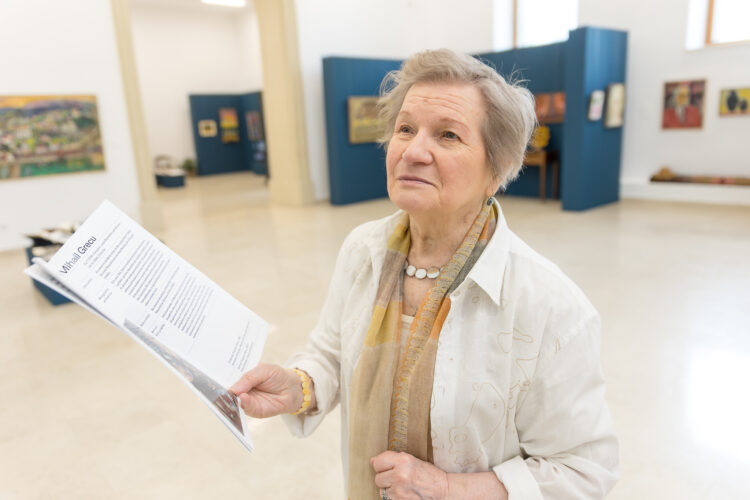

Ludmila Toma (b. 1939, Fedotovo, Moscow) graduated in art history and art theory (1963) and received her Ph.D. in art theory from the I.E. Repin Institute in St. Petersburg (1979). During her professional career she worked as a guide (1956-1958) and scientific researcher (1963-1971) at the Republican Museum of Fine Arts in Chișinău, scientific researcher at the Academy of Sciences of Moldova (1974-1983), Professor at the Republican School of Fine Arts in Chisinau (1983-1996), Senior Research Scientist at the Institute for the Study of the Arts of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova (1991-2017) and Associate Professor at the Academy of Music, Theater and Fine Arts, Chișinău (2005-2023).

During the Soviet period she consistently supported innovative trends in art and advocated for the creative freedom of artists and critics.

Ludmila Toma is the author of numerous monographs, including Mihail Grecu (1971 and 1997), Claudia Cobizeva (1979), Portret v moldavskoi jivopisi 1940-1970-е godî (Portraiture in Moldovan painting, 1940-1970; 1983), Ada Zevin (1983), Moisei Gamburd (1998), Eugenia Gamburd (2007), Dimitrie Sevastianov (2012), The Artistic Process in the Republic of Moldova (1940-2000). Painting. Sculpture.Graphics (2018). She has authored approximately 200 scientific and popularizing articles in various publications.

Dear Mrs. Toma, tell us how you, an experienced curator from Chișinău, came to curate the Bucharest exhibition “The Colors of the Thaw. The Bessarabian village in the painting of the 1960s”, which opened on the 18th of april at the National Museum of the Romanian Peasant.

This event came after I met Victoria Nagy Vajda în Chișinău, when she was preparing a very serious work – the two-volume catalog of Valentina Rusu Ciobanu’s works. We realized then that we had common interests: a thorough knowledge of cultural history, in particular the history of fine arts, and the desire to popularize authentic aesthetic values that have undeservedly remained in the shadows.

How did you envision the exhibition and what is special about it for the public in Bucharest, but also for the public in Chișinău, which only has access to the online materials of the project?

Victoria Nagy Vajda, the author of the project, wanted to highlight an extremely important period in the history of Bessarabian painting, so she gathered little-known works similar in subject matter, from various collections. I believe that the novelty of the presented materials can amaze not only critics and art lovers from the Romanian capital, but also all the visitors to the wonderful Museum of the Romanian Peasant, coming from Chișinău or other cities and passing through this exhibition.

As the curator, I was impressed by the layout of the space, which serves the purpose of the exhibition very well – to showcase the chromatic richness of the works and the symphony of color harmony, highlighted by the white and blue of the walls and background panels. The idea belongs to Mrs. Nagy Vajda, but some of the challenges that arose in the placement of the paintings were discussed by both of us. As a result, the visitors can perceive the beauty of the art of the fourteen painters presented – among them well-known masters of the “senior” generation: Mihail Grecu, Valentina Rusu Ciobanu, Glebus Sainciuc, Ada Zevin, Igor Vieru – in all its variety, but also in the similarity of themes and means used.

In addition to its aesthetic goal, the exhibition also has an educational purpose, which it fulfills in several ways. In addition to the canvases, the exhibition includes folk art objects that inspired the painters: cups and pitchers, a traditional carpet, etc. Visitors can familiarize themselves with the creative journey of each artist by reading the biographical notes in the exhibition catalogue. To better understand their work, each canvas is labeled with short explanatory texts, and the pages reproducing the painters’ best-known works are labeled with monographic albums of earlier works. Visitors who want to find out more about the artistic atmosphere of the 1960s can watch a documentary film in which several critics and art historians describe it. All these means of expanding the instructive scope of the exhibition were designed by Victoria Nagy Vajda.

