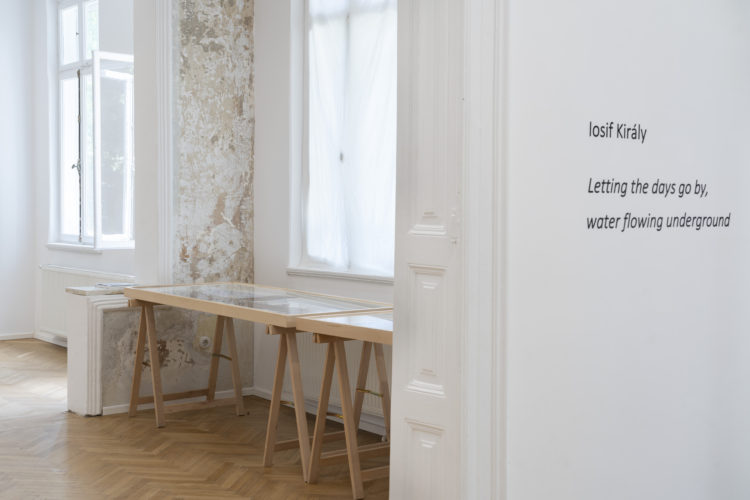

Mid-June, Anca Poterașu and Cristina Stoenescu invited “the art world” to a get-together: the opening of Iosif Kiraly’s exhibition, Letting the days go by, water flowing underground, curated by Cristina. The first opening with sanitary masks, marked by a genuine joy of being together again, in person, which contrasted to the ones “before”, where presence was mostly a social statement of belonging to the world of art.

Undoubtedly, my first curiosity regarded the setting up of the exhibition during the quarantine. I was happy to hear Cristina’s answer: “we had more time to think and rearrange the works”, which stayed in the gallery on Popa Soare during the state of emergency, “amid an abrupt and disquieting silence”. In the context of the fast-forward culture, in which everything happens under the sign of urgency, Cristina’s reply thrilled me. Without any intent to romanticize the isolation, this steady, non-urgent modus-operandi reminded me of the “barrier-gestures against going back to normality” that Latour was contemplating in April[1], launching an invitation to question social automatisms, at a micro & mezzo level. Could we, perhaps, perpetuate this resistance against the culture of emergency, after having experienced the expansion of psychological time during the isolation? Could we maybe save “the emergency” for what concerns threats upon life (be it human and non-human), while taking all the time we need for other activities, so that the result is professional and satisfying?

Let us give it a try. But, until then, I invite you to take a gaze at Iosif Kiraly’s universe.

