The new permanent exhibition which opened at the Pompidou Center in Paris in July 2014, called A history. Art, Architecture and Design from the 1980s to present day is a way of revisiting all of the museum’s recent collections and, at the same time, an attempt to digest the last 30 years of contemporary art. By selecting the artworks and the texts in the catalogue, Christine Macel takes on the subjectivity that comes with the role of the curator, placing herself in the continuity of a museum tradition that began in the late 70s. Looking at the works and the selected artists, it is clear that Christine Macel’s proposal is a lucid reading into the deadlock of art practice and art theory from the last 30 years, a view from the modest standing point of contemporary art. This period is known for the displacement of concepts and spectacular role reversals. We can even talk about a displacement of the notion of “art work” and “art practice” from a semantic point of view.

A history…, among the many possible histories of contemporary art, is a sketch of the landscape of international contemporary art that was built by the Center Pompidou’s collections. The singular will that gave birth to this exhibition is the wish to maintain the museum alive with a periodic review of its permanent exhibitions. The goal of this hesitant, yet exploratory march is flexibility and self-reflexivity, while avoiding to firmly and precisely positioning itself in guiding this process of constructing the landscape of contemporary art. The principle is that of a horizontal history (theorized by Piotr Piotrwoski), a thematic history that willingly mixes styles and chronologies in order to achieve an actual vision that is torn from the traditional scheme of a universal consensus that defines art. Today’s art era is that of the globalized art. It is known and practiced with the same language instruments all over the world, but it does not need to be universally accepted as is the case of the Illuminist aesthetics. The criteria for judging is liquefied and approaching a unique methodology is not a solid enough theoretical stake. As a consequence there is constant movement and turmoil because this event puts at stake more than one outlook on art.

With these two complementary products, the exhibition and the catalogue, Christine Macel displays an honest helplessness: the contemporary art phenomenon is still hard to study and its multiple crises and contradictions feed a sometimes violent debate. But its mere existence causes commotion. We could say that the catalogue studies and clarifies the exhibited works and the exhibition itself explains the theories in the catalogue. A few general hypothesis suggest that the exhibition’s circuit has been conceived as a portrait of a contemporary artist. This artist’s characteristics, even though absolutely plausible, are suffering under the pressure of the curator’s need for coherence and unity, when they are in fact extremely vague and subjective.

The first category of artists is that of the “Historical artists” (Thomas Hirschhorn, Jean-Luc Goddard, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ayşe Erkmen, Chris Marker, Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, Roman Ondãk, Mircea Cantor, Martin Parr). This selective (and very subjective) list of names suggests the fragility of this category. If Christ Marker and the Romanian couple Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor were chosen because of their works about communism in Romania, this argument is not sufficient in categorizing them as artists whose main interest is history. The common ground for the works by these artists is the fact they refer to the same event that occurred in history, more precisely in the same geographical context – Romania, but the way they approached their videos are almost opposite: Vătămanu and Tudor activate in an area of actionism and the individual participation in the course of history, while Chris Marker is criticizing an over-advertised contemporary era with irony and unjustified cynicism (Marker made a movie using footage from the trial of the Ceauşescus that is interrupted in its most important moments by western commercials for household items). It is also difficult to think of Basquiat as an artist who is interested in historical subjects. The only evidence to support this might be the fact that he is part of the emerging Afro-American movement from the 1980s. As for Martin Parr, his approach is more ethnographical than historical. His terribly anecdotal and almost kitsch photographs can be seen as witnesses to history, but not as the protagonists in producing history.

