Many cities around the world, especially the big metropolises with tumultuous histories, have local legends about hidden tunnels running underneath the streets. Bucharest is no exception. Dating back hundreds of years ago, when the land was riddled with noblemen’s estates with sprawling vineyards, many wealthy properties were endowed with huge cellars inside which were stored dozens, even hundreds of barrels and bottles of wine. The cellars of the richest boyars would often be extended into long tunnels which served as escape exits during times of civil unrest and war. They were so spacious that an entire wagon could easily pass through.

The powerful men of Romanian politics were no strangers to escape plots. Communist dictator Ceaușeascu is infamous for his megalomaniac vision when he ordered the erection of the House of Parliament. It was not only meant to be grandiose and opulent, but also safe. Underneath it lies an anti atomic bunker and underground tunnels with several exit routes. Dubbed Ceaușeascu’s personal subway line, urban legends describe these tunnels as stretching for miles and miles, leading up to several key locations throughout the city: The Central Committee, The Ministry of Defense, Victoriei Square and even the airport. It’s almost as if the late dictator foresaw the social upheaval that would be his downfall and prepped for it, but in a strange twist of faith, his unsuccessful escape attempt was ironically by flight.

Some of these tunnels undoubtedly exist and can even be visited under special circumstances (see the designated Top Gear episode), most of them, however, are closed off by the Romanian Secret Service, which only enriches the urban folklore surrounding them. All of these stories captured the imagination of choreographer Krassen Krastev, the second international artist to take part in Live Action Cell, Ioana Păun’s brainchild – an artist residency supported by the National Museum of Contemporary Art that reunites international artists and local anthropologists in an urban-artistic research, presented to the public as a performance art piece.

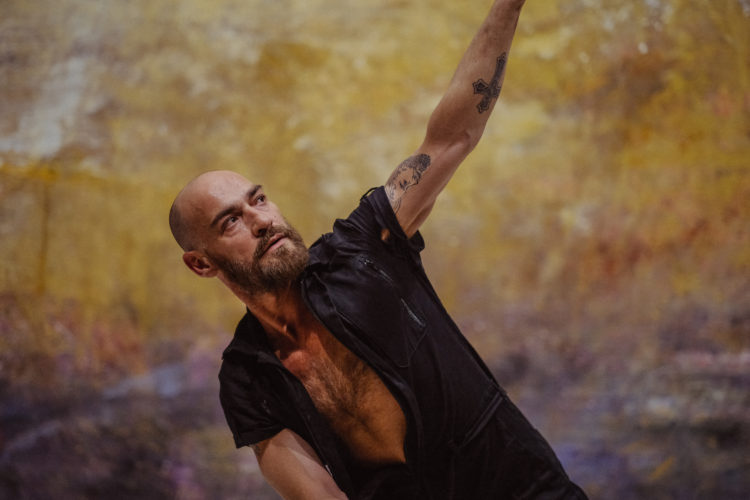

Krastev is an artist of Bulgarian origins who has been living and working in Lausanne, Switzerland for the past twenty-five years. He dabbles in dance, performance art and acting with gender and sexuality as his main topics of interest. His approach to his craft is highly personal and intuitive, not to mention hybrid, always activating at the intersection between the black box and the white cube. Of course, this made him the perfect contender to engage in the synesthetic practices proposed by curator Ioana Păun with Live Action Cell. Teamed up with anthropologist Andra Popescu and performer Ionuț Arnăutu, Krassen Krastev soon realized that this is encounter might have been destined to take place.

In recent years, performance art witnessed a veritable renaissance in the wake of major paradigm shifts. As postmodernism takes its last breath, metamodernism, or the new sincerity movement is slowly but surely establishing itself as the new dominant “ism” in contemporary art. Leaving aside the cold, informal, deconstructive practices of its predecessor, metamodernism turns its back on cynicism and embraces empathy and solidarity as a means of artistic expression. And performance art’s versatile, ephemeral, adaptable, hard to pin down nature goes hand in hand with these concepts. We’re no longer talking about art that simply is, but of art that happens before our eyes, a kind of art that is not simply seen, but experienced. Today’s most engaging performance pieces rely on the public’s sensibilities and perception, rendering art statements virtually useless, thus giving birth to new, novel and personal models for receiving it.

A key aspect of metamodern endeavors is collaboration and process, which are just as important as the finite art piece itself. The art of new sincerity is not an object, but an encounter, a coming together of many minds and visions that is not limited to only one reading. Rather, the meaning and/or conclusion is often left open-ended, leaving room for the mind to wonder. In this sense, the research for such a work of art takes place outward as well as inward.

