Because a series of notion, like uncreative writing, uncreative genius, conceptual poetry, experimentalism, appropriation, etc. have finally begun circulating among our critics and authors, terms which were lifted, thought of, and integrated into a system whose analytic instruments do not allow for their appropriate understanding, we find ourselves in the unfortunate position of possessing in our language only the hard core of these concepts/notions, without the possibility of their marginal areas and of the ramifications that would have allowed for an opening towards another way of approaching them. Among them all, the notion of creative genius, though the most frequently utilized, is perhaps the most inappropriate because, by keeping the term ‘genius’ in the syntagm, it can lead to false approaches to how the uncreative author, or, rather, the scribe, should view himself in relation to what he writes. Appropriation must be understood outside of economic thought, by means of an eco/logical resumption of the system. Behold. How can you reduce to explicit mentions the presence of Plato in Aristotle’s texts, of Descartes in those of Leibniz, of Hegel in those of Marx, and, in general, of these privileged interlocutors, transported by every producer in all of his writings, masters whose schemes of thought which he [the producer] has assumed to such an extent that he can only think through them and in them, intimate adversaries that can dictate his thought by imposing on him the field and object of conflict? Therefore all literature is just a form of epigonism, and what appropriation does is to denounce the expropriation of productive activity, of which art has proven itself guilty for so long, by disguising it behind the ideas of genius and originality (even in its milder version of “unique” reassembling of previous ideas and discourses). The reutilization and assumption of epigonism (i.e. of non-value) in its radical form is what ensures the ecology of literature.

In this respect, I found it relevant to see what just such a scribe, Sebastian Big, has to say about his most recent “productions” (Masiv [Massif] and Poetica non-separabilă a interfeţei [The inseparable poetic of the interface]), but also about his non-polluting activity in a literary “environment” covered by the thick smoke of unfettered burning.

In one of your recent projects you state that: “in 2016 I let the machine replace me, not out of laziness, but out of modesty. I tried to reconnect with the mistake.” There has been a lot of talk recently about this need of the author to abandon the production of texts/materials to add to the world, and to instead reuse/recycle already existing material. It is an ecological gesture, in the end, a gesture that you tie to renunciation: “to let an Other speak instead of or through you.” A gesture of “modesty,” of erasing the name. You equate this Other with the machine. What does “the machine,” this voice that helps you replace the arrogance of the producer, mean for you?

It’s not necessarily about an external machine, but rather the individual’s machine-like side. Of course, there is a kind of exteriority to the machine (be it internal or external) in relation to the Human being’s general/cultural understanding. Precisely because accepting the machine into our soul means the renunciation of what we believe we have built with so many sacrifices in terms of identity. I try as much as I can to work out and stay in shape for future non-identity performances. I like to think that I’m working towards bringing my modest contribution to this sport.

Anyway, Identity is the (cultural or generic) Establishment’s favorite food, and the battle against identity is also a battle with the its [the Establishment’s] Grand Ponzi Scheme. Maybe it’s here that the truly ecological stakes of my story lie. In quitting cultural (and/or social) fossil fuels.

What consequence does this assuming of modesty have on literature? How does it change the notion of author, but also the relation with the “specialized” receiver?

For me personally I think it’s a win-some lose-some situation. The loss, as I was saying above, is in terms of identity. The machine presupposes repetitivity, so the gain is in terms of the optimization and refining of the production process. And this brings with it, of course, new means of expression, which are, if you ask me, the prime mover of “literature.” As for the specialized receiver, I think this will force him to leave behind prejudice. To question the idea of “specialization” itself. Maybe what would be of more help would be a process of de-specialization, an escape from the scheme of “literature,” an escape from the idea of “scheme” or “schemes.”

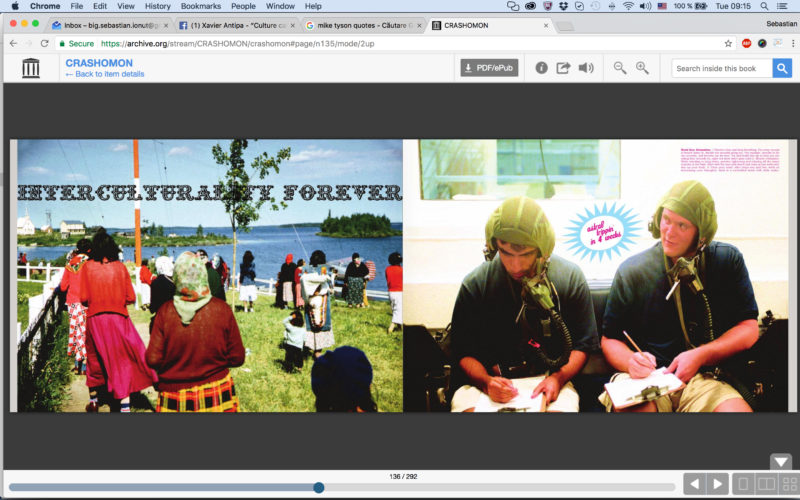

In the volume published last year by editura frACTalia, titled Masiv, you use alongside the texts themselves some images by George Crângașu. What is, according to you, the relation between text and image in this volume? How would you describe this relation in general, beyond what you have done with Masiv?

