“The Undisciplined Eye. Everyday Life Beyond Narration”, at CEREFREA Villa Noël, is the exhibition that concludes the residency project of three artists, Nicole Hewitt (Croatia), Sonja Jankov (Serbia) and Romana Schmalisch (Germany) and which compiles the items they gathered in their exploration of Romanian urban spaces and historical materials, which are confined to three rooms (one for each artist), though not hermetically sealed, the conceptual similarities between them being visible in spite of spatiotemporal differences. Gathering is the key-activity here, most of the objects being in one way or another copies (some are even reproduced multiple times), from photographs and artworks from archives for Romana Schmalisch, to copies of magazine covers and statuettes in the case of Nicole Hewitt, to photos of buildings from Bucharest for Sonja Jankov. Each of them also offers a reinterpretation, a reevaluation in the present of the bigger picture constructed from the historical materials. How then does the research of an outsider integrate and interact with the local and global discourse?

The exibition text on Romana Schlamisch’s room’s door opens with a fragment from Walter Benjamin’s ninth thesis on the philosophy of history, the one in which Klee’s Angelus Novus is interpreted as the “Angel of History”, whose face is turned towards the past (the quote ends here) and sees “one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet”. The artists’ eye also turns towards the past, though, in this case, the past stares back. All three individual exhibitions share a common theme through images, projections, speculations on the future, for Schmalisch by writers and artists of the 19th and early 20th centuries, for Hewitt in the Povestiri științifico-fantastice (“science-fiction tales”) magazines, and for Jankov through the envisioning of the aspect of urban structures in the future, a practice demonstrated by architect Bogdan Bogdanović in one of his lectures, and dubbed “mythological drawing”. Symptomatic of the exhibition’s attitude is the relatively shy reinterpretation of historical items, in whose gathering and conceptualizing lies the strength of the exhibition, in detriment of the envisaging new and desirable futures, in stark contrast to the SF writers, artists and architect cited by the artists.

In Romana Schmalisch’s room, pluralities of visions meet. Side by side one sees exhibited expressions of pure cosmic fantasy, from J. J. Grandeville’s, who imagines a bridge connecting the planets of (what we assume is) our galaxy, and in which the rings of a planet are converted into a balcony, from which the common bourgeois can enjoy the view, and the clouds laden with grand roman-inspired monuments and regiments of cavalry in scenes of German victories throughout from Heinrich Harder’s drawing (Astronomische Phantasie, 1910) (primitive and harmless imaginary colonizations and anthropisations of yet unexplored spaces, though interesting as historical documents), passing through the telephonescope imagined by Camille Flammarion, to modern means of observing the cosmos (such as the James Webb telescope).

In fact, the idea of historical progress as is implied in the exhibition as the continual discovery and assimilation of the unknown, a side effect of which is the disappearance or, rather, the pushing back of fantasy into the next uncharted territory, driving the inhuman yet anthropomorphic beings from unmapped continents to Mars, Venus, and the Moon, and now to the unfathomably far reaches of a predominantly empty universe (that would be one reason for which adventure-fueled or moralizing fantasies such as those from the golden age of science-fiction are harder to come by today). The borders of knowledge and speculation are always being pushed and always separated, yet moving together. The transcripted conversation between the artist and astronomer and astrophysicist Mark Rushton begins by attempting to ground a 19th century vision (the possibility of capturing the light transmitted from Earth into space and therefore viewing life on earth at that point in time unraveling like a movie, imagined by Felix Eberty in The Stars and World History (1846), from which Harder’s work is inspired) on a foundation of contemporary scientific knowledge, which slowly crumbles as the theories become newer and more controversial, ending on speculation on wormholes and stars made of iodine, capable of capturing light from the Earth.

