Floriama Cândea explores the dynamics between objects and how we perceive them by creating hybrid visual identities. Her versatile toolkit includes interactive, kinetic, and video installations, sculpture, experimental electronic objects, drawing, and print, with an additional focus on creating images using biomaterials. With the complex relationship between science, philosophy, and technology at the center of her artistic practice, she questions our role and the stakes of the Anthropocene at the dawn of a possible new era. Through her installations, she questions beliefs and patterns and encourages us to reevaluate the mental constructs that shape our understanding of the present and, implicitly, the future. In this way, Floriamea’s works activate the imagination and function as gateways to alternative narratives and scenarios. She is the co-founder of Qolony, a cultural association in Bucharest dedicated to building bridges between various disciplines and communities of professionals. These include contemporary artists, scientific researchers, and various technologists, united by a passion for interdisciplinary practices and their creative results.

You were trained as a multimedia artist, but science has come to occupy an important place in your work. How did you get from art to science?

I don’t think I went from art to science. I haven’t left art, but my interest in science probably stems from the philosophy of science—as an additional lens through which I view the world and ideas. My journey from painting to art&science was not planned or programmatic, but rather a natural evolution of curiosity and the need to understand the phenomena around me more deeply. Ever since my time studying painting at the National University of Arts, I have been preoccupied with translating natural and sensory processes into images. The transition to interdisciplinary art was fuelled by a fascination with what is not immediately visible—the invisible mechanisms of the world, from data flows to microecologies. Collaborations with researchers in the exact sciences and biology have opened up and sustained these perspectives, allowing me to build a diverse practice in which continuous learning keeps me very enthusiastic.

What else motivates you in your work as an interdisciplinary artist, besides continuous learning?

Working with multiple media and disciplines gives me the freedom to interrogate reality from different angles. I am motivated by the idea of creating contexts in which technology is not just a tool, but a partner in critical reflection. But most of all, I am motivated by the fact that I am always learning new things, hearing different perspectives, and constantly setting myself new challenges. Interdisciplinarity is not just an aesthetic strategy, but a way of building an active relationship between knowledge, environment, and form.

What is the medium of expression in which you feel most comfortable?

I would be tempted to say drawing—it seems like everything starts there, even if it doesn’t always show in my work. I don’t really show my drawings; I don’t think I have a clear favorite medium. I like to experiment and test media that are less familiar to me, if I feel they are suitable for the idea I want to express. I often find myself learning from tutorials, because I don’t know exactly how to make what I imagine visible — and that’s part of the process. I wouldn’t say I like instability, but I’m fascinated by how an idea transforms when you explore it through other media. I feel comfortable with interactive installations that involve movement, biological or technological feedback, even though I know they can be complicated to produce and maintain. At the same time, I am attracted to slow processes, such as those in bioart. My works often combine drawing, sculptural objects, and electronic components, and this hybridity gives me a generous space to experiment.

What role does the object and its visual identity play in your work?

I am interested in the idea that the identity of objects is not fixed, but depends on how we perceive, understand, and classify them. I have always been intrigued by the way we assign identity to completely new, unknown objects. Encountering such objects is a creative act in itself for me—based on our knowledge and experiences, we generate speculations, even fictions, constructing new taxonomies that map out territories of desire and possibility. Between reality, fiction, scientific truth, and speculation, the boundaries often become difficult to define. Information circulates between fields and always leaves room for imagination. Nature—with its integrated rules, which we usually know through science and mediated technologies—always has an advantage over our efforts to decipher it.

