Raluca Voinea is one of the most respected curators on the Romanian scene, activating via tranzit Bucharest, as well as independently, in projects that question the public space. Through her work, Raluca facilitated for numerous artists the access to vital resources and has represented an ethical stance in a generally difficult context.

I see this series of interviews as a document that could help young people learn how to become curators. This is why I would like to start with your studies.

College is the most painful subject of all. I studied AHT (Art History and Theory) at the end of the 90s – a school belonging to the category “what to to do when you’re not interested in your livelihood, when your existence does not depend on your studies”, all very elite, 10 spots in the whole country, serious entry exam, you could’t get in with just your baccalaureate grades, there was no mandatory reading list, just the possibility of practice – hopefully with someone who could intervene in the selection process, although this wasn’t my case, but I did prepare with someone that knew the requirements (Ruxandra Ionescu, the director of Ploiești’s Art Museum and a teacher at the Art High School; unfortunately she suddenly passed away shortly after I graduated so we never had the chance to further discuss my experience). Surprisingly, I got accepted on my first try. I had just finished 5 years of pedagogical high school – I had a secure workplace, this is why I could choose to study there, I had nothing to lose. I gave up the teaching position I was offered and enrolled full time; with my parents’ support, I did not have to work.

But college turned out to be like nun school – something I will never forgive. Everywhere you looked there was medieval art, visits to churches not just for the iconography, but for the dogma as well…

It was pretty sad: on one hand you had a myriad of possibilities, on the other hand there were too few people that could help you navigate these possibilities while you were forcibly fed the same type of food ad infinitum. If you suddenly started complaining in your forth year you were met with reproach – for example if you had something to say about Răzvan Theodorescu’s excessive number of courses within the university.

I hope things are different now: there is another dean, there are new people. For example, back then there was a single contemporary art course with Mr. Adrian Guță; there was no system for optional courses, there were no parallel courses. The internet came to be when I was finishing up my studies; back then Romtelecom would bill your waiting time in addition to the time you actually spent online: information was literally very expensive. It was obviously a shock: after years of studying Byzantine or Renaissance art with black and white projection slides, one could find a much bigger world online.

There was a small compensation: the trip to Italy. But it was no different; to get an idea of the general interest for contemporary art: we went to Venice in a Biennial year, but earlier in the year before the opening. We saw mosaics and frescoes, all in byzantine style if possible. It was an eye-opening trip; for many of us it was our first time abroad.

When you realize you are more interested in contemporary subjects and there is no one to turn to for advice, you make it on your own. One finds books, one book leads to another, but there is no one there to shed some light. For me, it was the French Institute where I was able to find the books I needed.

Did you visit art exhibitions as well?

There were very few and I wasn’t in the habit of visiting them. The MNAR collection wasn’t even open because the building was being renovated at the time. I didn’t visit artist studios that often either, only when there were open studio days; I wasn’t in the habit of directly visiting artists and catching up on their work. At least our department was within the University of Arts: it did not matter that we only had partial contact with the other departments, at least you felt that your studies were related to artists and art works. But we rarely communicated with “craftsmanship” students (haha, I haven’t even looked up whether it’s still called that). I can’t remember if the photography and video section was up and running back then; can’t remember when the NEC was founded but I remember I went to a few conferences there, maybe after I graduated.

So you got to contemporary art via books.

Mostly yes, and it already was passé art: when I was reading ArtPress, the art I read about was already classic. I remained in the theoretical zone for a long time because I lacked sufficient information on artists or works to have the confidence that I truly understand them. I wrote my bachelor’s paper on aesthetics, on the sublime. I was the only one who ever wrote their paper under the supervision of the Aesthetics professor who was generally disliked because his course was the analysis of The Critique of Judgement.

The curriculum structure wasn’t to blame, it actually gave you a broader perspective which you couldn’t get from somewhere else. But the lack of people and resources to back up these courses was depressing. In the meantime things changed and the University started catering more to the students rather than the professors who had to teach there indefinitely.

When did you break away from the academic context?