–

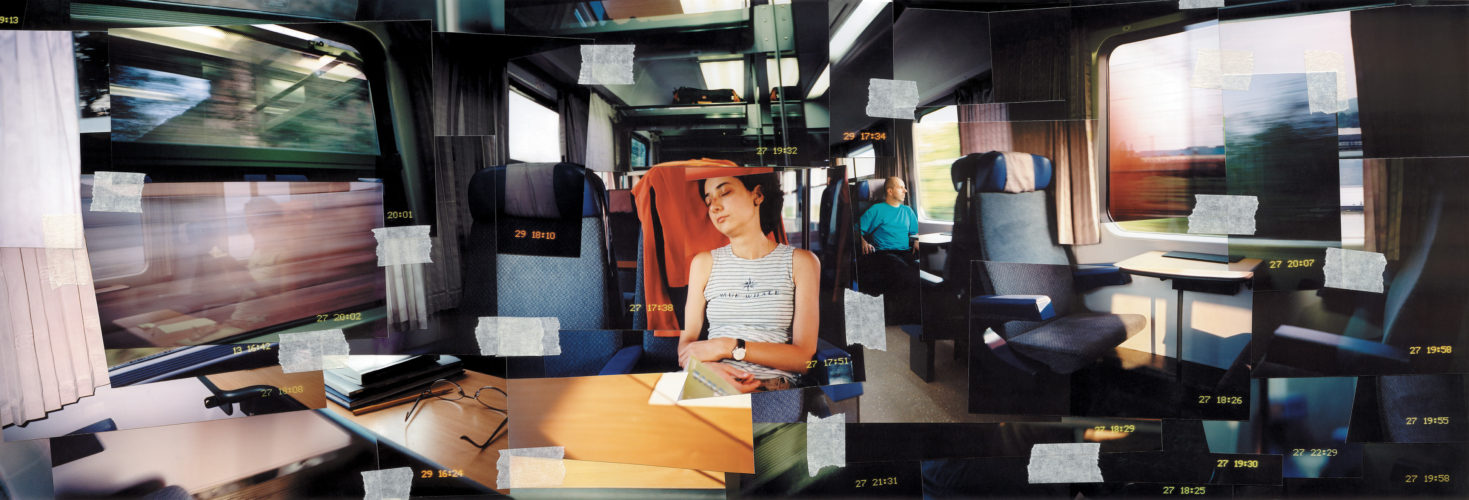

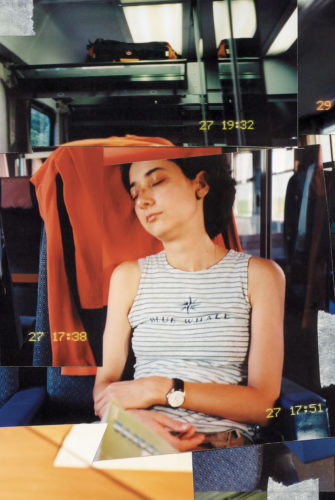

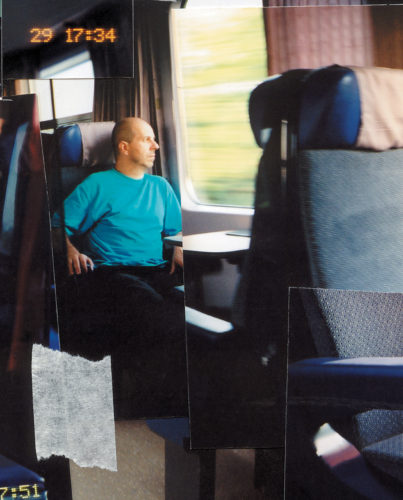

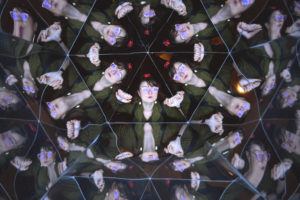

Iosif Kiraly fathoms the materiality of time in various artistic formulas: a metronome in Breathing in, breathing out, part of Old People Feel the Weather in their Bones series, makes one feel the monotony in which time drips for elders, especially when they are bedridden; the space-time panoramas in the next room, such as Intercity 593 or Synapses, Oltenita, coagulate several moments in time in one single space. The video works in the basement, however, purge time from its specific spatial coordinates, and have almost the mystical dimension of eternity, sweeping us from one place to another, in Traces of a Winter Morning, or swirling us in a caldron of rocks, in Rolling Stones.

In fact, Rolling Stones was, for me, the most surprising work in the exhibition, in its “arte povera” character, unexpectedly interrupted by brutal, site-specific materialism. Filmed in a Belgian concrete factory, in a plunge perspective, the work shows some spinning rocks, as they become smaller and smaller. “Rolling Stones is a metaphor for the way in which we ourselves chisel until we become dust”, explains Iosif Kiraly. The comparison with the commercial, “westernized” philosophy of Alan Watts of life as a water flow is on the tip of my tongue[2]. What’s surprising in this work is the site-specificity: projected onto the floor, it’s an open invitation to step on it. Convinced you’ll simply step on the projection of some spinning rocks, you’ll find some real rocks in a hollow in the floor, a veritable ontological fissure. It’s a playful paradox of materiality: what’s expected – as a result of the visible before the actual step – is a copy (a mere moving image on the floor, as we often find in commercial centres, for example), while in interaction we discover the real (real stones), hidden like an “Easter egg” within the copy. “Mindblowing!” I said to myself, a poor post-digital work that innovates through this material surprise, this palimpsest of the real inside the copy.

Initially, the video was supposed to be “traditionally” on a wall, but “Cristina had the idea to project it on the floor”, explains Kiraly, and “we found that hole”, in their step-by-step and site-specific work. “It’s part of the beauty of the process and if you knew right from the start how it would look, it wouldn’t be that interesting”.

