Dear Nadira and Krishan,

We met your works for the first time at documenta fifteen, where you were present as part of the *foundationClass collective, and we instantly resonate with them. Especially the banner installation from Fridericianum, that recollected lots and lots of critical reflections on art and education, from both a pedagogical and communal perspective. It felt as a very intimate and down to earth approach to education processes, but also very powerful, as if they were a choir of different personal manifestos. Can you tell us more about the *fC, the way you carved your place in the Weißensee Kunsthochschule Berlin (KHB) and what are your struggles?

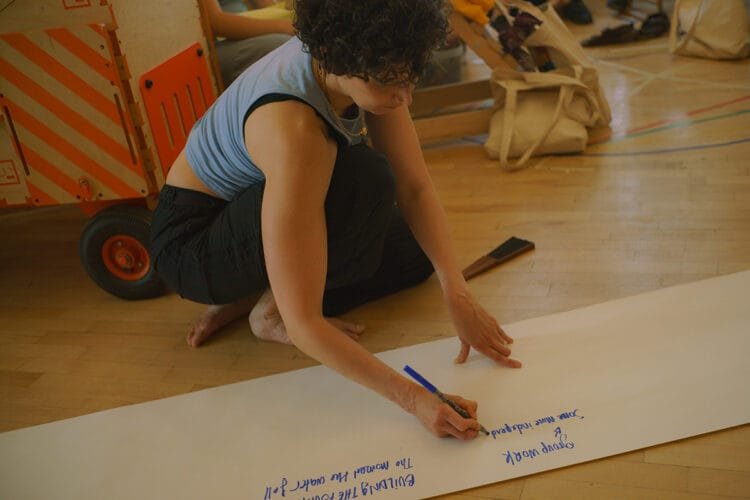

Nadira Husain: The project you’re referring to is called Becoming. It is an ongoing work that consists of compiling our thoughts, concerns, and reflections on arts education in the German context. The texts are printed on banners on one side, and on the other, there are photos taken mainly in our space at Weißensee Kunsthochschule in Berlin.

We could perhaps say a little more about *fC. This is an educational program that was created in 2016 to open access to art and design universities for people exiled in Germany, suffering from racism, or other forms of discrimination. Generally, we work with each group for two semesters. The program is free and provides the necessary materials. The educational team consists of people who, themselves or through their families, have experienced migration. The workshops and classes are built around a decolonial and transcultural approach, considering the participants’ perspectives and needs. They come with very diverse experiences: some are already artists wanting to study in Germany, while others are complete beginners.

We are part of Weißensee Kunsthochschule, which provides us with space and administrative support. We can also collaborate with the different workshops and departments, but all our funding comes from external sources.

As for our challenges: the main one is funding, which depends on Germany’s border and migration policies. The fact that we are not fully integrated into the university prevents us from establishing sustainability for the program. Another equally structural issue is the reason the program was created: to compensate for the lack of access to predominantly white institutions for people with immigrant backgrounds. As long as there are not more people from immigrant backgrounds or representing diversity among both teaching staff and students, the institution will remain non-inclusive and white-centered. We

Krishan Rajapakshe: When you ask how we’ve managed to carve out our space in the School of Art and Design Berlin-Weissensee, or what our struggles have been, the challenge really lies in finding our place within the art institute. Particularly in a heavily institutionalized government body, it’s a struggle to establish ourselves. Our very presence – whether it’s our appearance, our projects, or even our students’ backgrounds – can be seen as challenging the existing narratives, methods of teaching, and ways of thinking about art.

The fact that we, our curriculum, and our knowledge are sometimes perceived as threats only adds to the difficulty. For example, *foundationClass has existed since 2016, but we’ve never been fully integrated into the school. Despite all the work we’ve done over the years, the institute tends to celebrate us as part of their diversity program, like a decorative piece rather than recognizing our true value.

Not that we need their celebration, but a genuine acknowledgment could foster a meaningful dialogue between *foundationClass and the art school. Unfortunately, this has been lacking, and in some cases, there’s been resistance from their side. Some of our students, for instance, have faced rejection here, even though their applications were accepted by other art schools in Germany.

These challenges make it feel like we’re carving into a hard rock – like granite. You really need to know the right techniques, or else you’ll end up destroying your tools. That’s the strategy and concern we always have to keep in mind when dealing with the institute, particularly in the German context, though this may apply in other contexts as well. Art schools, whether progressive or conservative, still operate within the limits of the German national state project. They rarely push beyond these boundaries.

