I arrived at the exhibition Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory on a quiet Saturday to spend some time with Aurora Kiràly in the intimate space at Anca Poterașu Gallery, a building filled with the allure of the early caravanserai from the olden days of Bucharest. Our talk about memory, art, the importance of genre in our activities, the system’s lacunae or other theoretical ideas (and ideals) opened up more ways of seeing, reading, and analyzing the exhibition.

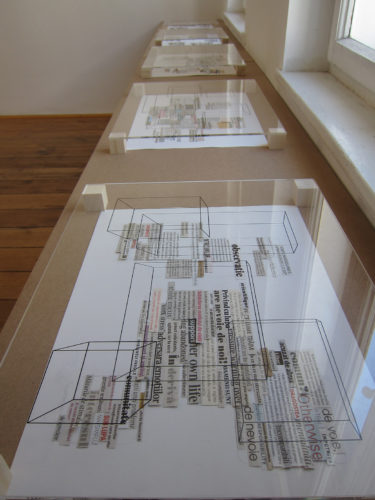

The first room includes the series Viewfinder (2014-2016) and Viewfinder mock-ups (2016-2017) of plane and solid geometrical constructions, where old photographs are integrated into new spatial and symbolic configurations. In the second room, the private photography series Melancholia (1998-2008) stand adjacent to the geometrical shapes drawn on plexiglass, framing the space with recent collages News Remix (2017) of words with nationalistic contents in the shape of newspaper cut-outs. Although different in appearance, the three projects of four series are brought together in a solo exhibition at Anca Poterașu Gallery and present some of the directions that the artist explored in the past years in which her public activity was mainly related to the curatorial and theoretical space Galeria Nouă and UNArte gallery.

The projects initiated since 1998 are reduced to a common denominator, continued and developed coherently in a uniform and complex trajectory. Aurora Kiràly combines artistic practices with theoretical, curatorial and educational practices. I will look at each of the series displayed in the project Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory in the larger context of the artist’s activities.

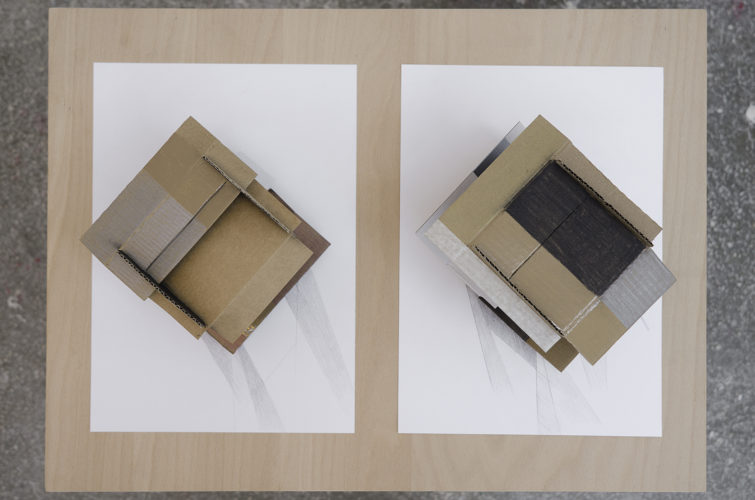

Last year, Aurora Kiràly made her presence in the Cluj art scene in her triple- hypostasis of artist, curator and teacher (which characterizes most of her professional practice) with the project Girls with ideas [Boys and paintings] opened at Lateral space at The Paintbrush Factory. In this group show, Aurora exhibited mock-ups of cameras, of cardboard manual cuts, in which she tucked prints of the photographs she took at the beginning of 2000s. These works are part of an extended series of works which propose a phenomenological approach to photography, as a recurrent method in the artist’s body of works. The visual conceptualizations depart from theoretical reflections (Barthes, Lacan, Sontag, Baldessari, Beuys etc.) articulated with the precision of an educator. With this approach, Aurora returned on the art scene as an artist, for her first solo exhibition after a long absence, a time which she dedicated to educating and promoting other creators through Cut & Paste Histories at Alert Studio. Mock-ups were created manually for the sake of the gesture and the charm of its imperfections. For this exhibition, the objects at Anca Poterașu Gallery took on an industrial perfectly touched-up shape. These cardboard cameras are related to the 3D visual representations and include a series of references and appropriations of various turning points in art history (the avant-garde, conceptual art, or constructivism). The mindful reflection on the technics of photography in Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory involuntarily leads me to compare it with the iconic technical lesson of cinematography in the avant-garde movie A Man with a Movie Camera (1929). Similarly with the creator of the Russian movie who walks with a camera in his hands and explores filming techniques (double exposure, slow-motion, gross-plan, extreme close-ups etc.), Aurora Kiràly tests and theorizes the possibilities of photography, pushing further the limits of the two-dimensional medium.