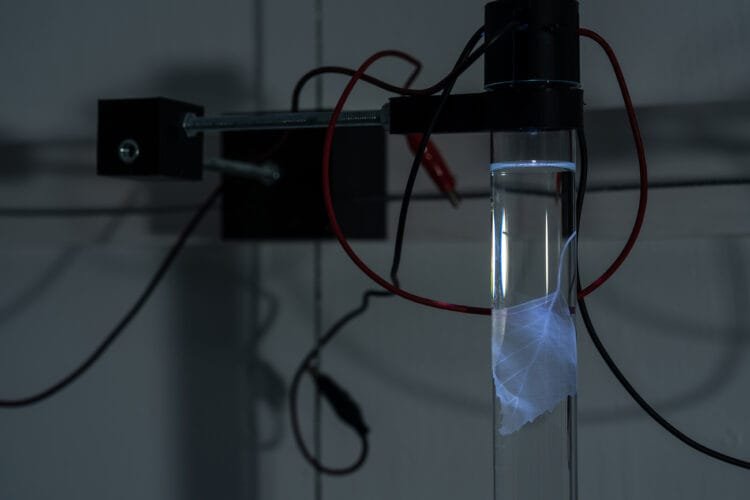

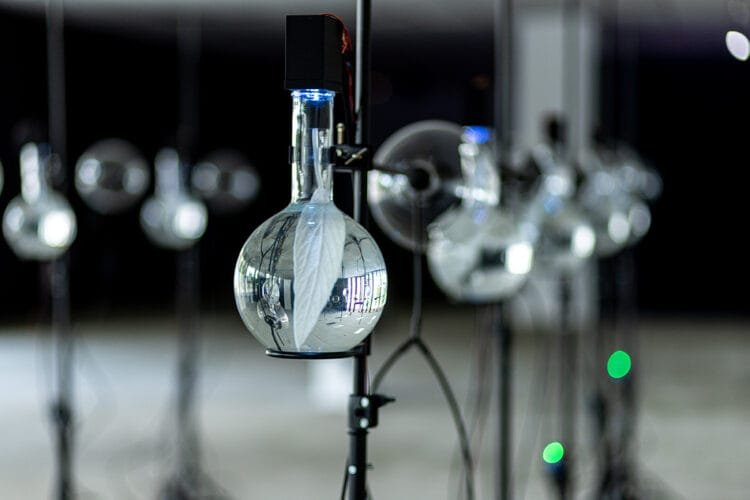

For me, the object is a carrier of memory, not just an aesthetic form. I am interested in how an object can suggest an invisible process or a broader ecology. The aesthetics of my work often derive from scientific research tools, but I try to recalibrate them poetically.

How did you manage to tame the antinomies between reality and fiction, natural and artificial?

I think that rather than “taming” them, I prefer to let them coexist in a productive tension. My works do not offer definitive answers, but create frameworks for reflection in which these oppositions can be reconfigured. For example, I use living organisms in technological installations precisely to question the boundaries between control and chance, life and simulation.

What is the unifying movement between aesthetics, science, and philosophy in your practice?

Probably the question. Each work begins with a question that troubles me and that, most of the time, has its roots in all these dimensions: What does breathing as a common gesture mean in the Anthropocene? What is perception in a non-human system? What does a living object mean? Philosophy, science, and aesthetics provide me with the vocabulary and tools to formulate tentative answers.

How do you convert scientific concepts or processes into art?

My work process often starts with the desire to understand a scientific phenomenon—sometimes through direct collaboration with specialists, other times through personal exploration, driven by a curiosity that combines an interest in certain concepts with the need to give shape to an idea. It is not a matter of faithfully transposing science, but rather a process of simplification and reimagining, in which a scientific concept can become a poetic gesture, a flow of data transformed into a luminous pulse. Other times, it all starts with many questions and technical uncertainties—and deciphering them becomes a process in which collaboration with specialists becomes essential to bring coherence and depth to an intuition or a state that I want to convey.

What role does dialogue play in your work?

It is a central element. None of my recent projects were born in isolation. Dialogue with researchers, artists, communities, or even visitors to the installations generates multiple meanings. These conversations become part of the work—they leave traces, open up new questions, and chart unexpected directions.

Are there any events or figures from your childhood that shaped your path toward your current practice?

I grew up in an environment where experimentation was a form of play. Together with my brother, we built all kinds of improvised systems—circuits, maps; we liked to take things apart, rebuild them, explore fun physics books. I clearly remember my fascination with detail and the hidden mechanisms of things. This childlike curiosity is still present in my practice, only now it has become more structured and contextualized.

Where does your passion for biological phenomena come from?

From a need to understand the intimacy of the living world, beyond metaphor. Biology provides me with a framework to explore not only the aesthetics but also the ethics of the relationship between humans and nature. I like working with slow processes, such as cell cultivation or the growth of biomaterials, perhaps because they involve patience, care, and a form of co-creation. I like the idea that there are built-in rules in the natural world that you don’t know in advance—and even when you do know them, you can’t reproduce or control them completely. Nature always finds ways to surprise us.