This isn’t just a challenge unique to Germany; art schools, in general, tend to play within this liberal-conservative framework, especially in Europe. Even the most progressive artists often operate within the confines of the nation-state, which is another challenge for us – especially those of us coming from different parts of the world. We not only have to form a curriculum but also challenge and integrate into this framework.

Despite these obstacles, the idea behind the *foundationClass is simple: we want to support and push people, particularly those with a migration background, to gain access to art school. But the question remains – how do we do that amid all these struggles, resistance, and closed doors?

One of our biggest current challenges is funding. After eight years, we’re reaching a crucial point where our funding is set to run out by April 2025. There’s a 90% chance that the *fC won’t continue physically after that, although we hope to carry on the idea of *foundationClass in collaboration with our friends and allies. However, without financial support, it’s hard to see how it will be possible.

We’ve been funded by programs like QIO, which was created in response to the significant wave of migration to Germany in 2015. But as the political mood in Germany has shifted, so has the availability of funds for so-called refugee projects. This change is directly impacting us, as it affects who can enter art school, who can study art, and ultimately who can cross German borders.

The loss of this funding has shaken the very foundation of our program. As a result, we’ve been in constant discussions with the Berlin Art and Design Academy, where we’re based. We’ve proposed that the school integrate us into their budget while allowing us to maintain our independence as a program. This would provide us with some much-needed security and stability, allowing us to plan for the future.

Without this support, the precariousness of our situation creates a toxic working environment, particularly for those who work with us and those we aim to support. Many of the people we support come from challenging backgrounds and need significant infrastructural and emotional support. When we’re struggling ourselves, it’s hard to provide that support effectively.

We’ve been trying to articulate this to the school for some time now – how integrating us into the school budget would give us the security to continue our work. The very act of existing within the school is a struggle, and carving out our space is an ongoing battle. But let’s see how this struggle continues. In general, I believe that maintaining independence within any institution, while still engaging with it, is always going to be a challenge.

You were already two times in Romania doing workshops and mentoring, and the students who met you on both the occasions were saying that you are the kind of educators that are missing here. As some of them stated, it was more valuable and inspiring to work with you than work within the high school and university altogether. When (and how) did you learn or (un)learn to be an art educator?

N.H.: When I was asked to teach at *fC, I initially hesitated because my previous experience at art college had not been enjoyable. However, *fC‘s political agenda aligned with what I felt was missing during my studies, so I decided to give it a try, hoping that being among like-minded people could bring about meaningful change.

My path to teaching art was shaped more by my involvement in various educational activities through associations and community work in France and Germany, rather than by my own practice as an artist. In Western Europe, art academy professors often lack formal training in teaching. During my studies, many professors were white male artists who embodied a stereotypical image of the heroic, autonomous artist. This model made me uncomfortable, as it often came with underlying sexism and racism, and a predominantly Eurocentric view of art. Coming from a Franco-Indian and Islamic multicultural background, I felt that a significant part of my artistic heritage was marginalized, making me ashamed because it did not fit the established norms.

Thankfully, we’ve seen progress towards greater gender parity among teaching staff and a growing inclusion of discourses on globalization and decoloniality. However, the old model of the autonomous artist professor still lingers in many art schools, upheld by long standing institutional structures.

In my teaching, I don’t focus on imparting my own art but rather on building upon what students bring to the table. I rarely teach alone; I prefer a team or duo teaching model, which exposes students to multiple perspectives. For example, Krishan and I often collaborate at *fC, and we also work with Minitremu like that. Additionally, Marina Naprushkina and I have co-taught an expanded painting class as guest professors at the UdK in Berlin over the past three years. Marina being also part of the *fC educators team.

Teaching is as much a learning experience as it is an instructional one. Alongside *fC and our work with Marina at the UdK, we participate in various workshops and additional training courses on topics such as gender, anti-discrimination, psychotic illnesses, first aid, and more. This ongoing learning helps us grow and adapt as educators with the social realities students face.

K.R.: The question about how or when we learned or unlearned to be art educators is quite intriguing. Personally, the experience in Romania has been significant. I’ve had many discussions with Nadira about it, and we’ve reflected deeply on how grateful we are for the experiences we’ve had. Living in a country like Germany, where there’s a struggle to be a good host and a general lack of hosting culture and humor, really made us appreciate our time in Romania. When we arrived, especially after the heavy workload and challenging experiences at documenta, the warm welcome we received in Romania, from both old friends and new acquaintances, was truly refreshing.

