My wishful projection for when I will be done with this article is to capture in a swish pan move the most thought-provocative events and exhibitions that I took in from my most exciting artsy-related errand so far. As I am writing this, I realize I have troubles switching on and off memory lane as I need to move from one gallery to another, from a face to another, from different ideas that have been debated here and there. Thus I feel impaired also by my voyeuristic stand into a Polish art scene that requires a longer immersive investigation. With the risk of a undertaking a mere surface glimpse in order to make the readers ‘see’ something that requires not only eyes or words but also presence, I will present in this first part of the article some exhibitions that engaged with the generous topic of interaction between man, matter, technology and landscape.

The initial itinerary plan was to start with major art institutions and from there move to lesser known or alternative spaces that I have hoped to find in abundance in Warsaw. This part will be tackling the art scene from Silezia and Krakow as I had the chance to be there during the city’s gallery weekend.

Therefore the first logical step was to see what’s in at The Centre for Contemporary Art at Ujazdowski Castle, Warsaw which hosted Cezary Poniatowski’s Kompost [Compost] exhibition in the Bank Pekao Project Room, curated by Szymon Zydek. As many exhibitions that I’ve seen this year, in England and abroad, it made suavely vacuous allusions to trendy posthumanist terms like, for example, that of compost which has been theorized by Haraway as a peristaltic commingling of human and kindred in the snuggly yet messy pile of mud, detritus and waste. I say vacuous because oftentimes these exhibitions succeed in providing mere allusions to ideas they claim to embrace without reflecting an in depth rumination. Yet I assume the fact that ideas floating out there in the ‘world’ (a flow that always follows a western wind) are prone to being commodified into academic and aesthetic capital is not new to our readers here at Revista ARTA. And then I say suavely vacuous, and the adjective here is more powerful that its referent, because, at the end of the day, they do work in creating something close to a sense of eeriness, of seductive oddity and newness which at least kindle debates over which are most needed in our times of anthropocenic and economic dismal.

The project room recreated an environment of rotting matter patronized by a giant horned God-Dj-steward: a mixologist of the smoke, noise, and heat inside. Interplay of the monumental and the trite, that both annulled and celebrated each other, the exhibitions moved towards being a parody of some tendencies to mythologize the past – a phenomenon that spans from naive historical gizmo series to very recently proliferating far right movements. Some occasional mythological sublime that might have been awakened by the exhibition were vented here with informed yet branded humor by the imposing image of a mad gardener of trash – probably carrying on his hand a huge meal of historical s*it and thinking about recipes of equally smelly composted futures. The more time you spent there, the lack of light and sometimes the smouldering air made room for a rather inebriating experience as you navigated the space with a worry not to tamper with the light-emitting boxes on the floor. It rendered the kind of feeling you get when you fumble your way out of a crowded nightclub, overly aware of your own drunkenness and the self-perceived difficulty in traversing obstacles.

Uncalled for stream of consciousness alert: the anti-climactic noises stemming from Lubomir Grzelak’s sound installation – that sampled together noise/techno/classical music tunes added up to this carefully staged eeriness. As I was moving through the tarry chamber of imagined decomposing matter I felt myself turned into more of a probe head- not sure if of the deleuzian sorts – but surely one of a fumbling tendril searching for some meanings to which to attach or detach, to create paths in deciphering the exhibition.

These first impressionistic scribblings of mine recorded under the careful watch of the friendly horned statue acquired some new nuances when I attended the artist’s and curator’s talk hosted at the Ujadowski Centre. As Cezary explained, his work drew inspiration from his painting motifs whose temporal processes of production he tends to spatialize in his installations. In this case he staged a crude theater of what was going on inside his head when he thought about creating a certain painting with all the inner psychic processes it implies: gestation, rumination, contamination, decomposition, decay, transformation. Outside this anthropocentric scenery and postumanist references that I guessed but, as I understood later, were not the primary rationale of the exhibition, he tried to convey the cannibalistic metabolism of art, reality and creative processes- the loopy, circular/stages bursts that define art production.

I found a similar exploration of the theme of matter transmuted into the aesthetic means of a singular descriptor (either in the fermenting frenzy of its decomposing state or its coarse, brute instantiations into coal and petrochemicals) in the following exhibitions that I got a chance to visit in Katowice and Bytom. Coal for example has shaped both landscape and human activity for nearly two centuries in the lower Polish Silesian county. In Katowice and Bytom I did not fail to notice how artists are trying to mining their way thorough a rather precarious art ecology. Whether they succeeded in doing so or end up wandering off the same beaten tracks was a matter of private initiative and larger institutional framing. When I arrived in both Katowitce and Bytum I got a clue on why the words Polish Detroit are thrown in the air, casually, whenever people are talking about Silesian towns. I hope that this would spare me many words in describing their history as former lucrative industrial centers turned into dysfunctional economies turned into places were discourses about reboosting the periphery with creative capital.

