The 14th edition of BIEFF, titled Serious Games, explored the structures that run our world – from war to the office – through an ironic but politically engaged lens. It echoed the critical spirit we have grown accustomed to from the festival, touching on those issues common to today’s heated debates. Technology, memory, ecological and cultural destruction, and perpetual uncertainty fill the collective psyche to the brim, leading to emotional disunity that teeters between despair and bitterness. In this year’s selection, we particularly lingered over films that weave a secondary theme: life through the prism of work. Central to this discursive proposal was the international short film Works and Days. The rest of the films deal with the theme of work rather tangentially, but I also found strong thematic echoes in the Portuguese feature Fire of Wind.

Works and Days – An Infinite Thing

The third international short film series presented a selection of films with an anti-system ethos. The screening began with Very Gentle Work (dir. Nate Lavey), which uses fictional framing as a pretext for a documentary approach. The voice-over movie begins with the narrator introducing us to an old friend of his who was exceptionally interested in the history of violent anti-capitalist anti-capitalist demonstrations. As the route is traced on a walk during his lunch break, we are led through the streets of New York and initiated into a world of marginalized stories. The milestones are sites of various bombings and violent leftist protests. The simplicity of the imagery creates an eerie air: most of the sequences show the city empty, full of people’s footprints but devoid of their presence, steam clouds filling the screen. A bomb went off here; someone died here. The geography of a revolution is swallowed up by skyscrapers that grow carelessly over the traces of the past.

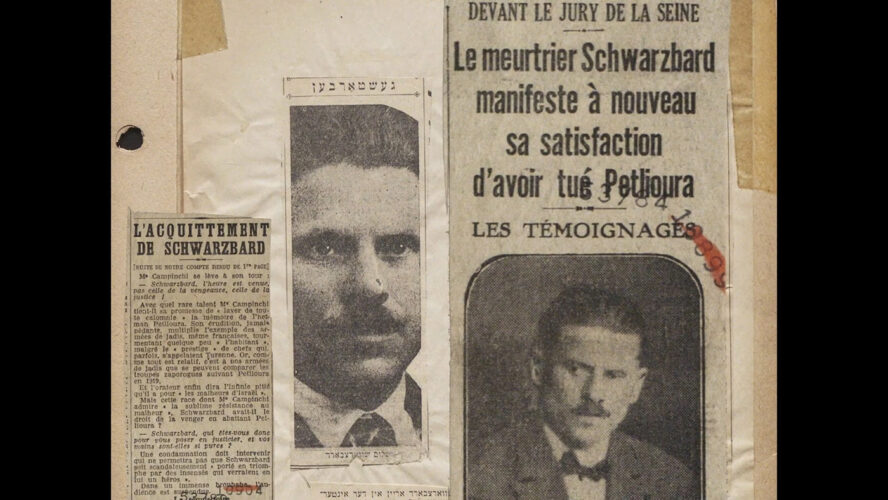

Using archive footage, the filmmaker uncovers the story of Sholem Schwarzbard, an anarchist activist acquitted of murdering a commander who had taken part in pogroms. Lavey puts forward the idea that a world in which atrocities are committed cannot be met with simple non-violence, while at the same time paying homage to revolutionary work. Schwarzbard’s spirit, as well as his friend’s admiration for him, are the moral landmark of the movie. The need for revenge is not criticized, but justified and sanctified (“The century in which I was born yearned for revenge, I am only trying to preserve the memory of that yearning.”). The friend’s story in the movie doesn’t have a clear ending, but we are hinted that he followed in the footsteps of his heroes. How we relate to his disruptive actions is for us to decide.