This warmth and hospitality made us more relaxed, something that I feel is missing in Germany. I want to express my gratitude for that. It’s important for us as artists to understand the significance of hosting – welcoming friends, family, neighbors, and even strangers, along with their knowledge, both oral and documented.

Coming back to your question about how we learned and unlearned art education – my background is different as I didn’t study art in a European context but rather in South Asia, specifically Sri Lanka. The art education there is very traditional, focusing mainly on skills. However, I believe my most significant art education happened outside of formal institutions, in the streets of Colombo, through endless late-night conversations with friends. We had a small hope and desire to make the world a slightly better place.

Creating art in Sri Lanka is very challenging due to the lack of institutional and state support, and virtually no funding. We had to think creatively about how to sustain ourselves and our art. Funding wasn’t the primary focus; it was more about how we could do what we loved while enjoying the process. Whether that meant finding alternative jobs or using our own money, we learned to be independent.

In Colombo, if you wanted to receive funding, you had to be close to embassies or cultural institutes, which wasn’t an option for many of us. So, I learned how to create art that was relevant to my size, to politics, and to the realities of life, always with the hope of contributing to a better world. For me, it’s about empathy, something I find lacking in the German art education context.

Nadira and I share a lot – our art, our lives, our values, and our politics. This common ground allows us to work together and appreciate each other’s art without striving to create heroic or toxic environments. Instead, we focus on being relevant to society and finding joy in the process. Art, for us, is a medium to navigate our social, cultural, and political relationships.

In teaching, my approach is to create a space first and foremost – one without ego, where we can get to know each other. Understanding each other’s struggles is key. Whether in my classes or workshops, I place a lot of importance on the initial stage of creating a respectful and meaningful space for dialogue. It’s about making friends first, then discussing art.

This space must allow for emotional expression – whether laughing, crying, or making jokes. It’s in these spaces that we can begin to develop and articulate our knowledge of life through art. When discussing art education in schools or workshops, I always emphasize that art is not just about creating objects; it’s about how much the piece matters to you, to your friends, and to society.

Facilitating a workshop or class isn’t about forcing everyone to work. If someone needs to rest or just isn’t feeling up to it, that’s okay. The most important thing is whether we’ve created a comfortable and communicative space. If we establish a learning environment that is open, empathetic, and understanding, we allow true learning and unlearning to happen.

What I observed in Romania and in Timișoara, through conversations with art camp participants, is that it’s not just about talent or knowledge. It’s about setting up a space where it’s okay to make mistakes or to rest when needed.

Creating a space with empathy, joy, humor, critical thinking, and politics – especially radical politics – is crucial. We’re not liberals, but we do strive to offer different perspectives. This approach enables learning and unlearning. I’m glad our friends and participants enjoyed the workshops because maybe that’s what made the difference.

I don’t want to undermine the efforts of art school teachers because often the atmosphere of the institution, not the person, plays a role. However, individuals do have the opportunity to create learning spaces if they choose to. This is something I’ve seen in initiatives like Minitremu, where spaces are created not just for learning, but for hanging out, joy, and humor.

Artists aren’t just confined to studios, creating genius works in isolation. What I did in Sri Lanka involved meeting many people and forming genuine relationships with them – whether they were neighbors, friends, or even strangers. This genuine desire to connect is what drives my teaching. I want to learn about the people in front of me, understand their desires, and share in them.

This approach makes us vulnerable to unlearning, which is essential. Acknowledging when we’re wrong or when we have more to learn requires flexibility. Perhaps that’s what we’re trying to offer, and I’m glad our friends and participants have felt that as well.

One time at Minitremu you presented, among other things, the ”Toolkit für Machtkritische Projektverwaltung”, which we could translate as a Project Management Toolkit for Power-Critique? Anyhow, you’ve come with this concept of transparency, or being transparent in front of these mostly opaque institutions, that eventually decides if the existence of a cultural or educational alternative is justified or not. We felt it very deeply as most of our projects are public funded and we were always stuck in this dilemma, how transparent we should be. Can we talk a bit more about this?

