It happened to me first in Berlin. It was my first time in the city and I was oozing with anticipation. Nothing was slightly indicative of what was about to happen. I was in a more than charming company with a carefully detailed plan and I was convinced overall that the outcome of my trip would be tremendous. We were soberly walking along some angsty, half lit alleys, the kind you strangely enjoy walking on, while looking at the same time behind your shoulders. And then abruptly a set of questions creeped at the back of my head out of nowhere: “Why are you here? What are you doing here? And who are you in the first place?” It was not a fleeting moment of amnesia. It was a feeling so overwhelming it made me feel dizzy. Empty air came in and out without a refreshing reassurance that I am still there, as the white noise of a suddenly beat-less city inundated my ears with confusion. As I was hanging there with my memory suspended and trying to cling to something, like a substantial thought that would give me a definitive idea of who I was, suddenly my plans for future vitrified themselves like leaves under a frozen lake.

I tried to repeat to myself that I was where I was supposed to be and that, in the end, it is my right to be here, but these were almost mechanical thoughts towards which I could find no attachment. I needed to form a sense of self – and fast – as I even forgot where I should head back to and became solely dependent on my folks. Some people I turned to later in order to make sense of that moment have told me that, well, you were in a new place, everything was exciting and it was understandable to get lost. Yes, true, I admitted, but how about those later times when I was tried out by the same disorientation with places that I knew too well and still they presented themselves to me with a sense of eerie – despite rationally knowing that I have been there before. Psychologists attribute this experience of jamais vu to high levels of stress and anxiety, but if someone found solace in an explanation like that they account for the lucky ones. Forgetting something can be achieved with a simple exercise: that of repeating something over and over or writing it down until it becomes so estranged to your own mind.

Now, as I have to acknowledge the fact that I might have gotten myself in a bit of a confessional trap with this small anecdote of my life and since it is too late to pull myself out of it, I will just add that I felt a bit reassured when I saw that this seemed to happen, on a larger scale, to a bigger entity, like, say, a collective. When I arrived in Warsaw, two major exhibitions in two of the most important centers of modern and contemporary art seemed to be grinding over the same questions. The first one, at Zamek Ujadowski Center of Contemporary Art titled Late Polishness – Forms of national identity after 1989 tried to recuperate three decades of Polish art over the background of the historical events that have punctuated them. In other words, it tried to map an identity for contemporary art through a massive show of more than a hundred works by artists that supposedly shaped a site of identification. Polishness was conceptualized as a lived ‘form’ rather than a layered vessel of national heritage out of which content material would embrace different individual treatments. While not lacking in irony and self-examination and imbued with ‘postcolonial theory’ that functioned as a shielded coating in theory, the exhibition seemed at times inconsistent with its ‘higher stakes’: “it will be possible to view Polishness from very different, individual perspectives; consequently, we shall see the complexity of the phenomenon of national identity considered as a political issue, but also as one that is existential, personal, mythological, and even purely aesthetic ”. For once: Polishness or any other imagined community is not a real thing unless one really wants to invest in such a superstition. Complexity is relative and dependent on the same investment previously mentioned. As for ‘purely aesthetic’ Polishness – …this statement only asks for trouble.

Curiously enough, the inaugural room hosted the works of Stanisław Szukalski (1893-1987), the founder of the artistic movement Tribe of the Horned Heart who, returned from the U.S, tried to envision a different ‘folklore’ for Poland, one imbued with Neo-Pagan imagianarium and techno-fantasmagoria, in light of modernity’s accelerated rhythms of existence. Szukalski was the incarnation of paradox – upholding antifascist views, he is famous for a caricature statue of Mussolini, titled Remussolini, while being an anti-Semite at the same time. Failing to share his vision with the establishment of the time, he returned to the U.S., where he had fallen in oblivion up until Leo DiCaprio dedicated a retrospective to his works after he died.

Of course one cannot help to wonder: but why now? Why – except for the current political climate –a notion of Polishness needs to be addressed? It was a reassuring thing that no ideological complicity with the right wing government seemed to permeate the exhibition. At most, it displayed a clever way to obtain the funds it needed, without discomforting the money well. Eastern Europe is pretty much acing this game. It could be said that there is something of a tradition in this.

