The intersection between art and technology has lately become one of the most explored areas of interest throughout the great art spaces of the world. And as various initiatives have recently taken off, such as spam-index.com, the first Romanian online platform to focuses on digital/internet/post-internet art, the local art scene tries to align itself to international standards.

Half a century ago however, this area was largely unexplored, and the American artist with South Korean roots, Nam June Paik, considered to be the father of video art, undertook this pioneering work. For centuries, art and technology have been seen as being two separate, even divergent, entities, but in his essay “Media planning for the post industrial society”, Paik promoted the idea that technology would become commonplace in people’s lives, and predicted that the future will be connected, hinting at internet, calling it back then the “Electronic Super Highway”. However, he did not have in mind a distant future described as in a SF book, but rather a near future built on human basic needs.

The interactivity and connections created by technology represent a major change brought on by new media art (video art, digital art, interactive art, virtual art etc.) in the traditional context of art spaces, where visitors are rather passive observers who are quietly gazing. But now, with technology’s “monopoly” of art, people can interact with the artistic product, play with it and even possess it, a phenomenon for which the Romanian neo-avangardist artist Paul Neagu pleaded in his Palpable Art Manifesto. Back in the 60s (when it seemed like the world was in need of an urgent art revolution) Neagu declared that “the eye became fatigued and superficial”, striving for more than just one kind of visual art. “Let there be one type of art through which all senses, sight, touch, smell, combining each other so that one can possess the object in every sense”. Neagu invited the spectators to open the drawers of his work and see what awaits inside, to touch the artwork and to eat the cakes after the performance ended (Cake Man).

The Wrong Biennale #4 “is the largest decentralised art event” because it takes place both offline, in institutions or art spaces in cities around the world, and online, on thewrong.org, where the works of various artists can be seen. The Bucharest exhibition reflects upon technology and its impact, as well as upon the new trajectories within the field of art which goes even beyond this sphere.

What is wrong with the artworld(s)? – the question behind the exhibition’s curatorial concept aims to explore the im/permeability of media art, to define the artist’s and spectator’s role, as well as that of technology in art, questioning even the act of creation (Was it created by humans or generated by a computer?). The exhibition launched the challenge, both to artists and spectators, in order to identify the present errors in the artworld. As it was expected from such an event, the visitors could interact with the artists’ works and explore virtual realities. HanHana, created by Melodie Mousset, takes the spectators on a surreal journey where they can teleport themselves and expand their own bodies. Sentientia by Dorin Cucicov is a sound installation which distorts emotions. This complicated mechanism, an amalgam of prehistory and postmodernism, records environmental sounds and tries to determine the emotion they carry. Thus the “emotions in the air” are indexed, archived and then, as if trying to communicate with the outside world, are rendered in the form of sounds different from the original ones. The sounds are generated through bone whistles, the first percussion instruments used by humans – a perfect example of connection where the organic matter intertwines with the mechanical one.

Already accustomed to the classical display of paintings, the spectator could easily pass by a color print which reminds of Jackson Pollock and the drip painting technique. Behind the print, however, an entire performance awaits. The image, if filtered through an app on a smartphone, turns into a virtual sculpture, expanding itself into augmented reality. The spectator can easily pass through the colored rivers on the canvas, being able to observe, at the same time, the artist’s moves during the process. Through this installation called Bodypainting V 05, Banz and Bowinkel explore the relationship between the virtual and the real world and how the separation of these two becomes less and less likely as technology advances.