N.H.: The ”Toolkit für Machtkritische Projektverwaltung” (Toolkit for Power-Critical Project Management) was created primarily to share our experience with other initiatives like ours, which are partially part of the institution but also critique it. Solidarity and the exchange of experiences among such initiatives are vital for our survival. There is, of course, a significant ambivalence in hacking the institution while openly explaining our methods. For example, when discussing strategies like taking the money and running, or the power of the institutional stamp that grants us a portion of institutional authority. In working with structurally marginalized individuals, these stamps can sometimes work small bureaucratic miracles crucial to their lives.

Our goal is to open institutional access to marginalized individuals who currently lack it. To achieve this, we must engage with and improve the system from within. We are fortunate to still operate within a democratic framework where institutions are subject to laws and democratic principles. However, institutions can be opaque and may make decisions that undermine the democratic and social justice principles we advocate, often by complicating processes or using the system’s complexity as an excuse to impede progress.

*fC is a political tool, and the toolkit is an extension of this approach. While institutions are large, slow-moving systems, the ‘pirate entities’ that emerge from them also have the power to challenge and transform them. As this toolkit outlines, it is crucial to find the right balance between strategic diplomacy and a healthy dose of discretion.

K.R.: The question about transparency was mostly addressed by Nadira, but I’d like to extend some areas of that discussion. As Nadira mentioned, the *foundationClass is a political tool, and these toolkits are an extension of this approach. You also mentioned transparency, which I see as a strategy to hold institutions accountable. When we look at documents or toolkits about running projects, they often show how to behave well within an institution and outline various strategies. But, if you think deeper, these toolkits also subtly expose the ugly things happening within institutions without explicitly mentioning them.

So, our approach to transparency is really about holding institutions and the people within them accountable and revealing what goes on behind the scenes. When we practice transparency, it forces other parties to reciprocate with a similar level of openness. As Nadira mentioned, it all works together – finding the right balance of diplomacy, radical politics, and social networks helps create the *foundationClass as a tool. This knowledge becomes a proxy, a way to crack the institution open.

Transparency, in this context, has the power to expose and reveal the flaws within a rotten institution, showing why certain things don’t work. That’s why we’re doing things differently, and we’re transparent about our methods. But that very transparency pushes the institution to reveal itself as well.

So, in that case, the toolkit you mentioned and the general approach we offer in the foundation class include all these steps. While we offer these tools to our students, we also implicitly tell them how the institution functions. This gives them the opportunity and the choice to decide whether or not they want to engage with it. For me, transparency is about holding the institution accountable

Since documenta and the pedagogical questions you raised, a specific one has grown with us, and it seems more and more complicated to answer: ”Who has access to art schools?”. We understand that you relate this question with Germany and the privilege of being in the art world, which is somehow restricted for the people who are refugees or immigrants. At the same time, from a local perspective, it is curious how your question needs to define first what is art, what is a school and so on. In theory, anyone can access an art school, free of charge, yet fewer students are willing to do so, as arts are the last path one should pursue as a career. And if one is allowed or encouraged to, schools are stuck somewhere in the past or they made a huge step straight into the entrepreneurship of the creative class, art being synonymous with the lifestyle industry today. What are your thoughts about it?

N.H.: It’s easy to assume that in Germany, access to art and design studies – aside from the common entrance exams – is relatively open to all. This is the image the system often projects. However, those who participate in and succeed in these competitive exams typically come from the white middle class, and the teaching staff mirrors this lack of diversity. This reveals the exclusivity embedded within the system.

While higher education in Europe is generally financially accessible or made possible through scholarships, this is not enough. To enter an art school, one must feel a sense of legitimacy and be able to envision themselves thriving in this environment. Yet, these artistic and educational institutions are fundamentally White and structurally racist. Without significant changes in the perspectives of the teaching staff, curricula, and access policies, the status quo will remain unchanged. Institutions must genuinely desire to open their doors, but often, we see that the rhetoric of openness, diversity, and anti-discrimination is preferred as long as it remains just that – rhetoric. When these principles are actually put into practice, those in power, who are predominantly white, fear losing their privileges.

We are currently in an era of tokenism, where those who suffer from discrimination are paraded as exceptions to the rule, used as minority tokens. While these individuals might manage to enter the system, surviving within it is an entirely different challenge.

