I was in Iași, it was 2012, end of winter, same as now. I was sitting in a café in Unirii Square with Mladen Stilinovic, an artist that had been invited to take part in the Periferic 8 biennial, and we were doing an interview about his artistic practice. To the question, “what made you choose a conceptual approach within the art context of Yugoslavia in the 70s?”, I remember he answered frankly something like “because it was cheap and accessible, easy to communicate and easy to understand”.

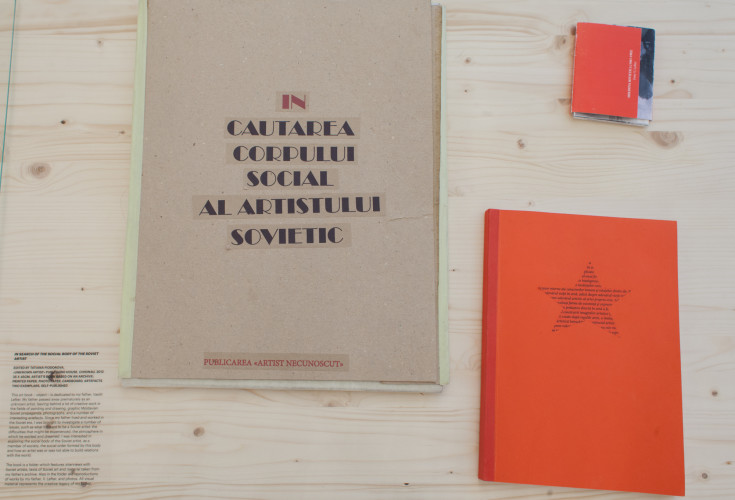

As I was browsing through the books exhibited by Tatiana Fiodorova under the title “When a book becomes a message” at the Czech Center in Bucharest as part of the project Future Museum (a spectral institution that definitely deserves a closer inspection), what struck me the most was the unexpected actuality of this statement. It seemed to be describing a historical condition of art in Eastern Europe, the belonged to a finalized phase in artistic production. Stilinovic’s hand-written documents and subsequent artist books, as opposed to the bureaucratic and impersonal aesthetics picked by American conceptual artists around the same time, also become fetishized in the meantime. The works he did then, now carry an aura that is specific to informal communication, the signs of autonomy and authenticity. And yet, the artist book, whether it is a photographic collection that has taken this format for narrative reasons, or it becomes a way of organizing the body of work for some potential archives, it remains to this day accessible to all, easy to handle and carry. It materializes a conceptual art that becomes a sort of installation, part of a rhetoric for archiving and remembrance, whose main stake is a confessional communication and an intimate dialogue that can be initiated in the apparently familiar frame that is offered to the public. When you read the books, you bend over a little, you touch the objects, you flick through the pages; there seems to be nothing standing between you and the (potential) story that is unfolding before your eyes, just for you.