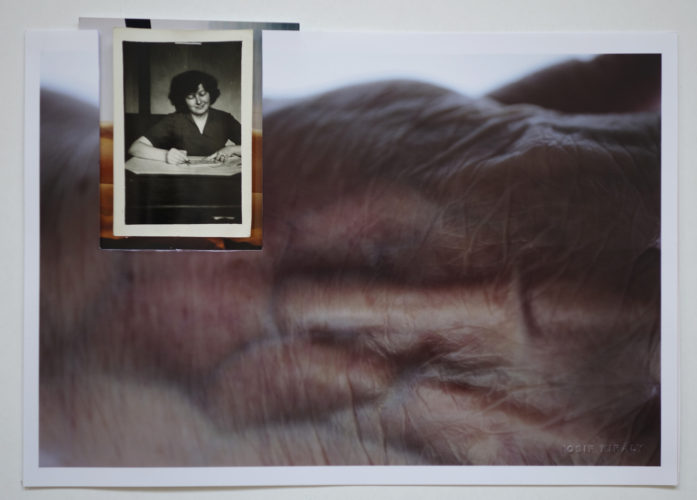

Old People Feel the Weather in their Bones and their close ones in images

My chat with Iosif Kiraly started from the works Old People Feel the Weather in their Bones series, upon which we lingered a while, probably due to a common fascination for the passing of time – enhanced by the quarantine – as well as some similar familial experiences, to some extent. Consequently I find out that a large part of the artist’s photographic archive started from his personal experience as a commuter between Bucharest and Timisoara. “My parents were in Timișoara, in 4-storey blocks, without an elevator. There are many elders in this situation, having moved in their youth, they discover that they cannot walk up and down the stairs when they age. So, I decided to bring them to live with us. Those were 12 intense years, I observed them degrading”, confesses the artist.

Kiraly has a rich history of working with his personal archive, yet this time he seems to have gone further in his private space. “I don’t do activist art, but I want to have a contextual background”. His images are not political in the sense in which we are formally educated to understand the political (militant, large scale, lacking emotion and in fixed, “wooden” tropes); but in a more profound sense that concerns us all: that of the private space understood politically[3]. The story of Old People Feel the Weather in their Bones series is, in its essence, a common one: how do we manage old age within the family, when social structures have transformed against extended families and while recent social politics not only invisibilise it but also use it as an instrument for capital/ electoral short term gains. It is painful to watch the degradation of our own, but as long as we don’t normalize aging and reduce the stigma around it, we won’t be able to place this subject on the public agenda, for real, systemic changes. Read in this key, Kiraly’s series facilitates this normalization and destigmatisation.

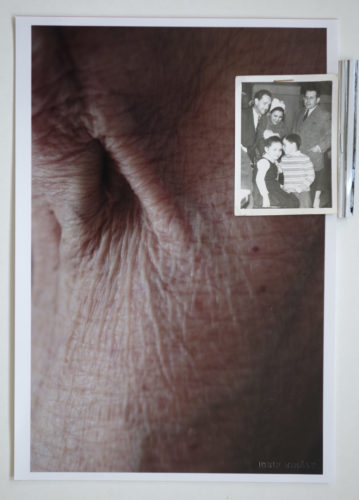

Old People Feel the Weather in their Bones is a meditation upon the passing of time upon flesh, in diptychs or collages, “mises-en-abymes”[4] in which we find the same elements, only that they’re marked by the passing of time, through discolourings, contortions, wrinklings or, at least, different photographic techniques. Emotionally, “it is a sad series”, but aesthetically “the old body is more spectacular, in macro-photography, than the young one”, thinks Kiraly.

Without a direct, assumed connection, I see a tight conceptual-aesthetic affinity between Iosif Kiraly and the defunct Agnès Varda. The director was also fascinated by the markings of time upon bodies and by the “horror” of her own, which she didn’t recognize anymore: “I have the impression I am an animal, even worse, an animal that I do not know”[5], as she confesses in the famous Les Glaneurs et la Glaneuse. At a microscopic level, the images stand at the border of the human and the non-human, they are sceneries within the heterotopic spatiality[6], in the context of social and discursive marginality of old age and illness. The photographic gaze has here a haptic[7] attribute, caressing from close to closer the variations of the wrinkles on the skin. If such close framings detach the subject (the skin) from the entire spatial-temporal context of the character, transforming the personal photography into concept, Kiraly additions older family photos, in order to close the circle of meaning back into his family history.

