Sabina Suru is an intermedia artist and cultural manager based in Bucharest, co-founder of the Marginal Association and the artist-run hybrid VAGon – an (inter)disciplinary space within the Malmaison Workshops. With roots in painting and argentic & alternative photography, her practice manifests itself through various intermedia approaches – interactive or participatory installations, holography, objects, photography, or film. Her works address issues related to the mutation of object and media identity, digitization and exographic memory, care for technology, and alternative human and more-than-human relationships with technology, through collaborations with other artists (choreographers, performers, musicians, visual artists, and artisans) or researchers in science and the humanities.

You trained as an intermedia artist and are passionate about the history of technology and science. How did you get from art to science?

My artistic journey includes painting, photography, and argentic and alternative holography, video, and installation, brought together in a post-digital approach. My interest in science has always been present and has naturally integrated itself, little by little, into my practice, without necessarily feeling like a leap at a very clearly defined moment. I would say that it was (and is) rather a slow and iterative expansion of my tools for exploring reality. Although my training is rooted in fairly traditional media and approaches, I have never navigated them with ease, but rather with a kind of patience. I was very motivated to study art, and the fact that our school persists in approaches that no longer make complete sense was not enough to demotivate me. We could say that I endured the traditionalism of my training as an artist, while systematically turning my attention to technique, to the history of technology and the reciprocal relationship it has always had with the history of culture and art (one of the few teachers I admired during college always told me that I was a “technician,” which I took as a compliment :D). This “technicality” inevitably led me, over time, through various branches of technology and science – first, through the natural connection with the evolution of technology and the arts, then it became an interest in its own right through the practice of photographic and holographic laboratories (where it would be difficult to navigate without some knowledge of chemistry and optics, for example). There is also a reason closer to my human roots as to why I am attracted to objects, technologies, and their forgotten stories – I grew up with two brothers who were equally attached to abandoned technologies. We were largely self-taught in understanding and approaching the things that interested us from an early age – for them, electronics and computers; for me, optical assemblies and technologically mediated art. I believe that reevaluating old technologies and techniques and their dialogue with new ones generates innovation in technology, science, and art, and discreetly participates in various forms of hybridization and continuous remediation.

So you have a soft spot for environments that bring together, in a unique way, dissociated fields. What motivates you in your work as an interdisciplinary artist?

My motivation comes from my belief that innovation arises organically at the confluence of the old and the new, at the margins of seemingly separate fields; just as, looking back, we can find new ways of looking forward. I am particularly interested in how technologies and techniques, both new and old, shape our identity dynamics. Building on this difficult-to-quantify relationship between the new and the old, through a continuous dialogue between applied arts and scientific practices, I want to create experiential, participatory spaces that activate both emotion and critical thinking and challenge the public to actively reflect on the relationships we build with technology.

What role does the artistic object play in your work, and from what other disciplines do your working tools originate?

I ended up studying painting as a result of a series of coincidental circumstances (one of the most successful accidents in my artistic career). As I gradually assimilated it, I realized that it is one of the most versatile creative fields (unlimitative is the word that comes to mind when I think of painting, but unfortunately it does not exist in the dictionary). This does not mean that, in practice, it is not often constrained, especially in school. Once I started exploring alternative photography techniques (which share a lot of tools with painting), objectification, literally, was a step that seemed not only necessary but also obvious, which quickly and irrevocably took me out of the two-dimensional realm. Being self-taught in photography, I relied heavily on experimentation and information found in old books on technique, history, and theory of photography, which inevitably led me to argentic holography (and implicitly to chemistry and physics), biomaterials, other imaging techniques and technologies, and, of course, I ended up in numerous fragile areas of technology, where I began to tentatively explore various contradictory ideas that I stumbled upon, related to technological heritage and new media conservation, theories of care and ethics, ontology and technological taxonomy, biotechnology, objectification, inter- vs. trans-disciplinarity. These explorations, which are at the root of my practice, also participate in a very complicated dialogue with the art scene, which is still dependent on media-based navigation.

Paradoxically, you revalue old technology, but you have come to train machine learning algorithms for your projects. How did you manage to create a creative dialogue between the old and the new?