People are hoarders of symbols or events that they felt have been shared in equal measure (and with the same risks) by everyone. They fill their lives with stuff they don’t feel ready to let go. Letting go is indeed a hard task especially when you have a city like Warsaw wounded (and divided) by its remote and recent events. One work in the exhibition read almost ominously: “I wanted to cut myself off from the past and instead I cut myself”. That might happen if you are not careful enough with the blade. But a true detachment from the past is possible as troubles and urgencies are no longer ‘situated’ in dispersed loci of identification, but are threatening us all as a species. Maybe the world has no patience for a project like Late Polishness especially if one looks at recent international unfolding of events or indeed the increasingly inhospitable landscape itself. If before a space was a fixed ground onto which a nation could project its own set of values, affects and rationalizations, now the Earth seems a great deal more shaky, cracked, cranny and ready to lump us all.

If the exhibition took the recent ‘Polish’ past as a melting pot so as to create some sort of woke Polishness, it might have missed its target by a long run. If the Polish are tried out by the same dissociative disorder that I can completely relate to, maybe looking towards the past and finding some sense of togetherness in distress is not an entirely bad idea. It might not be effective but it is a way of coping after all.

Stach’s exhibition received mixed reviews and some were completely unforgiving of its vagueness and out-of-datedness. The Polish young scene, in particular, was so fed up and blazé that we could barely start a dialogue around it without a sigh of exasperation from their part. And, of course, one understands such impatience with what they perceived as another way of further provincializing the art scene. If there was no complicity with what the government would like art to look like and comprise in its discourse, then there was, as sure as hell, a whole lot of compromise. The ‘Polish soul and sensibility’, an un-examined victimization and a pervading sense of martyrdom that characterize most right wing movements today find their force into some very real and traumatic events in Polish history: the Warsaw uprising, the Smolensk plane crash, etc. It is easy to co-opt these events into resentful agendas and maybe the necessity that the exhibition felt the need to fill in was precisely this: taking back the trauma and re-wiring it in more holistic ways. Stach has led us to endless chambers (like I said, the exhibition was enormous and needed a whole day to be covered in its entirety), therefore I cannot but mention randomly what I have seen: works depicting the LGBT struggle (gay activism, gay Neo-Paganism or Neo-Catholic movements), Polish naive or rural art, masters of the 20th century, works depicting rural to urban picaresque saga (indenturedness, as in Romania, lasted until the end of the 19th century), ironic works targeted at Poland’s colonial aspirations (they tried unsuccesfully to colonize Madagascar), recent strikes and protests, homophobia, conversion to neoliberalism after the fall of communism, etc. All these were treated without nostalgic outpores of melancholia, but at the same time there was no unitary vision to take out of it. If one does not want to affiliate these things to a ‘national’ psyche, nor to a nostalgic recuperation, then what was overall stake of it? If you look at the curatorial tex,t you find nothing more than an outdated critical vocabulary: “The implementation of the project Late Polishness required the confrontation of notions, which have been engrained into past generations, regarding the essence of Polishness with such ideas, forces and processes as neoliberal capitalism, the transition from an industrial economy to one based on knowledge, the postcolonial condition, emancipatory discourses of minorities, the new dynamics of the flow of information related to the development of cyberspace, multiculturalism, and the global perspective. Late Polishness is a sense of national belonging, experienced in an era defined by the prefix post: postmodernism, postcolonialism, postindustrializm.”