What matters for Kiraly is not only the aesthetic but also the context, on which he sheds some light: “when they were your age, all opportunities closed for my parents and they had to start again from scratch. And even so, in a rigid, Stalinist regime, they knew how to feel good and to live intensely”. Hence, he chooses the collage to complete the landscapes of skin with family histories, only to add to the mystery of the entire composition, creating a “back-and-forth” through time, among fulfilled or lost potentialities.

Fantasy-memory. Fragmented narratives connected by threads

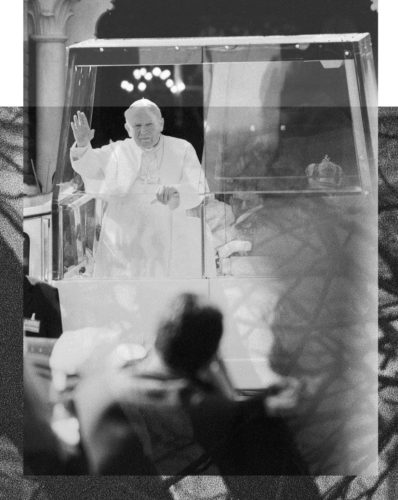

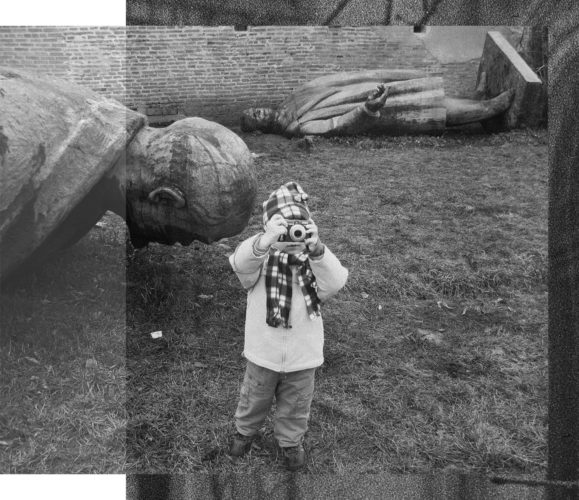

Passing into the other room of the gallery’s entresol, we encounter 7 other more known works. The exploration of the passing of time is developed here from a different angle, that of the post-factum construction of the “decisive moment”[8], by gathering different timings in panoramic works. Fragmentation is a condition of (contemporary) life, but there are red (or blue) threads that tie coherently all pieces together. This series focuses on the multiple ways of seeing: panoramic, closely or through time. The work titled The Act of Seeing is a meta-look through which the artist interrogates his own process, transforming it into an accessory work for Reconstruction – LA Getty Museum. The latter is a fictional panorama constructed from different frames, part of which we can see separately in The Act of Seeing.

“1% of the photographs end up in the work, the salt and pepper. You need a character, a relationship from which to build on. Sometimes, images from different visits in the same place pop out, or even from different but similar places”, explains Kiraly his work process.

The works are visual explorations of the processes of memory, as fantasie-memory, “some (attempts of) visual representations of the manner in which we remember. We never remember with the same details, details can be from other places as well, maybe even things we haven’t in fact lived through, but which seem to belong to that particular situation”. Kiraly is deeply fascinated with mnemonic processes, challenging them visually, through purges and (re)constructions of a fictional decisive moment, sometimes in several variations of the same work. Some people captured in the work were actually posing, but for a different photograph (will such works still possible, legally and ethically, under GDPR?).

Here, the central subject is the flux and reflux of memory and the modalities in which these waves extend psychological time bringing debris from elsewhere. “Memory is a fantasy. It’s formed from objective bits, let’s say, but the final product is a fiction, a symbol in the brain which, when interpolated, opens other doors, brings in other elements”, says Kiraly. Ontologically, memory is too compromised by complementary psychic processes, such as déjà –vu or false recognition, in order to consider objectivity (besides the purely subjective standpoint of the viewer) or integrity throughout time (we could say that each time we remember a certain thing, the memory is different). Thus, Kiraly explores visually these processes of emotional memory to provoke synchronicities, such as, for instance, the blue characters that look towards industrial landscapes in Synapses, Turnu Severin.