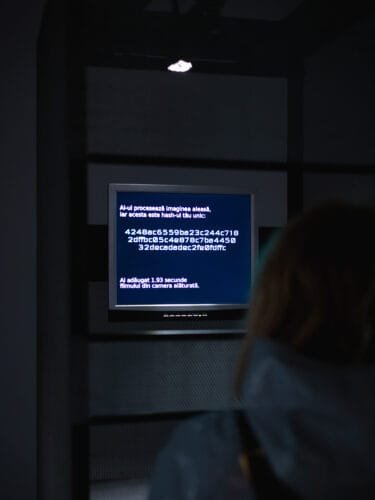

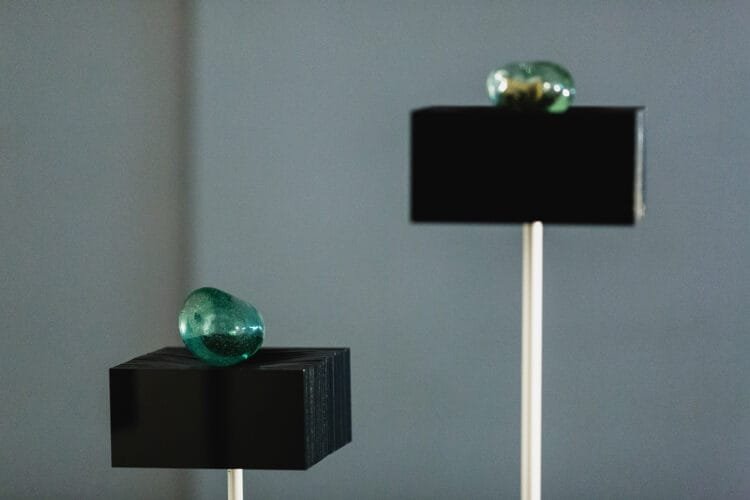

I don’t feel that there is necessarily a contradiction here. This dialogue between the old and the new seems to me to be a natural source of innovation and knowledge. For example, in the project The Entropist, I explored the human relationship with technology using machine learning algorithms to analyze and transform certain aspects of digital identity and the lack of accountability in relation to them. Two years later, in 2024, I was working on Persistent Objects, in which I questioned certain aspects of the identity of abandoned technological objects and the lack of human responsibility in relation to them (and the inherent ecological implications). This time, it was a non-participatory installation, in which the 20 objects in the installation no longer served any purpose for human comfort; they were passive, covered by an organic medium that mimicked a paradigmatic care that they did not receive and did not seem likely to receive anytime soon. These are different approaches and questions related to different types of identity, but essentially subordinate to the same question: why do we, as a species, manifest our self-assumed supremacy through consumption and abandonment, instead of caring for the eco- and technosystem of which we are a part, and which we (re)create and shape every day?

In your work Faulty Technology, your creative process was stimulated by printer errors. What role do accidents and errors play in your work?

In Faulty Technology, I explored visual mutations based on technological errors and accidents (leitmotif, leitmotif). For me, error is not a failure, but a catalyst. It is a way of challenging the proverbial quest for technical perfection, which I find limiting in the digital world (not just in the tangible one). I strongly believe that it is precisely through technological defects, through the accidents that I integrate into the process, that I can reveal another facet of reality, one mediated perhaps precisely by the vulnerability and imperfection of technology, which mirrors the human one in many ways.

You want art to become a medium for dialogue, not just for communicating the artist’s emotions, and your installations are interactive. What attracts you to subjective engagement with technology?

I am interested in my works provoking the audience to take an active position, to go beyond speculative or formal contemplation. Equally, I want to integrate them into my research and creative processes. There is a cultural bubble in which we swim and from which we cannot hear or see many things that are happening in the world around this bubble. An active relationship with the audience can make a contribution that I find essential to the questions I try to raise through my practice. That is why many of my installations are interactive or participatory, and in the last 2-3 years I have frequently included work-in-progress stages in which feedback from audience participants has been essential to the direction or form the work has taken. Equally, I do not see technology as a mere tool. Technology mediates and alters my perception of reality, of the body, of the image – a game in which I invite the audience to become participants.

You enjoy challenges, difficult work processes, in which you show dedication, stubbornness, endurance, and patience. What has been the biggest challenge in your work so far?

