Xiaoyu Weng is a curator and writer based in New York. Her curatorial and writing practices focus on the impact of globalization, identity, decolonization, and the intersection of art, science, and technology. Most recently, she was the Carol and Morton Rapp Curator and Head of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto, Canada. Previously, she was The Robert H.N. Ho Family Associate Curator at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York, where she curated highly acclaimed exhibitions such as “Tales of Our Time” and “One Hand Clapping.”

This interview with Xiaoyu Weng was prepared in the context of the Fall 2023 Curatorial School edition, which will take place in Cluj Napoca and Timișoara between November 13-17, the deadline for applications is October 6. Xiaoyu Weng will participate as a course leader, along with an international team of curators and artists. Xiaoyu Weng’s curatorial and research work addresses themes related to identity, but also topics related to the impact of technology on the body and everyday life, as well as the impact of current global politics. Ironically, the interview was sabotaged precisely because of the elusive nature of the recording device.

So here is a short version of the transcript as recorded in human memory and notes taken on the spot, with the belief that somewhere, stored in some external bits (bits never go away, do they?) of their own digital nature , the full 60+ minute dialogue still exists.

Horațiu Lipot: Hi Xiaoyu, let me first ask you if you have ever worked, or have a general context, even briefly regarding the Romanian art scene? I know that you had different collaborations with Cosmin Costinaș. I also know that the Kadist Collection where you were Founding director for Asia Program hold some works by Ciprian Mureșan and Alexandra Pirici.

I was particularly interested in this because the past year leader of The Autumn School of Curating, the artistic director of SMAK Philippe van Cauteren, pointed out about his direction of Kathmandu Triennale, that sometimes is better to have the outsider look, because you could see things differently and see through what everyone else perceives as evidence. What do you think on this aspect?

Xiaoyu Weng: I haven’t had many opportunities to work with Romanian artists or curators, apart from Cosmin Costinaș, whom I have known for more than 10 years.

I agree with a fresh perspective which takes you to a new place and makes you to listen, to make contact with a new perspective. However, there is still the risk of a kind of cultural “neo-colonialism” tinted with the colonial legacy that we all should be cautious about: (This is, of course, not a comment on Philippe’s work as I believe he is well aware of the situation and so is Cosmin in the context of Kathmandu Triennale and working in Asia in general).

The approach of some European or American curators, who maintain a very privileged power position when coming to a so-called “culturally less privileged” place to organize programs with a unilateral perspective to define what art is, often based on a Western tradition and standard. So some art becomes “better” and some becomes “worse” or “not good.” I think this can be a very dangerous approach, often formed by masculine and a cis-normative values, a one-way way of looking at the world, without noticing the specifics of a certain place. I do wonder often, how can we be more vulnerability and have courage to say “I don’t know,” and working together with the communities to “figure it out”?

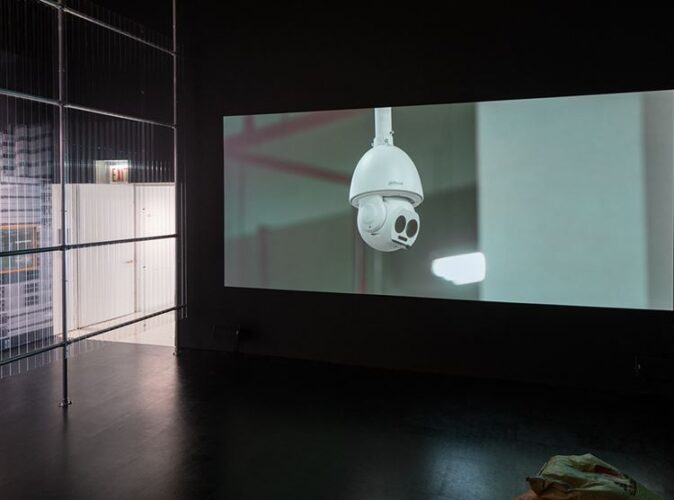

The image chosen by you for this year’s Autumn School of Curating, organised by Cluj Cultural Center and the Art Encounters Foundation, is undoubtedly well-recognized in the contemporary art scene. It features an artwork by Sun Yuan & Peng Yu from the critically acclaimed group show, aptly titled “Tales of Our Time,” which you co-curated at the Guggenheim Museum in 2016, alongside Hou Hanru. In this artwork, a re-programmed industrial robotic arm, reminiscent of a medical apparatus, pierces through its center with a fluid that resembles blood. As I read, after three years, the robot’s movements gradually slowed down due to a lack of maintenance, finally being unplugged as it failed to fulfill its purpose. It seems that the artists’ perspective on the implications of technology in our lives is quite evident here. How about you? Are you a techno-optimist or a techno-pessimist? I understand that things are rarely black and white.

This artwork transcends its exhibition context and has taken on a life of its own. The story you mentioned, which was read on the internet, is not entirely accurate in the sense that it doesn’t represent what actually happened to the artwork. However, it’s interesting in terms of how viewers chose to relate to it, attributing human emotions and feelings to the robot, treating it as a child or sentient being in need of care. This personal perspective reflects the way we often engage with technology today. The version of the work commissioned for the Guggenheim exhibition was later dismantled and now resides in storage. The version exhibited at the Venice Biennale is a different one, shipped directly from China by the artist.

Am I a techno-optimist or a techno-pessimist?

Since I was little, I was always very into all sci-fi things, and the possibilities offered by technology to portray that imagination. I have always imagined that I could live in the ocean or the outer space, and from this point of view technology offers multiple possibilities for implementing a certain utopia. Pessimism has come in, rather because of the political and social implications, when the potential of technology is taken up and put to the service and interests that serve not imagination but rather power and control.

