Ah, another day, another art show that questions the notions of time, space, utopias and capitalism within the ever expanding paradigm of contemporary life. Capital’s Time Machine opened last week in Bucharest, hosted by Beans and Dots at Apollo 111, through the efforts of Craiova’s Club ElectroPutere and The Real Office of Stuttgart. However, this exhibition is quite unique, because the works by artists Silvia Amancei & Bogdan Armanu (RO), ALB (RO), Lörinc Borsos (HU), Mihai Iepure-Górski (RO), Tatjana Macic (RS/NL), Andrei Nacu (RO), Astrit Ismaili (XK/NL), Kestutis Svirnelis (LT/DE), Johannes Hugo Stoll (DE) and Taietzel Ticalos (RO) are not displayed within a gallery. In fact, the entire show consists of a vending machine containing condensed versions of the artists’ pieces in neat little boxes, a kind of Boîte-en-valise with a capitalist twist: you have to pay to see what’s inside.

So here we have it, a compact art exhibition that requires no space, no set-up and no gallery custodians, which can be easily moved from place to place. It did, however, require not one, but two curators to come up with an elaborate yet vague curatorial discourse about temporality and economic exchange, select the artists and recontextualize their works so they might fit, even if only marginally, with the overall theme. The vending machine is, in itself, a nice touch, an eloquent metaphor for the way in which artists make a living nowadays: you might never sell your art, or you might sell it to someone who isn’t even aware what they’re buying.

The idea of a cultural vending machine challenges conventional views on visual art and the art market, putting art to the money test: the works are sold at low prices that are very affordable for potential buyers, but would only cover the production cost, at best, for the artists. It also eliminates the middle man from the entire transactional process; no galleries, institutions or art dealers are involved. And the fact that the works are hidden from sight implies trust and/or documentation on the buyer’s part, essentially altering the viewer’s passive role, who must now act in order to have access to art. The vending machine is an excellent concept that can be read on multiple levels, and it can also serve as a test to see how invested the public is in this very particular brand of art consumption. Yet the curatorial text and the selection of artists don’t quite align with all these notions, indicating to something else entirely. There is no mention of neither the transactional aspect, nor the concept of an unseen work of art anywhere in the printed art statements. Instead, the whole endeavor was dressed up in the all too familiar garments of speculative concepts that are safe and ambiguous enough so that they cover all bases, at least on paper, almost as if the curators were afraid to own up to their true intentions.

Potential buyers weren’t totally left in the dark. There was a presentation during the opening evening, so that artists got to offer a little glimpse of what their box might contain, but only a few of them actually showcased their project.

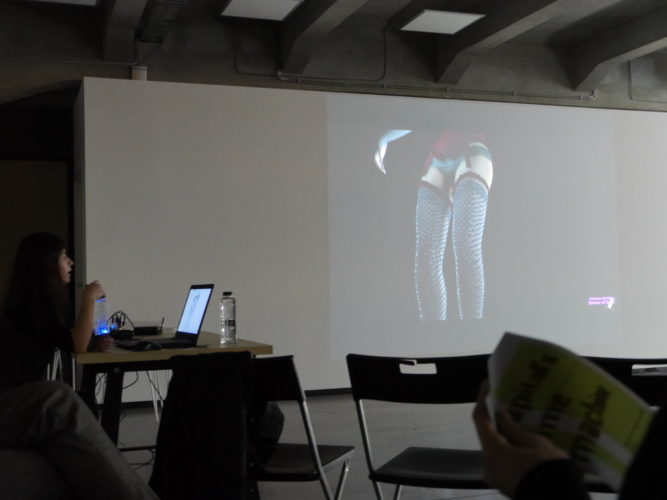

Out of the presentations, the only one that truly aligned with exhibition themes was Taietzel Ticalos’s project around findom. In the ever growing online world of sex work, findom or financial domination is a fetish of power exchange which involves the transfer of money from sub to Domme as an act of ultimate submission, as money is the ultimate representation of power in our modern society. Taietzel however, took it to the next level and created a virtual avatar for her dominatrix persona, in an attempt to see how far can real life be transmutated to the virtual sphere. The most interesting aspect is that her practice is not just limited to the art world; the 3D figure is actually active on various fetish sites and has real life subs who worship her. However, the artist always remains unseen, hiding behind an avatar and never showing her face to the public, not unlike the boxes inside the vending machine.

Similar to this approach, performer Astrit Ismaili challenges notions of family, gender, sexuality and identity and the normative models of mainstream media that establishes and reinforces them. For some time now, he’s been working on a character which has already made appearances in performance pieces, fashion shows and even concerts: a pregnant male. Inspired by the image of seahorses, one of the very few species in which the father carries, develops and gives birth to offspring, Ismaili’s take on the exhibitional theme is fluid, not just gender wise, but also in terms of temporal realities. His unnamed male figure with child hints at characters from Greek Mythology. Ismaili and Taietzel weren’t the only ones to present piece that expand beyond the boundaries of art, yet none were as far reaching.

