The exhibition “Muscle B(r)each” at Suprainfinit Gallery is a special kind of all inclusive Californian Wunderkammer despite the relative small number of exhibits: tribute memorabilia to the Light and Space movement and, in general, to west coast American modernist movements of the 1960s, reliquary for the new prosthetic sport accessories for augmenting body functions and the industrial materials easily adherent to skin surface, Silicone Valley childish enthusiasm and accessories from the surf subculture. Again, at a conceptual level, the exhibition brings together a cocktail of issues which do not avoid the new posthumanist hype around the body- technology- disembodiment debate and the prosthetic aesthetics rounded by the new (and predictable) affective turn.

The exhibition recalls into latent memory Muscle Beach Venice, the hangout of stars such as Arnold Schwartzengger and Hulk Hogan, which led to the popularization of the fit body culture, body building and Baywatch aesthetics. Since the name of no other than T e r m i n a t o r has just been mentioned, there must be added that the exhibition does not bypass the anxieties generated by such augmented specimens of the human body, envisioned here as hybrid-android assemblages, together with techno- colonialist frights of loosing the body through increasing technology empowerment.

The pastel metallic chromatic that seems to borrow from surfer girls’ candy glam is deceiving to say the least. As a matter of fact, the effect which adhered to my retina better than a hydrotransfer membrane is that of a high-tech designed gym, housing yet unclassified fetishes, and haunted by technocolonialist anxieties.

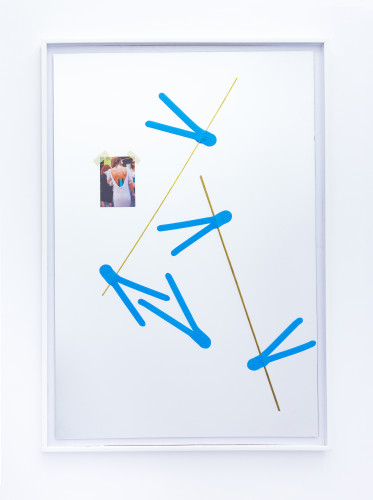

The fear that sport accessories could transform into fashion fetishes is present also in the exhibitional discourse which resemantizes, at an aesthetic level, the industrial technique of hydrotransfer and the usage of kinetic tapes. Sleek surfaces inspired by the oversized sculptures of John Mccraken and the frosted surfaces of Wayne Thiebaud induce a sensuous- sensorial response to the exhibited works which, in effect, seduce through glamorization. The exhibition is studded by dismembered limbs which allude to Paul Thek’s meat pieces/Technological Reliquaries although in here you must find your way out the aural seduction of the kinetic extensions in order to respond to them critically.

The exhibition suspends an undecided oscillation between a dot.com silicone idealism for possible extensions of man and a tentacular Crash! like fright for the outcoming mutations of man-machine breeding. As bystander, I found myself hobby-horsing conceptually between panic and enthusiasm, which, if I remember correctly, was very near the definition of sublime, in the most romantic understanding of the term. Techno-sublime and techno-colonialism represent, perhaps in their most summarized forms the constituent themes of the exhibition. The opening texts as well as the feminine limbs presented in the exhibition directs the reception of the exhibition towards an aesthetics of the prosthetic (Prosthesis Aesthetics) the newly found hype in the discussion surrounding the contact between body and technology. In particular against the background of new experiments with prosthetic limbs which already succeed in communicating with the body’s muscles and nerves.

The Prosthetic, understood as means to extend and re-functionalize an absent limb, is the often tense meeting point between biology and technology as McLuhan first pointed out. On one hand, the aesthetics of extensions identifies the prosthetic as being nothings else than a new fetish and a possible result of a physical or psychological trauma as presented in Ballard’s Crash! where the main character develops a morbid obsession (symphorophilia) for the coupling of dismembered human limbs and car wreckage during road crashes. Ballard himself saw man-machine hybridization as being the prime example of pornography and voyeursim which originated in self-disgust, infantile dreams, consumerist dreams and the death of affect. On the other hand, the Prosthetic aesthetics falls into a utopian dream of transcendence of body limits or augmentation of his preexisting functions. Is is in many ways what WIRED magazine and the Grindhouse Wetware project promote. Although they advance and support progressive fringe technologies they still remain indebted to pretty conservative creeds such as radical individualism and the idea of transcending body limits trough technology.