When I met Dan and Lia Perjovschi. Their studio was located inside the University, but I never got to visit it during my studies. I spent two years around them, a time when I recovered everything I lacked during school. They were my door to everything contemporary, but I was also exposed to a completely different approach: you are no longer competing, you are in a place of knowledge where it is more important to share than to keep for yourself; art is not an isolated place, it is linked to everything else; the art space is one of generosity, curiosity, change and constant learning.

I met Dan and Lia in 2002 when Edi [Constantin] and I proposed them to do an interview – we wanted to make a series of filmed interviews with contemporary artists; I went to their studio and the first meeting lasted six hours. I went together with Edi and a room mate, Oana Râpeanu, a film student, who had a camera, a VHS I think.

In the meantime you had graduated. Did you start you working in the field?

It took me about a year to figure out what I wanted to do. Then I got a job at MNAR, in the recently opened Education department where I remained for two years. It was a mostly boring job: the ones who usually solicited guides were official delegations who only checked the visits in their to do lists, they weren’t really interested in what they were seeing. The museum’s collection was always the same; I found a small avant-garde display to be interesting, but unfortunately it did not attract too many visitors. But overall it was ok, the department was young, we were all the same age, there was a certain energy; my office was in the attic with a view towards the Palace Hall, we had plenty of ideas, we would also do education programs for children where we did our very best. I worked with Angelica Iacob and Doina Anghel who later became my colleagues at E-cart.ro (Angelica was actually the co-founder of the E-cart.ro association; together with Edi, they took care of the papers back when I was still in London, we worked together for a long time). In any case, the department grew and it became one of the first in the country that experimented with all kinds of museum educational formats. Raluca Bem Neamu, who ran the department for many years, together with other colleagues, still work in the field, are part of NGOs or the private sector (those who left MNAR).

How did you end up at the Curating MA program at the Royal College of Art in London?

In 2003, a group of Royal College students came to Bucharest together with Claire Bishop to see the Iași Peripheral Biennial as part of their foreign journey. Lia Perjovschi invited all of us to dinner at the TNB terrace, The Motors. Claire told me about the course and asked if I wasn’t interested; it all seemed sci-fi to me: the idea of curating, the idea of taking this course and the idea of London. During the same year, in September, I went to the Istanbul Biennial.

Meanwhile, we (Edi Constantin, Simona Nastac, a programmer friend, Mădălin Geană and I) created the online magazine e-cart.ro; we made this decision on our way home from the Peripheral, when we realized that someone needed to talk about it. We still solemnly keep a piece of paper with the summary of our first issue that Simona, Edi and I wrote on the train ride home. The magazine was online from the start, we knew we could not afford anything else. It was a way of learning about contemporary art by directly writing for the magazine, inviting artists and critics to write and translate texts (the magazine was bilingual from the beginning). Obviously, everything was self-thought, including our navigating through the virtual world, accepting its limitations (I remember during our first issue, the website would constantly crash because there was a cleaning lady who always unplugged our server when she cleaned up).

But coming back, I met Claire in Istanbul during one of the Biennial parties. I kept in touch with her and she asked me again if I wasn’t interested in applying for the masters program. Sometimes it doesn’t even matter how badly you want to do something, but rather what counts is that someone encourages you to go into one direction. Mrs Ruxandra Ionescu, who trained me for art school, along with Lia and Claire were the people who showed up in my life at the right time. So I applied, I went to the interview and I got accepted on the spot, problem was how to pay for it. I found a scholarship via the Ion Rațiu foundation that helped with the rent and food, but there was still the problem of the college tuition. Romania wasn’t in the EU at the time and we were seen as overseas: the taxes ranged to tens of thousands of pounds per year.

I thought this course was totally supported financially at the time and it was only recently that this ceased to happen.

It was financed in the sens that there were a lot of money for the course and scholarships for British and EU students, but not for the ones overseas. I waited until the last possible second, I was only able to obtain this living expenses grant via the Romanian subsidiary, but it was already August and if I wasn’t there in September on the first day of enrollment, everything was lost. I was in Câmpina when Claire called to tell me to get my visa, that everything would be ok. Teresa Gleadowe, the course’s director, found a way and a foundation would cover my tuition fees.

I am surprised to hear RCA sponsored students. They wouldn’t do the same today.

