The Danube-Black Sea Canal, seen as the greatest achievement of the communist age in Romania, is a node, or a bridge between historical eras and political ideologies. Its construction spans multiple decades, being inaugurated shortly before the revolution, and today it is talked about through the lens of the deaths it caused. The fragmented history of the Canal gained a mythical dimension after the revolution, being heavily influenced by the stories of those who worked there and survived. This is where it got the name “the Death Canal,” a periphery of the communist center of power with huge economic stakes, which, it seems, has yet to achieve its full potential.

What does the post-revolution generation know about the Danube-Black Sea Canal? Stories from their grandparents about work camps and tortured political prisoners, memoirs from former inmates that talk about the horrors that took place there in detail, museum rooms dedicated to the Canal, with reproductions of cells and maps hinting at the existence of an extermination system in Dobrogea. All of these represent the center of the Canal’s history, coalescing into a portrait sketch of the Canal in contemporary collective memory. But what about the edge? What about the details of this sketch? How do we navigate the relational system between center and periphery, between facts and history, between political interest and social need?

*

In his text “Real Time Systems,” published in ArtForum in 1969, art theorist Jack Burnham looked at the stakes of contemporary art in investigating various more or less corrupt social systems using the available technology. Burnham put forth the role of the artist in demystifying various power relations or systems governing the art world and not only.

From the ’60s onward, the artists making this kind of art have waded deep into theory in an attempt to reveal the many facets of contemporary society. The troubled history of these last 60 years has raised the status of the contemporary artist to the that of researcher of alternative narratives that complement the mainstream historical/social/political one. On a local level we can speak of multiple generations of politically engaged artists that have criticized the dominant relational systems of the post-communist reality we find ourselves in. Given the problematic relation we have with our own historical and political past, on a national level, it is no surprise to see local artists’ fascination for sites, artifacts, and events from the communist period that have remained unexplored to this day, 30 years after the revolution.

A pertinent example in this sense is RO_ARCHIVE, an initiative started in 2010 by a dynamic group of artists, curators, and sociologists under the umbrella of the Bucharest National University of Arts with the purpose of researching the cultural archives of recent Romanian history (until then forgotten), with special consideration for texts and images. The 2014 D Platform set out to continue this research process, under the guidance of curator and theorist Raluca Nestor Oancea (one of the organizers of RO_ARCHIVE) and artist Iosif Kiraly, professor of photography at UNARTE. D Platform focused on the Romanian Danube region.

