And then, unexpectedly, the last evening at the Casa Boema restaurant brought together virtually everyone who has contributed to the city’s art rising to fame across Europe. Even speaking of a kind of world fame would not be an exaggeration, of course, depending on how we define the world, which is not so self-evident from an East Central European perspective. So, as I was saying, there we were, on Good Friday, before Easter, sitting around a table – the people in and around Plan-B Gallery, namely, Mihai Pop, the founder and engine of the gallery that has, over time, come to focus more on Berlin than on this town; Adrian Ghenie, the most famous Eastert European artist today, who lives and works in Berlin too, and whom we can certainly call a superstar, with his works going for stellar prices on the secondary and tertiary markets these days. Diana Marincu is also here, a young curator in charge, among other things, of Plan-B’s activities in Cluj that take place mainly in Domino, a project space on the ground floor of the Paintbrush Factory. And here is Corina Bucea, the head of Fabrica de Pensule (the Paintbrush Factory), who is quite busy at the moment exchanging SMS messages with a group of people stuck on the motorway somewhere in Italy, on their way to Venice – Corina is in charge of Romania’s participation in the Venice Biennial, and seems rather worried as the people on their way to Venice are likely to have to spend the night somewhere on the motorway, and so the project in Venice will start with a delay. And here is Ciprian Mureșan, who is not world famous, ‘only’ highly renowned in the region, popular in Hungary too (click here for artPortal’s interview with him).

(without a space)

Obviously, it was not possible to meet everybody while in Cluj. Almost by total accident, I had the chance to speak briefly with one of the most promising new artists, Alex Mirutziu from Sibiu, but the few words we exchanged were not enough for me to really grasp the essence of his singularly professional videos and powerful performances. And unfortunately, I did not have the luck to meet him again. Meanwhile, there are other people sitting around this long table, maybe less legendary but still very spirited and influential actors of Cluj’s art scene: here is Flaviu Rogojan, a young artist and organiser, speaking in German and English with a German journalist who is here to explore the myth of Cluj for a German magazine. With two other artists, Flaviu operates AiciAcolo, an artis-run gallery without a permanent space. The project appropriates the spaces where it pops up placing a neon sign on the wall.

Sipping on a glass of Prosecco, Șerban Savu is here, the artist who shares a studio with Mureșan. While their artistic worlds are light-years apart (Savu’s is figural and Mureșan’s is conceptual), the two artists are clearly close in life. And then, there is a young man, in tracksuit top, with a few beers already down him. It is Dan Beudean, in a heated discussion with a girl in glasses, with a huge pile of meat in front of them. The girl is designer Dana Ștefănoiu, an active player in the city’s maker scene as well as in art for education. With many others, she participated in Pata-Cluj, a social-art project to support the 300 Roma families living in Patarét (Pata Rât), the city’s slum area – or let us be precise: the city’s landfill. The project focuses on integration or rather reintegration, as it was the city that evicted most of these families to the periphery of the city. When I arrived in Cluj, Dan Perjovschi was in Pata Rât, drawing on the walls of the shanties with kids and adults, while local representatives in the town hall were making fiery speeches in a debate on a housing project funded by the Norway Aid programme. The project would help the families move from shanties into real houses, with humane living conditions, which would be an immense improvement for the people of Patarét, living universes away from the Boema restaurant.

It is getting close to midnight. Easter Sunday is around the corner. All the people who are here came from the Sisters, where the guys from Germany had gone straight from the airport, and where a female DJ mixed the tracks. Mihai Pop, in a snow-white shirt, sat at the head of the table, with a journalist on either side, the German guy on his right, and on his left a French reporter. The magazine the bearded Frenchman works for pays him a field trip to an EU country every month to write about what he sees there. He is here now to explore the myth of Cluj, and with the German journalist they will leave here for Hungary the day after tomorrow. He asks me if I can give him contacts of people to talk to about the Central European University (CEU) demonstration, and to artists involved in opposition activism. But then our voices get lost in the noise of the restaurant.

