In her novel Hunden (1986), Kerstin Ekman, an unexpected voice within the posthumanist discourse, follows the journey of a dog lost in the winter landscape of a Swedish forest. Ekman’s acutely visceral descriptions capture the experience of the wild and the inevitable return among humans. The domesticated animal cannot immerse themselves in the affective space of the forest, as their experience is conditioned by the role played within the community of the Anthropocene. In the end the dog is found.

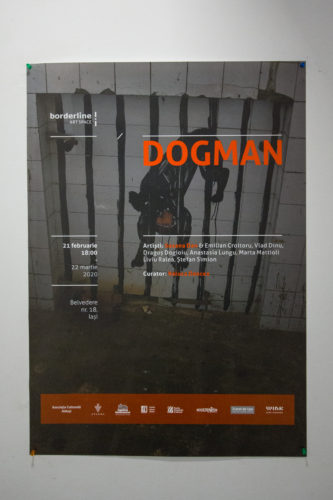

This theme of finding the lost is also at the core of DogMan, an exhibition opened in February at Borderline Art Space, extended till July because of the pandemic, and ended on the other side of recent history. In the space of the Iași-based gallery, a group of artists comprising Suzana Dan & Emilian Croitoru, Vlad Dinu, Dragoș Dogioiu, Anastasia Lungu, Marta Mattioli, Liviu Ralea, and Ștefan Simion evoked a different affective landscape of canine experience. In line with this theme, an extensive corpus of works by Suzana Dan, mostly paintings made after 2001, was accompanied by multimedia interventions from the group of young artists. Yet their point of intersection is not Belvedere street in Iași, but a rediscovered place.

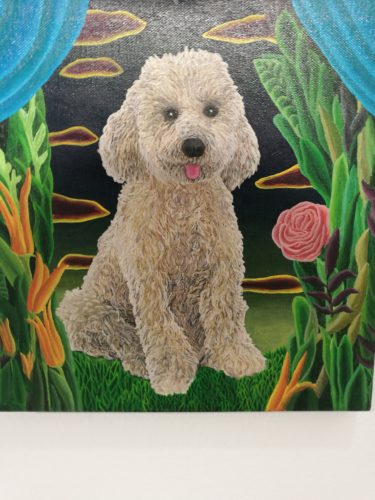

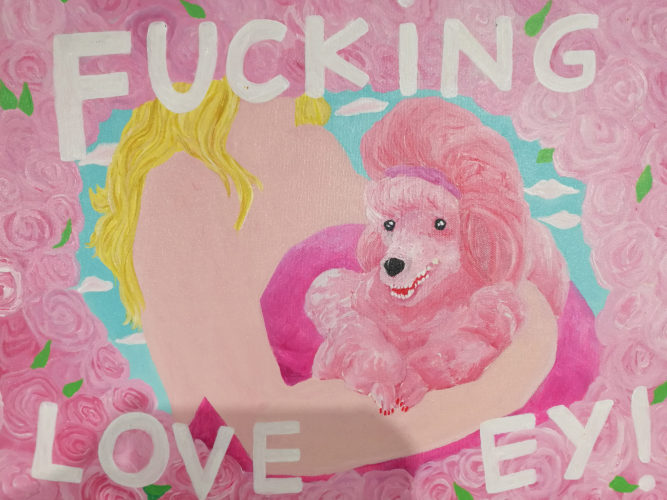

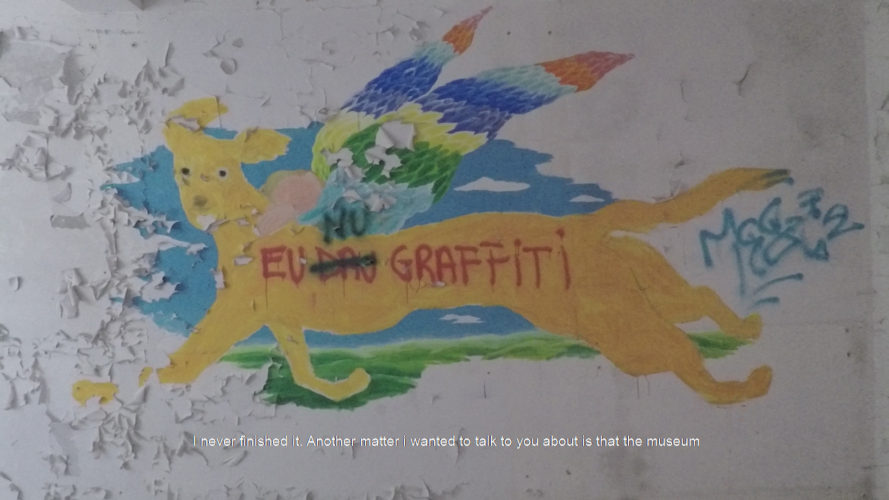

In the summer of 2019, a group of students was traveling through Sinaia in search of material to film. The task they received from Raluca Oancea and Simona Popescu at the creative retreat they were attending brought the young artists before an abandoned building, in which they would come face to face with a pack of dogs. The canine characters, which made up a large graffiti mural, ran the representational gamut from grotesque to candid. Some rooms displayed contorted, hanged, or anguished creatures in cages, while others housed affectionate dog portraits framed cameo-like with the name written above. In some rooms, twisted bodies lay splayed on the grimy walls, their viscera extending through the exposed metal pipes. Other rooms seemed tributes to loyal companions. The images were often accompanied by text, like “All dogs are predators” or “Fucking love, ey?” With room after room, a whole gallery of canine existence came to be, marked by the diversity of human control and/or love.

