Before I begin to properly recount what there is to see at UNAgaleria during December 11th 2014 – January 31st 2015 as part of the exhibition Another air. Jan Švankmajer & The Group of Czech and Slovakian Surrealists, maybe it wouldn’t hurt to recap a little art history. The artists of this exhibition come from the third or fourth generation of Czechoslovakian surrealists that came together in the late 60s around publications such as Bestiar, Dunganon, Analogon, Le La or Surrealismus, that were secretly published in the country and abroad. The movement began in the late 20s in Prague with the poetism that was promoted by the Devětsil art union, headed by Karel Teige. This was followed by The Surrealist Group of Czechoslovakia, which was active in Prague (Skupina surrealistů v ČSR, between 1934 and 1939), which for a while overlapped with Avant-garde 38 from Slovakia (up until 1948). In Prague, Skupina ČSR continues its activity from 1941 to 1945 with the help of The Surrealist Group of Spořilov (Spořilovští surrealists, named after the neighborhood where they would meet and where most of the members lived) and Group 42, which was later (somewhere between 1946 and 1948) renamed Group Ra. In 1950, art veteran Teige along with other artists such as Istler, Tikal, Effenberger, Hynek and Medek secretly regroup around The Reconstituted Surrealist Group. The soon to be literary theorist Vratislav Effenberger and the photographer Emila Medkova come up with the initiative to reunite the surrealists under The Circle of the Five Objects (1953-1962), at first, and then as USD (1963-1968) with newcomers Roman Erben and Milan Napravnik.

The approximate structure of the group we see at UNAgaleria ended their legal activity in august 1968, when the troops of the Warsaw Pact invaded Czechoslovakia, with the exhibition Princip Slasky (The principle of pleasure) at Narodni Gallery in Prague. From then onwards, the status of the group becomes illegal and stays this way until 1989. Vratislav Effenberger and Emila Medkova were the strongest links of the movement in the early 70s, and not the Švankmajers as it would seem. Back then, Jan was working with Eva on his sixth animated film, Zahrada (The Garden, 1968), under the strong influence of theorist Vratislav Effenberger. He actually made them abandon their previous mannerist style and bring surrealism into their work. They were joined by Karol Baron, Albert Marencin, Frantisek Dryje, Alena Nadvornikova, Jakub Effenberger, Ivo Purs, Josef Janda, Martin Stejskal and Ludvik Svab. Until 1989, the artists showcase their work in all sorts of thrifty spaces, the kind we would call today artist-run or underground, such as Švankmajer or Martin Stejskal’s workshops. But the most intense artistic activity took place in the Samizdat, in almanac publications with confidential circulation or outside the country. The Group of Czechoslovakian Surrealist leave secrecy and make their first public appearance in 1989, with a few changes in the list of members. Vratislav Effenberger had died in 1986, and Jiří Koubek, Andrew Lass (back from the USA) and Milan Napravnik (repatriated from Germany) joined the remaining members. During 1990-1991, the artists take back the name The Group of Czechoslovakian Surrealists, and in 1992 they change the name to The Surrealist Group of Prague, with subsidiaries in Bratislava and Brno.

Back home, the Romanian avant-garde first comes into contact with the Czechoslovakian avant-garde in the late 20s via Contimporanul magazine that promptly reported about the new editorial manifestations from Prague and other cities, highlighting the graphical aesthetics of architecture that most likely began because of architect Marcel Iancu, who was the second editor in chief of the magazine, and Ion Vinea. Articles from Stauba and Disk, ran by Karel Teige, Pasmo from Brno, animated by Artuš Černík, or the long-lived Veraikon are announced, commented, quoted from and sometimes even taken. Our native avant-garde will come in contact with Prague in the late 30s, when Jules Perahim and Grigore Juster, who were in Czechoslovakia at that time, become part of the Avant-garde 38 movement with Ladislav Guderna, who offer the two help with setting up exhibitions in the lobby of Theatre D ’38. The next time the two avant-gardes will meet will take place in Paris: Jules Perahim meets up with Petr Král, and Gellu Naum comes to meet and exchange letters with the co-founder of the Group Ra, the poet and essay writer Ludvik Kundera.

