one, in the field of contemporary art production and exhibiting, that still faces a precarious support. Is there hope? The work done by the group from Iași and gathered in the Vector micro-archive suggests so and helps us to believe in the heroical scenario in which the critical spirit and artistic creation are possible against all contextual, institutional or practical odds, setbacks and shortcomings. Let’s keep up with hope then, as always.

In Times of Hope and Unrest. Critical Art from Iași, Curators: Cătălin Gheorghe and Cristian Nae, Artists: Dan Acostioaei, Dragoș Alexandrescu, Liliana Basarab & Bogdan Pălie, Matei Bejenaru, Cezar Lăzărescu, Dumitru Oboroc, was at the National Museum of Contemporary Art between 26.11.2015 – 20.03.2016.

Special thanks: Sandra Demetrescu, the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) Coordinator of the exhibition

POSTED BY

Diana Ursan

Diana Ursan (b. 1988) writes about art, mainly contemporary art. She has contributions in Arta magazine, Observator Cultural and in Dear Money, book edited by Salonul de Proiecte and The National Muse...

Comments are closed here.