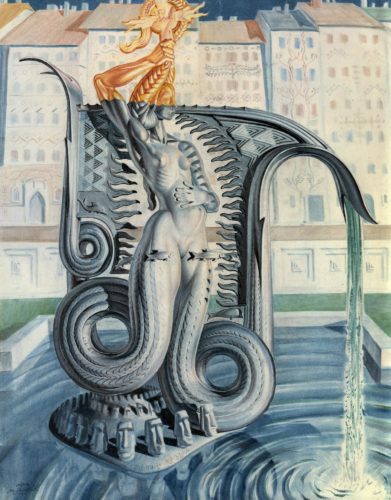

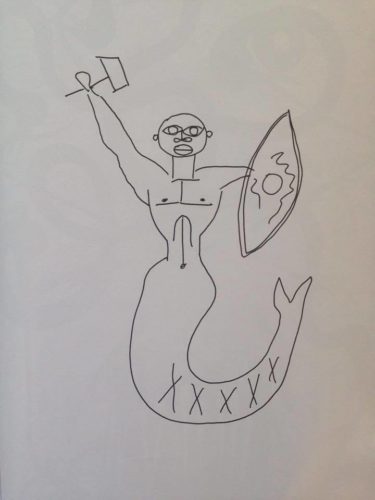

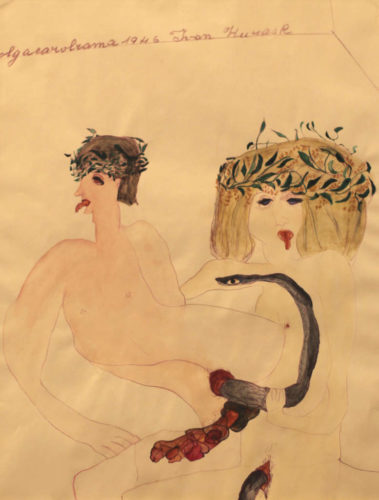

The other exhibition at MoMA, titled The Beguiling Syren is Thy Crest, also dealt with transmutations of ‘national’ archetypes, in this case that of the mermaid as patron of Warsaw. It took as point of departure a poem by a Polish romantic poet, Cyprian Kamil Norwid, who envisioned sirens as equally dangerous and fascinating creatures, an ambivalent coupling of good and evil, a recurrent trope in romantic literature and art. If the exhibition at Ujadowski center traced the formal transformations of Polishness, the one at MoMA constituted itself, on one hand, as an art historical display of the progression of the myth throughout the decades (with an emphasis on late Romantic, Symbolist or modernist reverberations of the mermaid figure), on the other as a metaphor for possible radical openings. Thus queer re-envisionings of the myth showed up in Wolfgang Tillmans photograph Lutz, Alex, Suzanne & Christoph on the Beach or the sculpture Him by Danish duet Elmgreen & Dragset, which depicts the Copenhagen Little Mermaid as a man.

Spinster by Liz Craft hinted towards the ecological decay faced in our Anthropocenic times. Deathdrop by Berlin Biennale darling Anne Uddenberg depicted a mermaid in a twisted transhumanist dystopian form while extracts from Agnieszka Smoczyńska’s Sundance nominated film The Lure explored fringy, dangerous sexuality of young women.

From the talks I had with Natalia Sielewicz and Stach Szablowski, the curators of the exhibitions in questions, I took that both were cornering the same premise: that there is this rich symbolic regime ( be it ‘national’ imagery, landscape, common history, a common set of values or set of belongings codified in symbols) that have been unfaithfully hijacked and misused by the so called patriotic, nationalistic and far right entities. Although derided, put under forks and knives by post-structuralist critique, symbols are stuff towards which people still invest a great deal of attachment. For Natalia, the hybrid creature of a siren (the miscegenation of a fish or a bird and a human) establishes an ultimately unstable, unreliable and queer functional tool in proposing alternate narratives to the ones already consecrated by Polish history or art history.

It is also true, I would add, that the symbolic order encourages prosumerist behaviours, simplifying complexities and making symbols readily available and digestible for the masses* (although I swore myself I would keep a distance from such concepts). Semiotic capital with its never ending manufacturing of dreams and desires works like that. And it works pretty well and dandy since it is not boring as the pietist alternatives still advanced by some sections of the left. It mobilizes the libidinal, the protean potential of all things animate or inanimate, of capital hybrids and their protean re-appropriations work as fuels for its multifarious forms. To assume that the other side is less ready or flexible in recycling symbolic imagery constitutes a grave underestimation.