The Museum of Silesia opened in a former coal mine in Katowitze, the county’s capital city, with co-finance from the EU’s Regional Development Fund and the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage’s assistance. As their website informs us the museum was settled as to serve multiple purposes: library and reading room, an auditorium of over 320 seats, an educational area for children and a temporary exhibition space- which kept the non-slatted section of the original mine so that visitors could overlook from above the exhibitions on display before descending into the gallery. As many would wish for Romanian towns (*less successful in attracting EU funds and focused minds to develop such projects) the museum acted on an impetus of a kick start revitalization of an area important for the country’s cultural and natural heritage. And, I would add, a hopeful wish that in doing so, it would bring in a capital concentration over a background of massive unemployment and decaying community bounds brought about by the bygone era of lucrative coal extractions. Like run-downed miner cities elsewhere it has become a preferred space for (often right wing) politics to advance their promises of reconstructing the mines, of bringing back gratifying jobs and the dignity of the mining profession. How unprofitable and, in the end, dangerous is to fuel hopes over the now outdated use of coal remains a confrontational question for said political irresponsibility.

On the side, there is always going to be a twofold response to projects of the sort: one embracing the other rather scrutinous. On one hand, it is encouraging to see funds directed towards new infrastructure for art in times of indefinite recession and massive cultural cuts. On the other, I cannot help to wonder what sort of solutions do they really bring in except that of adding up to an existing unstable, poor and disenchanted ecology, the precariousness of art labor: the unconsoled striving of kunstarbeiters chaperoned by a cohort of still enthusiastic un(der)paid interns. In a statement for which he gradually lost enthusiasm later in his life Pontus Hulténs wanted to do just that: to bring people in a community center opened for all and hope for a time where more and more would be freed from subsistence living and free to wander inside his massive cultural multiplexes. Or, as he referred to his ambitious Pampidou center: “At the Beaubourg, you have a whole series of overlapping things to do, and therefore the area becomes much more active. It’s more like a railway station… It’s the theory of the flexible magic box, which includes the piazza. Nothing is ever static, and nothing is ever perfect.” For it is within the protean potential of white walls that the promise of an art ever free from the underworkings of capital recedes to mere illusion.

It remains a wish that the Silesian Museum brings in clear, calculable benefits for people living in perpetual unemployment and where the often unbearable slowness of change makes people vote for very unpalatable agitators. Otherwise Katowice has been served that brand of alleviating anti-depressants that fail to fight the psychic and environmental causes for such deflation of enthusiasm. As effective in changing lived conditions like Fedde Le Grant’s flashy song: Put your hands up for Detroit! All the while art continues to put its hands up for mushrooming Detroits everywhere and, at some point along the process, fails to avoid contagion with its endemical causes.

Overlooking the Contemporary Art Gallery (BWA) and the Silesian Stadium, both built during communist times, the Museum hosted, along its permanent historical collection, three exhibitions. At the ground floor a photography display that included works of Vladimír Birgus (from the famous FAMU, Academy of Performing Arts in Prague). At the same level, a monumental sculptural installation of Daniel (Dani) Karavan which inspected the interpenetration of negative reflections by taking inspiration from some lines somewhere in Hamlet: “somewhat as a mirror of nature, / to show virtue own her face, anger alive her / image, and the world and the spirit of the age form them.” To clear the air imagine a chamber hooded with massive silver mirrors where visitors could explore the space and stare at (but not climb) white ladders that pierced and sectioned their reflections.

The exhibition I Am Not a Dog in the largest space was devoted to outsider art. One has to wonder if it still makes sense to call something outsider or peripheral when it is so neatly incorporated in the circuit of family friendly exhibitions such as this one- although we have been kindly warned by the guide that this is no exhibition for kids to see due to the occasional display of o, shocking, nudity and sex scenes. Of course it has become normalized practice to tarry on the marginal, peripheral de-territorialized production as a sign of authentic, institutionally unmediated art. Rather or not one takes it as a themepark display of freaks or a display of unskilled geniuses I did appreciate however that they chose to incorporate some works which are really hard to defend due to their sensitive content. To be more precise I was engaged in contemplation with two paintings which depicted a defenseless white woman putting on perfume being attacked by an (oh!) brown hand hand holding a knife. The other philosophized on how the jungle of consummerism turned us into savages – again very subtly portrayed with very recognizable aboriginal features. I found an ounce of sympathy for the artist consumed at once by baudrillardian critiques of reality under neoliberalism and racist imaginaria. Art that can be naively distasteful in that way too.

