Today, the topic of safety is talked about just as much as the fundamental principle of democracy, freedom. These are haloed terms that we use out of bohemian nostalgia, and sometimes with militant ambitions. Art has adopted these terms with its power to undermine the normal behavioral patterns, to open possibilities for transforming everyday life. But when you follow subversion from a rigid point of view ( as “a whole lifestyle”, as Richard Hoggart, the founder of cultural studies said, or even as “an entire way of conflicting”, as E. P. Thomson responded), there is a risk that this could develop a politically engaged artistic practice of the joking kind, that sustains the general mechanism with self-humor. Artists thus become “clowns of catastrophe”, a phrase that constituted the title of a course that was the foundation for what can be considered a collective response to these kind of positions. The exhibition Safe Perimeter, coordinated by Alina Șerban and Cristina David at Make a Point cultural platform offers in exchange the view of an emotional landscape suspended between the hopes and disappointments of our parents on one hand, and the fears and ambitions of ’90s society, on the other.

When one tries to describe childhood, this perimeter of experience, using the notion of safety, the discussion is overturned by romantic nostalgia. The transnational obsessions for security are constantly using this term. Thus, it seems that we are facing a continuously instrumentalized concept, whose ambiguous meaning is vulnerable even in front of the best of intentions. In order to bring us back to a common ground, I will make a short x-ray on the deviations that the current political discourse brought on our perception of “safety”. I will try and play out the frame in which the term could take back its sensual texture found in 90’s dream pop songs, where suffering and trust are not the currency for love, but the articulating conditions for the neutral space of safety. How can art become subversive for the sensitive perception?

Nowadays, the state promises us everyday peace using institutionalized security solutions as answers to a collective need for protection against an unseen face. Insurance agents have developed legal-technical creations in the olympic networks of the financial market, which allow investors to bet on the occurrence of natural or human cataclysms to secure their winnings; residential complexes are bundled with a dedicated security agency, personal technological devices have incorporated finger-print based password systems and end-to-end encryption for your private conversations. In the movie Existenz (1999), David Cronenberg investigated the idea of a subjective world created artificially using strong flavors of paranoia, where biotechnology becomes the means of reconceptualizing the nature of technology and the way in which it alters our perception on the exterior world. The characters in the film often point out how the game allows them to escape “the most pathetic level of reality” in order to take part in unique experiences. Their adventures, however, are not shown in the film as being unreal, on the contrary – those who are against the game and virtual reality (the realists) are presented as terrorists.

So, the concepts of freedom and safety have become, without our notice, terminological abstractions that are alien to human emotion. Their meanings appear to be determined via the combination of antithesis that is logically articulated by the cultural opposition between east and west. Faced with restrictions and ideals of uniformity experimented by a collective corpus, freedom has a negative meaning as a term that excludes the generally accepted antithesis. We crossed over from collective production to a regime of collective consumption, which provoked in all of us the obsession for the day of tomorrow and artificial wishes for a certain life style.

But despite all of these realities, we all have an unclear memory of a time of pleasure undivided by morality, with no responsibilities and no obligation to always succeed. The displacement of society, a video-performance by Dan Iordache, isolates the rhythm of a jump-rope game – a measure of time when playing outside. 1,2,3 … 1,2,3 … Like a mantra, he begins a ritual: because succeeding and being the most efficient are values imposed by the competitiveness of the teams, exhaustion becomes a subject of artistic appreciation. There is nothing more pure or violent than a child’s pleasure in his game of discovering life. A timeless space unfolds around him, giving birth to the act of seeing as a uninterested perception, separated from the obsession for the finite. A feeling that can’t be communicated, a feeling of letting yourself go in the sensuous world and the simultaneous internalization frees us from the partisan condition (of a certain way of life, ideology, morality) and faces us with a neutral state of pure artistic appreciation. In this dimension, safety can be seen as a condition of man in relation to the real world, where the eye is freed of canons and symbolic organizing. The gaze freed from the burden of memory is amplified, performing its own freedom of re-configuring visual data.