Complementary to the fascination for the memory processes is the fascination for trains, which he regards as capsules in which time has a different passing, in its 100km/h compared to the time outside the train. At the intersection of the two an accumulation of temporalities emerges, “forced” in the same image, where space seems continuous but time is discontinuous (for example, in Intercity 593, Aurora Kiraly appears twice: once sleeping and once reading, as a reflection in the window).

Transparency, achieved digitally, is what helps him represent the way in which memories become diffuse: “time passes, details are lost”. In this manner, various trajectories of meaning can be created between the original and the copies: “like Ansel Adams said, the negative is the score and the print is the performance” (Kiraly). The way in which the image emerges into the visible can differ (a little or a lot) each time.

The fragmentary aesthetics of Kiraly gathers, like the memory streams, modern and contemporary elements that complete a poetic universe, cvasi-realistic and cvasi-fictitious, like an ideational premonition of fictional photographic images composed by AIs[9].

Personal backdrop

Iosif Kiraly graduated the University of Architecture, but he considered this wasn’t an appropriate profession for him: “it was too complicated, you had to be like a director, you depended on the producer”, that is, on the financial resource. “I preferred some humbler things, at a smaller scale, in order to not make compromises”, but the choice was not on the likes of the family: “even though I wasn’t depending on the anymore, it was a blow to their dream of me being an architect”. “You have to take some risks, you can’t go on safe mode”, and “in the 90s photography was like hairdressing”, continues Kiraly. In the end they understood, but his father never came to any of his exhibitions. However, Kiraly remains a strong supporter of young people, being among the founding members of the Photo-Video Department at UNArte. He is also one of the founders of RO-Archive, a platform for documentary photography dedicated to the transformations of the post-communist urban space. The documentary and the artistic photography feed each other constantly. “I work in two timings: on one hand the accumulation of material and on the other the projects I already have in progress”. During the quarantine, he dedicated his time to his personal archive, “which is so rich to support work production for the rest of his life”.

The exhibition Letting the days go by, water flowing underground was at Anca Poterașu Gallery during 13.06 – 11.07.2020.

[1] https://aoc.media/opinion/2020/03/29/imaginer-les-gestes-barrieres-contre-le-retour-a-la-production-davant-crise/

[2] This should not be read in a deprecating manner, Watts’ books can be for some helpful instruments in times of spiritual struggle, but most probably his perspective, as an outsider in Buddhist culture, essentialise a profound spirituality, untranslatable to the universe of meaning of the Western reader. Can be read as self-irony to my own mental reference.

[3] „The personal is political”.

[4] Process in which one work is embedded into another, such as one image being retaken in itself.

[5] “C’est-à-dire c’est ça mon projet: filmer d’une main mon autre main. Entrer dans l’horreur. Je trouve ça extraordinaire. J’ai l’impression que je suis une bête. C’est pire: je suis une bête que je ne connais pas | “I mean, this is my project: filming my hand with the other. Entering the horror. I find it extraordinary. I have the impression I am an animal. Even worse: I am an animal I do not know” – Les Glaneurs et La Glaneuse (my own translation)

[6] Foucaultian concept referring to certain cultural, institutional or even discursive spaces of alterity, worlds within other worlds, similar but tormenting, disruptive

[7] “The vision is a close one, the space is not visual, the eye itself has a haptic function, not an optical one”

[8] Henri Cartier-Bresson’s term

[9] Realistic images made up by artificial intelligence are multiplying ad infinitum, we already have a data base of non-existent human stock characters (here). A more detailed article about the implications of this practice, or one in a more technical key, here.

POSTED BY

Raluca Țurcanașu

Raluca Țurcanașu is a former Account Manager who wanted to write. She's trying to blend visuals and words to tell compelling cultural stories. Raluca has been following image studies in Bucharest (C...

ra-luca.me/

Comments are closed here.