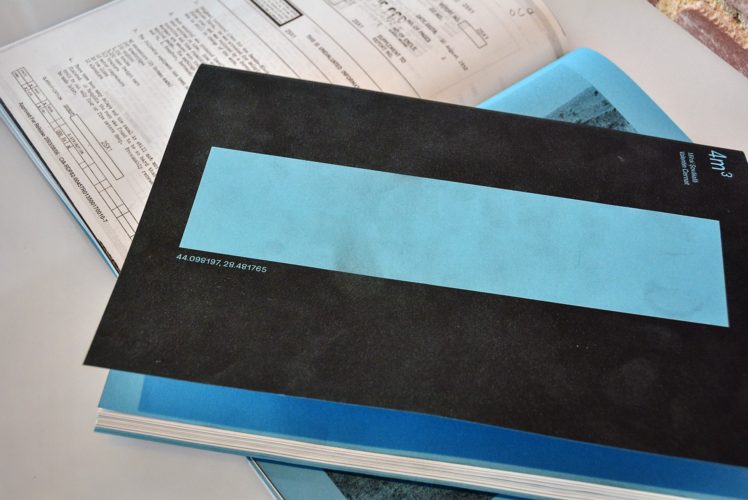

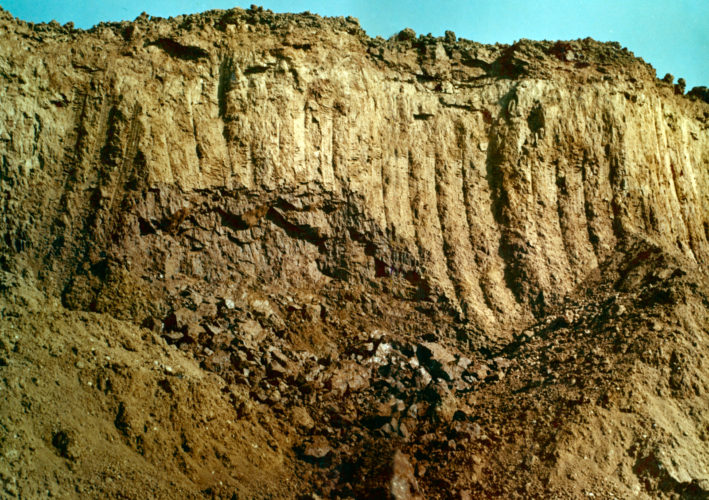

The project 4m3 was started in 2016, in the context of this platform, by Valentin Cernat and Mihai Șovăială, two visual artists that tried to understand the mythical history of the Danube-Black Sea Canal. “Strictly speaking, there were two distinct plans for building the Canal and 2 phases in its construction. These two phases are generally confused nowadays – out of ignorance or not. The first project stretched between 1949 and 1953; the second, between 1975 and 1987. The labor conditions, as well as how much the laborers were paid, differ much from the first phase to the second one.”[1] It seems only the first period has remained ingrained in the dominant public discourse: the Canal is remembered as a labor colony for political prisoners that has seen many victims of administrative abuse and inhuman working conditions. This view informed the artists’ initial approach. The two came armed with the superficial information about the Death Canal, choosing, as an approach to better understand the territory they were exploring, to reproduce the physical effort put in by the prisoners working there. So, they dug four cubic meters of earth every day and documented the action in photos.

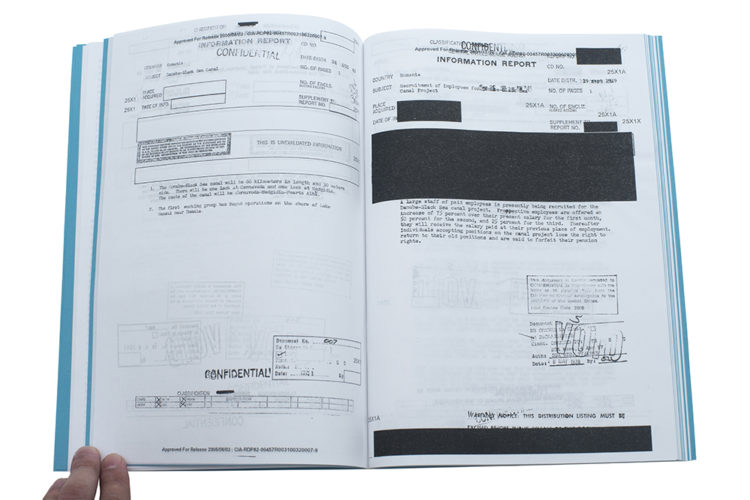

However, the artists soon realized that their initial approach lacked the critical apparatus to properly cover this vast and, as it later turned out, very generous subject of the Canal. So Cernat and Șovăială continued their research, writer and theorist Ovid Pop joined the group, and they produced a small publication starting from 4m3, offering a different perspective on the Canal: the photographs from the preliminary phase of the project are now accompanied by a series of CIA spy reports from the ’50s, which documented the first phase of the Canal’s construction. These surprising documents, which were declassified in 2008, complement the official, predominantly political perspective around the objectives of the Canal with a structured, administrative perspective which reveals some previously unknown organizational aspects of its construction.

This represented a turning point in the project Cernat and Șovăială had begun: symbolically, their preliminary digging unearthed new information, a new general perspective on the Canal and the countless new links waiting to be made. For, in the end, that is what the Canal represented: a naval, commercial, political, and social link between many possible narratives. And for that they had to dig deeper.