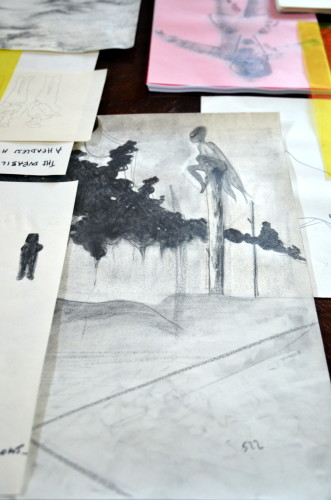

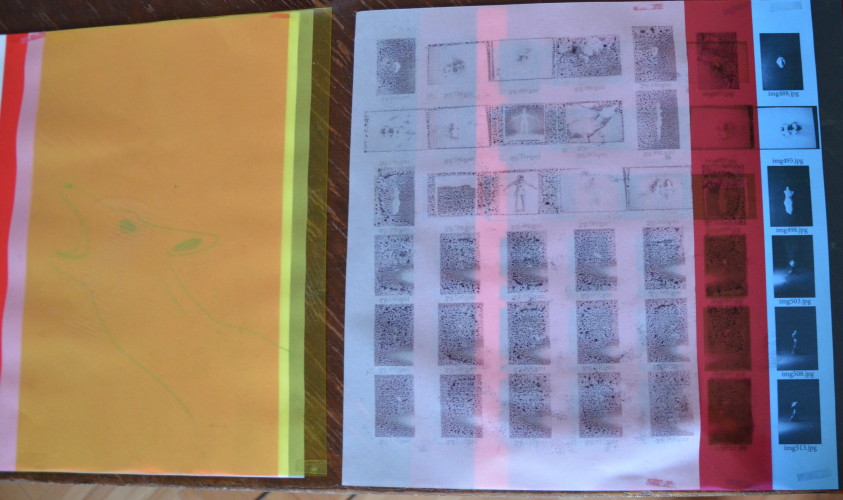

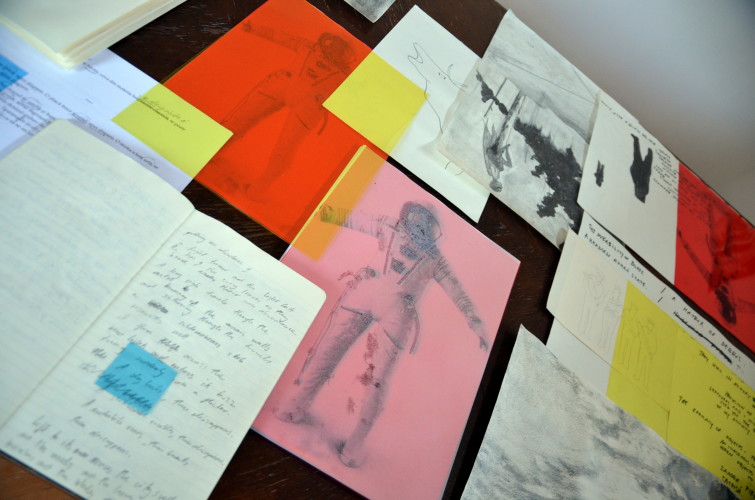

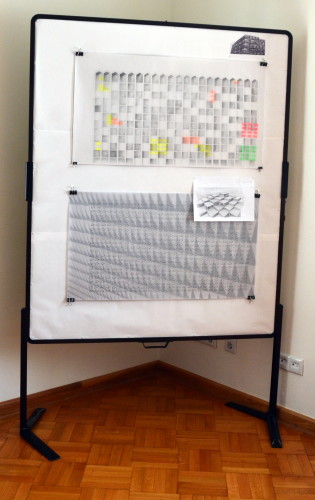

This type of imaginary constructed through the constant circulation of discourse from a multiplicity of sources quickly permeates the collective consciousness, functioning like mythology. Sonja Jankov brings the possibility of dreaming into the present through the conceptual reimagining of our surrounding space by means of the aforementioned mythological drawing, which consists of imagining a building’s aspect in the future (we must also assume a certain attitude of the man of the future towards buildings from his past). Her endeavor was to seek and document examples of brutalism-inspired architecture in Bucharest, also photographing communist monuments. Hers is the room where the interrogation of the past actually becomes concrete in the form of drawing, in which the public is invited to participate, democratically, having the means at their disposal. Nicole Hewitt’s space is also interactive, perhaps embodying the best the image of the archive, towards which all rooms aspire in one way or another: Numerous sheets of paper and notebooks with jottings, scribbles, and sketches, clay copies of Neolithic anthropomorphic statuettes, some seemingly exhibited on the table, others in a cardboard box amidst packing peanuts, drawings after „Povestiri științifico-fantastice” magazine cover art in notebooks, in which only a couple can be seen at a time, the others requiring an effort on the part of the visitor to uncover. Romana Schmalisch’s room appears like the result of such an effort of sifting, sorting and compiling, the objects being exhibited in the window of a cabinet, as in a cabinet of curiosities, without any suggested hierarchical differentiation between them.

Integrated into the 19th and 20th centuries’ global fascination with the possibility of contact with intelligent extraterrestrial lifeforms is Romanian writer Victor Anestin, who, in his 1999 novel În anul 4000 (“in the year 4000”) (a copy is displayed in the exhibition) imagines a contact with an advanced alien civilization on the planet Venus. Though rather than being the conceptual starting point for the exhibition, he is assimilated into it. For Sonja Jankov, the city itself is the starting point, and the end is an abstracted rhythm of the buildings or the molding into organic plant shapes of monuments or towers, which renews and idealizes but at the same time removes the buildings from the historical and the particular. The communist architectural landscape of Bucharest can be seen as one huge archive on display, which inevitably ends up defining a group of people (for those outside the community). This is of course part of the stakes of a residential project in a foreign country. Even the prehistoric past, seen in Nicole Hewitt’s exhibit, through copies of Neolithic statuettes of different cultures that lived roughly within Romania’s contemporary boundaries, is a means of constructing an