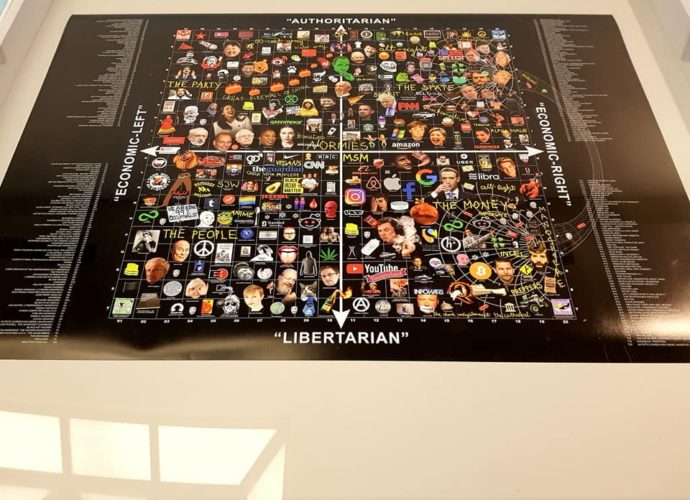

The artwork that talks about the inherent superficiality of social media is Beauty Lies In The Phone Of The Beholder by Maria Guță (a sort of postmodern clause to Paul Neagu’s manifesto). It represents an animated GIF, made out of 636 images, which reflects the myriad of virtual identities teeming the internet, initiating a dialogue about the way individuals identify themselves with the impossible beauty standards imposed by online “beauty filters”. In a similar note, a political compass placed in the central room frames an oversaturation of more or less familiar images that teem the internet as “memes”. It hints at politigram (Political Instagram), bringing into discussion the vast internet culture which coagulated itself especially through the agency of generation Z teenagers, gaining more and more radical political connotations. If ten years ago the internet could be considered apolitical, after the 2016 elections in the USA, political discussion blew up online. The political identities assumed by online users have become more and more niche, creating hundreds of sub-ideologies and a great diversity of opinions. The discussion about the online identities we take on or acquire is complex but seems to be treated superficially here, without materializing into something concrete. Unfortunately, this political compass seems to be thrown in the exhibition without any real reason, not having any connection to other artworks. Both works initiate multiple discussion leads, but unfortunately, they remain partially unexplored.

The Bucharest edition of The Wrong Biennale portrays the technological revolution in art (a revolution that took place long before). However, in a post-world, it looks like we have already been talking about post-internet and post-technology for some time now. While in Bucharest it seems that the artworld is only just settling in the digital space, which is still presented as a novelty, several hundred kilometers away art seems to want to escape from this paradigm. At the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, The Dead Web Exhibition presents the world after the collapse of the internet in a dystopian way. It all began in 2015 when an article on lemonade.fr predicted the collapse of the internet in 2023. Although this article is largely hypothetical, it made a lot of noise at that time, and so many artists were invited to imagine how the world would look like if the internet ceased to exist. Along with nonfunctional screens which project nonsense and books preserved in formalin, the exhibition suggests the abandonment in which contemporary people find themselves, as well as their nostalgia, portraying the importance of technology in people’s lives, but also their addiction to it. This curatorial discourse doesn’t question the relationship between humans and the internet, but rather moves the discussion even further, debating over contemporary man’s confrontation with a loss and the impossible attempt to reset everything. The Bucharest exhibition, even though is set to explore the current problems of the art scene, only ends up being a show where creative technology is on display and where spectators are invited to play with it and marvel. Every single artwork is complex in its own way, but put together, they seem like attuned musical instruments, the only common thread being the large umbrella of digital art that incorporates them. In recent years, the art-technology duo has become so commonplace that its mere display as a novelty is no longer appealing, not even in the Romanian context which seems to always drag behind. Thus, the question of the exhibition still remains: What is wrong with the artworld?

What is wrong with the artworld(s)? took place during 14-29.02.2020 at Rezidența BRD Scena 9, Bucharest.

Artists: Anna Adahl (SE), Giulia Bowinkel (DE), Friedmann Banz (DE), Dorin Cucicov (RO), Tristan Daniel Nicolas (RO/DE), Ciprian Făcăeru (RO), Maria Guță (RO/CH), Adrian Ganea (RO), Melodie Mousset (FR), Disnovation_org (FR), Maria Raskowka (FR), Alina Rizescu (RO), Saint Machine (RO), Răzvan Pascu (RO), Jakob Kudsk Steensen (DK), Mihai Zgondoiu (RO)

POSTED BY

Marina Paladi

Marina Paladi is from The Republic of Moldova and is a master's student in Heritage, Restoration and Curation Department at the Faculty of Arts and Design, West University of Timișoara. She is intere...

Comments are closed here.