(the people who got fed up)

“I think it is useful for people to be aware that they can never know for sure how they would respond to things that happen,” Ciprian Mureșan observes in the interview with artPortal mentioned above, and his words have often come back to haunt me recently. I left Budapest just a few days ago, the morning after the mass demonstration with some 70,000 people marching, and right now, it feels good to be Hungarian here, as everybody knows about the rallies in the Hungarian capital and everybody wishes us success. And of course, I respond that a few months ago it was us who were watching the news reports of how tens or sometimes hundreds of thousands of people marched almost every night in cities across Romania to protest the manipulative practices of the government. The people who got finally fed up – and there was a lot of them all of a sudden. We knew how it felt to be fed up but we could not imagine that those numbers of people could ever march in Hungary. And while we had no idea what would have to happen in Budapest for tens of thousands of people to rally, Bucharest, Iași and Cluj seemed active cities, ready to respond, ready to organise themselves. And then, all of a sudden, it happened in Budapest too: the government’s attack on an international university was the last straw before people took to the streets chanting “we have had enough”.

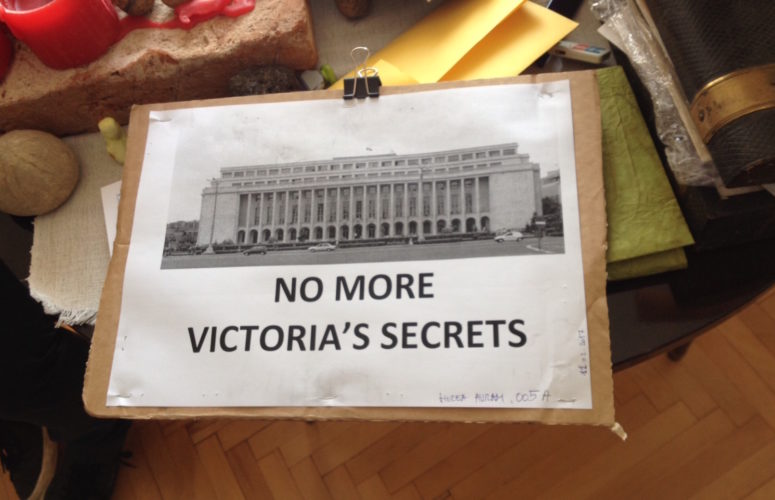

On my first day in Cluj I find myself in a loft on the city’s main square, with a breath-taking view of the hill over the city. I am sitting here talking with art historian György Sebestyén Székely, head of Quadro Gallery, who has turned one of his rooms into a temporary museum. He collects banners, signs and other accessories used in the recent demonstrations, and also personal stories related to each object. “An object and a story that goes with it,” he says, adding that the real challenge is not so much to collect the accessories because everybody is happy to give them. The problem is of museological nature, namely: How can you collect the present? How can you archive and study what is happening right now? All the more so, because while the signs are funny, witty and inspiring – one of them was held up by the actors of the Cluj Romanian Theatre on the stage after the performance of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest and said “We die on the stage but resurrect in the street,” referring to the demonstration to be held at 10 o’clock that night –, feelings and opinions vary about all that happened.

In a night session, the governing party wanted the parliament to pass a new decree to water down the anti-corruption law by decriminalising minor corruption offences. While the Romanian anti-corruption authority, the DNA (Direcţia Naţională Anticorupţie) launches an investigation even if they find just a box of matches that an official may have received under doubtful circumstances, and many agree that the directorate’s operation should be made more realistic, the government’s move was still seen by people that the regime’s aim was just to legalize corruption. I could say I wish we, in Hungary, would have the same problem of how to judge the anti-corruption agency’s level of strictness, but I am not really in the mood these days to make jokes about the level of corruption in my country, and right now, we have no idea how such a directorate works in a democratic country. At the same time, we cannot say that the situation in Romania is ideal either. In a way, both countries are under the same Eastern curse, we take the same place in Transparency International’s corruption perceptions index. While DNA prosecutes corrupt politicians, it is also a tool for political manipulations. And the protest rallies were also not purely about democracy but about the democracy of the white Christian middle class – as an analyst points out, the marches can also be seen as the revolt of middle class professionals against an attempt to restore patronage democracy. In Budapest too, it was urban, middle class young people with western type democracy ideals that started the rallies. However, they did so in the name of liberal ideas, and the events were characterised by openness to and inclusiveness of other classes. It would be essential that people who are addressed only by the trash media, those who have no access to the urban middle class discourse, and who have no idea what the Central European University (CEU) is or what NGO’s do, should also be included. The media, communication channels, the accessibility and free distribution of sounds and images are essential for that level of organisation, but in Hungary, free media space has been narrowed down scarily, to three or four media and the communication bubbles of Facebook. At the moment, Hungary is 25 places behind Romania in the World Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders: Romania is 46th in the list and Hungary 71th, with Norway ranking at the top, and North Korea 180th.