Tatjana Macic is a visual artist, writer and researcher based in Amsterdam, whose work focuses on the intersections between art, theory, language and education. For Capital’s Time Machine, she approached history as a medium that can be shaped, choosing to alter the narratives of her grandparent’s lives: a man who became the hero of his hometown and is celebrated today, and a woman who was lost in the sands of time. An all too familiar approach in contemporary art and one that seems to be very anchored to a certain area for a project that aims to deconstruct space and time.

So familiar, in fact, that Silvia Amancei & Bogdan Armanu, Iași’s rising artist duo, also presented something along those lines. During their slot they showcased in full their latest short documentaries about their respective families’ means of earning money after the fall of communism in Romania. The stories themselves were engaging and funny at times, yet it feels as though this formula has been over and done, especially in the Romanian art scene: a slice of life documentation of more or less conventional lifestyles from a particularly tumultuous historical era – commonplace and a little bland for locals, but very exotic for the west, I would imagine. It’s been going on for ages, yet it never seems to lose its allure, so much so that these pieces hardly seem to have anything to do with art anymore. Amancei and Armanu’s videos could just as well be a journalistic investigation; it says so in the artists’ bio.

But I suppose this is what this show is all about: displacing as many elements and concepts to see how far this could go. The present is either reminiscing the past or dreaming of the future, utopias are no longer separated by space, history is not an immovable entity, art is no longer (just) art, but a commodity. Some of these repositionings worked better than others.

ALB (Andreea-Lorena Bojenoiu) added a rather formal piece to the vending machine, a series of performances very similar to Saburõ Murakami’s 1956 Laceration of paper. This work did not need a presentation, really, it was already presented before in multiple venues, including The Museum of Contemporary Art in Bucharest, as well as various art publications. The artist carefully rips and tears a material from the wall as she attempts to pass through it to the other side. It’s a cute study on the concept of image outside of representation, yet it is a little unconvincing as far as it relating to any of the show’s themes. The printed art statements did, however, clarify that ALB’s performative reflection on image is linked to how images nowadays are strongly marketed and digitalized. A bit of a stretch…

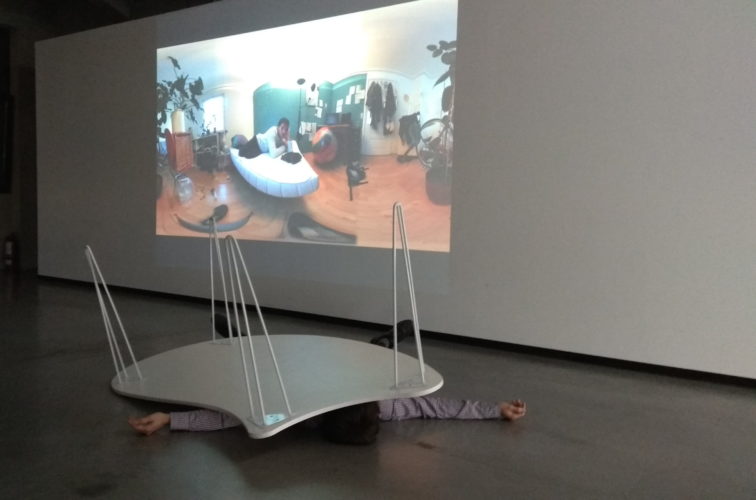

Speaking of stretches, German artist Johannes Hugo Stoll also investigates socio-cultural representations and how they affect the individual. His contribution to the vending machine is a video performance piece that is all about expansion. He filmed himself in his room with a 360 degree angle where he recited dates from the future in a chronological order for two hours. Stoll played a few minutes of his video, in which he attempted to encapsulate space and time within a self-contained and intimate setting. It’s a clever project, yet somewhat facile when it came to execution. But during his presentation, Stoll also engaged in a small performative act using a nearby table, hinting that his box in the vending machine might contain some hidden insight.

The rest of the artists involved in Capital’s Time Machine weren’t present to talk about their boxes’ contents, leaving the exhibition’s leaflet as the only clue to what might be inside. What is certain is that all boxes contain objects such as prints, collages or small paintings along with flash drives or links and secret codes to access websites and virtual tours. The price for a box ranges from 100 to 150 RON (the equivalent of 25-35 euros) but it is unclear what happens with the money. Are they reinvested in future projects or do the artists and curators pocket the cash? Only time will tell… As for the viewers, only someone willing to pay up can glimpse any and all artworks, but the pieces are theirs for the keeping.

Update 14.11.2018: After this article was published, Club ElectroPutere’s Facebook page posted photos with some of the art objects in the vending machine.

Capital’s Time Machine can be accessed at Beans & Dots – Café, Palatul Unviersul until December 30th

POSTED BY

Marina Oprea

Marina Oprea (b.1989) lives and works in Bucharest and is the current editor of the online edition of Revista ARTA. She graduated The National University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, with a background i...

marinaoprea.com

Comments are closed here.