Only when they returned to Bucharest did Raluca Oancea’s students find out they had re-discovered Museum of Dog, Suzana Dan’s in situ installation made during 2007 as part of the ArtistNe(s)t residency. Afterwards, Raluca Oancea, this time as the curator, would launch a series of exhibitions in which the young artist would be given the chance to collaborate with the more experienced Suzana. DogMan is the last in this series.

Inspired by how Suzana’s fresco in the abandoned restaurant building in Sinaia portrays to the condition of what she describes as “the most human of animals,” the young artists would come up with their own multimedia ideas. Suzana’s paintings and texts, remarkable both through their sharp humor and their honesty, showing a sincere love towards dogs, would be the starting point for a series of animations and interview-type videos, with both realist and experimental approaches. The general idea of the exhibition revolves around the posthumanist theoretical program and the notion of catharsis. In a Facebook post, Suzana mentions this cathartic effect she reached producing and doing research for the Museum of Dog, which commemorates a canine friend’s passing and condemns the cruelty faced by these creatures whose very existence is conditioned by human tolerance.

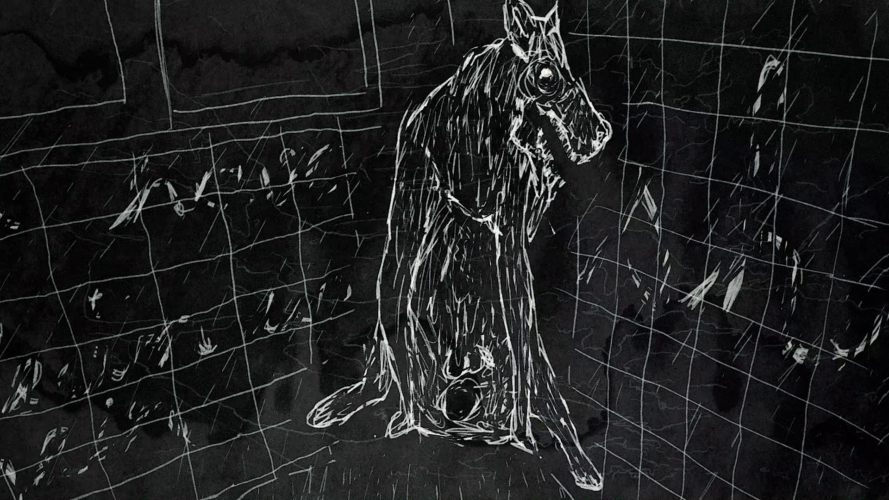

Situated in the liminal space in which nature breaks down and reassembles itself as “civilization,” the existence of the dog becomes contingent upon human tolerance. Oftentimes the value of a dog in society, the thing that differentiates a mutt from “man’s best friend,” lies in their obedience towards humans. Also, oftentimes, man’s best friend is not spared the trauma inherent in the purely performative function they fulfill. This reality is reflected both in the horrid silhouettes of the tortured creatures painted in the basement of the abandoned restaurant as well as in the young artists’ contributions, who were for the most part inspired by the macabre atmosphere. The sound material, punctuated by glitches, works together with the animations that offer one last breath of life to those tormented bodies or carry the word “fleas” along the decrepit walls. The “parasite,” this omnipresent word in the cultural discourse of early 2020, describes a certain relationship between humans and dogs, encompassing both the element of intimacy as well as that of toxic dependence, of consumption.

Overall, the students’ interventions evoke the oppressive, dreary, fragmented atmosphere of the spontaneous encounter with the Museum, from which they extract, physically, visually, or acoustically, a canine skull, a few shards, or pieces of plaster. These elements, together with the erasure of a drawing (back then still anonymous), outline an artistic experience of ephemerality and degradation.

After the author of the murals was revealed, a final visit to Sinaia was documented by Vlad Dinu, Marta Mattioli, and Dragoș Dogioiu in a video material, where the voice of Suzana Dan (re)introduces Museum of Dog in the context of its initial intentions. The space is explored through a fisheye lens, a circular perspective allowing us to imagine the careful, vigilant return to a rediscovered place. The video in question is displayed at Borderline together with a window taken from the building which frames a QR code leading to a dedicated website and a series of semi-transparent canvases printed by Suzana with some of the Museum’s characters.

At this point we can go beyond the aesthetic qualities of the works and remark on the project’s fulfillment as a collaborative act. The harmony between temporal layers, between reality and representation, between painting, installation (I would mention here Suzi’s bestiary, Suzana’s painting accompanied by the famous couch decorated with gold leaf and red hearts), and moving image (video, glitch, 3D animation), all blend in with a certain disappearance of the author. This withdrawal, typical of a postmodernist and posthumanist project, potentializes both Suzana Dan’s paintings with their vivid colors, playful campiness, affection, and sharp humor, as well as the audio and video works made by the young artists. Together they recreate an affective topography of the space and generate an opposite critique for the Anthropocene.

The exhibition DogMan, curated by Raluca Oancea, took place at Borderline Art Space starting with February 21st 2020, it was interrupted by the pandemic and reopened during the summer, until July 9th 2020.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Sandra Ungureanu

Sandra Ungureanu (b. 1997) studied ceramics and textile art at the National University of Art in Bucharest. She is interested in the intersection between ethnography studies and artistic practices, as...

Comments are closed here.