Also, while studying in San Francisco being so close to the Silicon Valley I was able to see the attitudes there towards technology. It seems that everyone only thought about having a start-up and making piles of money out of it, so this is another drive that promotes technology as totally opposed to the open world of imagination. I am also curious of a different perspective on the evolution of technology and its rethinking through art practice, especially in a post-pandemic context, when I realized how disconnected we are and can be from our own body. I have observed how the tradition of conceptual art has somehow placed craft—to make things with one’s own hand—on an inferior level. And I see in the post-pandemic context a return to craft, to its connection with the body, with what we do with our hands, precisely as a response to the increasingly immaterialized nature of technology.

Can you share some details about the subjects and structure you’ve prepared for The Autumn School of Curating? Additionally, one of the program’s key features is your authority to invite anyone you consider relevant from the cultural sector, be it artists, curators, researchers, etc. Could you elaborate on this aspect?

I have prepared some topics that are also part of my current research. We will also touch on trendy themes like AI and technology impact, but what I also want to propose a broader rethink of technological cosmology. I think our modern and contemporary understanding of technology is based on a genealogy of Europeans scientific tradition, a legacy coming from Ancient Greek cosmology, where fire (widely recognized as the first technology) was given to humans, and so civilization arises. But what I want to bring up is that there are other mythologies and cosmologies that gave birth to different kinds of technological thinking and practice that are different from what we know now and yet lost their relevance over the course of history and human development. These cosmology and technological thinking might be less deterministic and rather function as gateways to possibilities. For example, we will discuss the subject of Cosmism.

You have received training and worked both in China, your home country, and in the United States and various other Western countries. However, your focus has often been on artists and practices from the Greater China region. In this context, what are your thoughts on Piotr Piotrowski’s proposed methodology of horizontal art history versus the vertical approach imposed by the West, characterized by its specific styles and practices?

Definitely Piotrowski’s proposed methodology, given around 10 years ago in context of the European Avant-Garde is a crucial one in today’s cultural studies. What I also want to bring to the table in this context is the concept of “transnationality”, as a necessity in a current, contemporary approach to curatorial practice, emphasizing the role of the curator in constructing the narrative of a collection.

What are your thoughts on the growing interest Western institutions, both public and commercial, the educational sector, and the broader art world, have shown in the Global South in recent years? Do you believe this interest primarily stems from the social potential of such practices, or is it merely a new cultural fascination, poised to be translated into new products?

Regarding West-East, or North-South axes I always try to have a non-binary attitude, not to place myself on the classic European or Western liberal position, which condemns what happens in other parts. I have colleagues and peers who live and work in both parts of the world, and who have different experiences and see things from different perspectives. I think the discourse on the Global South is definitely an urgent one and it engages many historical legacies and debts, as well as future possibilities. I do think your point is worth reflecting in depth as echoing with what I said earlier about this “neo-colonial” risk that corresponds to what you call “cultural fetish”. Here I would like to quote Trinh Minh Ha and her concept of “looking with” instead of “looking at”.

You’ve worked in both independent art institutions and internationally renowned established ones. How do you approach exhibition programs and artistic selections based on the type of institution you’re associated with? Specifically, I’m intrigued by commissioned artworks, which represent a relatively new practice in our country. How do you address the responsibility that comes with choosing a work to enter a globally recognized collection, essentially integrating it into the canon of art history?

I believe that these definitions should not be in opposition. Personally, although I support grass root movements, I believe that real and fundamental changes have to happen from top down and inside out. I have little faith in the viability of approaches such as “stand outside and do institutional critique”, because it leads nowhere. It is ideal, even from a pragmatic point of view to legitimize the curator’s job, to be able to secure an income – if you do not come from a privileged background – and privilege can mean many many things: money, gender, sexuality – to be able to work legitimately and to be recognized as a curator professionally. And yes, in an institutional environment you face different challenges, you need diplomacy skills, even bureaucracy skills, but that’s a possible way to instigate change, by integrating yourself into an institutional environment and trying to change it from inside, and still keeping the independent nerve and curiosity. Of course, there is also the risk of acclimatization and start to feel too comfort in a safety zoon, but it depends on each individual. So no, independent and institutional should not be in opposition. I would like to in fact advocate more mutual understanding from each side and create more opportunities for effective communications.

Regarding commissioned artworks, yes, it was definitely a challenge. “Tales of Our Time” was the result of my first institution job when working at the Guggenheim, some of the artists already had museum shows and are in museum collections, some of them don’t. I would say that the process was like an ongoing negotiation, and you have to constantly convince people why this or that artist is important in a given context. So, 40% is about artistic content and 60% about management, and interpersonal politics. And sometimes you receive opinions by people that are working with different priorities, and that’s when you realize that is not just one standard, but there are different standards, if 100 people are coming in there will be 100 standards. And I really think in being a curator you also have to be a good negotiator. And also have to negotiate with artists to, not just the staff people, because also sometimes the artist comes with really unrealistic requests regarding payment or implementation of the project.

Your course title, “For a Multitude of Futures,” seems somewhat opposed to Okwui Enwezor’s “All the World’s Futures,” which felt more like a conclusion to the late Anthropocene era. Your title appears more open-ended, emphasizing its social foundation. Could you shed some light on this? Is this a particular topic you are currently exploring or interested in?

Your observation is certainly interesting. I had never considered this parallel before, but I can see it now what you meant.

Here, technology sabotaged our interview, and the perspective remained open and undetermined: for a multitude of futures. I will have the opportunity to respond to this open question during the Curatorial School.

Open call for applications until October 6th.

POSTED BY

Horațiu Lipot

Horațiu Lipot (b. 1989, Alba Iulia) is a curator and cultural journalist. As of 2021, he works as an independent curator, collaborating with venues either from the ON or OFF art- scene in Bucharest, ...

Comments are closed here.