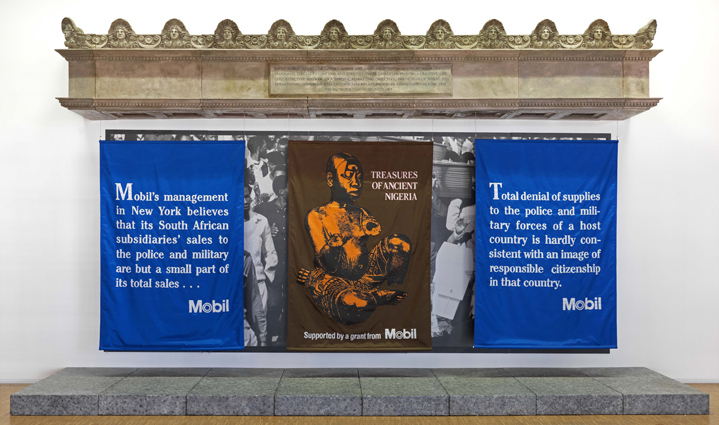

The next two sections, although kept apart, tend to fall in the same category: “The archiving artist” and “The documenting artist”. Gerhard Richter, Christian Boltanski, Kader Attia, Frédéric Brulz Bonarbé, Hassan Darsi (Le projet de la maquette, 2002-2003), Lamia Joreige (Under Writing Beiruth, 2003) are placed in the archive zone of the history-in-the-making, but the reasons why these artists are preoccupied with archiving are very different: it is obvious that Darsi and Joreige are into militancy and politics, Richter sees the aesthetic and nostalgic value of the archive, while for Boltanski and Attia it represents a generator for social dialogue and an interrogation of the value of collective memory. Categorizing Jean-Marc Bustamante, Ahmet Mater (Northern Gate, 2012), Malachi Farrel (O’Black, Atelier Clandestin, 2004-2005) as documentarists can be questionable, but it can justify the presence of artists such as Amar Kanwar (The Scene of Crime, 2011), Allan Sekula (Seventy in Seven, 1993) or Tony Oursler (9/11/2001).

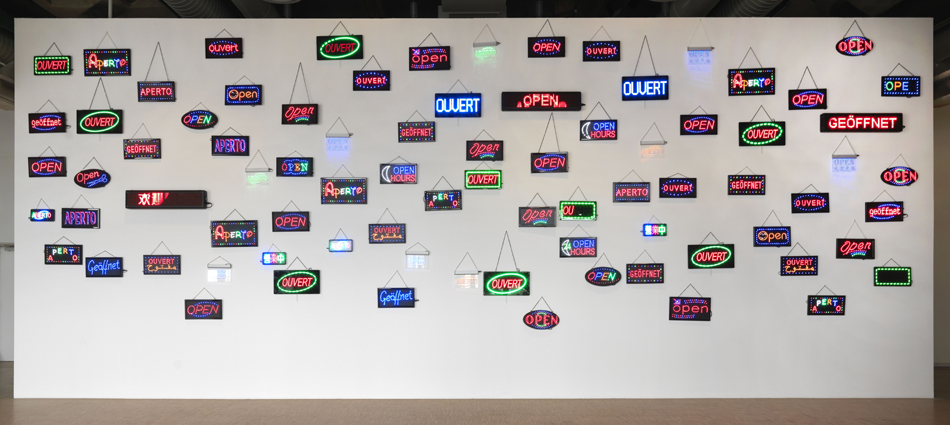

The contemporary artists cross from the big historical events over to micro-history, asking the same questions available for the bigger history: “The Artist face to face with the Object”. This section of the exhibitions wants to analyze the artist’s reactions and the types of interrogation that resulted from encountering the ordinary: Gabriel Orozco (La DS, 1993, Cutting Rings, 1995), Andreas Gursky (99 cent, 1999), Wilfredo Prieto (Avalancha, 2003), Abraham Cruzvillegas (Autoportrait aveugle très joyeux et émotionnel, pensant à un avenir radieux, 2012), Tobias Putrih (Times, 2011).

On the other side of ordinary we have the spectacular, neatly presented in the section “The Artist as Producer”, the “Traffic” generation: Maurizio Cattelan (Lullaby, 1994), Liam Gillick (Revision/22ndFloor Wall Design, 1998), Pierre Joseph (Paintballers, 1992), Rikrit Tiravanija (Untitled, Cooking corner version no.3, 2005), Carsten Höller, Tobias Rehberger, Olafur Eliasson. These artists are preoccupied with the constant dematerialization of art and its becoming a society that is only interested in events (Guy Debord, Société du spectacle, 1967), so they invest the subject of “Time” with different techniques, thus creating all sorts of participative events that investigate “unproductive time”, spare time, giving birth to works that are built on the drama of a playful and participative script.

From the spectacular to the situational (Erwin Goffman, La mise en scène de la vie quotidienne, 1973), the crossing is possible via a shift in focus with the artist concentrating on individual performative actions with a purely choreographically context. In this section we find the performance artists that came after the 1990s: Roman Singer, Roman Ondãk (Crowd, 2004), Marina Abramovic.

Another criteria that helps to define the contemporary artist is its ability to build narrations. “The Artist as a Narrator: fictions of intimacy” is a section of the exhibition that contains works with an autobiographical touch: Nan Goldin, Annette Messager, Sophie Calle, Dayanita Singh, Zineb Sedira, Mohamed Camara, Larry Clarck. It’s obvious that we have to deal with a vast majority of women in this section, which leads to a subversive observation (that is not assumed by the exhibition): the birth of sexism militancy as a constant preoccupation of the contemporary artist and his obsession with the individualistic values, with egocentrism becoming the universal focal point of his thoughts.

