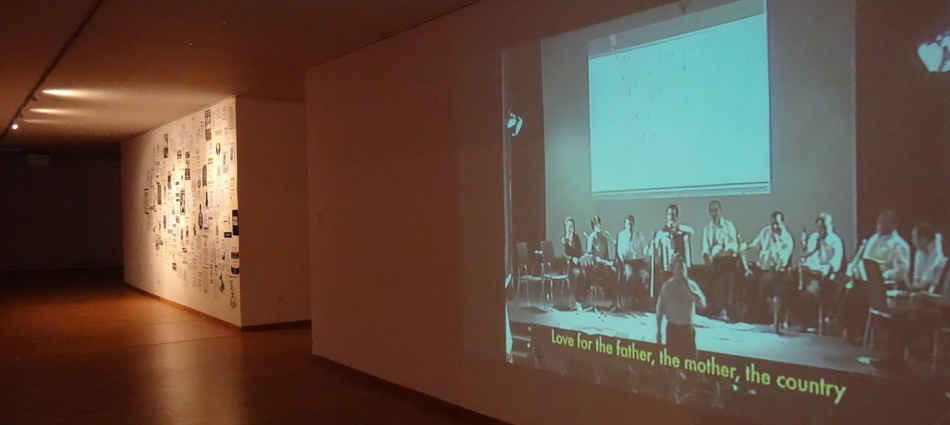

That’s exactly how you feel when you enter the art show on the 3rd floor of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest. From every corner, every wall, someone is talking to you, is gesturing to you, is trying to get your attention to listen. Tens of people want to tell you their stories – most of the time in the made-up English of world travelers or in the language of the international poor. The space is filled with signs, posters, each with their own requests, advice, announcements and frustrations. Even the box that spits out sunflower seeds is noisy and won’t leave you alone. You feel upset, criticized, watched by big eyes that stare at you hidden or in plain sight, eyes filled with hope, or irony, or simply curiosity coming from someone who isn’t from around here.

In fact, no one is from around here and everyone – in the designated space of the work they are a part of – is measuring everyone. They’re all “Romanians” because, for a few years now, this is what the standard immigrant is known as, this is what the “others” decided. They’re all Romanians and they’re all foreigners, just like in any other big city, where no one is at home anymore. This exhibition is a perfect microcosm, a city within a city. The unfriendly space of the museum, where layers of history await to be unearthed or purposefully forgotten and covered with something that finally makes sense – it is the perfect setting even though no one looked for it. It is an ironic coincidence – like many others in this colorful and perfectly coherent exhibition which presents the condition of the immigrant by allowing artists to speak from their own experiences.

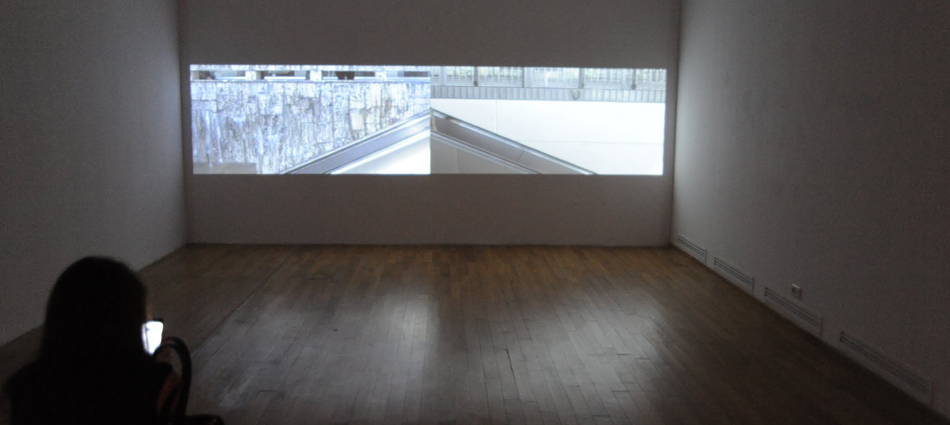

No matter where you enter the room, you’re bound to hit something that speaks to you. I prefer taking the service elevator and being greeted by – irony – two rows of people that keep bumping into each other on the escalator in two videos – one showing the metro in Bucharest and the other in Berlin – edited to mirror each other by Xandra Popescu and Larisa Crunțeanu. The background noise/music gives me goosebumps and when I look around, all the people in the videos become menacing; zombies suddenly appear floating from one wall to another. Just like in the video, the bumps are superficial, none of the protagonists are aware of them. This sets a tragic tone.

Even if you enter the room from the opposite corner, near Simion Cernica’s series of photos, “I'(m) here to help America”, the tone isn’t any cheerful. Sure, you can laugh, but you’re not sure with whom or who you’re laughing at. The artist, an immigrant in the USA for 4 years, sets a journey through common places in California, where he takes pictures of himself holding a sign that first says “I am here alone” or “I am invisible” but then it turns to “America is sick” and “I am here to help America”. Is the anonymous immigrant deluding himself or is this the realist conclusion about America as the new or perhaps eternal country for lost people? At the opening of the show, one of the signs that was exhibited – the one that said “I am invisible” – was stolen by someone who clearly understood the immigrant’s tactic in the Land of Opportunity (there is still the question of whether it speaks about the USA or about Romania, but the confusion is more important than knowing).