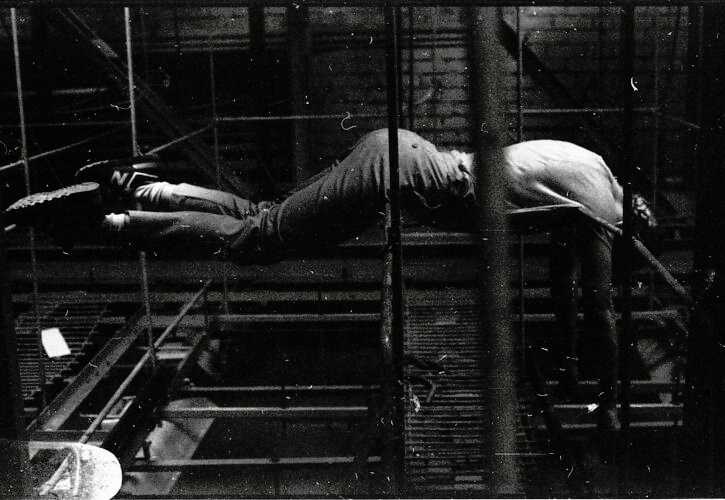

I do indeed love slow and iterative processes. Modular working techniques, with many stages and layers, transport me to a very creative and emotionally restorative mental space. I think it has more to do with my temperament than with my artistic approach. In painting, I worked in the same way, in dozens of layers of transparencies, contrasting with areas of raw materiality, over which I then added more layers. From there, I approached other techniques and technologies, but essentially the tinkering remained. About eight years ago, however, a change began in my way of working when I was invited by Alina Ușurelu to participate in “Exposing Movement,” where I worked collaboratively for the first time with people from the contemporary dance field. Then there was another change when I started to give more weight to research (rather than exploration, as I had done until then), which meant investing much more time in the theoretical part and in the way it underpinned the experimental part, long before actually creating the works. These were new stages that were inserted into my work process, which greatly reduced the time invested in the manual part of my work. I am still in this period of adjustment, which is much longer and more uncomfortable than I expected. Not so much because I have less time for tinkering, but because I enjoy the theoretical digging into history, science, technology, and philosophy just as much, bringing them together and experimenting with the edges of all the areas I was working with before.

You are completely immersed in the process, truly enjoying the time spent between clarifying the idea in concept and the result. You are also energized by connecting with an enthusiastic audience to experience reactions and sensations through dialogue and interaction. Does the process keep you in a childlike state or that of a magician?

I really love the process – from reading and digging into theory, to heated and confusing discussions with researchers from various scientific fields, to transforming the workshop into a hybrid halfway between a carpentry workshop, photo lab, construction site, and kitchen. From there, jumping a few steps to the part where I talk to people who come to the exhibition, who always have the most disarming questions, I arrive at another place that is just as wonderful (and uncomfortable). I think it’s vital to build this process with a lack of preconceptions bordering on naivety, in a childlike mental and emotional state that doesn’t judge, with a mind and heart full of “whys.” Regarding the other side, that of magic, my mind instantly flew to the third of Clarke’s Three Laws: Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

In addition to your artist’s hat, you also wear that of cultural manager, as co-founder of the Qolony, Allkimik, VAGon, and Marginal initiatives. How do you juggle them and what do you bring from one field to another?

All these experiences you listed slowly but surely led me to Marginal, which I started in 2022, together with Andrei Tudose. I thought of Marginal as an interdisciplinary (and, we hope, in the not-too-distant future, transdisciplinary) platform to bring together artists and agents from other fields of research to explore the implications of science and technology in social-cultural, human, and more-than-human structures alike. It sounds complicated. And it is, because bringing together things that are not used to being together is neither quick nor simple. But I am patient. This juggling act between being an artist and a cultural manager is also complicated at times (they are practically two interdependent jobs), but they support each other, because the research I do as an artist almost always branches out into areas that are also necessary for the association — such as technosystems and technodiversity and their impact on natural ecosystems, the loss of techno-cultural heritage and the redefinition of relationships with technology, or how truncated methodologies of collaboration affect both research and creation or public dialogue. Before Marginal, Allkimik (2022-2024) and Qolony (2019-2022), as well as the hybrid artist-run space VAGon – in(ter)disciplined space (2021-2025), within the Malmaison Workshops, are still dear to me, but they are now more a part of a formative past.

You feel most at home in the studio, “as an extension of the inner, emotional, and rational space.” Last year, you had a long-term residency at the Cité Internationale des Arts. Did you feel at home there, or did you transform the space according to your needs?