Teresa was the one who managed to make up the most international course in RCA history. But all that changed soon after she left.

It all happened very fast. Thursday I went to get my visa, I didn’t get it so I went again on Friday; meanwhile, Teresa called the embassy and that’s how I got the visa, otherwise I wouldn’t have been able to prove that I had sufficient funds to support my stay in London for two years. On Saturday I packed my bags and left on Sunday. I had no idea where I was going to live. I was lucky with Simona [Nastac] who got accepted at Goldsmith and was already settled in London, so I stayed with her for my first week.

Was RCA brilliant?

Yes, I think we should have a separate discussion about this topic! At first, there was nothing I could compare it to. It was all very fine, but this was a system that prepped you and offered a lot of opportunities if you chose to remain there. I graduated in 2006 and if I stayed in London for a while longer, it wouldn’t have been so difficult. But I didn’t want to stay there anymore, it was clear to me that I needed a break from London. I took an internship at the Van Abbemuseum, then I returned to Romania and shortly after I took this job with Marius Babias for the project Bucharest public space 2007, which lasted a year. The Goethe Institute was the main organizer and I finally had a well paid job that enabled me to move back to Bucharest and work in the field.

It may sound dramatic, but back then it was impossible to stay in London even for a week after graduation with no money. No job was enough, you needed livelihood to live.

At the same time, my internship was paid by the college with the possibility of getting hired after; some of my colleagues found work in the field right away – entry-level jobs, not as custodians, but decent positions nevertheless. But I, for one, felt that I don’t belong there, that I can do something more motivating. The experience itself was also very tiring: the fact that the school was paying for my taxes came with certain obligations, the course was basically a full-time job. I was lucky I didn’t have to work, to have side jobs, but everything was very precarious, I needed a break.

You had a big graduation project; did you work on other independent projects during the course?

No, I only did projects via school, I didn’t venture on my own. The final project was a group exhibition called Again for tomorrow; we were 13 curators and we chose 13 artists after a tough negotiation process that ended up in tears and blackmail. The exhibition was at the Kensington gallery, we even had public programming.

The process of organizing the exhibition involved all the activities we learned during the course, from visiting exhibitions and openings to taking trips via the course. At the end of the year we had to decide where to go: some of my colleagues went to South America (Argentina and Chile), while the four of us who remained went to Eastern Europe for three weeks, from Istanbul to Budapest to the Balkans, with all means of transportation. For me, it was my first time visiting some of these places like Sofia, Tirana or Skopje. It was interesting from a practical and theoretical perspective: I ended up back in my region via this London detour. I read Marx for the first time in London, I had to go to London to be able to visit Sofia, I went to London to write about the East because my master’s dissertation was about Eastern European exhibitions.

During this trip I met part of the artists selected for the final exhibition. We had an immense budget, 40.000 pounds if I remember correctly, and the selected works were very good, the exhibition sustained itself as a whole, the links between the artists were not random, we had discussed every detail beforehand – basically, there was no possibility of failure with this project. Usually, the RCA exhibitions were not seen as student exhibitions.

What do you feel you’ve gained after this course?

The completely different way of working compared to UNArte. We had round table discussions instead of courses where we just sat at our desks and listened; Teresa would invite specialists that were passing by through London each week to talk to us about their practice. It was fascinating but it also got frustrating after a while – I was at an age where I wanted to act rather than to just listen to other discourses. But the fact that I had contact with these people gave you numerous perspectives, I realized there were no formulas, no sure way, there was nothing more important that something else in this field so I could do absolutely anything, from working in the public space to working in museums, small galleries, radio shows or publications.

I gradually detached myself from this college because I realized that it was operating in a very western and very established context and if you wanted to do something else, what you learned or the people you met weren’t of much help.

One thing is certain, RCA makes you a professional.

On the other hand, the school did prep you for that specific reality, but only a certain kind of reality because it was part of an elitist bubble. I would take the 38 bus from East End to Kensigton everyday and I would pass through all these other parallel realities, I would see the border behind which everything was changing and I could clearly see where this school belonged. The London experience was very important, so was the fact that I lived in various areas of the city.

Tell me about the first project you were involved in after you returned to Bucharest, Bucharest public space 2007.