From my experience as an educator, it’s evident that institutions often welcome individuals from immigrant backgrounds who bring critical, intersectional, and decolonial perspectives. However, these individuals are often relegated to temporary or guest lecturer positions, rarely receiving permanent contracts. Krishan and I are all too familiar with this scenario. We feel we are sometimes brought in to perform the work of structural diversity for white institutions, yet these institutions do not offer us sustainability. Some activists with radical views reject this exploitation and refuse to collaborate, while others accept it, seeing it as a means to achieve small but meaningful progress.

Since *fC’s mission is to support individuals with challenging experiences related to immigration, racism, and discrimination in gaining access to university. Given this, one might question why we would encourage them to enter a system that can be hostile and won’t garantie a professional future. While the art world often has an elitist nature, it still exists within the cultural domain, where diverse voices can be heard and can have influence. Many people, despite their difficult life experiences, have a deep need for creative expression. Perhaps it’s naive, but I believe that this desire should be accessible to everyone. At *fC, we don’t want to sell dreams; instead, we strive to prepare participants for the harsh realities of the field while recognizing and nurturing their creative and artistic potential

K.R.: I think the question about who has access to art school seems straightforward. As you mentioned, theoretically, it could be everyone. But I believe the question goes deeper; it’s a matter of class.

It’s also about who has access to certain knowledge in the first place, considering their family background and social class. Studying art is a privilege, but for some students, it’s a last resort. In general, I believe that the concepts of art and school belong to an old, predominantly white European world. We are living in a time when artists need to merge art and life, with life itself becoming a school, both socially and politically.

However, there still exists a structural separation between school and art. Personally, I don’t believe art schools are the most progressive places. Whether in Germany or elsewhere, these schools often produce a specific type of aesthetic and ideology, ultimately preparing people for the art market. Only a few artists today engage with social and economic change, as these topics are often ignored by art schools.

The terms “contemporary art” and “fine art academies” are used to alienate people, encouraging only a few hyper-intellectual or hyper-intelligent individuals to succeed. To me, the more important question isn’t just about who has access to art school, but what students do with art once they are there. Do they make friends or engage in politics, or do they just become artists? And if so, what does that mean?

Access to art school is closely related to class. In Germany, art schools may claim to be free, but without the knowledge of the language or how to write applications, get funding, or obtain scholarships, how will one fund their studies? Even with student loans, how will they be repaid? After three or four years in art school, what comes next? I know many people who studied art and now face the harsh realities of life.

The real question is: what are we going to do with the knowledge we gain from art school? Perhaps by exploring this, we can find common ground and ways to apply art school experiences to the political world. Today, the art world frequently uses the term “community,” but what are artists or the art world actually contributing to the community? Is it progressive, or not? There are many questions around this.

When considering the slogan you chose from documenta, particularly from the *foundationClass, it’s clear that, from an identity politics perspective, it questions who has access to art school and touches on other political layers. But in the end, the *foundationClass also creates individual artists; that’s what we do. We prepare people with individual portfolios. The best we can do is to raise awareness about social and economic realities and communal needs.

But overall, I don’t believe that even if someone gains access to art school, it will change much in the world or politics unless that person has social and class consciousness.

Our last question is related to your presence in the Minitremu art camp, where you coordinated different workshop sessions of drawing and painting, but also dialogue sessions, self expression exercises and so on. It was very empowering for the participants but also for us. It allows us to hope and dream again. How do you think we can make this sustainable for the future?

N.H.: Being with you in Timișoara on two occasions was a very special experience for us. One thing you excel at is creating platforms with time, which allows many things to happen. This open time gives everyone the opportunity to find their place and contribute at their own pace, fostering genuine exchange. It provides a gentle way to delve into deeper topics, starting by getting to know each other. We can engage in exercises to physically connect with ourselves and the shared learning space – not just intellectually. We can also hold sessions where everyone shares their current state in the process. These moments of self-reflection are crucial in any kind of learning, as they allow us to take stock and gain clarity.

The summer camp we recently participated in with you was a fantastic experience. We shared and created a collective space for exchange and mutual learning. Between shared meals, late-night conversations, parties, and various activities, I never felt burdened with the responsibility of leading the group as an artist instructor. Whenever I initiated something, everyone participated actively, and we co-created the workshops. This level of collaboration is not always the norm; even though we try to avoid replicating the authority and rigid structures sometimes present in art education at *fC, we occasionally have to navigate deadlines and evaluations-feedbacks. These can introduce stress and create dissonance. When faced with such situations, I try to take a step back and remind myself that deadlines and other constraints are not the ultimate goal. This helps me approach the situation with a different mindset, reducing pressure and avoiding negatively impacting the students.