“Safe perimeter” invites us to enter this neutral space, a perimeter marked by a suspended black line that delimits an experiment laboratory, where time and space have new dimensions. In the background you can hear

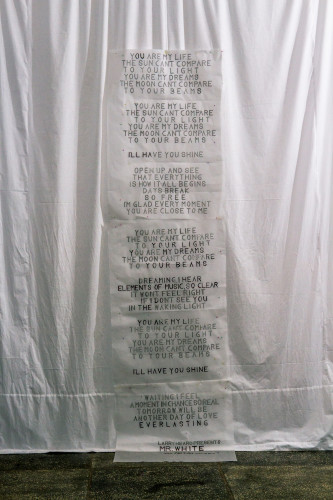

dreaming I hear/ elements of music so clear/ it won’t feel right/ if I don’t see you in the waking light.

After investigating democracy / communism’s ideological binomial that topographically organized the socio-cultural politics, each artists puts forward the reclaiming of sensuous experiences.

Space (Wall 1.0, Vlad-Radu Popescu) and time (Building always means time, Vlad Albu) are transmuted from analytical abstractions in synthetic forms that articulate the convention for an artistic locus. One of the gallery’s walls appears to be broken, recreating the image of the Berlin Wall when it was demolished. On one hand there is the cliché-element of the American propaganda, similar to Michael Jackson’s moonwalk or fragments from G. W. Bush, who was president of the USA at the time, that holds up in Bucharest. On the other hand, the iconoclasm of the soviet regime is played by the visual noise of no network, marked only by division, along with its synonyms. The tension of the two parties’ discourse is being equalized using the television, “the retina of the mind’s eye”. Spacial perception is thereby restored. In a dialectic relationship, time comes in the shape of the rhythm of organic growth, uninterested in the measure of years, periods, or regimes. Building always means time, Vlad Albu’s organic installation, deconstructs history’s basic mechanism – organizing life’s flux in periods and symbolic meanings.

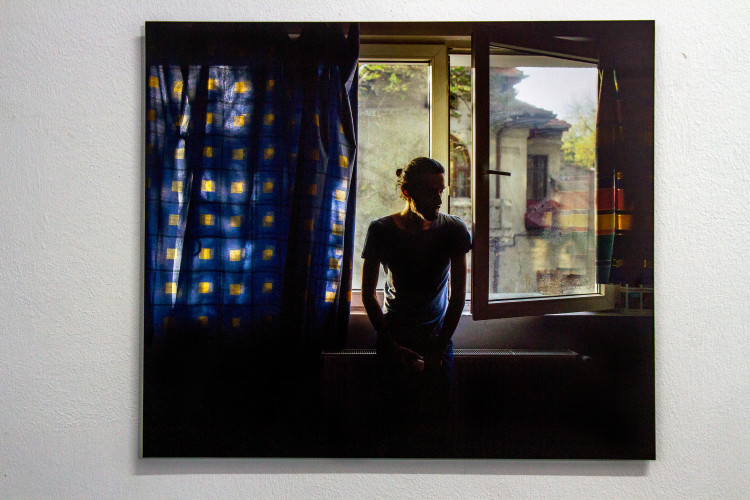

Natural history ’92, City for sale and X PROJECT turn the echo of the falling of the Berlin Wall into text fragments and images that have populated the emotional landscape of personal childhood. Mihai Șovăială and Ana-Maria Preduț de-contextualize them, they blow them out of proportion, they reorganize them in an exercise of personal speculation, thus developing subtle spaces. Natural history ’92 recreates, using two insectarium display cases, the physical and mental space of childhood. The gaze gets a critical distance that allows it to open a space that is counter-fact, where a biological mother regains her independent identity of the little girl she once was. There is no hidden motive behind this intention. “I photograph to find out what something will look like photographed” is something that photographer Garry Winogrand[1] once said to the sentimental amateurs that wanted to patent the photography of human perspective and ignore the camera’s role. We find the same mechanism here, only this time the human eye’s retina takes the role of the machine.

