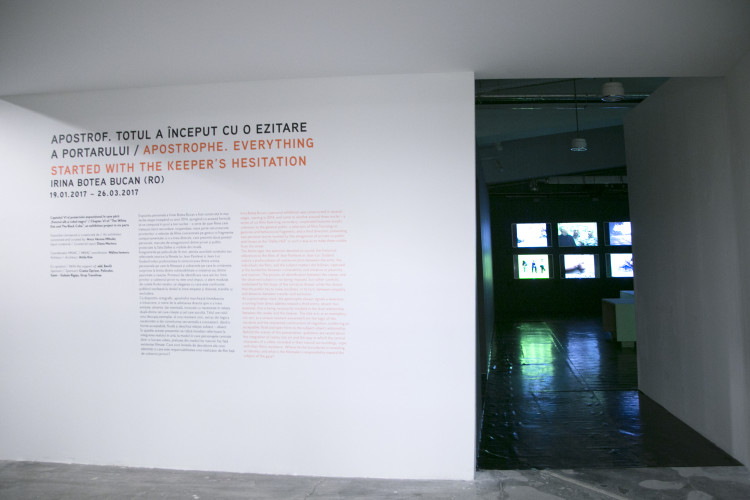

The Museum of Contemporary Art recently opened Irina Botea Bucan’s second solo show, much more ample that 2009’s A moment of citizenship which reunited two films previously screened at Jeu de Paume. The exhibition Apostrophe. Everything started with the keeper’s hesitation is a big project that brings together new works, some of them site-specific, with a consistent selection of films recently produced by the artist. Curated by Anca Mihuleț with input from Diana Marincu, the exhibition opened at MNAC shows the permanent fluidity of ideas, the complexity of simplicity and the diversity of preoccupations that define Irina Botea’s art.

Everything started with the keeper’s hesitation, this ambiguous title that made me think about the press release I read and the probability of an absurd situation caused by the MNAC guards, is an extract from a discussion between the artist and curator about football. That line made me think about the keeper who dutifully guards the absurd “law” of Kafka’s parable Before the law, which was later included in The Trial. Irina Botea Bucan sees the keeper’s hesitation in a positive light, an almost imperceptible gesture that humanizes the absurd interdiction, the open yet inaccessible space and induces the hope for “escaping the law, the possibility of finding a solution to be free of receiving orders.” The title and the architecture of the art show, which put forward a utopian layering of a football stadium and the concept of “invisible cinema”, position the viewer in a socially constructed temporality where alternative “wise-tale” histories are revealed-enacted-told-fictionalized. Convinced that the present is a consequence of history, Irina Botea is pursuing those histories that can be relevant for the present time. The hidden social critique, the kafkaesque absurd and football are some of the leitmotifs that articulate the curatorial narrative that make up Irina Botea’s MNAC exhibition.

Irina Botea works as a teacher and video artist, the two dimensions of her activity are always interconnected. She teaches her students in Chicago about art starting with her own practice and artistic experiences, while a didactic preoccupation is obvious when she chooses the subjects of her films. Irina puts together video narratives inspired by histories of local interest with a mythical or heroic potential that remains unknown outside a closed community, or quasi-invisible histories where she identifies a critical potential. “My political stance is a Marxist one, I was very influenced by the Frankfurt school of thought” said Irina in an interview with Igor Mocanu, narrowing her path down to a quote from Walter Benjamin’s writing: “a political tendency is necessary, but not sufficient.” Irina Botea Bucan’s artistic approach ca be seen as an incubator in which artistic and anthropological research become aesthetic, political, critical creation. In the text The author as a producer Walter Benjamin raises the very debated issue of the relationship between political art and the formal quality of the work, stating that it is essential for the art piece that puts forward a correct political discourse to adhere to the appropriate standards and rigours of the artistic community.

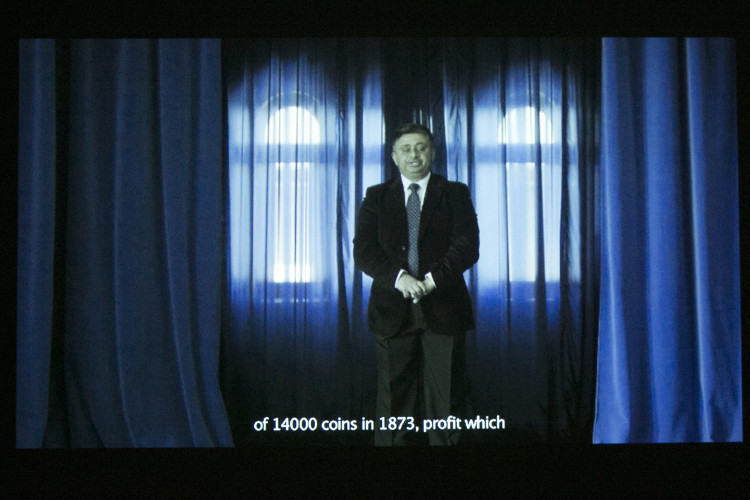

Political micro-narratives are small truths “put-into-art”, video-performances, films that mix various cinematographic techniques of theater and choreography with theoretical-artistic research, the appropriation of classical artistic language (Godard, Jean Painlevé) and, of course, the intuitive free experimentation. In the invisible cinema-stadium, seemingly random stories unfold, illustrating various situations, histories or narratives that interested Irina Botea at a certain time. For example in Budapest, with the help of Jon Dean, she picks up the story of the Fernec bar in which the son of a football player who made it in the Book of Records starts the process of museification for his father. The artist captures the bar’s inventory with the interest and attention of a museum curator studying an artefact. This museum-bar, dynamic and filled with stories, is a subtle critique aimed at the museum institution which is often stuck in the much discussed state of “artwork graveyard”. The museification of football reaches the utopian memory of sport for pleasure – art for art, outside the problematic economical transactions and relationships that now define the international sport scene.