4m3 developed therefore in a number of forms: multiple presentations of the publication in national art spaces, together with readings, art installations, and international exhibitions that included performance art, sound, and poetry. The most notable in this sense was the performance in Brussels in 2019, at the very fittingly named 2m3 gallery, where the Danube-Black Sea Canal was showcased alongside the Brussels Canal. The history of the latter stands under the sign of colonialism and expansion, an extremely different ideology from that behind the Danube Canal, but with an almost identical relational system, canals being instruments of modernization used in a global trade structures. Built almost a hundred years before the Danube canal, the Brussels-Charleroi Canal also started out in a peripheral position, being at the edge of the economic system in the 19th century. Belgium, which was at that time a young new state abounding in cheap labor, wished to transcend this position, to become part of the dominant force of global development. The Belgian canal certainly facilitated international trade, becoming a model for the western-European colonialist-imperialist infrastructure. The Danube canal on the other hand, which also became a model for communist infrastructure, was built with other purposes besides the commercial one: mobilizing the work force, urbanizing the population, irrigating the area, and, generally, the wellbeing of the Romanian people.

4m3 stretched over 3 years and represented a comprehensive artistic and investigative project that investigated all the facets of the Danube-Black Sea Canal, an organic project that evolved and diversified. Cernat, Șovăială, and Pop sought, on the one hand, to reveal the cultural-political reasoning that has been producing and disseminating narratives about the Canal throughout recent Romanian history, and, on the other hand, to open up the topic of the Canal to an artistic critique that connects art to the great consumerist infrastructures of the global economy. There has indeed been a lot of talk about the Canal, but what would the Canal have to say?

Later in 2019, the project took a new turn: under the name Alternator, with an eponymous website gathering together all the data, the Canal receives its own voice. Valentin Cernat and Ovid Pop opt to look not to the Canal’s past but to its present, to what new connections and meanings it is able to generate now. Alternator focused on collective works and subjective narratives from those who were or still are in one way or another bound to the Canal – workers who took part in its construction, cultural workers who produced and disseminated works about it, or participants in the initiated art projects.

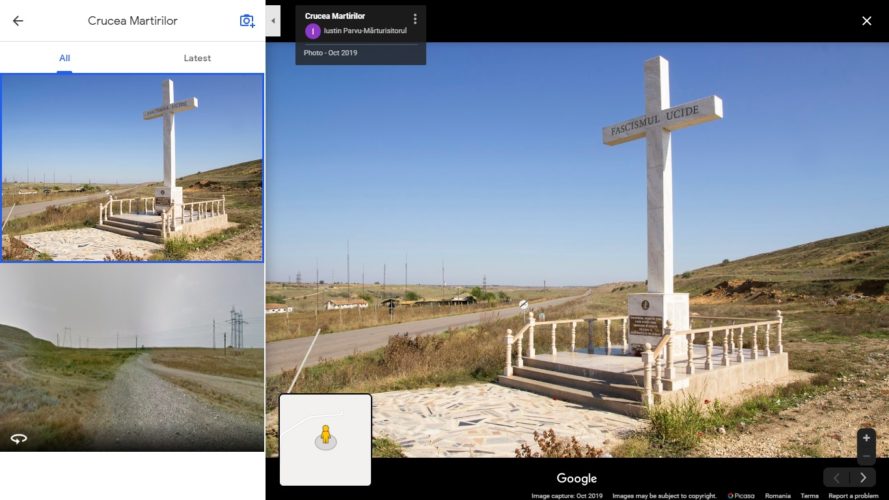

The focus of the research for the 2019 project was monumental art at the Canal, which, in spite of its peripheral status, is very expressive when it comes to the various historical narratives surrounding the Canal. The White Gate (Poarta Albă) Monument, sometimes referred to as “a column of infinite pain,” is a column made up of crosses bearing the names of labor colonies where inmates died, and it is certainly representative for the current official narrative around the Canal’s construction. Then, there is the Canal’s monumental mosaic, which can be seen from the Bucharest-Constanța train and which honors the contribution of the Romanian military, marking the completion of the Canal’s first 40 kilometers – a monument that testifies to the Socialist narrative, one of the propaganda tools meant to instill a sense of patriotism. Perhaps the most surprising is the Monument for the Confession of Fascist Crimes (Monumentul Mărturisirii Crimelor Legionare), a cross dedicated to the victims of Romanian fascism in the Second World War, placed on the spot of a former colony, one of the few instances where the Romanian Orthodox Church actually acknowledges the crimes carried out in its name.