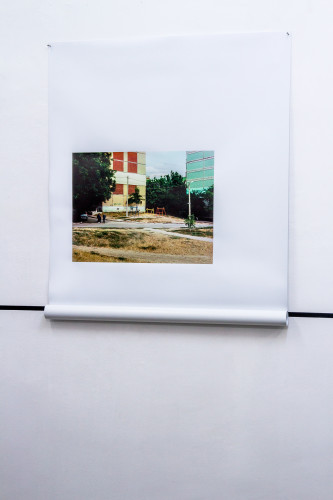

Similar to an algorithm, the gallery space opens up like an arc that unites two different series of photographs: City for sale and X PROJECT. X captures the aesthetic tension between a neighborhood playground surrounded by apartment buildings, with ridiculously distorted jungle-gyms and the careful design of a new vehicle. Nothing changed in the urban geological structure; there are only a few particular elements, just floating like islands, that cause ruptures in the visual linearity of the local landscape. This is the typical case of a “city for sale”, where the aggressive policies of the economy market erase the remaining dreams of urban mega-plans as “complete works of art”. This way, the selection of photos send a discreet message, allowing the possibility of multiple permutations that articulate latent relations that already exist between the photos’ subjects.

I‘ll have you shine

is playing on the speakers. A spotlight is looking for you on the dancefloor. Alla Dicu’s instalation, Dancefloor, articulates the dance space with the intention of suspending, in a tableau vivant, the dance scene between two lovers or two people who met each other over the rhythms of the same song. A space in which the dancers’ past and future becomes cancelled is being rewritten among the bodies’ movements. The dancers’ movements begin to trace a line. After being taken out of context, amateurs or professionals, enthusiasts or drunk euphorics – they all become the subject of an undifferentiated observation for the eye which hunts for pleasure through artistic appreciation.

The iconography elements of western or eastern propaganda, the conceptual mechanisms of the political apparatus, the problematic rigors of the aesthetic taste are taken literally and re-positioned in the frame of playful relationships. Thus, an effect of simultaneous contrast is being generated, in which the constitutive parts regain an extreme dynamic restlessness. The limits in which we find ourselves are no longer coercive. This way the artists investigations articulate a locus in which the content is volatilized. Its way of breaking any law that has bounded generations along a candid temporal suspension of the game’s convention makes it a merciless process. My Bloody Valentines describe this paradoxical duality in the lyrics of the song Soon: I want to Love you/ Yeah, doll of pain,/ I let you get to me. “Safe Perimeter” is, in the end, an exercise that puts forward a study of the mechanisms which shape our perception, while steering clear of puritanical attitudes towards the medium.

[1] Barbara Diamonstein, Visions and Images: American Photographers on Photography, Rizoli, New York, 1982

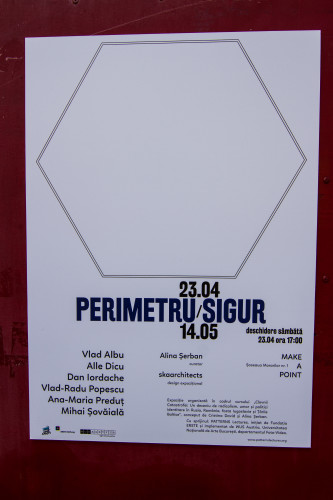

“Safe Perimeter” was at Make a Point between April 23 – May 14 2016.

Artists: Vlad Albu, Alle Dicu, Dan Iordache, Vlad-Radu Popescu, Ana-Maria Preduţ, Mihai Şovăială.

A project coordinated by Cristina David and Alina Șerban.

POSTED BY

Carmen Casiuc

Carmen Casiuc (b. 1994) is an independent art researcher and critic working with ideas and actions that ignite the role of imagination in theoretical science. She studied History and Theory of Art at...

Comments are closed here.