Why were works from the 1960s chosen for the exhibition?

Because that period marked a major change in the history of art in the Republic of Moldova. As a result of Khrushchev’s “thaw”, the creators’ outlook on life became more optimistic and the need for a renewal of the creative spirit emerged.

After Stalin’s death there was a “thaw” in various fields of activity. Was it delayed in the case of the visual arts?

The developments of social life and the creative field are not synchronous. The evolution of art has its own laws, linked to the specificities of aesthetic language. Although living conditions undoubtedly influence the fate of creators, which sometimes leads to tragedy. The totalitarian regime, with its harsh ideological and political requirements as well as its vulgar criteria of appreciation, slowed down the natural development of the art of already trained masters and hindered the creative development of young painters. The first decade after the Second World War was particularly difficult – years of destruction, drought and famine. In order to support their families, artists were forced to sign contracts with the Ministry of Culture and create paintings with specific themes for jubilee exhibitions. They were required to depict the signs of the new in detail, in superficially lifelike forms – that’s what the infamous “method of socialist realism” was all about. Any artistic convention was viewed with suspicion by the regime’s ideologues as evidence of “formalism”, a “burden of the past” that creators had to rid themselves of. Despite these demands, painters who had learned their craft before 1940 continued to draw inspiration from the traditions of European art – complicating their livelihood but saving them from artistic decline. Their interest in the authentic beauty of man and nature usually shielded the artists from ostentatious festivism and led them to create paintings that reflected sincere feelings.

As a participant in the artistic scene of the Republic of Moldova ever since your youth, you have spoken several times about important events of the past, for example about the lasting impression left by the exhibition of Romanian paintings of the 20th century, organized in Chișinău in 1957. Do the masters of the older generation have memories of the changes that took place during the “thaw”?

Such memories rarely appeared in the press. In an interview that art critic Olga Garusova conducted with Ada Zevin, the painter says: “It was a well-prepared explosion. (…) The situation in the 1960s, with a very active artistic life, was unique. Fate then brought several artists together and allowed them to enter into a communion of ideas. At the end of the 1930s, I befriended Mihail and Fira Grecu in Bucharest, and later, în Chișinău, I was friends with Dimitri Sevastianov, Valentina Rusu Ciobanu, Glebus Sainciuc. We were united by our passion for art, similar interests, and our everyday affairs. (…) We were rooted in French post-impressionism, Romanian painting, Russian culture, Moldovan folk art, which we discovered in the early 1960s and which played a huge role in the formation of our generation. (…) We were attacked and considered ideological enemies: it was considered that the people didn’t need our “chamber” art. But we were simply trying to honestly defend what we considered to be authentic art. Later, our creations became a reality that had to be taken into account”.

Why did you choose this particular exhibition format?

These days thematic exhibitions are rarely organized in Chișinău, let alone exhibitions of Bessarabian painting in Bucharest. During the Soviet era they were frequent, but they had a propagandistic function. The commission of the Ministry of Culture signed contracts with the painters in advance and controlled the execution of the commissioned pieces. In the painters’ studios, however, there were works created at the painters’ own discretion, mostly studies. Many of them are connected with the life of the Bessarabian villages.

Rural motifs were important for painters of different generations. Artists have always admired the beauty of nature, have been impressed by the peasants’ inner qualities and the marvelous fruits of their creative spirit, have been attracted by the aesthetic aura of the people’s way of life, an aura that has influenced the sense of harmony in many of them – those born in the village – since early childhood.

The exhibition also includes works by artists who were young at the time. How did they continue their artistic pursuits under such harsh criticism?

The emergence of new trends in the work of mature painters impressed and broadened the horizons of young artists – Eleonora Romanescu, Georgy Jancov, Olga Orlova, Elena Bontea, Sergiu Cuciuc – and even of students of the Republican School of Fine Arts, whom the teachers brought to the same villages where the innovative painters were creating their sketches and discussing various means of pictorial expression. As a result, the graduation paintings of such talented colorists as Ludmila Tonceva, Sergiu Galben and others, related to Moldovan village life, represented the art of the Moldovan SSR not only in local but also international exhibitions. And the fact that the current exhibition includes works by artists of different generations is proof of the vitality of the school of painting that was formed at that time, of the continuity of tradition.

What are your plans for the future? Are you planning to return to Bucharest with a new exhibition?

I’m planning two album monographs about painters whose creative path I think is worth studying. Besides that, I am ready to continue collaborating on important projects. I will be happy to put my knowledge to work on a new project, if asked, and possibly return to Bucharest even during this year.

Translated by Dragos Dogioiu

POSTED BY

Ana Daniela Sultana

Ana Daniela Sultana (b. 1984, Bucharest, Romania) is a curator, artistic advisor and columnist. With a bachelor's in philology and communication sciences, she completed a master's degree in curatorial...

Comments are closed here.