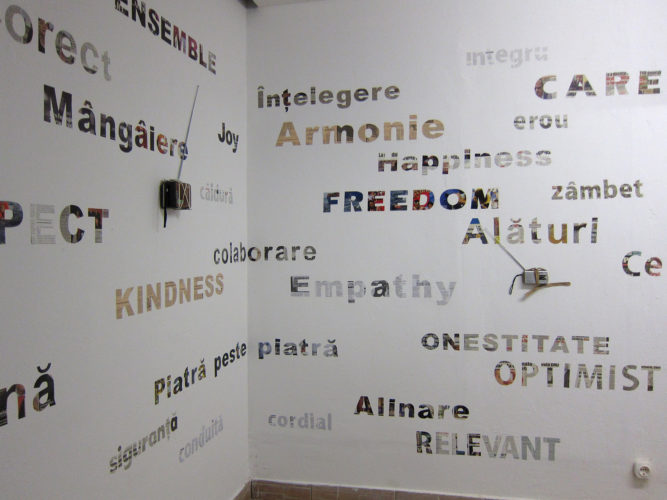

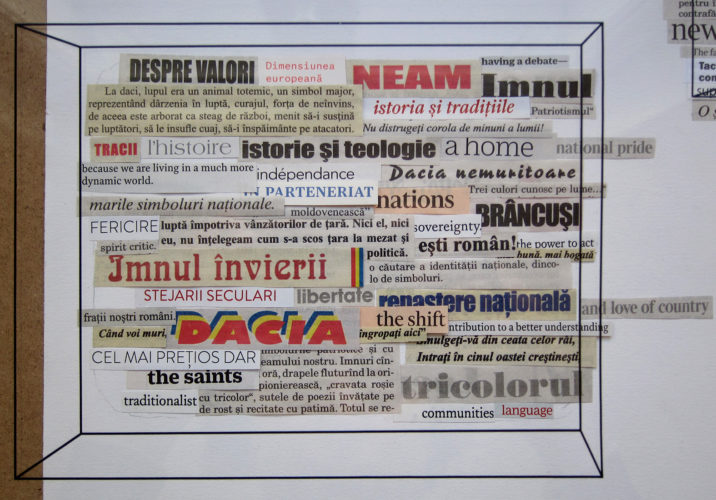

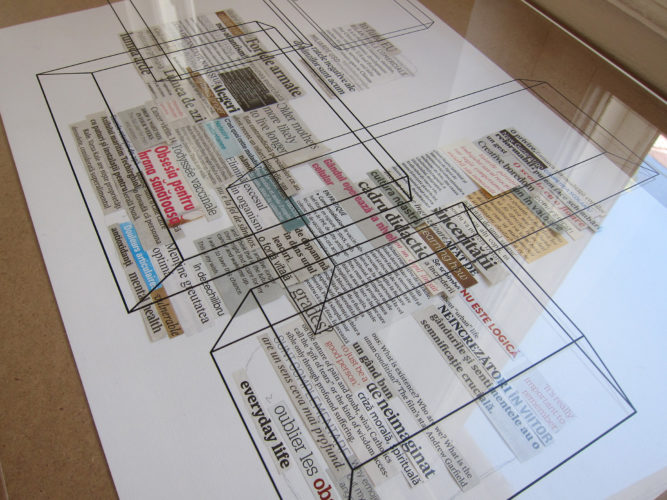

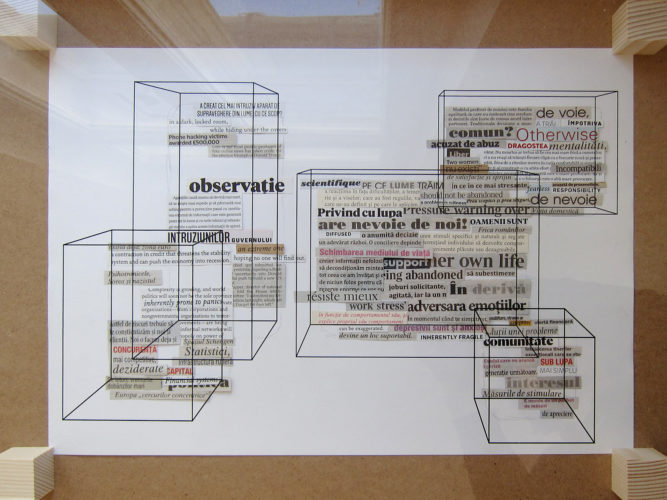

Along with the theoretical approach and the artistic reflections of the limits of the photographic medium, another constant preoccupation appears from working with visual representations of words. Within established conceptual and neo-conceptual practices, visual representations of words open up new ways of deconstructing the academic mythologies regarding art’s prospects in relation with the image. During the exhibitions last year, Reality Check at Calina contemporary art space, and a site-specific installation made for the macro-exhibition as part of a residency at Scena 9, Aurora Kiràly constructed her visual narratives by working with word formations. This research is carried on in her recent works, the New Remix series, exhibited in the solo show Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory. This visual exploration of words proposes a “dematerialization of the artistic object” (Duchamp). The collages made of newspaper cut-outs add the nationalistic obsession to other recurrent problems (generally political) found in newspapers. Aurora Kiràly proposes a critical reflection through deconstruction, emphasizing several problems in our society today, using her own personal radar to detect and select the cut-outs from newspapers. The neo-conceptual practices to (re)signify the word, politically and visually, open up various ways to reflect the semiotics in the persuasive language of the mass-media.