Under a 0 degree temperature in late April and mushy grey clouds I was accompanied by my fellow resident from Szum Magazine, Piotr Policht, and a young Belarusean curator, Vera Zalutskaya, to the studio of Bartek Buczek a graduate of the Academy of Fine Arts in Katowice and owner and bookseller at Un-Required Readings which does play a part in his work in his often use of bookish, literary references. For example his paintings often depicts trickster characters-who as mythological demigods contain at once contradictory traits, from intelligence to foolishness or perversity. As a figurative tool they are very lucrative in criticizing or attacking the omnipotence of dominant paradigms. Through his multiple poses he/she/it is a bearer of subversive meaning, but in the same time an aesthetic and narrative tool for telling stories. Narration and subtext, as Bartek has told us, hold central locus in his work.

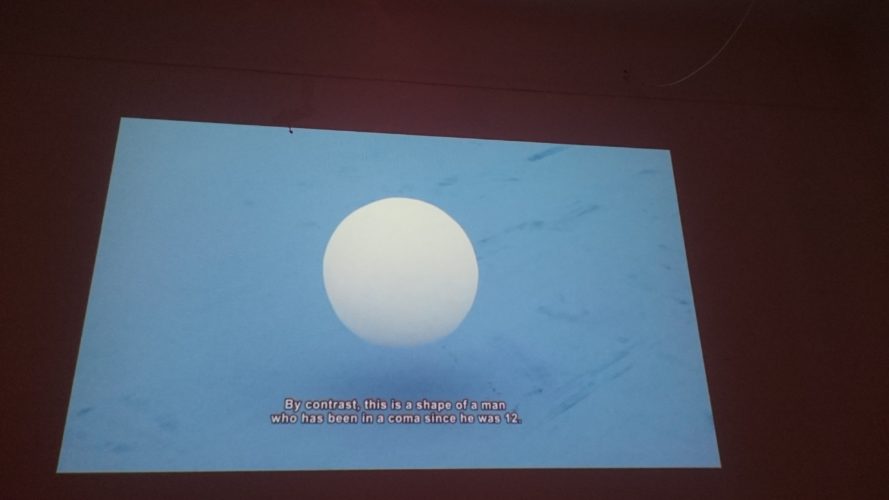

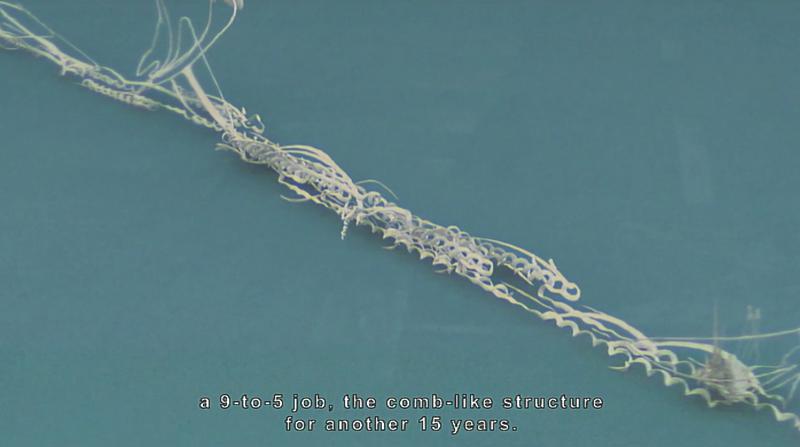

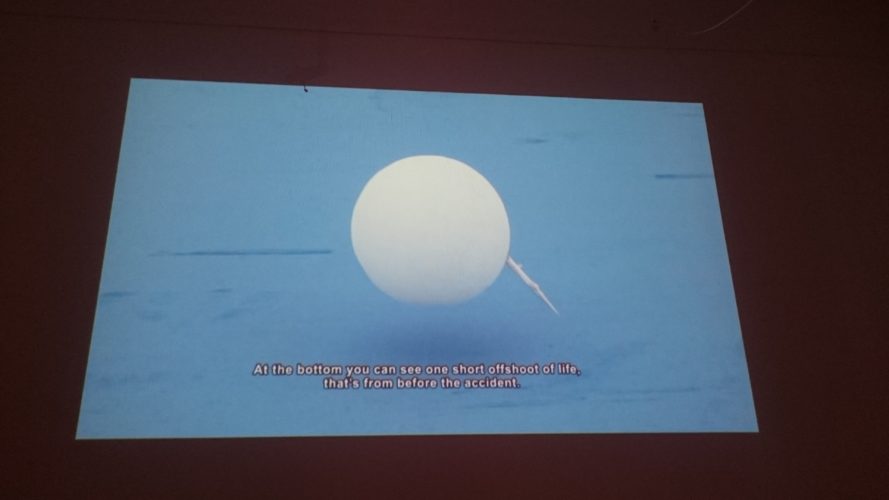

We woke up early the next day to head to the Museum of the History of Photography for the Non-Existent Exhibition Spaces by now celebrity Polish artists Norman Leto, who, ten years after his debut, returned to Krakow, the city where he has done most of his early work (painting, photography and new media). The title of the exhibition reflected the artist’s juxtaposition of digital environments into existent and physical exhibition spaces using 3D, data collection and a series of algorythmical sequences that he has had previously created. The exhibition displayed samples of Leto’s early work- like for example, Rezistentza (2006) when, long before the normalization of self display and self distribution of selves on social media, he used a camera to document every event of his life, in an act of almost annihiliating self-surveillance. The exhibition also included prints and extracts from the film The Sailor which has brought him widespread international praise. In it, Leto used data collection of famous and ordinary people to generate digital life shapes of say: Joseph Stalin, Geraldine Chaplin, his own family members, Michael Jackson etc so as to make a case on how visibility and traffic of images online generate either complex and complexifying shapes or, simple, fragile, boring formations when they enter meatspace. Life is conceptualized in these works as a chimeric assemblage of data: gathering, compounding, sublating. Leto welcomes rather obstinately his audience: “Now I’d like to talk about joining of the shapes in generations, in generational sequences. I hope you are following what I’m saying and I hope I am expressing myself clearly because it costs me a lot of effort, so if you’re not following, or you’re not interested-just go…What did I day, Nel, what did I say? Excuse me for a moment… because this is not fucking Animal Planet, these are real visualizations, have you ever heard about true visualizations? about true screenshots? Mind your own business while I’m working!”

From the Museum of Photography we headed to Bunkier Sztuki Gallery of Contemporary Art in Krakow an important contemporary art a landmark for Krakow art hosted in an accomplished example of modernism.