The residency at Cité came at a time when the studio where I had been working for more than 10 years was (once again) in question, returning to a cyclical state of temporariness specific to that building. At the same time, last year, through this residency, it was the first time in my career as an artist, for whom theoretical research is an essential starting point, that I was able to sit quietly for three months reading, walking the streets of a new city thinking about what I was reading, roaming bookstores, and leisurely jotting down ideas and working hypotheses for the next stage. The space where I was in residence was far from being a natural workspace for me. I am used to spaces that could be simplistically described as dens – small, intimate, dark, full of things and books and pieces of work packed up to the ceiling. Here I was welcomed into a large, bright, minimalist space with a glass wall overlooking the Seine, from where I could closely follow the progress of the reconstruction of Notre Dame Cathedral. It was three wonderful months of burying my nose in books, seeing things I had rarely had the opportunity to experience in real life, and meeting incredibly diverse artists (from a sculptor who worked with cement to a film animator who worked on greening practices in cinema, to composers and organists).

What project came out of this residency?

Since it was an artistic research residency, the process was kind of reversed – the project came before the residency. Once I got there, I quietly worked on the first stage of research for the Persistent Objects project, which was also the basis for the artistic direction of the Places of Care project. But it is true that, without a prior plan, a new project did emerge, because the Cité Internationale des Arts hosts dozens of artists at the same time and it was impossible for some ad hoc things not to happen. I met a number of artists and theorists from all over the world, whom I invited to take a closer look at the norms and vices of inter- and trans-disciplinarity. The result was the project 3’17’’, a critical and satirical approach to the excessive use of buzzwords and the neglect of omnipresent elements in the cultural field, such as precariousness, dysfunctional collaboration, or the truncated definition of essential terms in emerging fields. This year, we are returning with it to Paris, where we will give a site-specific presentation of the project at The Film Gallery, which I am really looking forward to!

What new projects are you involved in now?

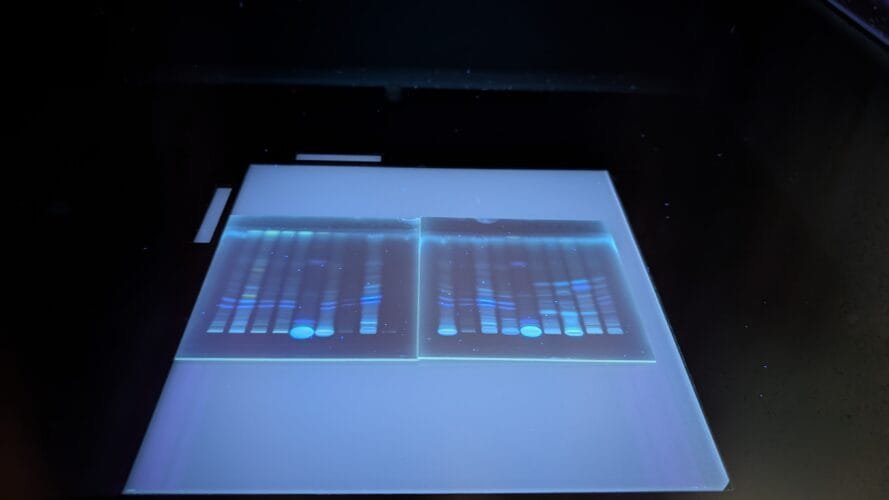

This year has brought a lot of new things for me – I am among the artists in residence at the Bucharest Institute of Biology of the Romanian Academy and 2Celsius, as part of the Otherwise Residency program, in which we collaborate with researchers on projects developed by the institute. I, for example, am a resident at the Department of Microbiology, where I work with two very cool people, Dr. Simona Neagu and Dr. Mihaela Stancu, on an analysis of the biotechnological potential for remediating environments polluted with hydrocarbons (compounds from oil processing) using indigenous halophilic bacteria collected from the Prahova area, from soil, sludge, and water. This is the first time I have been so close to the living environment, and as spectacular as the research processes, tools, and highly ethical approaches I have happily found in the paradigms of the researchers I collaborate with at the institute are, I spent a long time in a state of amazement and fascination, trying to navigate an enormous amount of new information that seemed far removed from my field of study. However, as I spent time at the institute, it became increasingly clear to me why I was there – through many discussions with Simona and Mihaela and the time spent in the laboratories, the extent of technological advancement in microbiology research processes became evident to me, step by step, layer by layer. In order to isolate the identity of a bacterium, there are dozens of approaches and stages, guided by protocols, interpretation conventions, or identification through numerical compatibility in global peer-based databases, aka interdependent technologies and techniques that involve accepting many ambiguities at each of these steps. I then found myself reading about the linguistic similarities and differences between science, art, and media theory. The term “remediation” itself has fundamentally different meanings in these fields, but it clearly isolates some forms of semiotic ambiguity. Now, in June, we are entering the second stage of the residency, in which I will again spend a few weeks at the institute observing other layers of their research processes, and I will be able to bombard them with questions about the identity and behavior of some of the most extensive natural ecosystems (microorganisms) and how much they condition the mediation (and remediation) influences how they are perceived in the cultural and vernacular space.