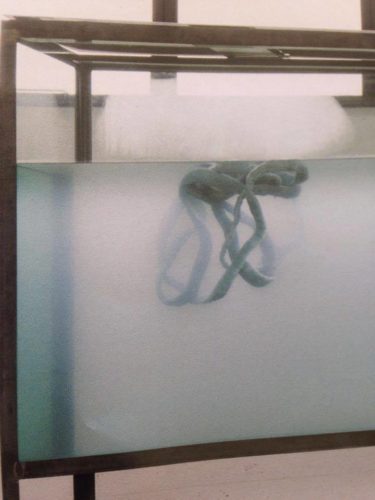

In both exhibitions Polishness – be it in the force of its historical grounding, or the art historical condensation into the myth of the siren – functioned as the great cipher, the communal dojo trying to get out of established formal or discursive formations. The exhibition at MoMA captured this struggle perfectly: on one hand our need and pleasure of fabricating stories, making sense of a communal sense of belonging using a story, legend etc. and, on the other, a need to subvert this need by trying to escape our limited, anthropomorphic propensities. Above all we love and cherish our own narcissistic complexifications – oedipal mythology being one of them –, a side of the exhibition that I assume was much appreciated by the general public. However, there were works that veered toward non-anthropocentric ways of inhabiting the mermaid’s myth. For example, the 1995 installation Portrait of things by Belgian artist Edith Dekyndt exhibits a piece of cloth submerged into an aquarium, toying with the idea of a non-human alluring mermaid-matter, indifferent to our agonizing scrutiny. As Karen Barad would put it, in Dekyndt’s work: “Matter is not little bits of nature, or a blank slate, surface, or site passively awaiting signification; nor is it an uncontested ground”. The lulling of the strange, forbidden hybridity is not, in this case, explored as an oedipal trait – as in Ulysess’ or Picasso’s orientalized siren – although this treatment of the myth did find its way within the exhibition, but only as an anecdotal evidence of Picasso’s relationship with Warsaw and his decision to sketch a heavily Africanized version of it on the walls of an apartment complex. The exhibiton also included non-European artists such as Ming Wong, whose videos made quite unveiled references to the queerness of the mermaid motive. Overall the exhibition at MoMA sweated in constructing new ways of radical imagination – in line, of course, with speculative materialism, queerness, anthropocentric imagination, transhumanism etc. While transmutations, decompositions and alternatives to a collective imagination (in case someone refrains from calling it a superstition) are already occupying conventional loci in contemporary art, it is still interesting, especially in the age of Kek and Sanders, how does the symbolic translate within social movements. While pointing towards a plain different from the immediate perceptible reality, when situated within a frame, it is necessary to point from somewhere, from a particular situated imagining. Perhaps only in this context one can grow more tolerant of anything remotely close to something like Polishness. Social and historically embedded imagination, as Armin Medosch reminds us, could work as a “composite of our capacities to affect and be affected by the world, to develop movements toward new forms of autonomous sociality and collective self-determination”.

Elsewhere, in other parts of town, all the fuss went to the centenary of the avant-garde and, as we know from our own Romanian treatment of DADA, this event was not sidestepped by gaucherie, embarrassment and disappointment. Of course there were the usual somes who reveled in their country’s contribution to the avant-garde, which is always regarded as part of a proud national heritage. With some notable exceptions (such as the DADA 100 Poetry without verse), DADA Year was similarly “celebrated” in Romania with unnecessarily officious gatherings, stiff and yawning faces and overall lack of inventiveness.

While Warsaw ‘big players’ were concerned with national identity, national symbols and the historicization and periodization of the avant-garde, the less rated private owned formations were much more keen in going their own way. I had the chance to visit an apartment gallery (and it is so refreshing to see them mushrooming everywhere) ran by kamil#2, which hosted the exhibition Xenoselves. kamil#2 told me about the struggles and importance of keeping his gallery alive and the acute lack of spaces where young artists can exhibit their works. Other privately owned galleries seem sometimes forced to maintain a commercial side while trying to keep a balance and promote new, visionary ideas. As in Bucharest, survival is a challenging game where you need to play smart if you don’t want to be swallowed by bigger fish in town. Like in Krakow, Bytom or Katowice, there are glimpses of a new scene growing away from mainstream institutions, avoiding shabbiness and pedantry while maintaining a certain level of independence. In all cases, as in Bucharest, young initiatives usually stay away from big ‘infrastructures’. A whole lot of skepticism towards them is yet to unfold into more. Talking to a Belarusean young curator, we agreed that in both our countries there seem to be two art worlds running parallel to each other, never intersecting, nor willing to. Institutional critique has been internalized by the young scene up to a point that there are no possibilities of reconciliation. However, in Warsaw the art scene seems to stand on more middling grounds and there are possibilities of reconciliation preoccupying them maybe more than in other places.

While major cuts in government funding are becoming somewhat of a predictable refrain in the East as well as in more ‘thriving’ economies, it is engaging to see how precariousness does not entirely ruin ingenuity and private initiative. That is, it is swaggering when it is not a bit sad.

Some first hand conclusions that I withdrew from my residency in Warsaw would be that, as I have predicted already, the Warsaw art scene looks more westernized than the Romanian art scene, not least because of its proximity with Berlin and other art scenes, plus the underlying art infrastructure is more bidding than its Romanian counterpart.

And if I were to close in the same confessional note that I began this article, I would just add that in Warsaw I did not feel the floor fleeting from below my feet. It felt both like a déjà-vu and a jamais vu. This time I was exactly where I was supposed to be and I would take the opportunity to thank and feel grateful for the friendships and collaborations that I have established there.

Georgiana’s residency in Poland was made possible with the generous support of AFCN, ICR Warsaw and the Polish Institute in Bucharest.

POSTED BY

Georgiana Cojocaru

Georgiana Cojocaru is an art writer, curator and editor living and working in Bucharest. At the moment, her research practice focuses on generic aesthetics, poetry in the Anthropocene and fictionalisa...

Comments are closed here.