identity, be it national (how these cultures are integrated into Romanian national history), gender or spiritual (the so-called Goddess movement) or even extraterrestrial (how some see these statuettes as representations of promethean alien visitors). Hewitt invites us to detach ourselves from what we know and try to imagine having to piece together the stories of an age from disparate archaeological findings, which can just as well be a statuette as a magazine cover. The iconography of optimism and of ultimate human triumph in face of inhuman threats tell of a narrative we no longer identify with, whose significance has become abstract and theoretical, its signs and symbols on the same path of estrangement at the end of which lies significance the Neolithic figurines.

The cohesive force of the historicist vision (and, implicitly, of that of the exhibition at hand) does not stem from the fight for a potential and desirable future, but through identifying with a common (national) past, profoundly mythicized and fetishized, following a tendency in contemporary art of looking toward the past, an exercise of introspection much as the introspection of the self emerges when the explorable surrounding world is exhausted. The contemporary predominance of dystopian fiction (in contrast to the today recessive optimistic, world-building fictions of the past), while hard to weigh statistically, is an idea easy to encounter in the public discourse, and its causes have been linked to what has come to be called a historical turn (Mark Godfrey, The Artist as Historian) in contemporary art, though these are hard to pin down and delineate, likely combining a general distrust in utopia-creating imagination as part of a perceived postmodern teleological crisis with the pessimism of a population traumatized by contemporary calamities and disappointments (we could perhaps call them catastrophes) (Dieter Roelstraete gives as an example the failure of the large-scale protests against the invasion or Iraq) and by the permanent threat of massive natural disasters brought about by manmade climate change and environmental destruction, all of whose effects are only amplified by mass communication channels, which make them practically inescapable.

In this case study on a corner of Eastern Europe, after a socialist realism which brought into the present and painted on top of it the new, emerging yet already there, communist world of prosperity, seen by theoreticians of the time as naturally still unstable, being part of a yet-unfinished dialectical process, as noted by Boris Groys, proposing another optimistic future takes second place until an interrogation of a local and global historiography of fabricating the future is realized.

“The Undisciplined Eye. Everyday Life Beyond Narration” was at CEREFREA Villa Noël between the 1st and the 10th of September 2016.

POSTED BY

Rareș Grozea

Rareș Grozea (born 1995) got his B.A. in Art History from the University of Bucharest and is currently studying for a Master's in Berlin....

Comments are closed here.