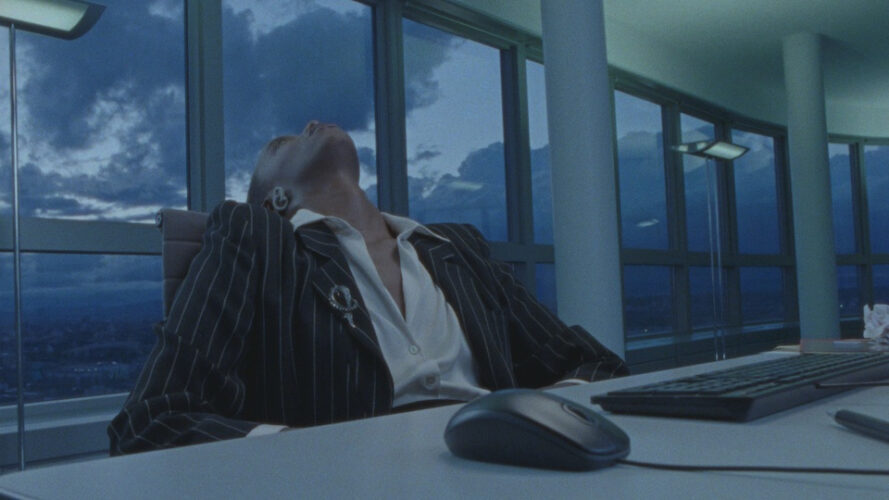

To Exist Under Permanent Suspicion (dir. Valentin Noujaïm) translates the often-absurdist life of our century into a surreal and sardonic movie. The short follows a businesswoman as she works on a project for a new office block. The first part of the movie is grounded in reality through everyday sequences – a cigarette break, a presentation at work, a late night at work. The blue lighting, uncomfortable dialog and plunging shots render this monotony in an almost grotesque way. The protagonist is the caricature of an alienated person par excellence, her experience not an inch beyond her role as an employee. The surfacing of this seemingly endless blackness occurs when she actually consumes her work, architectural plans emerging from the computer and consuming her like a digital zombie.

After that, animal liberation: colleagues become prey, furniture a natural obstacle like a fallen tree in the jungle. The dynamited block becomes a firework. For a moment, we can enjoy the glee of the annihilation of a meaningless existence. The ease with which the destruction comes reveals the shaky ground on which the post-industrialized world is built, numbered in corporations and offices. More than just a playhouse of playing cards, the genesis of this order contains the seeds of its own destruction. This sense of precariousness is also what animates Gala Hernández López’s short film, for here am I sitting in a tin can far above the world. The filmmaker has an imaginary, one-sided conversation with Hal Finney, an American programmer closely linked to the invention of Bitcoin. In our world, Finney is cryogenically preserved. In the imagined world, millions of other people have followed in his footsteps to escape a post-cryptocurrency global collapse. The schisms of modernity are made visible through the simultaneous presentation of two screens, simulating the informational cacophony to which we are exposed daily. López only highlights the bizarre system we have constructed for ourselves, one completely detached from the natural. The finality of such an anti-organic philosophy is a complete rupture from the body, in this case by cryogenics. Instead of making the present a better place, we put all our hope in a seemingly more advanced, more sophisticated tomorrow. The fear of the future under the sign of economic insecurity is the defining feature of the current age, and these two short films capture the human spirit in the process of an agonizing adaptation.

We conclude with The Seventh Shift (dir. Nataliya Ilchuk) and Workers’ Wings (dir. Ilir Hasanaj), which share a similar, meditative sensibility. Besides, the common over-emphasis on the life of workers in the former Soviet bloc makes the two shorts sketch a microcosm of wage-earning life more familiar to our culture than the glass towers of Very Gentle Work and To Exist Under Permanent Suspicion.

