September 1, 2018

By Valentina Iancu

Self-Fulfiling Profecy

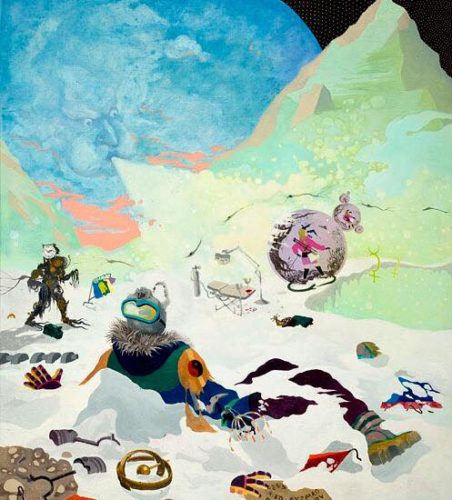

Mi Kafchin – Self-Fulfilling Prophecy, Judin Gallery, Berlin 2016 (exhibition view)

In November 2016, the Judin gallery in Berlin hosted a historic art exhibition for the queer culture: Self-Fullfiling Profecy, artist Mi Kafchin coming out as a transgender woman. Kafchin left behind a successful career built under a male name, probably all to familiar to even have to repeat it here. In Romania she had a solo show at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, the Art Museum in Cluj Napoca, the Visual Art Museum in Galaţi and some galleries in the Paintbrush Factory. In 2015, Mi moved to Berlin and soon began the transition. After that, transition-specific issues have become a leitmotiv of her art. The surrealist imagery describes the transgressive body experience in depth. I visited Mi at her Berlin workshop where she works almost nonstop and we talked about art, transition, trans-feminism, queer cycles, and many more. For a long time, I had lost hope that painting, as such a male dominated environment, might regain any cultural and political relevance. Facing the works signed by Mi Kafchin, my perspective changed. Mi uses her personal experience as a creative resource for a profoundly political art whose narrative brings into question the vulnerable reality of the trans community. Visually speaking, an entire political and theoretical universe that produces a oh, so necessary queer tension within the artistic mainstream opened up to me.

You are the first transgender artist in Romania, totally out and above all, you introduce a biographical element into your art with fantastic courage. For trans women, the beginning of the transition is an unwilling renunciation of privileges. Generally speaking, the white man is the international art market’s favorite player. I’d like to talk about gender dynamics, from your own experience.

In the environment where I lived in Romania, with professional training in sculpture, there were certain situations when I was in high school that made me always feel ashamed of what I am (and I still feel that way). Besides, I would argue that if I had been born a biological woman, I couldn’t have learned a great deal of crafts. But not because I wasn’t allowed or other extreme situations. No. In art high schools and art universities the woman is sexualized all the time with small jokes that may seem normal and harmless. In any blacksmith or carpentry workshops you could only find men, and the environment encouraged access only to a certain type of women, more masculine and harsh (who could withstand the pressure there). Professors’ sexualization has discouraged many of my female colleagues. How can one learn anything in an atmosphere where someone seems to want to have sex with you at all times? How to get metaphysical under these conditions? It has created frustrations and a sense of isolation from myself. My feminine identity was completely hidden in a body I was not comfortable with, moreover I started emphasizing my masculinity to protect myself. I am aware of the fact that there were stages in my journey from Romania, where the fact that I was born in a man’s body helped me advance: my greatest secret was also a weapon that helped me get to where I am.

You’ve managed to sum up the origin of the issues recently raised by thousands of women with the campaign “#metoo”. Education, interactions at very young ages. It sounds to me like your secret was more of a fight to survive.

This duality that no one could ever see, the woman well guarded by the very secure mask of a man’s body, helped me advance in school. The lady in me would come out only when I was home alone, when she felt safe, otherwise she lived her days sheltered by the appearance of a biological male body. There was no other way. There have been gay colleagues in art high school and university who were partially accepted, but I felt terribly ashamed. How do you come out as trans? Besides, I didn’t even know what it meant, I just thought I was a gay who loves drag.

