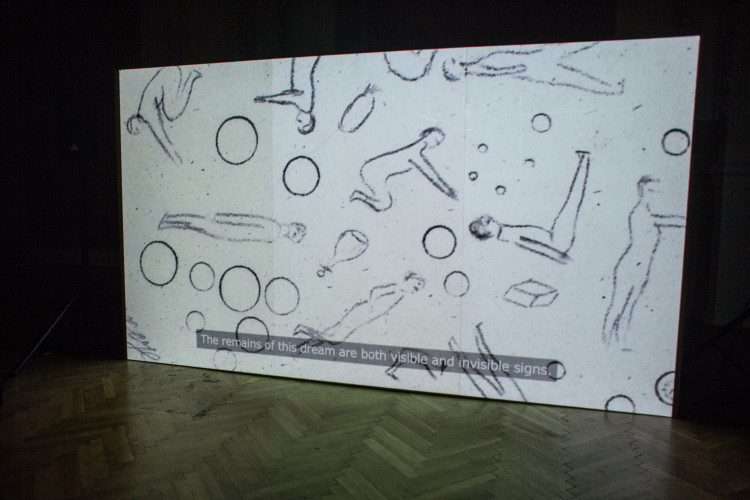

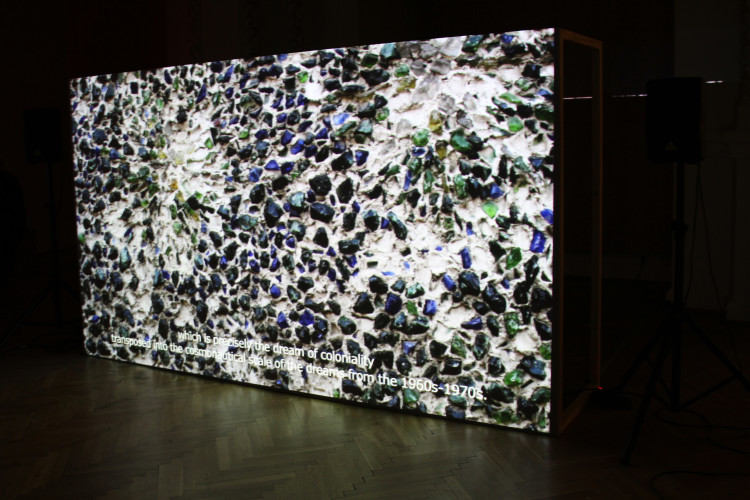

The art show that was part of Future Museum is based on the idea of utopia or what remains after utopia, whatever stays in our consciousness after waking up from a dream in which it seemed that we were all together, writing a different history.

Utopia, as seen by Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, contains all the essential elements of a historical utopia presented in the vastest forms of cultural exploration of shape, functionality and content when interacting and conditioned by a specific social context.[i] For Vătămanu & Tudor, the form and content of utopia become primordial, despite its functionality, via a conceptual break from the concrete Marxist utopia. The desire and materiality of the dream are highlighted without sacrificing or overlooking the analysis of real social relationships and their transformation in the specific context of today’s Eastern Europe. The utopian impulse is in balance with the pressure of the performative principle and the pleasure of establishment via repressive deposition. The impossibility of an ideal space society that is capable of negotiating its social shortages and overtaking the historical fatalism that links socialism and utopia does not abandon the idea of utopia, but transforms it into what Tom Moylan called a critical utopia, an example of the game between formal changes and functional ideological transformations.