I was to project coordinator, meaning the person in charge of everything. The project was curated by Marius Babias and Sabine Hentzsch, they invited the artists. It lasted nine months and had various components; there were spring activities – a conference that launched the project – then we launched the website that was managed by Edi (who also designed it) and I, published by E-cart.ro. Then we had the projects during the fall. The artists were Romanian or from Romania, the projects were commissioned either for the city, or in the vicinity of the public sphere – for example h.art coordinated a space for projects that was open daily, where they bought groups who, at the time, were pretty marginal and invisible, to talk about their rights and ways of making it in a patriarchal and hateful society.

Daniel Knorr produced our most pop project: he marked four regular trams with the logos of four institutions which, at the time, were seen as trustworthy by the population, according to the statistics, The Army, The Police, The Orthodox Church and The Red Cross. It wasn’t a guerrilla project because we were granted the permission. Dan Perjovschi’s project in the University square was a living monument that embodied a miner and a student who took various stances against each other for a few hours each day. This was a time when miners were still demonized and seen exclusively through the perspective of the social class gap, forever at war with “the intellectuals”. This project distanced itself from this narrative and suggested another perspective that was closer to human reality, I would say. Lia Perjovschi wrapped up her Contemporary art archive and placed it in boxes – they were actually being evacuated from their workshop at the time, it was a closing chapter and we made part of this process public within this project. She did this wrapping up by going through the methodology that kept the workshop alive: an open workshop that was constantly visited by people.

Mircea Cantor’s contribution was the book The silence of the lambs that documented the lamb slaughters of Easter in villages.

Anetta Mona Chișa did an intervention on a billboard: a short film with a girl, perhaps of Roma heritage, with an aggressive attitude who shouted “What the fuck are you staring at?”. On the street there was a board with the subtitles placed in a busy intersection that would immediately draw attention. Furthermore, the clip was integrated in cinema as part of the commercials before the movies, it had a different impact.

Did this project have a remarkable impact?

I don’t know, or it did not have the impact we would have wanted, not right away at least. The impact was tangible in the relationships between the participants, some long term. We had no tools to measure the impact on the public, we should have asked, for example, the people who rode the tram. We made a documentary and asked some participants about the project but I don’t think this has any sociological relevance.

Goethe was supporting this project when Romania was entering the EU and Germany was presiding over it. We had funding from various sources: from Allianz Kulturstiftung, from ICR who was under Patapievici at the time, who was very open. It was a pilot project and Marius’ wish was that a Romanian institution would take over the idea and transform it into a permanent institution where public art does not just involve statues on horses or tricolor benches. Nothing like this was done for a long time.

I had a very good relationship with Marius, he wasn’t just a simple handyman, on the contrary, we did a lot of activities that I myself did later as a curator. I was involved in all the projects from the start. It was an important experience: Marius had a different working style from Berlin and this was my first real job in the field. I was trying to use my experience as a museum mediator to negotiate with the state institutions but I realized it was impossible: it’s one thing to mediate a 19th century painting and something else to mediate a project in the public space that doesn’t even exist except in the form of a sketch when we presented it to the authorities. People are not in the habit of imagining something that does not exist yet and are used to say no, it’s more simple. But with all the institutions backing us up, it wasn’t so hard. Oana Lăpădatu, project assistant at Goethe, was also involved; she did the contracts and general bureaucracy – all the activities that take up most of my time that I fortunately did not have to perform.

I tried, in a symbolic way at least, to take Marius’ idea further: when I returned from Berlin I founded The Department for Art in the Public Space as part of E-cart.ro.

What was your Berlin experience?

I had a six months scholarship to work for the Berlin Biennial as assistant curator. I arrived pretty late – I got there in January and the Biennial would start in April – so I only caught the end of the organizing process, when things were already settled so I did not really find a role for myself. The grant was from IFA, a foundation in Germany that granted scholarships for curators, researchers, museum professionals to visit a German institution for six months. The institution applies and then sends the invitation your way. During each Biennial, the Berlin folks would attempt to bring someone via this grant so they wouldn’t have to pay them.