(it’s about how you look at it)

Corina Bucea mentions the use of symbols, the national flag and the anthem as things she found somewhat strange to see in anti-corruption demonstrations. I explain to her that in Hungary, the national flag and the anthem are just being re-appropriated, and fortunately, the notion of what is national has also been re-appropriated from exclusive use by the extreme right and chauvinistic governing parties. Obviously, all these questions do not take away from the wit of the signs in György Sebestyén Székely’s collection, and it is also refreshing to see ones with international references, such as one that went viral on Facebook. It says “No More Victoria’s Secret”, however, it does not refer to the women’s lingerie brand but to the Victoria Palace in Bucharest, a modernist building that serves as the headquarters of the government.

As regard signs to be seen in public spaces, well, that is certainly a problem area. Here I mean town signs, which are still not bilingual at many places. In April, a group of citizens won a case against the city at fist instance for the city failing to comply with a 2002 local government decree, and although the Hungarian minority exceeds 20% of the population, the local government has not installed bilingual signs. The public space interventions of the Musai-Muszáj group keep calling the public’s attention to this fact. At first sight, one could say Musai-Muszáj and its founder István Szakáts are similar to the Hungarian Two-tailed Dog Party (Magyar Kétfarkú Kutya Párt – MKKP). But in fact, this comparison would miss the point. First of all, the MKKP is a party, and although it carries out ironical, or more precisely, refreshingly funny actions, it is in strong opposition to the government. Meanwhile, Szakáts does not oppose the ruling power (nor is the ruling power in Cluj like that in Hungary) but instead, he keeps putting the establishment to test. Sometimes he cooperates with the administration, as the city’s leaders occasionally ask him for his opinion. Or rather, he takes a position where his voice gets heard. He refuses to be called an activist (“the suffix “-ism” kills the word it is attached to,” he says), nor is he an artist (“art is a truth regime”, he says). Instead, he defines himself as an active citizen. A member of the Altart Foundation, he is among the organisers of the Pata-Cluj project mentioned above. He also participates in the citizens’ fight against appropriating green areas for construction, and he also partakes in provocations, such as the kidnapping of a Santa Clause statue from the city in 2015, and demanding a ransom: Santa Clause gift bags for charity. While even bilinguality is a problem, Musai-Muszáj fights for trilingual signs “Cluj-Kolozsvár-Clausenburg”, and places them here and there. On top of that, he hacked the city’s bus network putting up lenticular signs that said in Hungarian and Romanian: It’s about how you look at it.

It is, indeed. In Hungary, most people still associate Cluj with Gheorghe Funar, its long gone ultra-chauvinistic mayor. But in fact, by now, Funar is no more than laughing stock there. You cannot find even a trace of chauvinism in the discourse of the city’s progressive young and less young intellectuals. On the contrary: everybody around the table in the Boema told me a few sentences they knew in Hungarian, and I met a Romanian curator who is learning Hungarian because he has so many ties with Hungarians that he simply has to learn the language. Even if only on the level of slogans, Emil Boc, the city’s mayor likes to point out that Cluj is a multicultural city. All of a sudden, another country springs to my mind, Serbia, and the city of Novi Sad, “Újvidék” in Hungarian, or Neusatz in German, where in the last days of Milosevic’s rule it was strongly disadvised to speak in any language than Serbian, but by today, the city’s trilingual tradition has become a matter of pride there, with restaurant menus in Serbian, Hungarian and German, street names from the days of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy coming to be used again, with signs with those old street names placed across the city. At the Újvidék (Hungarian) Theatre, full houses of Serbian speaking audience sit through the performances of Neoplanta, a play about the multi-ethnic city’s blood-soaked history. Is it because with the spectacular failure of the nationalist narratives appropriated by political chauvinism, local identities are becoming increasingly important? Maybe. Perhaps because erecting turul bird statues on the main squares of every Hungarian village has not improved anybody’s living conditions one atom. Nor did the fact that many years ago, garbage cans and benches were painted blue, yellow and red in Cluj. This city has a clearly international character, connected to Europe thanks to budget airlines. Of course, those airlines would not fly here if there were no demand. But there is…

Part 2 coming soon.

Gergely’s residency in Cluj was made possible thanks to the generous support of AFCN and the Hungarian Institute in Bucharest.

POSTED BY

Gergely Nagy

Gergely Nagy (b. 1969) is a journalist, editor and author who lives and works in Budapest. Currently he is the editor in chief of Artportal contemporary art website. His main fields of interest are cu...

artportal.hu/

Comments are closed here.