With all this in mind, revealing the process of artists engaging with metamodern practices makes it that much more interesting, and in the case of Tun.el, we discover that synchronicities of all manner abound. Krassen Krastev is familiar with the local art scene and histories, having collaborated in the past with various performers from Romania’s queer community. His performances make use of dance, costumes, music in a theatrical fashion with which he brings to life various personal affects through queer aesthetics. Their hybrid character means that Krastev frequently takes his craft in all sorts of venues, adapting it to its ever-changing context. His art demands he always keeps an open mind and spirit to his surroundings and the people he comes in contact with, key characteristics for any metamodern artist. As he arrived at the House of Parliament, Krastev undoubtedly sensed the immense historical, social, but especially emotional baggage that laid before him – opulence and oppression, power and constraint, isolation and safety, dichotomies he has dealt with before.

Anthropologist Andra Popescu provides the historical context of the premise, offering important clues that align to the artist’s own interests. Having laid out the social background of Tun.el: the facts regarding Ceaușescu’s failed flee, speculative maps of the tunnel routes and internal political affairs know-how, it was time to ask the real questions. Wherein does the endless fascination with the mysterious tunnels lie? Is it the tragic faith of their makers, the physical and emotional labor that went into their construction? Is it the anguish, claustrophobia and despair that haunt these subterranean lairs? If only these tunnels could speak.

The collaborative work of Krastev, Popescu and Arnăutu was an organic process in more ways than one. Above everything, the production of Tun.el heavily relied on personal human interactions, more so than skills and professional backgrounds; it was important for them to be on the same page and act together as one. And funnily enough, as the three got to know each other, they realized the synchronicities that that tie their fates to the tunnels: Ionuț shares his birthday with Elena Ceaușescu, while Andra shares hers with Nicolae himself and Krassen is born on the same date as Andra’s mother. The articulation of this bloodline led the group to consider the literal tunnel system as a living organism that they could bring to life through performance. In this sense, it could easily be said that Krastev is the tunnel’s body, Andra is the mind and Ionuț comes in the to give voice to the silent catacombs.

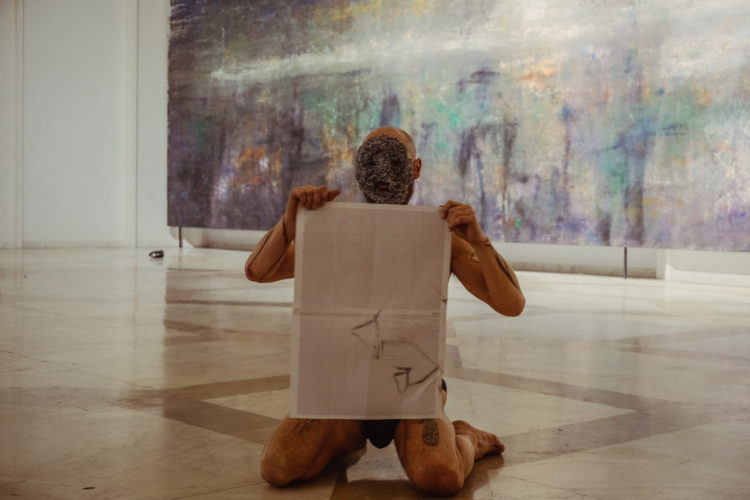

The specific location for Tun.el, the museum’s decadent marble room provided even more favorable coincidences that came to complete the overall feel of the piece. Its ringing echo and dim lights gave the impression that you were underground. The tilled patterns on the floor resembled an intricate map of routes leading nowhere, which Krastev decided to incorporate into his choreography. Make no mistake, although improvisation plays a crucial part in the trajectory of a performance, each of the actions therein have a distinct purpose and were rehearsed beforehand.

I consider it to be a huge privilege to be able to witness the making of a work of art. Watching the group practice days before the performance, when they were still figuring out its components was a real eye opener in terms of how a metamodern performance piece, which often resembles and heavily relies on improvisation and feeling the crowd, has nothing to do with improvisation, not in the literal sense anyway. Tun.el is constructed as contemporary dance piece meant to evoke certain tableaus related to various connotations of the Bucharest underground tunnels through an affective filter. Krastev, the embodiment of the tunnels, goes through a series of motions that depict the state of mind that might have reigned over the many soles who passed through these walls: hope at the thought of escape, following a predetermined route, pouring over endless speculative maps that lead to nowhere, the missed heartbeats at the mysterious sounds echoing from unknown sources, despair, adrenaline rush, the lack of air, the ripping of one’s clothes from one’s body, ultimately losing one’s self.