It wasn’t what I imagined. I worked with Adam Szymczyk who turned out to be a very difficult person, the kind of moody star curator. And because I arrived so late in the preparation process, Adam found me a project which I would handle and have autonomy over. In one of the Biennial spaces, the Schinkel Pavilion, there were six exhibitions curated by artists. They already worked within the Biennial and had been invited to answer with a project for the practice of an artist from another generation, some of which weren’t even alive anymore. It was a difficult pavilion with glass architecture which was hard to integrate in a contemporary art project. One of the most interesting aspects of my work there was my collaboration with a team of technicians that installed the exhibitions. I didn’t do much, let’s say I supervised the entire process and I sometimes mediated. If you are working with good artists who know what they want and a production team that is not only ready in time, but also finds solutions, there’s no point in getting too involved; instead, you learn a lot, you use that time for research and dialog with the artists.

And sometimes it is very interesting to take part in the intimate work process of a good artist.

During that trip with the RCA group in Eastern Europe, I went to Mladen Stilinović’s apartment. He told us about the 70s space that he was managing: his principle was to give the key to the artist and return during the exhibition opening. This was my curatorial principle for a long time.

In 2010, when I started to be interested in curating, in Bucharest there was this idea flying around that a good artists does not need a curator.

Unfortunately, the curator ended up playing an important role in the life of an artist, but I don’t think this was the initial role. Initially, the curator of a museum would take care of the works belonging to artists who were no longer alive; then, their role was not to influence what artists do and what they display, but to maintain a link between the fragile art world – which is sometimes self-sufficient and other times it is in danger of being attacked by all kinds of demons – and the the rest of the world. I think the most interesting aspect of a curator’s work is the way in which they maintain this link: the institutions you build in order to make this link authentic and interesting for yourself as well as for others while avoiding to instrumentalize the content.

There are various contexts in which one can do a curator’s work: one can work with archives, coordinate group exhibitions where coordinating the artists is an important part, organizing live events… I suppose you have all these options at hand at tranzit, not just the option of leaving the key to the artist and coming back on opening night. So after Berlin, did you start handling tranzit right away?

It was an intermediary moment when I tried to continue my public space project. I also created a symbolic frame, The Department for Art in the Public Space which was evidently a hint at Departement des Aigles as well as self-irony: what should have been handled by an able institution with real funds was managed by us, an association with no resources. We received some small funding from Goethe and ERSTE and that’s how we were able to make a few more projects, one of which is still very dear to me. It was going in the same direction as the Public Space projects, but it was more poetic. Together with Peter Szabo, we went in front of some Bucharest, Ploiești and Sinaia factories at 6 o’clock, when everyone starts work, for three consecutive days and held fireworks. Peter had a megaphone and would wish everyone “Good morning, have a nice day at work!”. People had very different reactions because there were totally different cases. In Bucharest we were at Apărătorii Patriei at the Vulcan factory where there weren’t too many workers left; we had an initial shock because the waves of workers, like in the Lumière film, were missing: workers arrived one at a time with the bus. There was also a RATB depot so the main spectators were the bus drivers. In Ploiești we visited a factory that was still properly working, there were a lot of workers, the atmosphere seemed suspended in time, as if nothing had ever happened, no privatizing, no lay-offs. We were right across the street from the entrance, people would stop to ask us what we were doing, they were amused. In Sinaia there was another weird situation: we visited the Mefin factory that used to have thousands of workers but only had 500 at the moment, it was rumored that it would close soon so the ones left were depressed. It was hard to make this not appear as a bad joke. But due to this tensed situation, people actually took the time to talk to us, they were in no rush to go in, they wanted to know what was happening, what was in store for them.

The second project involved Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, we wanted to put their banner with “Long live capitalism!” on the Băneasa bridge – this was during a time when people would sit for hours in their cars at the outskirts of town. We did not get permission to display it – I now regret that we didn’t take a picture of it, at least. Back then I thought it would work only if it were visible for a few days, if it was seen by as many people as possible.