Future Museum is a platform that encourages vague concepts, unclear intentions, unknown phenomena and unprecedented theories in a cult of the future and the new. Time and space are reconfigured through social changes and transitional (or transfer) moments, through a new play that centers around the form and function of the artistic process and not the functionality of the new concepts. What Future Museum wants to avoid is art becoming a commodity, art that gravitates around profitable investments. Of course, the question is: how? The answer seems simple: by constantly avoiding to confirm the everyday and the political systems, by avoiding dreamless sleeping under the blanket of powerlessness, under the control of fake dreams produced by mass media and big screen movies. But we already know from Sandor Ferenczi that the anguish dream, or what is now know as the nightmare, is the only place where deeply hidden desires truly become real, with the censorship of civilization allowing them to pass to the level of consciousness only in the guise of feelings of anxiety or disgust.[ii]

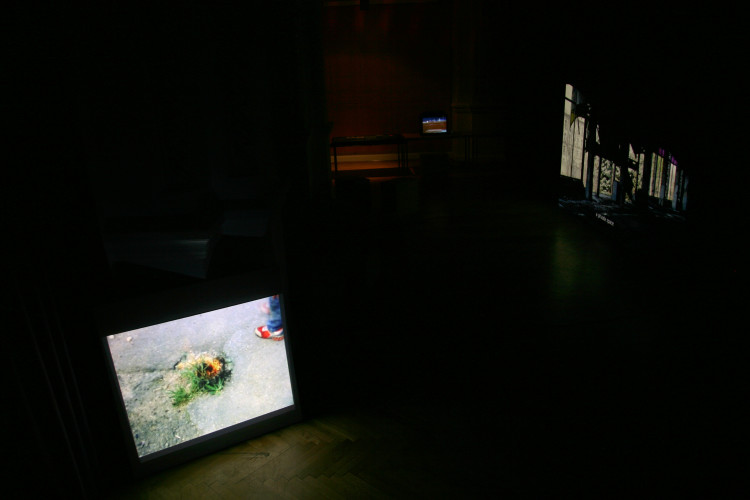

A film on a big screen mixes these ideas in an essay called Gagarin’s Tree. The exhibition space at the Czech Center has a tree-like structure of screens, the center being the Soviet astronaut’s tree. Just like an oak planted in advance, basically an interview with Ovidiu Țichindeleanu about themes such as the exploration of space, imagination and propaganda in a socialist utopia, the post-communist situation, socialist popular art, anticipation, free colonization, the movie essay is, first and foremost, an intimate portrait of the writer, evident in the moments of silence, of waiting, of thoughtful walks through the ruins of the Moldavian socialism.

The dream of conquering space in Moldova takes the form of a plowman that plows galaxies, with the intellectuals and the artists paradoxically representing the last of the peasants whose work refuses the technologies of modern age. Space is presented as a rainbow, a new dream for farmers who rewrite their history. Gagarin, the absolute astronaut, was the embodiment of this space dream, a galactic Soviet civilization. Gagarin’s tree is no ordinary tree, it is an oak, a venerated tree with a long cultural tradition, from Hercules’ bat to the crutches of the Slavic priest. As a link between the earth and the sky, the oak, just like the plow, is an easy to spot masculine symbol that can fertilize, both examples are compared to a phallus. In popular traditions, both phallic symbols dominate the earth by spiritual penetration. The plow that makes the first furrow in cosmos, an allegoric Gagarin, signifies the spiritual conversion of all nations to galactic communism.

Gagarin’s oak, planted for the first time in Tainitski park, near the Kremlin, two days after he landed in 1961, was followed by a series of oaks planted by Gagarin in the soviet republics, including Chișinău. The film crew identifies the tree from the title. The moment of the initial planting caused an entire tradition of trees planted by astronauts before leaving for space, a mandatory ceremony that has the spiritual role of leaving a tribute to the planet when leaving it, in a lot of cases with little chance of returning. The series of rituals by astronauts from the former Soviet Union contain an element of rural superstition, from the custom of urinating on the right wheel of the bus that is taking the astronaut to the ship (gesture initiated by Gagarin), to avoiding to look at the ship when it is brought to the launch pad (means bad luck).