As is well known in Romania, at the end of the 60s and during the early 70s, the poet Gellu Naum is the only member of the Romanian Surrealist Group or Infra-Noir (1945-1948) to remain in Romania and to still believe in the aesthetics of the surrealist avant-garde. He gathers a small group of intellectuals (poets, visual artists, psychoanalysts, literary and cinema critics) and together they go about all sorts of clandestine creative activities up to 1989 and carry on with the same intensity until the poet’s sudden death in 2001. The difference between the Romanians and the Czechs and Slovakians was that the former never had a political or aesthetical program that would follow in the footsteps of the older avant-garde movements. In fact, the only ideology that brought these artists together, either in Comana or Bucharest, was the anti-Ceaușescu movement. It had, of course, a lot of risks that are normally associated with any such semi-institutional opinion with its political implications, but it offered an unobstructed, yet secret freedom to create without boundaries. The only exception of this post surrealist alchemy is the little known yet extraordinary case of Lyggia Naum, the poet’s wife. The Romanian avant-garde, as was with all similar movements, was a boys club, thus historians ignored her and all other wives, nieces, mistresses, cousins and sisters, mentioned only in relation to the artists; but their contribution proves to be nothing less than colossal. Gheorghe Rasovszky, Dan Stanciu, Iulian Tănase and Sasha Vlad are the chronological counterparts of the Czech and Slovakian surrealists, but their being part of this exhibition should be noted, because despite having some tendencies towards post surrealism, neither of them ever had any affiliations with Breton’s agenda.

The Group of Czech and Slovakian Surrealists truly gives another air to the discussions about the historical avant-garde. But the real challenge is whether this other air can impact the contemporary arts. I walked into the National University of Art’s gallery feeling a bit uneasy, preparing myself to witness a perhaps touching parade of artists and pieces that were acting as parasites to their own former glory.