We also did the Café-Bar Manifesto series: we would meet in various cafes and put forward discussion themes that weren’t on the mainstream agenda. A part of those who took part in these discussions ended up founding CriticAtac shortly after. In 2008 I also started working at IDEA where there was a similar atmosphere for theoretical discussions. I wasn’t part of CriticAtac, but we ended up organizing events at tranzit together. I found it to be a group that was too dogmatic (with a few exceptions), especially when it came to art. There are some divergent opinions that I am still not over.

I think it’s time we talk about tranzit…

… a story that is still being written. We are a network of autonomous institutions as part of another network, that I thought of together with Livia Pancu, Attila Tordai, Lia Perjovschi and Matei Bejenaru (who left shortly after). We wanted to prove that if you have some resources, you have more to gain if you share them instead of competing for them. The budget for each tranzit in Romania is much more precarious than those outside Romania. In a way, we continued the practice each of us had with our independent institutions (E-cart, Vector, Protokoll), with a minimum budget for some security. I took two years for people to understand the conditions we were activating in and the rationale behind this structure that we chose for ourselves.

So we share the finances but we don’t meddle in each other’s programs; we have one tax office, we share Andi, our golden financial expert, we meet once a year. Our programs have become complementary, there was no overlapping and no arguments either because we each wanted to work in the context that is specific for each city and our budget does not permit extravagant projects. There were never any restrictions regrading the content from our financier. We have flexible programs, but a little less stability than in western institutions. For a long time, we self-exploited ourselves and did everything on our own, from the programs to the cleaning, in order to have more money for projects. And we’ve also exploited our close ones, Edi Constantin knows all about building contemporary art institutions and how much voluntary work is behind their functioning.

It seems to me like tranzit Bucharest invests a lot in the space as a resource: is it meant to become a safe space, a meeting space?

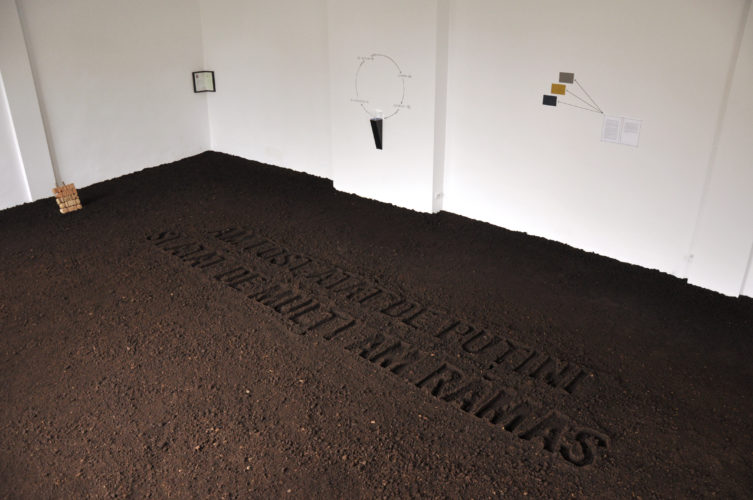

The idea of safe space was very important when we were searching for the place where tranzit is now, precisely because we were coming from work in the public space. After an ample project that we can discuss another time, The Knot, which proved to be very hard to implement in the Bucharest public space, I realized that art has its own operating spaces, and one of the goals of these spaces is to keep the art safe from any context where it can be lost, overexposed and uncertain. I wanted to have a space that can be of use for very diverse activities: political discussions or less serious talks, screenings, agriculture, a space where you can come to read a book or meet someone…

Besides, the public space is not necessarily open, you don’t have access to it by default. Carol Park, where we installed The Knot, a mobile structured, turned out to be an official park with numerous public festivities; so we had to clear the place in a few days time, to disassemble the entire structure and put it back together. At tranzit, everything is private, from the foundation that funds us to the space we rent from a landlord; nevertheless, the programs is more public that everything we did in Carol Park, I would say.

I get that tranzit is more about making resources available and less about organizing exhibitions and projects in general.

Yes, I think anyone can organize projects and the level of project organization within the various spaces in the country has risen in the last five years. At the same time, the exhibitions are important and we chose the space tranzit Bucharest is in right now first and foremost as a space for the production of exhibitions.