How do you reconcile nature with technology?

I try not to view them as opposites and choose technologies that are as non-polluting as possible, or at least recycle older technologies. In my practice, technology becomes an extension of perception—an intermediary, sometimes even an ally of nature. I try to develop soft, cooperative, unstable technologies that allow themselves to be influenced by the environment and do not try to dominate it.

How do you relate to posthumanism and transhumanism?

I find myself more in line with the critical directions of posthumanism—those that challenge the centrality of humans and propose a multi-species thinking based on coexistence and interdependence. I am not interested in transhumanism in its techno-optimistic form, oriented towards overcoming the human condition through technology. I am more concerned with how we can live together with non-human alterities, how we can rebuild our relationships with the environment and with others—human or not—in a more equitable and empathetic way.

How do you cultivate patience and consistency?

Through deliberate slowing down. I try to cultivate slow rhythms not only in my work, but also in my daily life. Practices such as handwriting, drawing, or careful documentation become ways in which I keep consistency alive and create an inner space where thoughts can ferment.

We met at the SIMULTAN Festival in Timişoara, which celebrates its 20th anniversary this fall. How did you perceive the festival at first glance?

For me, the SIMULTAN Festival was one of the first platforms in Romania that created a real space for dialogue between art, sound, technology, and critical thinking. During my formative years, it seemed to me to be one of the most courageous and challenging cultural phenomena on the local scene. I applied many times to their calls for proposals and, from the first time I participated, I perceived it as an experimental and free environment. In the meantime, it has become a landmark and a community that I feel part of.

The theme of the SIMULTAN 2025 festival is Re-Mediate. What is your take on the concept of re-mediation?

This year’s theme of the SIMULTAN festival—RE-MEDIATE—is, of course, dense with connotations, and I resonate with several of them. On the one hand, I am interested in the idea of transforming, reinterpreting, or reconfiguring one medium through another (in line with the theory of re-mediation). On the other hand, I also find the meaning of “remediation” as a form of repair, adjustment, or improvement relevant—scenarios that may be fragile but necessary in order to imagine more sustainable futures.

For me, re-mediation is an artistic and ethical gesture of translation and recontextualization. In my practice, it does not only mean transposing content from one medium to another, but especially putting signals—material, affective, or ecological—back into circulation. I am concerned with how technologies (including unstable or speculative ones) can function as sensitive interfaces that render invisible processes visible: breathing, photosynthesis, heartbeat, networks of species coexistence.

I frequently work with translations between science, technology, and poetry, but also between living systems and technical systems. In this sense, re-mediation becomes a practice of activating and reframing perception—a circuit in which data, matter, and emotion can be recharged with new, local, and/or contextual meanings.

What projects are you currently working on?

I am currently in the research phase of the Coding Drops project, which will also be exhibited at the SIMULTAN Festival this fall. Together with researcher Marian Zamfirescu and programmer Cristian Balaș, I am working on the development of an optotronic network inspired by biological perceptrons—an experimental system that aims to rank photosynthetic species according to their efficiency in CO₂ conversion. This is a direction that has been on my mind for some time, part of a broader conceptual approach to viewing the atmosphere as a collective process, consisting of interactions between species, technologies, and breath flows. The production stage of the project will take place during a residency in Vienna.

At the same time, I am preparing for a residency in Greece, as part of the European project Transition to 8, where I will continue the research I began in The Somatist, The Entropist and the Skeptic, focusing on forms of coexistence between species, in technology and nature.

How do you see SIMULTAN in 20 years?

I like to imagine it becoming a transnational platform for artistic research and production, hybridized with forms of critical education, mobile laboratories, sensory archives, and the like. What I mean is that I see it as an infrastructure that could remain relevant for many years to come because it has always kept up with the times. I don’t know what “relevant” will mean in 20 years, but I have a feeling that SIMULTAN will always remain fresh.

POSTED BY

Maria-Luiza Alecsandru

Maria-Luiza Alecsandru is a cultural journalist through training, curator and cultural mediator through adaptation, author and artist through passion. She works with video, installations, photography...

Comments are closed here.