The inherent tensions of the exhibition translate, in effect, the existence of similar opposing directions in the new posthuman paradigm. For example, Carry Wolfe’s posthumanism insists on the acceptance of our biological limitations and the abandonment of dreams with cyborgs and terminators, which are, actually, nothing more than reminiscences of old humanist even religious illusions (accepting the body’s imperfections and finitudes and the desire to have experiences superior to those strictly bio-sensorial). Such direction does not admit, anymore, the idea of body dematerialisation. An oppositional direction had been articulated by Freud who thought of man as a magnificent prosthetic God and who had been hoping that new coming eras will bring even more awe-inspiring advances (as he was writing these lines, he himself was wearing an artificial denture-like prosthesis which he named the monster due to a cancer which was causing him tremendous pain). More recently, Stelarc, the ear on arm guy, advertised the entering of the cyber-zone through hybrid and surrogate bodies as the height of human civilization.

Hydrotransfer and Kynesiology tapes are punctual literalizations of the notions of depth and surface. The coupling stimulus- contraction inside the muscular fibre and the free nervous endings inside the skin structure conceptualize organic, natural and biological intensities. The electro-sensorial body responses are conversely redefined by the surface contact with these sports’ accessories. The master of surfaces, Lyotard, in the manuscript of his movie, “The Great Ephemeral Skin” envisioned these intensities as free-floating, impersonal and defined by a special kind of euphoria, one that lacks an emotional context. In between affect and surface takes place the alienation and fragmentation of the subject as well as an erotic tension. The euphoria of surface tension released by Adrian Dan’s cutouts is transformed into a fetishistic hedonism for human extensions through their glamorization into objects of desire and body beautification. Instead, the cyberpunk paranoia and eroticism survives still in the central piece depicting a surf board and an empty surf costume.

The sensual submersion of the hand depicted in the video installation as well as surfing on the membrane of the ocean delimit a surface tension both literal and symbolic. However, the adhesive liquid can quickly degenerate into verarophilia, the fetish and anguish of being ingurgitated by an alien aggregate. A shark, for example, prowling patiently and cynically around a surfer who swims unknowingly on the deep, dense surface of the ocean.

The intimate contact with prosthetic supplemental objects brings with it new uncategorized anxieties and fetishes. Their world is what Vilém Flusser described as vampyrotheutic. Prosthetics build self-referential systems which exceed man’s ability to decode them, although they became part of his body (through post-biological evolution) and had already modeled his cognitive processes. This way they transform themselves into a kind of Vampyrotheusis Infernalis, a gigantic underwater octopus, still hard to study and oversee, which haunts the depths of cold oceans. The expansion of prosthetic accessories can take tentacular and incrementally autonomous forms. In other words, what Catherine Hayles described as feedback loop phenomenons, those artificial systems which get to incorporate their own generative factors and delineate their own aesthetics- possibly superior to that of humans. She named this new aesthetics autopoesis.

Going further than a mere reference to John McCraken’s art or Californian modernist art, the surfboard placed in the second room of the exhibition, signals the absence of the body while the metaphysics of band-aid to which the exhibition alludes falls into an almost masochistic hedonism now that the dependency on artificial limbs becomes indisputable and fully acknowledged. The interaction between human muscles and synthetic fibres in the same way as the one between smooth pellicles of industrial compounds and bioderma, generates new forms of unclassified experimental relationships that delimit new areas of intensity, codified here as being erotic or affective. Virtually, the affect is redirected towards the non-human, most of all, towards the body augmentation devices.

In “Curie’s Children”, Vilém Flusser wondered why is that dogs aren’t yet blue with red spots and horses do not irradiate in phosphorescent colours over the nocturnal shadows of the earth now that molecular biologists could handle colours the same way as painters handle oils and acrylics. Not only would the landscape become more colorful but an even more crucial goal would be met: that of helping man to evade his own boredom. If only we would manage to accelerate the artificial. Kinesiology tapes and hydrotranfer patterns succeed in just that.

For those who (do not) want to engage themselves in endless discussions of the techno-euphoria vs technocolonialism, pornography vs sublime sort, the exhibition could be experimented as pure immersive spectacle of transparent, translucent and reflective surfaces as in the monumental sculptures of McCraken.

The Exhibition “Muscle B(r)each” is at Suprainfinit Gallery between March 18 – April 1, 2016.

Artist: Adrian Dan

With a special intervention by Pierre Alexandre Mateos

* All Watched Over by machines of Loving Grace is the title of a series of BBC documentaries directed by Adam Curtis.

POSTED BY

Georgiana Cojocaru

Georgiana Cojocaru is an art writer, curator and editor living and working in Bucharest. At the moment, her research practice focuses on generic aesthetics, poetry in the Anthropocene and fictionalisa...

1 Comment

very funny