We’ve tried to have some constants, some elements of rhythm that allow another way of measuring time in this space. One of these constants is the project The Last Archive by Vlad Basalici: in a sea of uncertainty we know for sure that each year, on December 21st, we open the “apocalypse” exhibit. The exhibition is done by a new guest every time, we had four so far (Peter Szabo, Monotremu, Giles Eldridge, Vilmos Koter).

Another constant is the summer exhibition with an added research or art history component: the one curated by Daria Ghiu in 2013 about Romania’s participation at the Venice Biennial; Theodor Graur in 2014; the exhibition with artists that work with textiles in 2015, co-curated with Iulia Toma. After an interruption in 2016, we are now working on this year’s event that focuses on research.

What is the selection criteria for an exhibition?

There are many things. The main problem is that I am interested in many things… it’s ok this way, but on the other hand I wish I had more time for all of these interests. During the first years, I also felt a kind of responsibility for the scene because there were few spaces and some were also closing down, so the program also consisted in our answers to emergencies, not just the projects I would have wanted to do. I thought it was important to look at artists from various generations, but I am also interested in producing, like I did, for example, for Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan’s exhibition in 2013; I did a series of new works for them. There was also the 2015 Une autre cité for which the three artists, Raluca Popa, Olivia Mihălțianu and Carmen Acsinte produced new works. Or Un libro di specchi, the ad-hoc exhibition by Italian artist Valentina Vetturi as a follow-up to a one month residency in Bucharest, based on her research. We haven’t really done thematic exhibitions, except the opening one, Representations and repetitions for The University Square (2012), but we did host a few (Like a Bird, curated by Maja and Reuben Fowkes, or Repertoires of (in)discretion, curated by Tincuța Heinzel). Sometimes the exhibition was in fact generated by the space and its ambiance, like Daniela Pălimariu’s 2014 tranzitCAFÉ. Other times, the exhibition did not take place within the Bucharest tranzit space, for example the 2013 Romanian Pavilion in Venice which we produced, or the Austeria case that we co-curated with Anna Smolak in Nowy Sacz, in Poland, produced in partnership with tranzit. I have a longstanding relationship with all the artist I work with, something I wouldn’t have been able to do if I would have worked in a big museum

Surely you did not curate all the exhibitions – as far as tranzit goes, I see the curatorial gesture within the selection process, the overall program.

I think so too. I’ve also realized something else: the moment you declare something as art is the moment you draft the contract, when you describe it, you name it an installation, an object, utilitarian art… I draft these contracts with a lot of responsibility: these concepts I am defining must survive from an aesthetic and legal point of view.

With tranzit I tired to create a non-aggressive space, with no issues regarding principles or stances, but with the possibility of offering or receiving them if that is what you are seeking. We had no specific target in mind, it formed with each new project. We do have a constant public, but I never imagined I could broaden art’s audience. Instead, people enter an “art” space for a completely different activity; I am not lying to them, I don’t tell people I am offering permaculture or philosophy and give them art instead – no, I am still offering permaculture and philosophy (or at least I try), but I frame them in an art space and if people are curious, they can ask what happens in the space during the rest of the time. But I am not under the illusion that I can educate the public to understand contemporary art, nor am I interested in this. I think that mediating is a coercion instrument for the institutions: their entire program is reduced to these quantity evaluation parameters that are totally irrelevant, but this is what funding is based on.

So you turn to the artistic community…

Yes, one which I understand in a very broad sense: there are people within it who have nothing to do with art. The public is generated by the events, I do not create events for a specific public. At the same time, for me it’s important that those who facilitate art thinking survive. The safe space we were talking about earlier is, first and foremost, for these people.

If you were to wrap up tranzit, would you open another space?

It’s a tough question, overly dramatic and too unimportant at the same time. I guess we’ll see. There are no reasons to be optimistic, but this also means there is little to lose. What matters is that I be involved in a project that is at least 50% relevant for me and not just some job. tranzit did no exhaust me like my working in the public space where I am still not prepared to go back. I never had any certainty that tranzit would last longer than the usual contemporary art projects, but the stability we had so far, where we made plans every two years, obviously mattered a lot. If tranzit closes I won’t have regrets or frustrations; but if it remains open, in one way or another, I wouldn’t say we’ve exhausted all the possibilities, there is still a lot to be done.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.