Later this summer, I will be attending another residency that I am very excited about, Heritage First!, in Băile Herculane, where I will have the opportunity to research aspects related to the technological heritage of water extraction, its implications for the dynamics of this area, and the use of old technologies in everyday life.

Also, as I am answering this question, I am in Timișoara, on a mobility scholarship from the Project Center, where I will be part of numerous discussions with organizations I care about here (Simultan, Indecis, etc.), in order to set up some projects and collaborations in the coming period.

You are interested in the unclear connections that push culture in one direction or another, and your artistic approach revolves around ideas related to identity, control, and technological instrumentation. Where do you think culture is heading in the age of artificial intelligence?

It seems to me that we are going through a repeat of a similar dynamic from the beginning of the industrial revolution, in the sense that technologies have become accessible that renegotiate the relationships we have socially, professionally, humanly, and more-than-humanly, which is not a bad thing. However, I don’t think that graciously and patiently accepting change has ever been a human quality. On the other hand, looking back at all the changes generated by each technological leap (we are, theoretically, now in the midst of the 4th technological revolution), we are heading in the right direction, provided that we start looking at the impact we have on the eco- and techno-systems with which we exist, accept the consequences of this impact, and shift some paradigms. I naturally lean towards optimism, but now, in the midst of the changes that are taking place before our very eyes, we are only moving towards the better if we begin to assume the responsibilities that come with being at the top of the food chain.

In the installation presented by Marginal last year at the Simultan Festival in Timişoara, 3’17”, I listened, among others, to artist and theorist Lev Manovich talking about his pleasure in working with technology to facilitate his artistic processes. What is the artist’s responsibility in his relationship with technology?

I believe that we must first define the human relationship with technology, which would inevitably redefine mediated and unmediated identity (if the latter is still possible), intelligence, and cohabitation, both with technologies and with other living species. But limiting ourselves a little more realistically to artistic responsibility – I have always advocated for the acceptance accident and serendipity, the coexistence of the old with the new (which is not limited to technology), or the fact that the individual authorship of the artist is impossible when it comes to interdisciplinarity and working with technology, which, although a gentle and cooperative collaborator, must be perceived and assumed as a collaborator, not a passive instrument.

We met at the SIMULTAN Festival in Timişoara, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this fall. How did you perceive the festival at first contact?

Weird music, as a very nice person I recently met calls it, has been one of my passions since adolescence. When I started college in Bucharest, I suffered a little from the absence of people interested in experimental music, post-punk, and other music that was like air to me. The group of friends and acquaintances with whom I could share this interest consisted only of Floriama and a couple of other friends. There were two oases of joy, however – Sâmbăta Sonoră and SIMULTAN Festival. I never missed the former, especially during the time it was held weekly at CNDB. Inexplicably, I didn’t get to SIMULTAN until 2021 (but I followed it passionately, from a distance, year after year). And then I arrived as an artist, not as a spectator. SIMULTAN has another very special quality in my inner world: it is a festival that, after 20 years (!!), is still driven by passion, organized by a small team, in an intimate and genuine setting. Since 2021, I have been attending every year. Now I couldn’t imagine life any other way, and each time I enjoy the musical and artistic selection as much as the wonderful people behind the scenes.

How has your collaboration with SIMULTAN evolved over time?