This separation from the self is made visible with performer Ionuț Arnăutu, who sits in one corner of the room and plays the role of the tunnel’s voice. Using a mic that echoes his voice to infinity within the pristine marble room, Arnăutu speaks in the name of the body, but is separated from it. His mumbled words mirror Krastev’s actions and describe the darkness and the monsters lurking within, the impossibility of escape, the many workers and soldiers who dug the tunnels, while growing ever so distant from its body counterpart. At times, the two performers meet in an entanglement of force and communion, the body tries to overpower the voice (in its head) through compassion. Together, they evoke a certain atmosphere, a certain feel and herein lies the essence of this performance piece. Arnăutu also plays the role of sound effects producer, using various objects to make the eerie noises that haunt Krastev: metal bottle caps spilling onto the marble floor, a plastic bottle which is later used by Krastev for twisting and turning. The final encounter between body and voice takes place in a glass aquarium that graces the center of the room. This unsettling prop acquires various meanings throughout the performance: it is a fragile pedestal that temporarily sustains the hero’s hope, it is a false safe space that exposes rather than shields, it is a transparent coffin that suffocates.

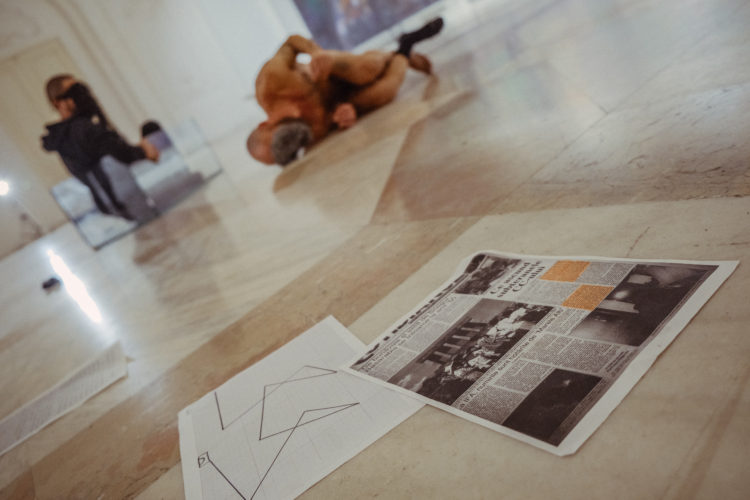

The group rehearsed this scenario every day for a week. Krastev and Arnăutu would perform, each time bringing new components and dropping others in the process. Andra Popescu would watch from the side, film the rehearsal and take notes. Then, the trio would retreat somewhere quiet and discuss: what worked, what went wrong, what can be improved, what new connections could be glimpsed in between Krassen’s moves and Arnăutu’s words? With her background in visual arts, Popescu offers some valuable insight from the perspective of the viewer. She pertinently addresses any aspects that might seem vague or misleading, offering tips on how to improve them. Popescu did not just fulfil her duties as an anthropologist, conducting the historical research that constituted the basis of Tun.el, she also actively contributed to the artistic process as well and helped make the one factual reference to Ceaușescu’s tunnel system: the maps and papers that Krastev frenetically consults, later scattering them at the audience’s feet are possible routes, newspaper clippings and official documents.

It was this coming together, this mutual understanding, respect and care for each other that is worth noting in the creation process. This encounter should be highlighted just as much as the performance piece itself because it creates a frame for openness and empathy, the tools of trade for metamodern art that have the power to generate non-linear narratives. In this sense, in the many rehearsals and encounters that took place leading up to the public showing of Tun.el, Krastev, Popescu and Arnăutu have each brought their own affective contribution to the definitive piece. For the final performance, they were also accompanied by local Bucharest selector Bogdan Scoromide who provided the subterranean soundscape that ties the work together and creates an atmosphere heavy with foreboding. That evening, Krastev’s body acted as vessel for all the spirits inhabiting the tunnels with Arnăutu speaking on their behalf, all amid the crowd. There was no boundary between audience and public, people were free to move around as the artist went through the motions and hastily passed them by. The performance became an intimate study in movement, gesture and action without losing its critical edge. The final and most powerful image of Tun.el cleverly and thoughtfully incorporated the collective contribution of all members – Krastev’s body as a canvas, Arnăutu’s action and one of the papers provided by Popescu – into a simple yet effective gesture: during their final encounter in the aquarium, Arnăutu draws a map on Krastev’s back, which he then transfers it onto a paper by laying on it. In the end, he takes the paper and triumphantly shows it to the audience, revealing a new map created through the combined efforts of body, voice and mind. Whether this collaborative moment was intentionally conceived as such or it naturally occurred out of the emotional work of the team remains unknown, but it stands as a testimony to the many links and connections that can happen deliberately or otherwise within metamodern practices.

Tun.el has proved to be yet another successful example of metamodern performance art, the kind that poses questions of social, aesthetic and affective nature, demanding for a thoughtful and sensitive reading. This was part II of a series of editorial pieces on Live Action Cell. Read part I and III.

POSTED BY

Marina Oprea

Marina Oprea (b.1989) lives and works in Bucharest and is the current editor of the online edition of Revista ARTA. She graduated The National University of Fine Arts in Bucharest, with a background i...

marinaoprea.com

Comments are closed here.