Sector 1 is one of the very few galleries that has inserted and provided a context for artists from the post-war generation, with an emphasis on the 80s, alongside their program based on current artistic production. Attempting a contemporary reevaluation in their retrospective exhibitions, they embraced productions that were most often singular in the context of the era, marginalized at the expense of what was accepted as official. An interesting strategy that I have noticed in the gallery’s program in the last 2 years, which includes this exhibition, is to have the artists still in the process of settling their discourse moved into institutional contexts and the already institutionalized artists or those “to be recovered” moved in the space of the private gallery.

Both producer and actor of some of the defining artistic manifestations of the 80s, seen today as provocative to the degree of subversiveness (due to the intervention of authorities on some of the actions/openings), Dan Mihălțianu is part of the second important category of Romanian postmodernism, alongside the dominant neo-expressionist branch, the intermediate trend in which he had Olimpiu Bandalac, Călin Dan, Teodor Graur, or Gheorghe Raszovky as practice partners – often collaboratively. He is an artist-researcher who equally plays the role of “producer”, “visitor” and “consumer”. Since the end of the 70s, the beginning of the 80s, Dan Mihălțianu defines a corpus of works that encapsulates in its center a rhetoric about the status of the artist in relation to artistic institutions and the condition of nomadism imposed by the context of globalization, and on a wider scale, about the impact of political changes combined with derived economic practices within the social context. This is achieved using the most varied mediums, such as photography, graphics, video, installation, etc., specific to an archival or “time-based media” type of practice.

The exhibition was contextualized and initiated following a dialogue with Mihai Pop and it will also benefit from a documentary support in the form of a catalog next year. It links all these concerns of an artist who in the last decade has been mostly present in an institutionalized context – meaning that the part of him which questioned the relationship with a central authority was affirmed and assumed, commodified through the most representative artistic product, the swimming pool-object of the “Canal Grande” series, which instead took on a life of its own through the willful adapting, or triggered by the context that it successively and materially added to itself, like a coat (is it like those floating on its surface, in this exhibition?), with each new space in which it was placed. By presenting a varied production made over 40 years, the exhibition manages not to fetishize this work again, which almost acquired, with or without the artist’s will, the value of a self-portrait.

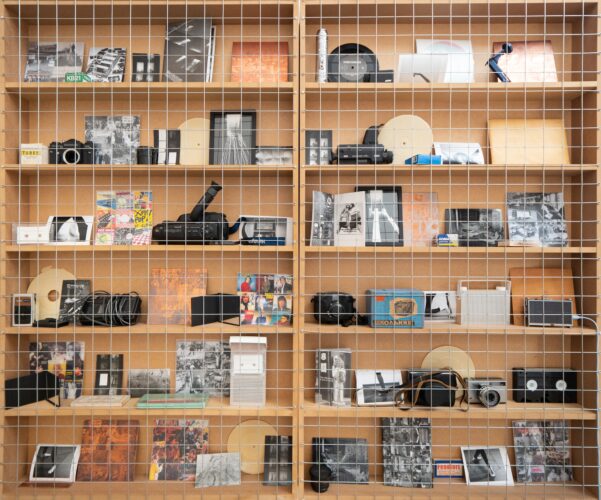

At the beginning of the exhibition route, we are guided by autonomous showcases, which contain either technical objects and documents of the era, specific to recording and archiving activities, or bottles with various products resulting from the “Distillates” series, as in a kind of artist vivarium. These two ecosystems function as two guiding poles: one shows the means by which documentation is achieved (techne), the other the process (episteme), while the distillation remains an operation of analysis and separation. Alongside them are photographs documenting burdensome installations on objects of common use, specific to the early creation, which guide our route through a narrow corridor into the main exhibition hall. Deliberately left in shadows, I consider this not only a technical solution to present the video installations inside the space as best as possible, but also a direct reference to the artistic beginnings of experiments with light in the dark interior of the attic-workshop, where the work “Canal Grande” takes shape for the first time in the year 1984 – coincidentally or not, the year in which the artist first reads the eponymous Orwellian dystopian story, transforming it later into a heterotopia.