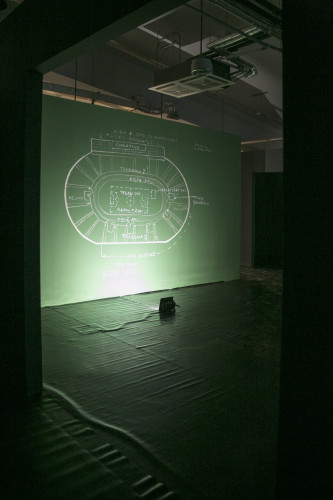

Another institutional critique hidden via football is the over-sized sketch of a stadium near the art show entry. The sketch represents a plan of the Republica stadium drawn from the memory of the artist’s father, Vasile Bucan, and blown up for the green wall in the museum. The insert reminds one of the patrimony losses as a consequence of the discharges in order to make room for the future construction of The People’s Palace/ The Parliament. The stadium, projected by Horia Creangă and Marcel Iancu during the interwar period, was rebuild after the damage produced by a fire during the second world war and, according to Dinu C. Giurăscu, hosted the first communist reunion in Romania. It was torn down in 1980 with the aid of army controlled bombing and its remains became part of the People’s Palace as the parking lot for The Chamber of Deputies. Strategically placed in the current political context of MNAC, whose location is disputed by numerous artists and specialists, the stadium sketch reminds one of the entire traumatic history of the megalomaniac Ceaușescu construction on top of the ruins of a neighborhood the size of a provincial town, stampede by bulldozers.

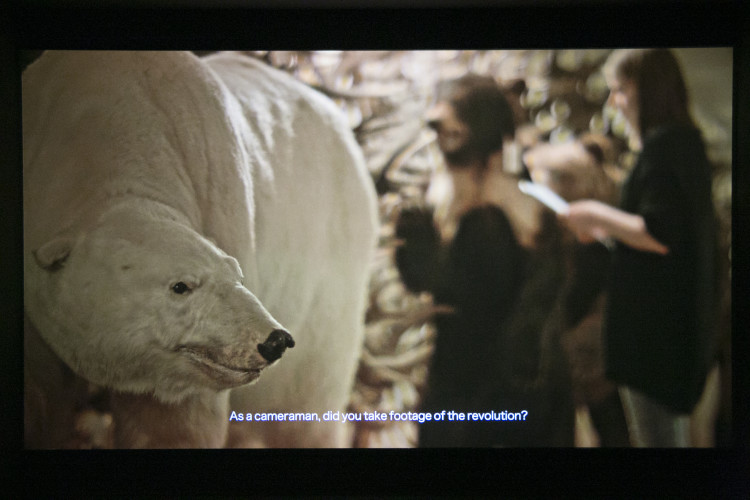

This detective work that reveals unknown histories, whose story can acquire new meaning through the understanding of contemporary man, is how Irina reveals her activist side. The story of the Teodor Diamant’s 1835 utopian community in Scăieni – The Phalanstery or the picturesque incursions of the Iulia Haşdeu Castle in Câmpina, the Nicolae Bălcescu memorial also in Câmpina and Storck Museum in Bucharest, the latter produced with Nicu Ilfoveanu’s help, represent the artist’s reflection on national history, identity myths and the whole Romanian socio-political context. She reflects with the same profoundness on a crucial moment in Hungarian history by documenting the activity of the Hungarian photo-reporter who photographed the 1956 Hungarian Revolution and an African safari for rebuilding the Budapest natural science museum, which was destroyed during the revolution, in the film Rock. Paper. Skin.

As a traveler full of inspiration, Irina Botea lingers on a story mostly fascinating in a purely subjective logic where she observes, extracts and denounces a myth, a cliche or an idea that does not correspond to the profoundly human values she supports. Irina Botea is searching for individual humanity and operates with subtle political references; her critical discourse is discernible through occasional hermetic analogies. Every work has many successive narratives that are parallel or derivative of each other, pushing each other’s political or aesthetic buttons. The exhibition Everything started with the keeper’s hesitation is a journey among information that contradicts, mocks or humorously sheds light on the current system’s rules.

Irina Botea Bucan, Apostrophe. Evereything started with the keeper’s hesitation is at MNAC Bucharest between 19 January – 26 March 2017. An exhibition conceived and curated by Anca Verona Mihuleţ. Curatorial input: Diana Marincu.

POSTED BY

Valentina Iancu

Valentina Iancu (b. 1985) is a writer with studies in art history and image theory. Her practice is hybrid, research-based, divided between editorial, educational, curatorial or management activities ...

Comments are closed here.