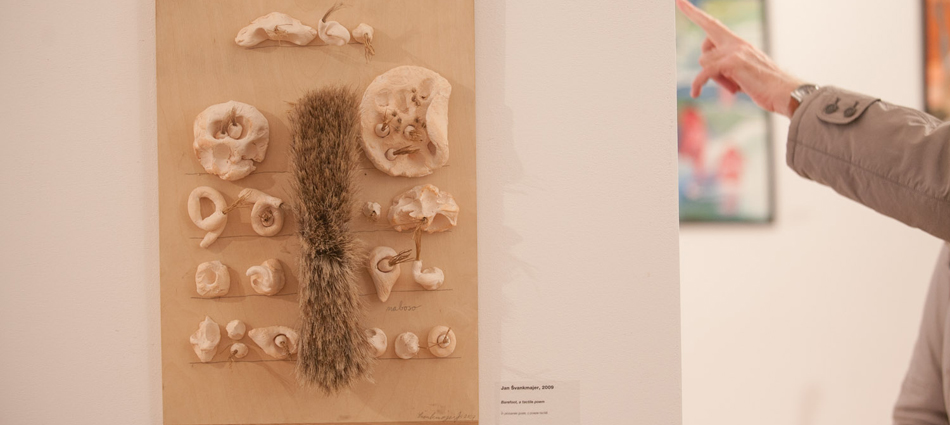

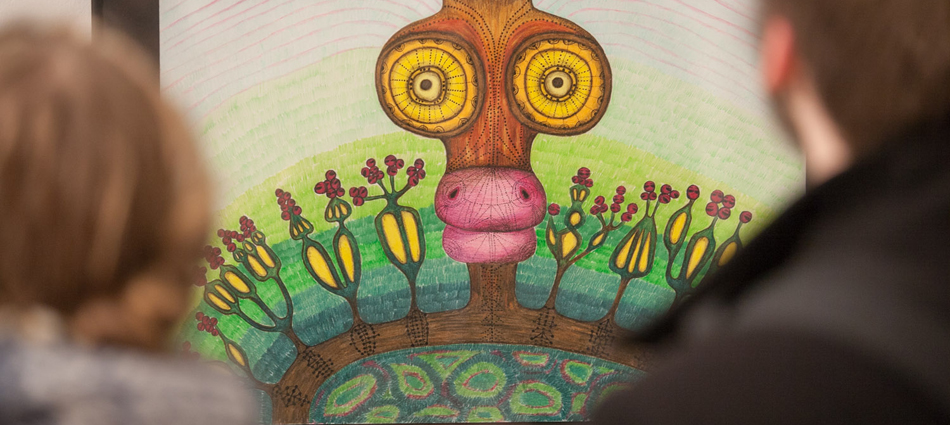

Even though it contains fresh works with a few exceptions – one being Jan Švankmajer’s 1992 animation Jídlo (Food) – the exhibition, curated by Radka Prošková with a little help from artist Bruno Solařík, showcases a vast majority of pieces from after the 2000s. These works have a difficult task in a very heavy historical context. They somehow share the same fate as the metaphorical Angel of History, as it is described by Walter Benjamin, inspired by a Paul Klee painting: they presently march, stepping into the future, but always looking back to the past. One can acknowledge techniques, forms of expression, hints and even themes that are typical of Breton’s own surrealism, but there is no sense of historical stillness because these pieces speak about the present day. Yes, it’s all about l’amour fou and de Sade as they are seen today through the lenses of porno magazines, corporate marketing and pharmaceutical industries; convulsive beauty is what we seek, but the devastating beauty of the ruins of a contemporary civilization is the one that stands out. We can play games and see if we can match the themes to political messages or prospects of memory.

Sasha Vlad and Dan Stanciu’s collages are just as corrosive, with their texts and images overlapping old polytechnic manuals. The dibond remakes of the bilingual volume înainte / după. 52 de apariții trans-vizuale generate de hazard, published by Gheorghe Rasovszky, Dan Stanciu, Iulian Tănase and Sasha Vlad in 2003 by ICARE publishing house, are somewhat careless. Playing with before and after was fun back in its post surrealist time, when hazardously putting together photos, cutouts, illustrations and drawings following the sales patterns of before and after would produce an exciting chronological short-circuit. At one point you could no longer tell if they are hinting at before and after the use of bleach or before and after 1989. My only regret is that I would have liked to have seen some new contemporary works by the two artists – Gheorghe Rasovzky with some post-punk art works, Iulian Tănase with his post-transition poems. It would have made for a better rhyme.

Besides all that, when you go visit this exhibition, you must summarize it and remember it.

Alt aer. Jan Švankmajer & Grupul Suprarealiștilor Cehi și Slovaci, December 11, 2014 – January 31, 2015, UNAgaleria Bucharest. An exhibition organized by the Czech Centre in Bucharest.

Artists: Jan Švankmajer, Eva Švankmajerova, Martin Stejskal, Karol Baron, Jan Daňhel, František Dryje, Jakub Effenberger, Jan Gabriel, Ivan Horáček, Lucie Hrušková, Josef Janda, Jan Kohout, Leonidas Kryvošej, Kateřina Kubíková, Roman Kubík, Andrew Lass, Albert Merenčin, Přemysl Martinec, Radim Němeček, Kateřina Piňosová, Bertrand Schmitt, Bruno Solařík, Ludvík Šváb, Václav Švankmajer, Roman Telerovský, Kristýna Žáčková, Gheorghe Rasovszky, Dan Stanciu, Iulian Tănase, Sasha Vlad. Curatori: Radka Prošková, Bruno Solařík.

POSTED BY

Igor Mocanu

Igor is a PhD researcher in the Art History department of the National University of the Arts Bucharest / UNARTE, with a dissertation titled Political avant-garde. The other face of Romanian avantgard...

igormocanu.wordpress.com

Comments are closed here.