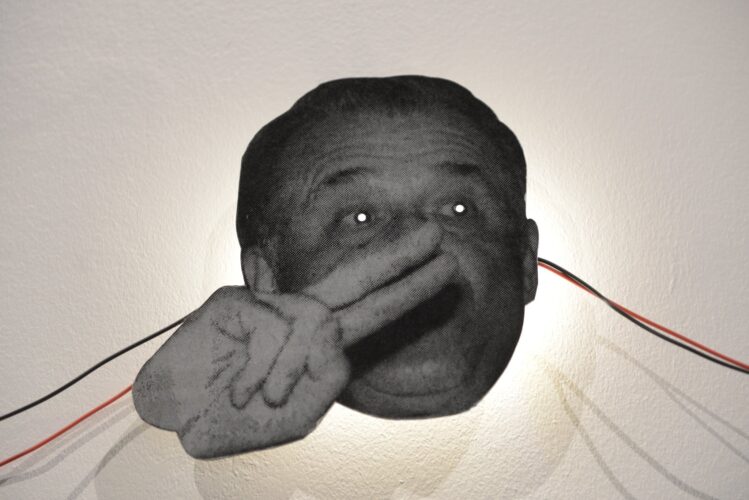

Inside the space, several of the installations specific to Dan Mihălțianu’s practice such as “Titanic Vals” (1986 – present) – part of the “Canal Grande”; “Last Days of Michael Jackson in Bucharest” (1992 – 2018); “Pocket Revolution” (1994-present); “Plaques tournantes” (2000 – present); “Totem” (2000 – present), are present alongside a selection of sketches, photographs, pictorial interventions or objects, outlining the totalitarian and descriptive notion of the skin of an artist, which supports this complex scenography. But this is not a Frenhoferian ivory one, but an open one, functioning in and for the interest of society more than in the attribute of soteriological self-mystification, to which the notion traditionally referred. Like this breathing organ, the artist’s skin can be found panoptically throughout the space, dressed by a recurring motif of the exhibition, the “studio pants”, or a nomadic artist, suggesting that Mihălțianu himself is somewhere between the walls of the exhibition.

I find this symbol of the trousers very candid and direct. It is seen as a pattern for the nomadic condition of the international artist today, so specific and biographical to Mihălțianu who lives between three cities, Bucharest, Berlin and Bergen. Ever since his first works that deal with this motif, such as in “Work pants on the front and inside out” one can see an interest in its singularization and objectification, both through the manner of hyper realistic representation, thus becoming – as in the case of the “pufoaica” – an archetypal artifact that perhaps is also part of a Platonic vision on the representativeness of the world. While we are referring both to the work that contains this second item of clothing, which dresses the upper part of the artist’s skin, as well as to Mihălțianu’s tendency to transgress an idea concretely and palpably (and later the “Canal Grande” even becomes an instrument for the transformation of material value into artistic value through collective participation) it is interesting to note how the chair (another central object of the artist but also of human activity in general), used in the photographically documented action “Dischair I-II” (1979) is the same as the one represented in the colored drawing from 1980 “Jacket on a Chair”, the artist thus demonstrating through the object-image relationship an active and integral consciousness. Perhaps it is not by chance that Dan Mihălțianu raised a Totem for them, considering both of its basic function of a connecting axis that vertically links the individual to the sky, and the fact that structurally it should encompass the entire material culture and moral values of a community. At the same time, clothing items in art tend to suggest the presence of the artist when worn by him, as I understand is the case with the vast majority of trousers that make up the totem, thus becoming another hallmark of the self-portrait.

The concept of liquidity as specific to the current social arrangement and performance, is a second motif that emerges within the exhibition. I will not discuss the similarity of vision between Mihălțianu’s artistic practice in relation to Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of “Liquid Modernity”, with the texts that accompanied the group exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 2019, curated by Cristian Nae, being more than relevant in this sense. I would like to mention that in addition to liquidity seen as the avatar of mobility and hyperconnectivity for the current world, the typology found in Mihălțianu is a lacustrine one, again of mirroring, springing from self-mirroring. The lake is as absorbing as the black mirror avatar of digital screens, implicitly contemplative. In the case of “Titanic Vals”, one can see how, after conducting light experiments on its surface, photographs that float as if in a developing tank, coins larger, and now it is the turn of clothes, consumerist “fluff”, to float on the surface, as if the work has exhausted its cycles, from q personal interventions in an attic, to the participatory and spontaneous use of the public – a pool/work that no longer belongs to the artist. On a formal level, the work shows a tension between art povera type materials from which it is formed and elements of pop culture that populate it, as Ileana Pintilie remarked since its first installation in 1986, when it contained pictorial accents and artefacts.

Between these accents that function as narrative signs in shaping the story, perhaps like the lizards that the artist had to hide through the titles and references of the works from the ‘80s, one can see speculative relationships between the “big” installations carefully placed in the economy of the exhibition space, which broaden their social and identity framework from which they often start. We observe, for example, how the “Canal Grande” mirrors the water of the Atlantic with its traditional port of entry for emigrants to the realm of absolute capitalism, thus becoming the “Titanic Waltz”. Also, “La révolution dans le boudoir” seems metaphorically caught between the concrete image of the American dream rendered in “Promise Land” and its simulacrum of Eastern ersatz version from “Last days of Michael Jackson in Bucharest”, leading to the thought of a staged revolution, in that the speech rendered with the help of the speaker seems all the more artificial.

The result is, I would say, an iteration of forms that index the multiple histories of their production, while simultaneously being sensitive to the current conditions generated by the exhibition.

The exhibition In the Skin of an Artist by Dan Mihălțianu, developed in dialogue with curator Mihai Pop, took place at Sector 1 Gallery in Bucharest during June 16th – July 30th 2022.

Translated by Bogdan Scoromide

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.