Although Țichindeleanu positions the conquering of space as contradictory to the Mad Max post-apocalypse, regretfully mentioning that today’s post-apocalyptic vision is placed upon the ruins of past civilizations, the anticipations authors of the socialist East weren’t blindly optimistic, they massively applied warnings. The conquering of space is an urgent need, in the context of limitless harshness, with the purpose of warning everyone of the immanent danger. This way, the plowman that plows the sky can be seen as a simple warning against the disaster that is yet to come or is happening already. Anticipation artists and authors are certain that what will follow cannot be peaceful, warm, serene or general well-being. As Alexandru Mironov wrote in a collection of short stories by Romanian authors called A planet named Anticipation: “the creators of Science Fiction were the first to invent – via warnings – the atomic bomb, violent totalitarianism, mass manipulation, intergalactic wars.” However, in the same introduction, Mironov writes in 1985 about the desire for the impossible and absurd “infinite future for earthlings, a safe future”, “this undoubted and inevitable communism. Where equality will be law no. 1, where care and love for others will be written in our own genetic codes. A future which can be described in one sentence: communism is that period for humanity where there never, in no place nor in any way are children ever to die.” [iii]

The conceptual exploration of critical utopia begins with the ruins of present days, the ruined future of various historical eras and messianisms from the past. Țichindeleanu takes a step back from the ruins of Gagarin space, an abandoned youth center, the sum of all Soviet,post-communist transition and future history ruins in order to find new historic consciousness, new stories and, definitely, a new future. In his opinion, perhaps the role of ruins today, for the first time after 1989, is a positive one via the formation of a new consciousness within the order of modern age.

Writing an alternative history of the world has failed, but the memory of this attempt is still present and active whenever utopia becomes the everyday. Socialist realism, as a failed attempt to write another non-western modern age, has left deep marks just like the plowman that plows the universe in the Gagarin space.

Thomas Sankara, the creator of a regional African internationalism, did not have an equivalent in Eastern Europe and Țichindeleanu sees this lack of regional collaboration and common institutions, this absence of dreams in Eastern Sankara, as a bad influence on a modern Western imaginarium, the main local option being the link to modern age from the center. All these taken into account, the legacy of deviating from the modern image of the self and society is still present and has left marks that can have catalyst effects and still has a potential for renewal.

Getting back to the idea of utopia and its conceptual reiterating makes Gagarin’s Tree about overcoming the limits set by past theories that are no longer relevant. This time vision, the of utopia does not include a capacity of materialization, whether it’s a divine intervention or an ideal world with different social ensembles, placed in another space or in an imminent future. Rejecting the idea of universal utopia, even within the Soviet Union, and favoring a specific content of ideas are part of the main disapproval towards a utopian vision that has the power to transform or face the past. But the most rejected utopia of all, within the movie essay, is the neoconservative and neoliberal vision that dominated the western world in the 1980s and the eastern world (Moldavia included) in the 1990s, a utopian vision that expresses by default the desire of a different way of life, seen by its partisans as better and more satisfying for the individual, which contradicted the socialist way of life and well-being. On top of the socialist ruins, we are surrounded by the ruins of the neoliberal 1990s, an utopia that tragically failed, just like the plowman that plows the sky, with deep marks all around.

[i] Levitas, Ruth. The Concept of Utopia. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2010.

[ii] Ferenczi Sandor. Sexuality and psychoanalysis . Translated by Monica Medeleanu, Bucharest: Herald publishing house, 2012.

[iii] Alexandru Mironov, „Let’s speak in Earth tongue“. In Alexandru Mironov and Dan Merișca, editors, A planet named Anticipation , Iași: Junimea, 1985, 5-9.

Mona Vatamanu & Florin Tudor, What seems to be still alive is the power of that dream to bring people together and to create another history, was between 19 September – 21 October 2016 at Future Museum.

POSTED BY

Mihai Lukács

Mihai Lukacs (b. 1980) is a stage director, performer, theorist. Lukacs holds a PhD in comparative gender studies from Central European University Budapest with a thesis on the male hysteria of the m...

Comments are closed here.