This is what I asked myself when I first heard about Because in our dreams we took risks, an exhibition curated by Diana Marincu, at the Art Encounters Foundation.

Perhaps you already know, or perhaps not. Art Encounters Foundation is a private institution owned by a large real estate investor from Timișoara and many of their past events were somewhat problematic: on one hand they would exhibit a militant artistic discourse for the rights of minorities, of the precarious ones, for the politically unaligned – and on the other, they would exploit those very people in various ways (for example, inmates for the first edition of Art Encounters Biennial or volunteers for the last one). For some context, I recommend reading through this, this or this article.

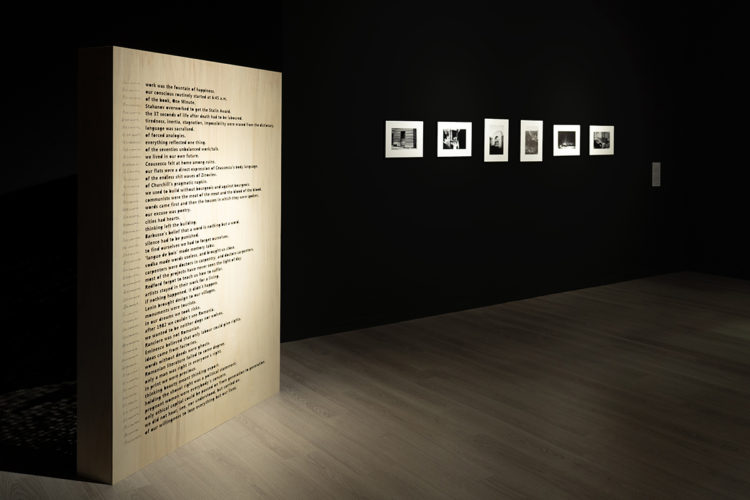

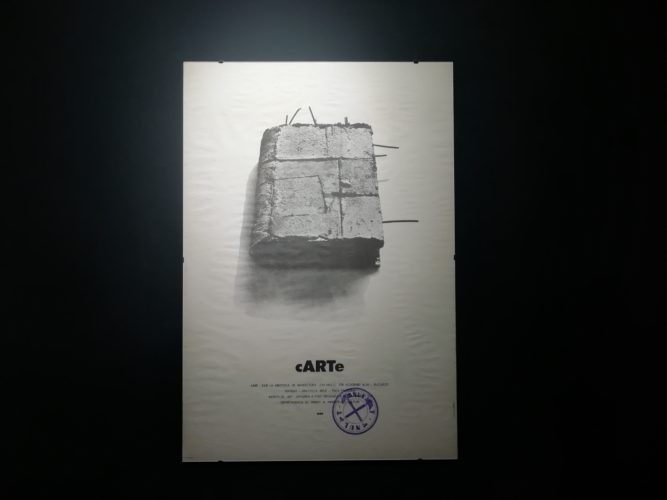

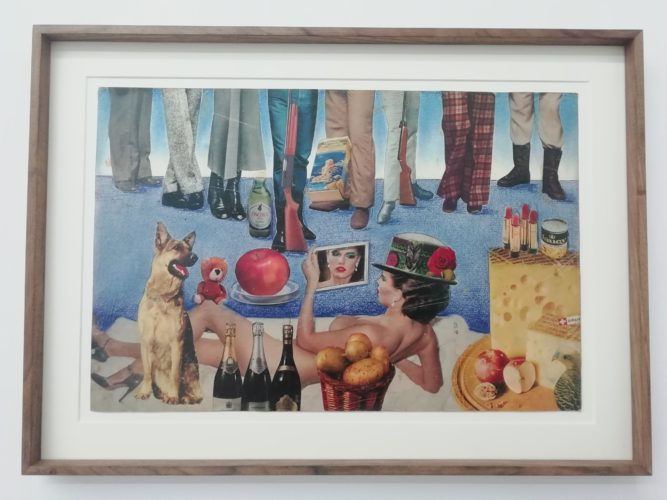

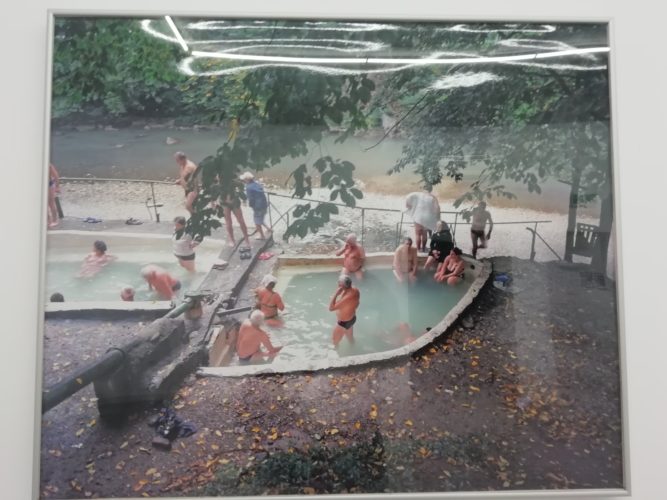

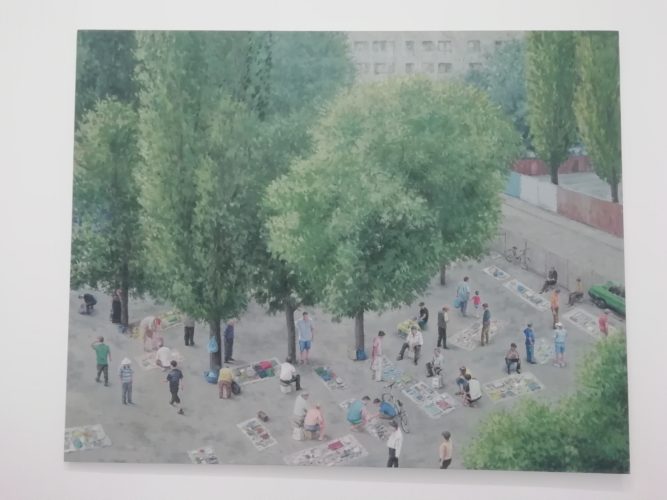

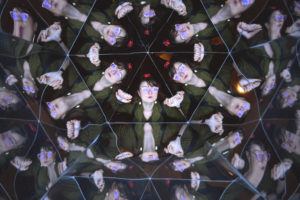

From Boxing by Ion Grigorescu (1977), collages by Ion Bârlădeanu to contemporary photography of Bogdan Gîrbovan and Michelle Bressan are some of the works one could find in the exhibition. Another room reunites works from Bertalan, Ioana Bătrânu, to Ghenie, Nancă, Scriba, Chintilă, Flondor or Lupaș. Mircea Cantor’s “infinity” (Epic Fountain) is alone in one chamber and it is read as “an infinite column tying human DNA to cosmic space”; why not an infinity composed of fragile, but solidary parts? Observing Cantor’s practice in Paris, his aesthetics are minimal, even precarious, to point to migration or poverty or other contemporary issues; but not imbued in an anthropocentric approach as the description would suggest.