SIMULTAN is directly responsible for the fact that I am no longer afraid to exhibit in large spaces. In 2021, when I went for the first time, I brought Particule afective to the festival, one of my first collaborative projects in which I tried to bring together a seemingly bizarre combination – argentic holography, contemporary dance, and quantum physics. It was also the first time I worked with a researcher from the scientific field. It was a difficult and wonderful project, and I am very glad I had the courage to do it. Returning to SIMULTAN – it was the very beginning of the year and we were just preparing the project, hoping to find a source of funding to bring it closer to reality. Irina Marinescu, my fellow choreographer on the project, suggested we take the installation to SIMULTAN. A few months later, the project was happening and we were preparing to leave, with a plan made down to the smallest detail: where the windows are in the Garrison hall, how and with what we cover them, how we wire them, how we hang the holograms. Two weeks before the festival, however, we received news from Alin Rotariu that the entire festival was moving, with us of course, to STPT, where we had the choice between a 200 sqm hall and a 300 sqm hall (Andrei Tudose, who was the curator and my pillar of strength in the project, had just managed to convince me that 100 sqm, which is what we had at the Garrison, wasn’t that much). We rearranged everything on the go, us for Particule and the SIMULTAN team for the rest of the festival. I still remember when I first met Alin face-to-face: we arrived in the STPT courtyard, I called him, and he guided us to the middle of the courtyard, which was littered with trams and cranes. And there he was, in the middle, calm and smiling, gracefully directing the distribution of the trams, so that five hours later, the courtyard was completely clear. When I saw the space (I opted for the 200 sqm one), I fell in love and was terrified at the same time (haha!). I reconfigured the entire installation, physically and choreographically, in situ, during the two days of assembly. I don’t remember ever being more scared that we wouldn’t be ready in time than I was then. But everything turned out perfectly! Now, I calmly arrive 1-2 days before the festival, knowing without a doubt that everything will be okay, with the SIMULTAN team by my side. It’s refreshing to go once a year to set up an exhibition without fear, knowing that any unforeseen circumstances will be met with humor, relaxation, and creative solutions that really work.

What does the SIMULTAN Festival mean to you?

It’s a kind of home away from home, not only emotionally (although it’s a nourishing place for the soul, not just culturally), but also professionally. I somehow find balance in it as an artist – if my work isn’t included in the festival, I wonder if I’ve done something wrong. It hasn’t happened yet, in five years, so everything’s fine. 🙂

The theme of the SIMULTAN 2025 festival is Re-Mediate. As this is a theme that is dear to you and that you are already working on, what is your relationship to the concept of re-mediation?

For me, remediation is an essential analysis of how information, memory, and experience are transformed and reinterpreted through other technologies. It is a process of transformation, reinterpretation, and recontextualization, central to my practice, intended to generate new meanings and new modes of perception. Over time, I have explored different facets of this approach. Faulty Technology is an example that naturally comes to mind. The work highlights the inherent vulnerability of technology, an aspect often ignored or overlooked in our digitally dependent society. It is proof that even dysfunctionality can become a starting point for a new form of expression, an awareness of both electronic and digital fragility.

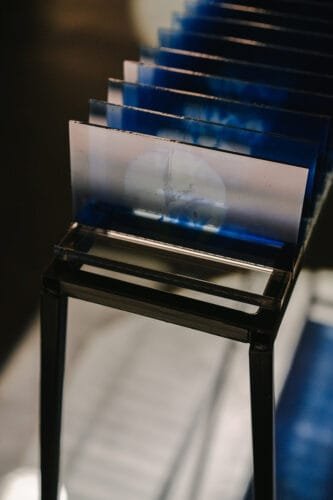

On the other hand, in The Blue Room, the remediation went in a different direction – here, the digital medium is translated back to the origins of photography, through cyanotype on glass. This move is not only technical, but declarative: the digital image is objectified, made tangible, in order to assume a manifestation of remediation that I find very important: hypermediality, an essential concept in media theory, of assuming the medium itself, the interface. I wanted to draw attention to the palpable presence of the medium, inviting the audience to experience not only the content, but also the medium itself, which is an integral and presumed part of the system.

What might the SIMULTAN festival look like in 20 years?

Lively and wonderful, for sure. One of the things I have always loved about SIMULTAN is that it does not limit itself, it does not fall into the comfort of inviting the same people over and over again (except for me, I hope), but constantly looks beyond itself, always brings in interesting artists, and offers support to young artists, indiscriminately.

Translated by Marina Oprea

POSTED BY

Maria-Luiza Alecsandru

Maria-Luiza Alecsandru is a cultural journalist through training, curator and cultural mediator through adaptation, author and artist through passion. She works with video, installations, photography...

Comments are closed here.