Mi Kafchin – Self Fulfilling Profecy, 2016. ©Mi Kafchin

I totally understand because I also grew up in the same cultural obscurity where no one in the 2000’s had any clue what homosexuality was, let alone gender binary and transition. Perhaps this ignorance comes naturally in a society where the Romanian state criminalized homosexuality until 2001… I think any debate was difficult. Even nowadays, we are still so far from trans-feminism.

Trans-feminism? I am not familiar with these theories at all, not even as I live and feel myself. But trans-feminism in Romania back then? (laughs) There was nothing, no access to information. There was no internet in Galați. This was a time when I accumulated a lot of shame, fear, frustrations, but I learned a trade. I mastered several crafts so I could more easily express what I want through my art. Later on, in Berlin, I began to notice that my strangeness was not unique, that there was in fact an entire global movement, trans-feminism, etc.. The world is changing, the future will certainly be queer and trans groups are being more widely accepted and protected. Maybe the debate isn’t so difficult anymore.

Although I planed to avoid talking about the past, which could prove inconvenient, I would still like you to tell me more about your training. You seem to master various techniques and have your way with matter.

It’s ok, I can talk about my past, especially since my training process was very important to me, starting with having to work with a lot of different artists. I had the fortune of starting off quite early and was constantly encouraged. At around 2-3 years old I made a portrait of Jesus, half white, half black. Half good, half bad. I immediately began drawing classes at the Children’s Palace and won a caricature award from Popa Popas when I was around 7-8, which gave me the confidence to move forward. My teacher at the Children’s Palace, Jana Andreescu was my mentor during that time. I can still recall her scent of ink and watercolors. I pursued art further at the art high school in Galaţi where the atmosphere was quite favorable after the revolution, with many international competitions and lots of awards. In high school I learned painting, etching and sculpture. In Mugurel Vrânceanu’s studio, a professor dubbed Hephaestus who would insist on teaching all techniques as the were written in Baraschi’s manual of sculpture, I mastered iron welding, working with marble, wood, plaster, metaloplast, locksmith techniques. Basically everything written in old sculpture manuals.

Your debut was during your high school years with a solo show at The Visual Art Museum in Galaţi.

Yes, my first solo show, Insectomania, took place during high school, under Mugur Vrânceanu’s wing. It was my Brâncuși phase, with a beard, and I displayed sculptures (which totally sold out). Then came a semi-solo show with another colleague, which also took place at the Visual Art Museum. Dan Nanu, the director of the museum, was very supportive. This local mini-success made me feel loved, that my work was appreciated. So it was worth moving forward. Even though I flunked my philosophy exam at the end of high school, my self esteem grew and I already knew that I was going to make art for the rest of my life and I was very excited to pursue my art studies.

Why did you chose the University of Art in Cluj? Did it meet your expectations?

It wasn’t really a calculated move that I could explain: I left for Cluj with not much information, I didn’t even know where the University was. The admission exams for award winning students was being held separately so I was incognito until classes actually started. I remember I had very high expectations: I dreamed of monumental things that had nothing to do with the university’s reality. But it is a choice I do not regret: in Cluj, people are closer and more open, even though I wouldn’t go as far as to say they are truly inclusive. I earned a scholarship to study ceramics-glass-metal, then I switched my major. It was a very active time in my life which I totally dedicated to my work. I was involved in organizing the glass department, I even helped with building the furnaces. And I worked non-stop. During that time, I wanted to stay on as a professor at the university.

What art shows did you have during college?

I was less into art shows during that time, and more into continuously producing art. While working I was constantly thinking I was leaving something behind that would be discovered after my death. I didn’t care about exhibitions so I never set up any shows of my own, nor did I ever volunteer to organize projects. I worked and I waited (although I wasn’t even waiting to exhibit my work, I really wasn’t thinking about it at all). I did have some exposure with the help of Bogdan Iacob. In my first year he invited me to represent the university at a cultural festival in Sibiu, where I made one of my first iron installations. A chair you would sit on and ceramic masks would spin in front for you. I collaborated with Liliana Marin, she made the porcelain masks. The art debut in Cluj came later when I was already in my first year of masters in Poland. Bogdan Iacob asked to organize my solo show at the Museum of Art in Cluj Napoca. When I returned from Polan, The Paintbrush Factory was up and running, and that undoubtedly changed my artistic trajectory.