Why am I writing about this exhibition? I’ve also asked myself: why offer media space to an institution financed by the big real estate capital?

…because it opens up the possibility of problematizing contemporary curatorial discourse.

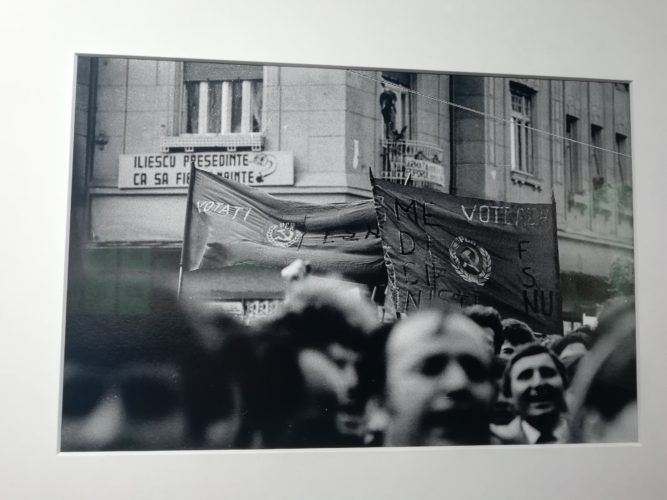

…because it took place in Timișoara during the celebration/commemoration of 30 years since the Romanian Revolution in 1989.

…because it gathered numerous valuable contemporary artists:

Ioana Bătrânu, Ion Bârlădeanu, Ștefan Bertalan, Michele Bressan, Mircea Cantor, Andrei Chintilă, Harun Farocki & Andrei Ujică, Constantin Flondor, Adrian Ghenie, Bogdan Gîrbovan, Ion Grigorescu, Radu Grindei, Ana Lupaș, Alex Mirutziu, Florin Mitroi, Vlad Nancă, Miklos Onucsan, Andrei Pandele, Christian Paraschiv, Șerban Savu, Decebal Scriba.

What is the discourse that reunites all of them, with all their formal differences, regarding the artistic medium but also the context (some works are 50 years old, some others were made only 2 or 3 years ago)? And how does this curatorial discourse manage to place all of them in the context of the Revolution, considering that the exhibition opened in December 2019 and took place at the same time with the celebration/commemoration events? What is, in fact, the conceptual basis that reunites all these works? Are they in some sort of dialogue or is it more of a regime of silence, a silentio stampa, disturbed only by the vociferations and shootings in Videogram of a Revolution (Farocki & Ujică)?