We discover a sort of continuation of the reflection on the relationships between individual and collective, spectator and actor in the body section: Cindy Sherman, Mike Kelley, Absalom, Dan Perjovschi, Regina Jose Galindo (Perra, 2005), Zhang Huan (Tree, 2000), Oleg Kulik (Mad Dog, 1994), Louise Bourgeois. The body (of the artist more often) is hurt, masked, or exposed to danger in many ways. The body is often considered to be the space for unfolding an event, or as a demonstrative object. The actions that fall upon it are reflections on eroticism, death, daily use, disproving the family or society’s education, or plastic surgery (Orlan).

Despite the evident torn from the old art world, by removing the classical aesthetical criteria, it is obvious that contemporary themes are just as universal as those we see in classical art. Judging by the traditional categories: portrait, composition, static nature, historical subjects, landscapes, etc. we can built new genres of contemporary art: technocratic utopias and the criticism of technocracy; militancy of all kinds – political, economic, sexist, ecologic; criticizing new medias and defending the right to expression; individualism – subjectivity; the prophet artist – the moral artist; praising the ordinary; to quote – an invention of postmodernism and a means to a new iconography that is connoted ambiguous and polyvalent by each artist/ commissioner/ critic. We are of course discussing genres, but we can no longer distinguish them using style or materiality, we can only do so via the message, because contemporary art goes beyond a simple “will of art” and rapidly heads towards “the will of power/communication”. Any technique is good enough and any style is accepted as long as the idea is strong enough. This new outlook allows us to see, with the help of the 200 artists present in the exhibition and the 400 works, that language is a reduced and less inventive tool in the contemporary world, that this battle of art has poor means of expression, but almost infinite technical means. The technique is only an instrument in contemporary art. The shape it tales is no longer expressive, but becomes a way of communicating. The contemporary artist doesn’t know how to build many things, so he tackles vast subjects under the right to express himself that has been allowed since Duchamp. The main source of inspiration is the continuous stream of events, finding the criteria to freeze frame and make an analysis. This is the real struggle of today’s creator. The resulting art has enormous accessibility and brings about a never before seen democracy, but it loses its cathartic dimensions, irony often becomes cynicism, technical inaptitude becomes assumed, art is willingly letting go of its poetic forms in favor of a cold rationalism.

All this coupled with the artist’s loss of complexity, which is dominated by analyzing artistic phenomena, results in placing the focal point of interest from the center of things to the rim. That being said, the exotic, the preoccupation with the “image of the other” and the confrontation of parallel visions are sources of inspiration for both the museum and the art market. Joaquin Barriendos Rodriguey, Mieke Bal, Miguel Hernandrey Navarro are some of the theorists that interpret this sudden turn of taste as a new form of fetishism that is in fact a much more perverse form of colonialism of ideas. Even though the artists are from outside of Europe or America, the impulse to listen to these peripheral voices comes from the western world, which leads to a procedure that is falsely democratic. The art market disloyally contributes to the cultural politics in the same way the contemporary art biennales (ever since the 50s we’ve been witnessing a concerning multiplication of these, from the oldest, like Venice 1895, Whitney 1932, Sao Paolo 1951, Documenta in Cassel 1955, to almost 200 biennales that take place all around the world) do.

After talking about art in the last 30 years, Christine Macel says, in an alarming voice, that there is a need for new criteria to criticize art. She is a follower of Benjamin Buchloh and she quotes him when he laments over: “the disappearance of the space for critique inside the museum as a central, legitimizing institution in the bourgeois public sphere and its transformation in the hands of the new mass entertainment industry. There is a necessity to initiate thought on the criteria for evaluating art and its practices, which are often replaced with judgments on ethics.”

Art, Architecture and Design from the 1980s

Curators: Christine Macel, assisted by Micha Schischke, Keith Cheng, Mathieu Vahanian

Collaborators: Clément Chéroux, Emma Lavigne, Philippe-Alain Michaud

Architecture and design commissioners: Frédéric Migayrou, Aurélien Lemonier, Cloé Pitiot

Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, ongoing since 2 July 2014

Catalogue: Une Histoire. Art, Architecture et Design des années 1980 à nos jours, Christine Macel (coord.), co-published by Centre Pompidou and Flammarion, 2014

All images: credits Centre Georges Pompidou.

POSTED BY

Petra Vlad

Petra Vlad is an art historian who worked as a curator at the Graphic Arts department in the National Museum of Art of Romania, Bucharest. She received a grant from the Ecole Normale Supérieure in Ly...

Comments are closed here.