Walking through the gallery and looking together at the sublime series Melancholia (1998-2008), Aurora confessed, somehow intimidated, about the sensitiveness and femininity of these works, a side of herself which she poignantly felt to detach from. Listening to the recorded discussion we had in the gallery, where the statement kept running in my mind and echoed deep with my own concern for the need of a feminist perspective in art history, I began to reflect on the institutional context in which the artist works.

In 2007 Aurora Kiràly joined the university-academic field as a lecturer for the Photo-Video Department in the context of a male dominated National Arts University. However absurd it may sound for the century we live in, the women’s access in the artistic-academic realm is ridiculously normed. I even wonder if Under the tree we grew up by Veda Popovici, a work ironizing the absence of women in the Painting Department of UNAarte is still relevant, or female lecturers have been already tenured in these departments. The university was built with a male predominance which (still) generates discriminatory practices and discourses. The ladies section (founded in Bucharest in 1895 after long debates) paved the way for women to get a professional education in inferior preparatory conditions compared to the ones destined for their male peers. Shortly after, the equality proposed during the communist regime did not only erase the existent stereotypes, but it permanently confirmed the masculine authority. The National Arts University, regardless of the inevitable changes in the historical turmoil, constantly perpetuated gender inequalities. It is rather indubitable that the operations of these activities in an intellectual-rigid framework, which devalue femininity, impose a main coercion: the internalization of the masculine way of seeing. Nevertheless, for a female artist positioned in this context, since this association with the “too feminine” is always derogatory, the need for overcoming this endeavor becomes imminent.

Melancholia is a series of black and white photographs taken at the home, the studio, on holidays or residencies. They portray a visual journal of intimate moments captured spontaneously. Many self-portraits are mainly classic frames where light and shadow take the role of (de)constructing solidity. The intimacy of images is salient, we are seeing memory capsules archiving close moments (or extremely personal). The camera becomes a controlled machine, while the selections of the moments are emotionally guided by the artist, the series being thus a fragile reflection of a self-identity. “The memory, the power (of mind) to have a present that is irrefutably in the past” (Arendt), becomes the function of photography, to bring the self in the center of artistic preoccupations. Storing personal moments using photography is a practice adopted and established through resistance and courage by some of today’s iconic artists (I mention here Claude Cahun, Woodman, Jo Spence, Cindy Sherman etc). By all means, self-portraits were (and will be) a form of resistance and activism, a positive representation which builds self-esteem and the consciousness of the limits dictated by the gender manipulation in the artistic field. For the first female artists (active long before the feminist revolutions) access to nude models was forbidden, thus the portrayal of another body was a taboo. The study of one’s own body was the only accepted form of sexual education, basically the only way female artists could transgress socially and politically, and escape from the imposed constraints. Narrated in a feminist note, the self-representation of females is an essential practice to fight gender stereotyping. These soft compositions, filled with emotions and sensitivity leads to an acceptance of the feminine identity. Aurora Kiràly has always positioned herself in relation to the history of feminine art, chasing it through her own artistic practice.

Seen through the gender glasses, the exhibition Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory touches upon an essential issue, raised by Nina Arbore as a response to the patriarchal logic in which woman are forced to act: “There is no sensibility particularly feminine in arts, for the simple reason that intelligence and art have no gender. A drawing of mine, hard, edgy and solid, can be more masculine than a bouquet of lilacs next to a purple envelope made by whatever painter. A sensibility particularly feminine is not related to the gender of its creator, only to his way of being.”

The solo exhibition of Aurora Kiràly Constructed geometries. Space / time / memory is on view at Anca Poterașu Gallery between 30 March – 30 May 2017.

POSTED BY

Valentina Iancu

Valentina Iancu (b. 1985) is a writer with studies in art history and image theory. Her practice is hybrid, research-based, divided between editorial, educational, curatorial or management activities ...

2 Comments

Guys, have a serious spelling and fluency check before you publish. There is a nice tool out there called Grammarly which might help. It’s really difficult to read through the text otherwise and it makes for some ridiculous moments when even the names referenced are butchered 🙁

Ah perhaps it is a rather unfair comment? The “butchered” name was in a Romanian altered form – we do appreciate you noticing it, but one can hardly say it turned the whole text into a difficult read. Nevertheless, we are committed to producing high quality translations of otherwise complex critical texts, so we are taking your observation seriously and will do our best to publish clean texts only.