“On which basis can we trace parallels or institute equivalences, if not even alliances between different positions? What particularly can become comparable? What is added, what is mounted together and what differences and oppositions are leveled in favor of establishing a chain of correlations?”, problematized Hito Steyerl in Beyond Representation.

And which is this chain of correlations here?

Because in our dreams we took risks, one of the lines of this manifesto, transforms the burden of a verdict into a connecting knot for different generations. This knot temporarily weaves together chronological threads, historical narratives and cultural landmarks that make up a multi-layered image of the art before and after 1989, as it is represented in the present exhibition”[1] would be the answer of the exhibition.

Then, which is this connecting knot?

The discourse eludes signifying this „connecting knot”, and the expressions keeps an obscure meaning, impalpable, without a referent, and this cannot be random. Is the key of understanding in the title of the exhibition and in Alex Mirutziu’s poem? Does it transform this showcase of art objects in something more than their basic sum?

TLDR: Nope.

Because it does not even set out to do so.

Because this is what a decontextualizing discourse does: it sets aspects aside, it makes them invisible, it ignores the context to suggest – subtly, low-key – a certain sense that only the privileged[2] ones can reconstruct for themselves. For once, I am talking about a logistic privilege of time management: not everyone’s work allows visiting galleries during their open hours. Secondly, it is the structural privilege of access to quality education that would allow for the profound, contextual understanding of the works as well as imagining potential “dialogues” between them.

Mirutziu’s poem has this gift, this immense capacity: it can be continued endlessly and so it invites to dialogue, it is a curatorial opportunity. Only that it remains a missed opportunity: it does not tell a story neither for those born after 1990 nor for those who lived during Ceaușescu’s rule. The works are isolated from each other (Cantor’s Epic Fountain sits alone in a room, Grigorescu’s Boxing is in another) without being even tied back together at least through some exhibition design artifice. Yet, such an exhibition design would have meant owning up to a stand point regarding communism and the Revolution – while the aim seems to be, as I was saying, decontextualisation.

However, the fact that Diana Marincu extracts from Mirutziu’s poem precisely this verse: “Because in our dreams we took risks” cannot help but make one curious. At least a bit. The poem is a critique of communism from a subjective, almost dreamlike, memory (Ceaușescu among ruins – something almost hilarious considering the degradation today) and material (vodka has kept us close). The majority of the verses are more critical, yet the elusive “Because in our dreams we took risks” is chosen. Why only in our dreams? Why in the past?

Is it, maybe, a sort of confession that, before 89, we manifested our courage only in our dreams or is it that, even though we are now free [3], we don’t take risks, not even in our dreams? Not in the way Ion Grigorescu used to do it, anyway. Maybe if we wrap everything in an artistic format? Here lies the central point of what makes this exhibition problematic: subversive gestures are objectified and become poor images, regarded aesthetically and not politically.

Who is the target audience of this exhibition?

Probably potential art buyers. The current seems rather a marketing instrument through which the value of some works and/or artists is increased. This is the reason for which only the aesthetics matter. A significant part of these works have also traveled to Paris, to Ex-East[4] exhibition, curated by Ami Barak, Diana Marincu’s colleague. This is why it doesn’t seem desirable for Art Encounters to play the dialectic game of the images, to allow them to leave the Foundation’s building through cultural mediation programs (for instance, Videogram of a Revolution and the photographs could have traveled in schools, digitally, with the help of the community, people who had already collaborated with Art Encounters for the Biennial).

The depletion of document-images

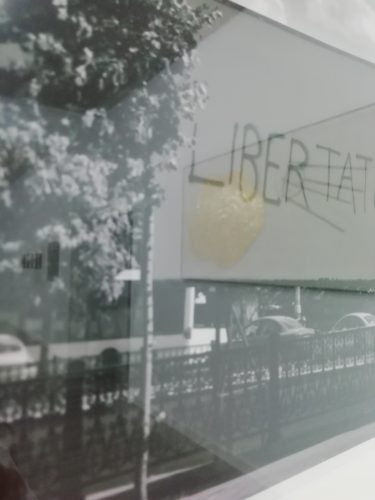

Within the exhibition one could find images from the Revolution (in the same room with Mirutziu’s object-poem, the central piece) – Radu Grindei, Miklos Onucsan, Andrei Pandele, as well as contemporary photos that gaze towards socialist architecture: Gîrbovan’s project and Bressan’s brutalist architecture. Are photos becoming depleted images through anesthetization and de-politization? Few photos are present in the exhibition and they are solely responsible to create context. Yet, they objectify and seem to abandon their subjective histories in exchange for the status of art objects. “The depleted image (…) floats at the surface of temporary and doubtful databases”[5], just like Because in our dreams… remains, in the end, a temporary and doubtable exhibition. Because it does not leave much behind.