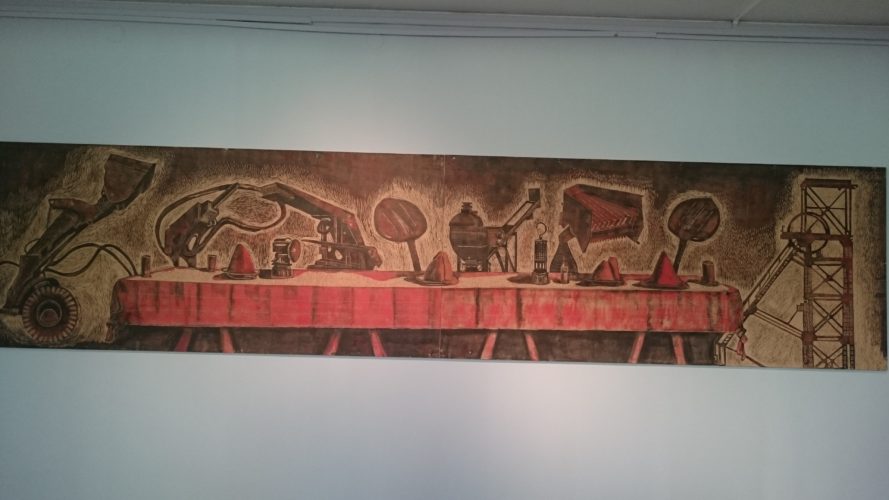

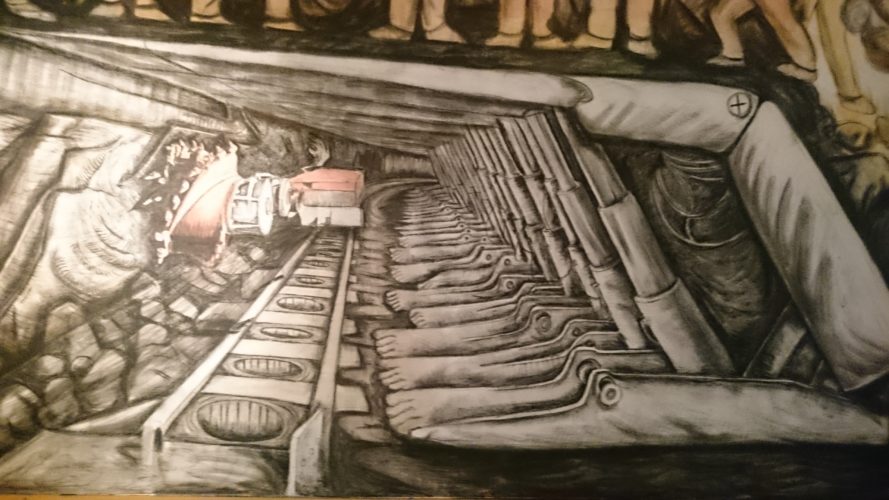

The exhibition Harbingers of Chaos by Indian artists Prabhakar Rachpute and Rupali Patil nosedived discussions surrounding our anthropocenic times straight down into the underground of the mine. For, in the end, it is inside the darkness of the underground and not the unwelcoming outerspace that we might seek refuge when its surface will be haunted by coming ecological nightmares. Huddling there in the dark, sharing our body temperature and resources, we might finally start to renegotiate human value and overall sit there in the pit and think about our own foolishness. More so as we have to share the space with increasingly intelligent machines that might accelerate our present troubles. Inside today’s high-tech mines disassemblied human hands will embrace the artificial hands of the machines.

The exhibition also investigated new regimes of affect and spirituality now that miners trapped along in the Eath’s insides stop praying to Santa Barbara for a slow death and instead have to rely on the mercy of inhuman machines. Although the exhibition leaked away some glimpses of nostalgia towards more traditional forms of mining and more serene (although part fictional) past when mining built strong communities and a sense of working class identity (masculine for the most) it did shore a possibility towards a geopoetics of the underground. For example, the sculptures on display created a visual magical realist chutneys of mutant man-tool-animal assemblies. They managed to thick the really thick box of object oriented ontology and conveyed instant references to tool analysis where objects cease to be defined by their functionality but rather their mutual activity with the human hand and all their surrounding conditions.

From the Harbingers of Chaos we moved to see Justina Medrala’s The Machine Was so Impressed It Collapsed Into Itself, an exhibiton held in the basement of the Bunkier Stzuki. Medrala’s work constituted another example of working alchemically with ephemeral materials: smoke, coal, wax, blood as to express the fragile, asymmetrical relationship between humans and machines. The artists used traces of smoke (from lit candles) on wittingly installed canvases to trace down a memory of a dream in which she was crushed over by a machine: “A voice uttered in my dream. I was surprised with the absurdity of it, but at the peak of the mountain I really did see a self-proclaimed machine for making nothing that was folding in half. I think it must have been watching me for a longer time and it collapsed under pressure. Echoes from Viktor Tausk, who investigated forms of psychosis and schyzophrenia that involved the patients’ imagining of ‘influencing machines’ shortcircuited my reception of Medrala’s work. The passage that came to my mind was that in which he explained that patients describing their visions of malevolent machines in most accurate detail have a limited understanding of the causes that generate it “in cases where the patient believes he understands the construction of the apparatus well, it is obvious that this feeling is, at best, analogous to that of a dreamer who has a feeling of understanding, but has not the understanding itself” (Tausk). Medrala’s work goes beyond a mere clinical confession in which the psychoanalyst always has an advantage over the interpretation of the psychoanalytical event, often overlooking the intrinsic absurdities and unrespresentable aspects of dreams. She recounted her story in subplots and digressions so as to archive the processes of memory searching that comes along when one tries to carve the shape of a dream in matter. If, as stated in the curatorial text, “a real machine is the source of the shape-forming smoke” (Krysztof Siatka). The basement was a smart curatorial space, even for its sole psychoanalytical connotations.

As I said at the beginning it has proved rather difficult for me to try and organize, thematically or even chronologically everything that I had the chance to experience during my stay in Poland. It does however prove that is has been a much welcomed overload of heartening exhibitions and equally pleasant people met along the way.

For the second part of the article I will return to our main Warsaw headquarters.

Georgiana’s residency was possible thanks to the generous support of AFCN, ICR Warsaw and the Polish Institute in Bucharest.

POSTED BY

Georgiana Cojocaru

Georgiana Cojocaru is an art writer, curator and editor living and working in Bucharest. At the moment, her research practice focuses on generic aesthetics, poetry in the Anthropocene and fictionalisa...

Comments are closed here.