How to make this sustainable for the future is a vast question. Perhaps we should pay more attention to introspecting our teaching methods, accepting that we make mistakes and learning from them, rejecting certain conventions imposed by educational institutions, and organizing ourselves into solidarity and political groups when we share similar visions. It is also important to always keep the contexts and realities of the learners at the forefront, and recognize our boundaries as educators. These are just a few ideas that come to mind.

K.R.: I also mentioned earlier, as Nadira did, that we had an amazing time. I’m really thankful and appreciative because it gave me so much energy personally. Nadira and I talked about it, and we both felt a different energy when we left Germany and came back home to Berlin. It was a unique experience, especially staying in one place.

This entire art camp really opened my eyes. It created a space for dreaming – a space for the right kind of dreams. It wasn’t just another institutional project during the art camp. What we experienced and shared went beyond formal education or institutional approaches. Late-night talks, staying in one place, creating a little community over those 10 days, and building trust – it was all so meaningful.

I remember when someone was absent, and we all noticed, asking, “Where is so-and-so?” Then someone would bring food to them. These small gestures may seem insignificant, but they stayed with me because that’s what a trusting, friendly environment looks like. It’s about creating a space of trust, and you were great facilitators of that.

The participants were open, and all the elements of the art camp – the people, the space, even the cats and plants on the balcony – came together to create a beautiful, trusting environment. It wasn’t just about the humans; it was about the entire space, including perhaps even the ghosts in the city. All of this combined to make the art camp a place where we could dream together.

Sustaining the future is a big question. Can artists sustain the future? I sometimes doubt it because we are part of the problem. But by recognizing that, we can try to navigate in a way that doesn’t make things worse.

I felt hope when leaving Timișoara – a hope in people, in the desire to create spaces, to gather, meet friends, and hold onto the nostalgia of those days. That’s what sustains the art camp and a sustainable future. Wherever I go now, I’ll take this experience with me as an example, and I’m sure all the participants will do the same in their future artistic endeavors.

Setting up a space taught me a lot about being a good guest and host. The most important thing I learned was how to sustain artistically in the future – how to create a more sustainable future by finding the right recipes for dreaming together.

I remember visiting Cosmos, a small venue in Timișoara, where people were dreaming of building something out of nothing. The most important thing isn’t funding, money, or fancy tools. It’s about desire, collective dreaming, and sharing our lives with each other. During those 10 days, we dreamed together about what our art school and artistic productions could be like. It was truly magical.

To sustain the future, we also need to think about the curriculum – what we’ll offer to art students and how we’ll offer it. Traditional art schools often lack an empathetic approach to art, and they might not sustain themselves. We could end up creating more egos in society. What we tried to do in the *foundationClass, and what I saw Nadira doing in her teaching, was to create an environment where we could grow together.

It’s about getting people to think about others and their struggles, fostering solidarity, and translating those experiences into art. It’s not about extracting knowledge and producing art in isolation, but about creating dialogue and conversations. Minitremu was a great example of this. It sparked many conversations.

If any institution were to observe what we were doing, they might question, “Is this art?” And that leads to bigger questions like, “Who has access to art school?” and “What is art?” These aren’t simple questions with straightforward answers. Art is about processes – emotions, artistic production, and how we intersect our political, economic, and social lives to create a language for discussion and dreaming.

We need to create spaces to experience, feel, and execute these ideas. As artists, it’s not just about talking; it’s about doing. I learned so much from other facilitators like Andrei, Nicoleta, and EL Warcha. We all facilitated the space while learning from each other, and that’s where sustainability comes in.

We didn’t approach this as a *foundationClass thinking we knew everything. Of course, we knew what we were doing, but it wasn’t about being the only ones with the answers or the “geniuses” of the process. To sum it up, sustainability comes from empathy and generosity in our work as artists. That’s what will sustain the world and its people.

I must be honest – I’m not sure it will sustain us economically because of the heavily capitalistic market we’re in. But by continuing our work, we might influence even the capitalist market to pay attention to us. That’s how I believe sustainability can happen.

POSTED BY

Minitremu

Minitremu is situated somewhere between art and pedagogy, being a laboratory for aesthetic experiences and creative development, through which children and young people can get in touch with artistic ...

Comments are closed here.