Using politically engaging images without creating a frame so that they can perform this engagement (and here I mean various contexts of discussions around these documentary images) only hijacks their subversive power. They remain in the background, mere “fossils in which a force relation petrified” (Steyerl). The curatorial discourse does not ease understanding: there is a certain relation of force between the photographer as an observer of the Revolution who took a real risk going out in the streets in those days and another relation between a photographer who shoots architecture – Bressan, or the one who “takes the risk” of inviting his neighbours into his photo project – Gîrbovan; there is a certain force relation in producing a subversive video during Ceaușescu’s times and another in producing Videogram of a Revolution (Farocki&Ujică) and exhibiting it in an art space.

Because a discourse without a context is just a discourse, let’s call it “neoliberal”, that assets liberty and equality within individualism, and, implicitly, the individual’s freedom to read as he wishes and as he is capable a written or visual text. Without taking on the responsibility to build a solidary space of sharing/ discussing/ negotiating meanings. More precisely, without building a context in which different “little histories” can be put together, without the pretenses of being the Big History. Here’s a pragmatic example: during the days for the Memory of the Revolution, there could have been discussions, get-togethers with people within the community in the gallery.

I got to Timișoara in the context of a collaboration with Memories of the Fortress[6], a project which refreshes the memory of December 89 within the Timișoara community through cultural events with “light” content, that brings people together to ease them closer to the subject. I worked on editing the Memories of the Fortress catalogue, which reunites documented artistic projects and stories from the community (real memories from the Revolution). I believe this project’s team did much more to activate the local community compared to AE, yet, in the year before the start of the Timișoara Cultural Capital 2021 programme, I would have been happy (and will be) to see more synergies from local actors. Some of them were telling me, some months ago, that “Timisoara is a larger village”… Just that the different alliances and practices of those local cultural managers prohibits – at least apparently – building powerful local solidarities.

“30”

A little further away from the Bastion, in the Garrison building at Liberty Square, the Timiș County Direction of Culture proposes yet another exhibition. The effort is applaudable because it elegantly brings back a years-old discussion about transforming this building into a Museum of the Revolution. Here we find yet another photographic serie on the same subject, with some more context provided; a welcomed initiative to pressure towards transforming this building into public space.[7]

“A way to live and die properly, as mortal beings, in chthulucen is to unite our forces to reconstruct refuges and to make possible, at least partially, the recuperation and reconstruction of the biologic, cultural, political and technological, which need to encompass mourning for the irreversible losses”[8], wrote Donna Haraway. This case was about mourning. It was about gains and losses. But the exhibition space and curatorial concept of Because in our dreams we took risks make no room for that. In the tradition of extreme individualism, each should build such a mourning space within him or herself. For example, also in December 2019, not so far away from Art Encounters, the Heroes March was organized – a potentially new public, of hundreds of people, who could have passed their doorstep and could have commonly shared memories, experiences and losses, to understand them and heal them.

The exhibition could have helped in building a community spirit, a dialogic and empathetic one. It could have served as a frame for discussions – feminist, artistic, intersectional ones – about our own histories, about our collective memories and collective oblivion, about what we have gained and what we have lost in these 30 years, socially and artistically. Yet, building such a space requires not only tremendous inner resources but also logistic support, which is capital. Therefore, by not invest as such, Art Encounters remains in the paradigm of the dream.

At the same time, even in a marketing paradigm, to build a healthy and durable brand, the strategy ought to bring real utility to the brand audiences. Be it product, logistics or communication, it is utility to the consumer that can transform any brand into a love mark. I would be enthusiastic to see such a transformation for Art Encounters into a love brand that puts its publics at the center, bringing them real utility in cultural education, even if their motivation would be the accumulation of sympathy capital.

We live in a period of evasion – even more visible now, with the coronavirus pandemic. We avoid truth and we cannot see more than fragments, subordinated to various regimes of truth. “Make kin, not babies” was a saying. Could we possibly hope to create kin-like connections that would weave a communitarian network of experiences, ideas, know-how, resources? Could we maybe be solidary and take risks together? There’s still time (?)

The exhibition Because in our dreams we took risks took place between December 12th 2019 – February 7th 2020 at the Art Encounters Foundation, Timișoara.

[1] https://artencounters.ro/en/despre/

[2] Myself included.

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e6dgfhxBK9Q

[4] I wrote about it, in Romanian, here: Ex-East. Still east.

[5] Steyerl, Beyond Representation, p. 6

[6] The Memories of the Fortress

[8] Donna Haraway, Antropocen, capitalocene, plantatiocene, chthulucene

POSTED BY

Raluca Țurcanașu

Raluca Țurcanașu is a former Account Manager who wanted to write. She's trying to blend visuals and words to tell compelling cultural stories. Raluca has been following image studies in Bucharest (C...

ra-luca.me/

Comments are closed here.