But the Alternator’s most visible monument was the Monument to the Socialist Youth, also known as the Winged Angel (Înger Înaripat), created by artist Pavel Bucur in 1986. This edifice, which remains spectacular to this day, was built in the middle of nowhere so as to be visible from the Canal. But this giant steel wing, also placed at the periphery, is hard to reach and seems to belong to nobody today. In spite of the artist’s attempts to move the monument next to the A2 motorway, which would make it more accessible, the Alternator team has discovered in its research that no public institution seems to be willing to take responsibility for it. So, the team decided to facilitate its return to those it had been dedicated to: the youth. Together with students at the Mihai Viteazu High School in Medgidia, they organized an exhibition at the Culture House of Unions (Casa de cultură a sindicatelor) in Medgidia, as well as a few on-site interventions at the monument, where the students reflected on what the monument and the Canal meant for them. The works in the exhibition were made exclusively by local students, without interventions from the team, and the name was chosen unanimously by the students: The Space of Fragile Youth (Spațiul Tineretului Fragil). In the case of this exhibition, the periphery was the one that gave voice to the Canal, addressing itself to a peripheral audience. Up to this point, the Canal’s history had been deterritorialized from the periphery and brought to the center, in the case of the local and international exhibitions, visited by a certain social class; now this history, together with the new research produced by the group, is brought back to the periphery to be presented and discussed together with a local audience.

All this can be found on the Alternator website, which contains all the information gathered about the Canal as well as the art projects made thus far. The site itself can be seen as an artwork, with a nonlinear navigation style and with numerous links to information that is presented in an unconventional style, with the purpose of engaging to viewer to launch in their own research.

In 2020, the team began working on a new site, this time intended to gather all the archive material relevant to the history of the Canal from official sources, together with material from their own research. Arhive-narative (Narrative-Archives) came into being from the desire to make the Canal’s voice better heard through by continuing the efforts of Alternator in a manner that only feels natural. The new site emphasizes the notion of the narrative: how dominant narratives are formed, the fragmented archives they are based on, and the fact that other narratives exist beside the official one.

The site raises new questions about the ways one can postulate the “truth” about the canal. The troubled and tainted history of the Canal has been preserved mostly based on subjective testimonies (mainly the memorialist literature dominating the topic). Furthermore, these personal testimonies are at the root of many artifacts that make up the official frameworks of presenting history, like the National History and Archeology museum in Constanța, setting and normalizing the “Death Canal” narrative. The team therefore sought to highlight the fact that there are multiple forms of subjectivity in the discourse around the Canal, and the dominant narrative of the present is only based on one of them. That is why the team tried to establish contact with as many people as possible who could contribute their own narratives: an advert broadcast on a Constanța radio station made sure that the message got to people from all corners of the city. These interactions proved to be extremely varied, as was intended, from the life stories of the interviewees to their reactions when faced with more or less sensitive questions. Some of these discussions are on Arhive-narative, though the most revealing conversations, among which those with the higher-ups at the above-mentioned museum, are not available online at the moment. Is institutional pressure to blame?

The new site is split into two sections: on the one hand there are the official archives, from various sources (the Administration of Navigable Canals based in Agigea, CNSAS, the national archives, scholarly works, materials from the artists’ own research) and on the other hand there are a series of video interviews made by the team with people that had direct contact with the Canal (from different workers with different positions, engineers, and clerks of the Administration of Navigable Canals, to various cultural workers). The Arhive-narative website, like Alternator, was designed to stimulate the user to draw their own conclusions. The specific design, with the official information on the left-hand side and the interviews on the right, suggests both an antithesis as well as a possible correlation of the given pieces of information. The official archives support the dominant discourse, while the interviews offer a subjective perspective on this discourse. In this sense, they complement one another, and together they help us form a clearer picture on the Canal’s history. But we must also keep in mind the fact that the antithesis of these narratives is rooted in the power relation between them: the official archives stem from the sources of power, which lack the subjective dimension of social classes considered inferior and, therefore, irrelevant. In other words, it is again a matter of center and periphery.