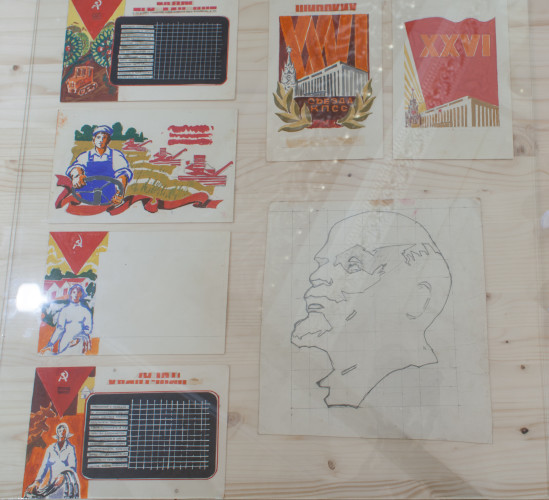

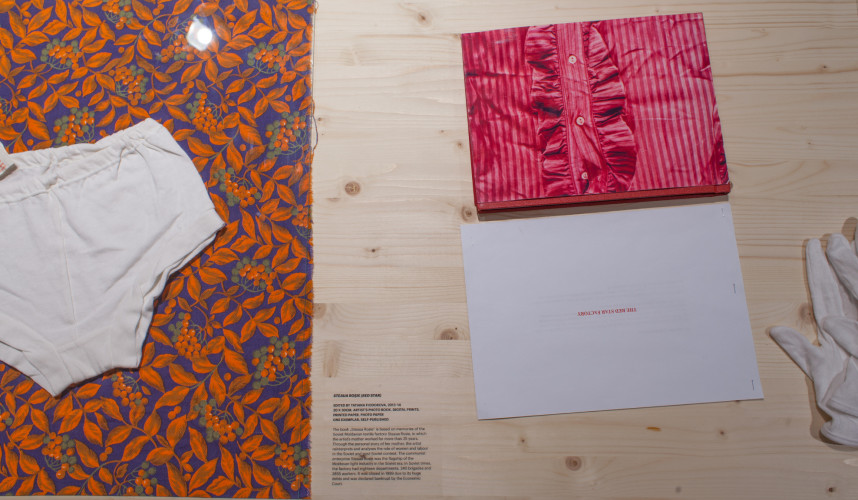

More precisely, the stake of Tatiana Fiodorova’s artist books seems to be investigating the possibilities, limits and effects of communications, its local fractures and modulations and, last but not least, the materiality of the statement, be it the noise of photographic images, the texture of the collected toilet paper, the particular aesthetic of the line in the drawings he has from her father or the ready-made objects inserted in the archive display. Her books question, in a rather predictable way, the construct of the archive as a political discourse and its inherent politicization, as well as its relationship to the politics of memory, cracked by assuming a personal counter-memory that is subjective and explicitly fragmentary. Tatiana’s appetite for the narrative also explores the fracture of recent history’s monolithic discourse, produced by pluralizing the narrative voices, the types of statements that are left to circulate and the resulting identities. This explains why the precise, strictly controlled, articulation of themes that appear to be dispersed in Tatiana Fiodorova’s Bucharest art show is less important than reaffirming a consistent strategy of work, which cuts out the profile of an artist capable of oscillating between the ex-soviet space and the unstable space of current geo-political configurations, by using multiple apparently personal filters for reading social life and the way it translates in artistic practice.

Tatiana’s books are exhibited in a slight museum format, on long tables, which apparently constrains the viewer to a linear reading. But you learn soon enough that it is more like an invitation to browsing, to making personal associations, rather than a cursive reading: the books are open, dynamic archives underneath their apparent structural confinement. Even if her books are part of a tradition of Moscow conceptualism, due to her affinity for the medium of books, and come close to the narrative fiction preferred by Kabakov, especially when their stories are built around the figure of her father, the artist Vasilii Lefter, or her mother, a worker in a textile factory, Fiodorova would rather collect “facts”, documents, objects, pieces of testimonies. Some of these become ruins of everyday life, or, in a less pretentious manner, dysfunctional objects that often indicate the bio-political discourse’s blind spots, exceptional states of generalization that have not been declared as such – like the soviet passport, the only form of ideological existence of those who haven’t the right to citizenship living in Transnistria. The fictionalization of personal history, reduced to a pure declarative existence by the communism described by Kabakov, is opposed by the opacity of the objects, gestures and images that refused to become transparent, to dematerialize or to get diluted in the language. Her stories hide a cynic, factographic realism that reminds me of Olga Chernysheva. Her books sooner exhibit possible discursive maps, that are imaginary but still concrete, rather than proper stories, in which History itself is being deterritorialized. And the archives presented in the pages are less likely to become anonymous or dysfunctional collections of images and objects that are specific to the Moscow, rather they can be, dare I say it, potential nomad archives. They were built by exposing again and again the striations, the mechanisms for institutional and state organizing which in turn build territories, establish hierarchies, build identities and organize the circulation of statements and people.

Las but not least, along with the identity topos which is found in all of these micro-archives, Tatiana’s books first and foremost question the work conditions (often linked to women) in the Soviet as well as the neo-capitalist regime – no matter if it is about the proletariat, about artistic work or the current state of the peasant. More precisely, her artist books materialize various frames in which they are produced. For example, the toilet paper in Bucharest institutions, whose quality says a lot about the respect the institution has for the public, the typical commissions of the “state financed artist” in the Soviet period (replaced with new ideologies for applications to various institutions that are capable of financing artistic projects), the peasants’ role in building the Soviet Union and their recent transformation in precarious, nomadic workers.

Coming back to Mladen Stilinovic’s statement on conceptual art as being the poor man’s medium, I think that precisely this precarious state, which is both assumed and discussed, could be the reason why Tatiana Fiodorova continues to use this hybrid medium that is unpretentious yet familiar, void of monumentality and importance.

Tatiana Fiodorova, When a Book becomes a Message, was between 27.01 -11.03. 2016 at the Czech Center in Bucharest as part of Future Museum.

POSTED BY

Cristian Nae

Cristian Nae lectures in history and theory of art and the Arts University in Iași. He works between visual studies, aesthetics, exhibition studies and geohistory of art....

Comments are closed here.