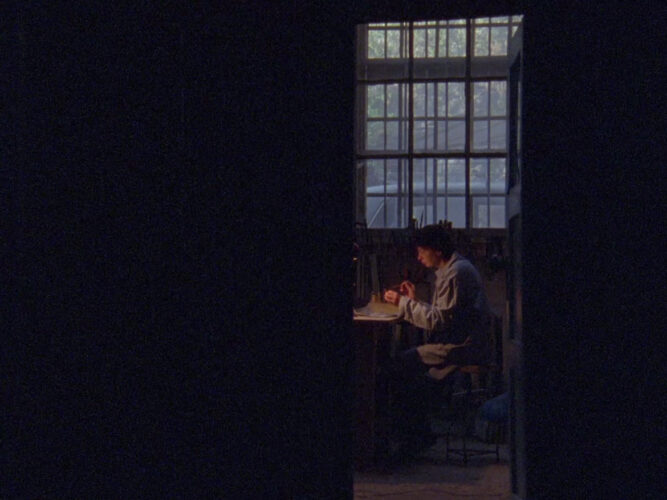

The Seventh Shift follows an unnamed woman over the course of any given day, moving from job to job, sunrise to sunset. The dialog is eschewed, letting the movements of routine create a rhythm. Our protagonist is alone. We don’t know her relationships with other people or why she is forced to fill her days with endless work. We can only assume what’s most realistic: the pay isn’t enough and human relationships are secondary to subsistence. The subject matter is abject (living limited by a minuscule horizon), but the filmmaker’s treatment doesn’t reduce the experience to anonymous monotony. The small-town industrial landscape, painted in tonal hues, feels like home, a recognizable universe for all its flaws.

If the previous short film is a textbook realism, Worker’ Wings uses certain expressive touches for a homage-like representation of its subjects. The movie documents workplace accidents and disabling injuries to employees. In the face of machinery made of tons of metal, the limp body is sliced with ease. We return to the themes of precariousness and uncertain futures: the men portrayed are put in a situation where their essential workforce resource – their body – has been depleted. The scars and wounds are permanent and the pay is too low to live on. An absolute sacrifice is met with indifference, what remains is the forced martyr. The workers’ bodies are bathed in a thick, saturated light. Deep reds and blues flood the image, creating a chromatic disruption in a “gray” existence. The director’s eye restores dignity to a space in which everyone’s individuality counts for little.

Intergenerational Communion: Fire of Wind (dir. Marta Mateus)

Mateus’ movie is as gentle as it is firm. After a bull rampages through a grape orchard in Portugal, workers flee into the forest for cover, climbing a massive tree. Despite the danger lurking around them, taking refuge in the shade of the branches seems preferable to mechanical, repetitive and mute work in the heat of the vineyard. The spirit of the movie is quickly captured: when the owner tries to climb up as well, his mistreated employees refuse to help, abandoning him to the fate of the feral bull. At the same time, no one takes revenge on the young worker, whose bleeding wounds had lured the animal in the first place. Illustrated through slow, pictorial frames, we see how people begin to tell stories, to recall their lives, and to share bread and wine in this liminal space. The protection of the old tree, reminiscent of a benevolent god, gives the story a biblical parable-like accent. As personal histories float in the air, time flattens, the heroes of the past flow into the present. The identity of each narrator is not as important as his or her role in the monographic tapestry of this rural community.

The director, who hails from the region captured in the movie, worked with various locals throughout the production, from script to shooting. The characters are not played by actors but by people she grew up around. The creative decisions taken are the opposite of an authorial vision, where a single personality dominates everything we see on screen. The result of active collaboration is a movie that feels like part of the landscape, really the product and reflection of a collective bound by a shared space and past. The feeling after exiting the movie theater was, despite all the bad, a refreshed hope for a better world.

The world of work is no small thing, but a serious game from which none of us can escape. It is a common denominator of humanity, it consumes more and more of our existence yet remains underdeveloped as an object of artistic creation. In times of major change, there is a resurgence of a renewed preoccupation with work, which becomes unworthy as a condition of survival. We live in a periodically seething tension, which pushes us to believe that something is bound to change soon, as soon as possible. In this context, the films at BIEFF are both vent and protest, dismantling and ideation, a question and an answer.

Translated by Liliana Popescu

POSTED BY

Alexandra Roceanu

Alex Roceanu is a visual artist and writer. She currently studies Graphic Design at the National University of Arts in Bucharest and writes for the feminist film club F-Sides. She is passionate about ...

Comments are closed here.