Together with the website, a publication was produced where various artists, writers, and theorists were invited to contribute to the truly rhizomatic development of this ample project about the Danube-Black Sea Canal. The Defragmentation Notebook (Caiet de defragmentare) has precisely this purpose: to research into and to question the dominant narrative starting from the available information. The publication is of course also an art object, containing quotes, photographs, drawings, essays, punctuated by information from official sources. The publication’s jacket announces its distancing from the dominant discourse – a passage from a memoir denouncing the “murderous communist regime”[2] and the Canal, which “today lies abandoned and unused”[3] is titled Toxic Text. A comprehensive article by Ovid Pop then explains and refutes the assumptions from the fragments in the Toxic Text, making space for the complementary perspectives proposed by the various contributors to the publication: local and international artists, writers, and theorists. In this sense, the core of the project, Valentin Cernat, Ovid Pop, and Raluca Cotcoriciu, part of the team starting 2020, wanted a decentralization of the subject. The three did not seek to monopolize the discourse around the Canal, but to include as many views on the topic as possible, a topic that seems to be growing. Arhive-narative and Defragmentation Notebook were launched during two presentations, in Iași and Bucharest, where there were discussions around the psychological perspective on how the transition period affected the local population, accessing film archives from the Stalinist years, and, of course, inviting as many local and international experts, from fields as diverse as possible to maintain the voice of the Canal and to propose new perspectives on how we might approach it.

The Canal now has more than one voice, but what state is it even in? How functional is the Danube-Black Sea Canal in 2020? More than 35 years since its opening, traffic on the Canal has tripled, but it is far from reaching its full potential. Even though its infrastructure is fully functional and well-preserved, with public funds invested, the Canal seems to be in a latent state, waiting. As a property owner waits for an economic upsurge to sell an apartment, so the Canal seems to be held on stand-by in accordance with the state of the global economic apparatus. It seems to be waiting for the right moment to be used to its full capacity, but one can only speculate when that opportunity will come. A periphery that, like the Belgian canal, seeks to become a central node.

The constellation-project encompassing 4m3, Alternator, Arhive-narative, Defragmentation Notebook, as well as the numerous related exhibitions, interventions, and presentations, represents one of the most comprehensive and meticulous art-research endeavors in recent years on the local scene. But the project has long ceased to be a mere artistic approach, incorporating the historical and anthropological research work that local scholars seem to have abandoned. The uninformed digging performed by Valentin Cernat and Mihai Șovăială for D Platform 4 years ago unearthed an unseen part of Romanian history that could not be ignored.

This project, like many other socially oriented and investigative art projects from the last decade, is revealing for the Romanian people’s relation to its past. The generous contribution of local artists through relevant research and historical recuperations attests to the shallowness and disinterest with which the socio-cultural “legacy” of the communist era has been tackled by officials. If other countries of the former Socialist Bloc have been working since the ’90s on the recuperation, contextualization, and understanding of their recent history, as painful as the process might be, Romania seems to not be aware of how dangerous erasing collective memory is. This is why, 30 years after the revolution, the Danube-Black Sea Canal, together with other sites and topics from the same area of interest, need to be investigated and brought not just to the attention of the art world, but to that of the unspecialized, peripheral public at large. As Monica Enache, researcher and curator of the Romanian and Modern Art Department at the National Museum of Art of Romania, said in her excellent interview about the exhibition Art for the people? The official Romanian aesthetic of 1948-1965: “It can be a tough experience but, I think, a necessary one; we cannot hope for healing when we can’t even look at the wound.”

[2] Defragmentation Notebook, fragment from Toxic Text.

[3] Ibidem.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Marina Oprea

Marina Oprea (b.1989) lives and works in Bucharest and is the current editor of the online edition of Revista ARTA. She graduated The National University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, with a background i...

marinaoprea.com

Comments are closed here.