With George it was interesting to see how we could each emulate the other’s technical perspective. That implies me writing like his images and him making his images resemble my writing. And to see how well they could morph into one another. To be honest, I don’t see a difference between text and image (any longer). They’re both means of visualizing information.

Regarding performance and its actualization, the selection and generation of discourse: why did you choose a geography text when you laid out the Masiv [/massif] on the page? What part does the machine play in actualizing performance?

In the case of Masiv, the machine that actualizes the performance cyclically is the body. I go to the mountainside often, especially in winter. There are two types of movement there, one is climbing the hill, the other is skiing down the slope. An uneven motion of accumulation, and another resembling a flow, surfing. This is basically how I operate with information. I have periods of mechanical material accumulation, then moments when I “slide” and something like a production comes out. Proportionally, accumulation is 98% of the process and involves, obviously, sweat. The pleasure is brief, but the taste is long living.

And since we were speaking of technique, of technology and Masiv, I have to make a pretty important note. To venture into this type of nature you need very good skiing/mountain climbing technique, and very technical equipment, very light skis, avalanche beacons, air-cushion backpacks, basically the spearhead of research & development in many domains. But technique and technology are only “vessels” that help you surf nature. To be able to venture as deep as possible into something that is a priori extremely hostile. Masiv is a kind of “heart of darkness,” the place where the ends of the circle meet, where nature and culture, poetry and technology seem two sides of the same coin, which is life.

Another “ecological” matter, how would you have thought out/imagined/rewritten Masiv if you would have published it electronically? Do you think that printing will disappear, that the paper book will be forgotten?

The volume would have looked the same digitally. I planned to make an online game to tie into the volume, where users are mountains and all they do is look around. And the more they look, the higher they get. Like who looks more sees farther, or above others.

I don’t think paper books will disappear, and as long as the paper is recycled, I don’t have a problem with the physical support of the text.

“The real disappears in the heterogeneity of the regime of advanced technologies’ temporality, losing its unit of time in the favor of a unit of place (in the sense of a concentration/delocalizing of the place in the interface) in which perspective contracts (in the sense of a loss of volume), transforming (therefore) into a surface (deprived of contact) which, through cutting-edge technologies, through mass communication media, becomes a transparency” (from Poetica non-separabilă a interfeţei, Editura khora impex, 2017). Tell me a bit about this “Real” and the relation that you think exists between it and “reality.”

These ideas have already become classical in a way. Let’s say that on the one hand there is “that which is” and on the other hand the discourse about what is. What I’m trying to say is that we’re now faced with a question of means. Both in the sense of a means of transmission as well as of middle, of a mathematical mean between two entities. What results is a hybrid that is neither “that which is,” nor discourse any longer. That’s what my poetic practice aims, to develop a poetry of means.

Should the referential dimension of a text be rethought/re-questioned or is it a simple phrase that is no longer of any use to poetry?

I think that as long as it stays authentic, referentiality is not something that hurts one’s practice.

For instance, I’m a guy coming from (and staying in) the middle class, so I produce middle class poetry. I’m a mediocre individual so I produce mediocre poetry, poetry of mediocrity. Of course, coming from the middle class, I’ve been educated to be competitive, so I plan to write the best mediocre poetry ever written.

I was speaking above about means. I’m interested in the poetry of the middle. Technico-tactically I try to see how close to the middle between Zen and ecstasy I can situate myself. Routine, routine, runtime.

What does postcommunication keep/(re)use from the strategies of communication?

Well, I think that this age (of postcommunication) is a linguist’s wet dream. Big data sets. Syntax prevailing over semantics. I think we can only now speak about strategies. Until now these were, like, a sort of mantras of communication, a rural/craft communication, you could call it. I’d say that in terms of communication we’re living very innervating times.

Is this “literature” a heritage of the avant-gardes, or is it a mistake to view them in continuity? Is the point we’ve reached the consequence only of radical ruptures?

There is an affinity for those movements, of course, but it’s rather something strategic, technico-tactical, like repeating a practical, pragmatic movement. I’m not interested in their context and content, but in the angle at which they approached the problems, the mindset in which they operated. In fact, I feel just as influenced by Nansen, Amundsen, or Scott. It’s the same movement of sporty, scientific, “literary,” but by no means colonial, exploration. Like these scientists, the example that must live on from the avant-garde movements is exactly this anti-colonial/ecological approach to the environment (be it cultural or not). But let’s leave anti-colonial/post-colonial poetics for another time.

Note about the subtitle: I use “tactics” – in the expression “an organic tactics of a bio-bourgeois poetics” – in Michel de Certeau’s sense, as a consumer’s tool with which to fight the establishment’s production strategies.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Iulia Militaru

Iulia Militaru is Chief Editor of frACTalia Press and the Editor in Chief of InterRe:ACT magazine. After a few children’s books and her study "Metaphoric, Metonimic: A Typology of Poetry", her first...

www.fractalia.ro/

Comments are closed here.