How did you become part of the Factory?

As a welder. During my masters I ran a small business very close to the Factory. I did a lot of the hardware for rehabilitating the Factory. Smaranda Almășan commissioned a modular frame made out of iron for her studio. When I went to mount the frame, I met a part of the artist community and I started going to the Factory art shows. Back then I was focused on business, constantly looking for iron works. I did some welding for Sabot, a gallery I worked with. Basically, I entered the Paintbrush factory as a worker, not an artist.

When did your artistic collaboration began?

It wasn’t long before I was invited to have a solo show at Laika gallery. I opened How it’s made in 2010, then I began collaborating with Sabot gallery. Meanwhile I started working with Adrian Ghenie, I did the wood work for the show Dada room at SMAK in Ghent. Thanks to Adrian, I found my place in the factory, he left me his studio when he left the country. Back then, solidarity was at an all time high, so things went smoothly: I worked a lot, my works started to sell pretty well, and naturally I started exhibiting more often.

And your identity?

My years in Cluj were all about work, I even gave up my double identity. I had no time to daydream. I had a single queer moment in Cluj that I would like to remember for the interview. I remember it was winter break, everyone was off home. The dorm rooms were very cold, yet I still shaved, dressed in drag and took some pictures with an old Canon. I remember I was freezing under my blankets, but I was happy to have a fleeting moment with my true self. The one moment I had some time for myself. Just so you can understand how hard I worked, literally non-stop, let me give you another example. I remember there was a big party in the dorms and I was welding away in my room. I made a sculpture using surgical tools that I welded together and caused the power to go out in the entire dorm. There was a huge scandal with all my colleagues. That kind of sums up my student years relationships, I was working all the time and disturbed the others.

Mi Kafchin – End of the World, 2017, ©Mi Kafchin

How did you decide to transition?

I was focused on my career until 2014-15 when a series of deaths scared me, and due to anxiety I discovered two cysts above my palatine bone. I had no idea what my operation’s success rate was and, paralyzed by fear, I came out to close friends. And I decided that if I survive the operation, I will begin my transition. I survived, I slowly began to transition in Romania, but with no access to information, I didn’t know what to do. I went to a psychologist. I properly started to transition when I managed to move. Here, in Berlin, it all became possible.

How did this impact your professional life? Was your career affected?

First of all, I sabotaged myself by not attending certain events where I was expected: but I wasn’t feeling comfortable enough in my own skin to show up. I suffered so much and I felt so ashamed that a lot of times I just disappeared without apologizing and I am sorry. After coming out, some distanced themselves from me, I distanced myself from others, but I was never discriminated in any way. I lost some collectors but managed to win over others. I don’t think it impacted my career. Besides, for me, my career means that I can work in the studio.

The body’s transformations is a recurring theme in your work and your approach is intersected with recent interests for feminism, both in the sense of recontextualizing alternative spiritual practices and an abundance of technology. An apparent duality that is the basis for many feminists’ preoccupations. Cyborg feminism? I also see your process of appropriation as what I call “queering the culture”.

My artistic process is relatively simple: I build everything up in my imagination and I don’t look for inspiration (nor do I steal from) cultural discourses or styles. I am myself. Naturally, certain things guide me and my intentions are to ease the tension of iconic images via a queer recontextualization, but above all else, I navigate dreams and memories.

Mi Kafchin – The Witch from Cucuteni, 2017, ©Mi Kafchin

POSTED BY

Valentina Iancu

Valentina Iancu (b. 1985) is a writer with studies in art history and image theory. Her practice is hybrid, research-based, divided between editorial, educational, curatorial or management activities ...