There are other works that present tactics for immigrants and some of them are very funny, like Ciprian Homorodean’s posters in which he is looking for work in Spain, or the thief’s manual done by the same artist. On the other hand, Ioana Cojocariu’s video, in which three women teach the artist how to beg in the street, how to take a beating from policemen, how to sit in the child yoga pose, is the harshest work in the entire exhibition. It is perfectly done and it has a clear, direct beauty to it. This works sends chills down your spine through the honesty with which the three women do their job, but also by juxtaposing three extreme ways of distorting one’s body. The child pose is perfect when begging in the street, you don’t have to show your hands or eyes to the passers, it is useful when protecting yourself from policemen and it is also relaxing. It is obvious that, neither as doer of the task or as a viewer, you can’t mistake any of the three situations. But it is possible that you can force your own perception so that you naturally operate this confusion in order to protect yourself either from physical pain or from the responsibility of the free man. The abstract body, the body in the screen, they protect you from reality and this continues in a perfect loop. On the wall facing this video, one can see Tatiana Fiodorova’s raffia bags that are decorated with images of immigrant communities and texts with tragic conclusions about being an outsider/exploited – they seem to make up the cover for Ioana Cojocariu’s work. In both cases we have young women, the bottom of the food chain, that struggle to survive extreme conditions. I wonder if the fact the artists are women has anything to do with the gloomy view on the immigrant’s condition; perhaps, as a man, you set out to conquer the world, but as a woman, your goal is clear – you set out to work, you raise money and you come back home.

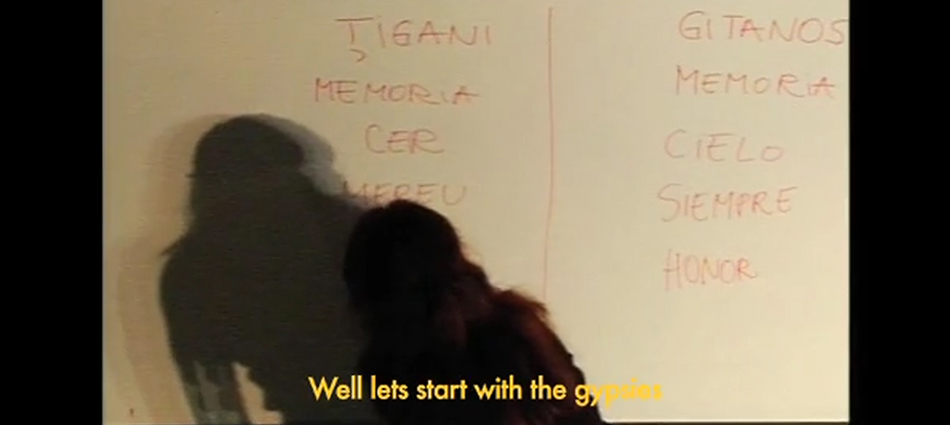

So there is a general tendency within the exhibition – and this is where I see the curatorial touch – to view the immigrant’s condition as a career. This obviously speaks to me, everything I see, I see it through the eyes of the immigrant that came back home with a plan. And it is clear that the group of curators, the duo Monotremu and the two artists behind the Magma space, shares this vision. Once you come back home, it’s in your blood, you can play with it and create art with the smallest of gestures. The smart thing behind every work is the acceptance – of the conclusion or of the hierarchy. This is how art is created by simply displacing the lines. The meaning of each work becomes intimate, as an inside joke for everyone who was – and remained – an immigrant. Irina Botea’s video, where a Romanian and a Spanish orchestra simultaneously write a common hymn, is the celebratory version of the immigrant’s route; they help each other, they bump heads, they overlap each other, they argue but the end result reminds you of home, or gives you a good vibe in any case.

The most important aspect is that this exhibition has a real statement that becomes clear with works that speak for themselves and with the works being arranged in a coherent way. I appreciate each individual work as well as the way an art show comes together and becomes much more than just a sum of art works. If I were to exemplify the notion of political art, “Never alone” would be an obvious choice.

This also means that all immigrants found their voice and that someone is listening. Even if it is about the individual hardship or the condition of the nowhere man in which we all find ourselves due to the aggressiveness of the contemporary life style, the story reaches you quickly and you instantly identify with it. While touring the exhibition, you slowly find yourself at home, in the annoying, over-friendly and forever complaining community of Romanian immigrants. But then you go out in a nostalgic mood and pass by Csiki Csaba and Tibor Karoly Liţiu’s installations – and what stays with you is the real state of the immigrant, forever removed from the object of their desire which is, in one way or another, home.

Never Alone is between 4 June – 1 November 2015 at the National Museum of Contemporary Art (MNAC) in Bucharest

Artists: Irina Botea, Simion Cernica, Ioana Cojocariu, Csiki Csaba, Tatiana Fiodorova, Ciprian Homorodean, István László, Tibor Karoly Liţiu, Xandra Popescu and Larisa Crunţeanu, Váncsa Domokos, Veres Szabolcs

Curators: the artistic duo MONOTREMU and the artists-curators of the project space MAGMA Contemporary Medium

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.