Large shows with full on researched content and a statement growing from same-level voices, against the backdrop of the surface-based, colourful & performative-depressive art of the posthuman era, where statements are made with a song and often melt into the filtered air of Instagram. A judicious choice in he case of the OFF Biennale, given the suspicion with which its second edition was awaited. After what the artworld interpreted as a spontaneous and very loud political shout against the current fascist regime in Hungary, the second edition could only have become a failed attempt to replicate the freshness of the first or, at best, an overdetermined political positioning which would have alienated artists and given too much credit to politics.

The previous explosion of over 100 shows in the city was replaced with a tightly curated selection of 40 projects, orchestrated by a core team and produced in partnership with the hosting institutions (mostly off spaces and private galleries, but also foreign cultural institutes). Quite importantly, all the projects were chosen to respond to this year’s theme, Gaudiopolis (City of Joy), and often the core team co-curated shows or events. The result was the simultaneous activation of all the important spaces in Budapest, which made the city look like an art haven.

The choice of the theme reflects, in my opinion, a typical evolution of our generation. The initial outcry, a direct response to injustice, voiced out by angry young people who know they can make the world a better place, is flattened out by rhetoric and financial cuts. Then follows a period of self-criticism and many get lost along the way. But those who continue understand that the fight requires new weapons and a re-evaluation of our old ones, the ones we have been handed over by previous generations. OFF is attempting to feed joy into the machines: joy understood as new horizon, recovery of a short period (1945-1947)when Budapest was the seat of a mostly Jewish children’s republic based on equality and help among its members who had been rescued from the War, organised by the anti-Nazi Lutheran pastor & resistance hero Gábor Sztehlo. Surely, an episode cropped to the current needs so as to highlight inclusive community work, regardless of its links to institutions we no longer trust in, such as the church.

Many of these ideas coincide with similar localized attempts all over the world, each drawing on a chosen past and incorporating the findings of the present. Truth be told, there is no real joy in any of these attempts, nor is there in Budapest: joy is more like a code word for work, research, moving away from immobility and depression, joy as non-despair, so at least a first step away from criticism, from deconstruction, from being crushed by our own weapons. The premise is also something one can experience in Romania – only, I have to say with regret, we are not able to move on and take the step that requires collective work.

The projects make a point in observing the theme closely, something which one rarely encounters at an event of such scale. And I do not mean observe in the way that curators respond to themes like viva arte viva in what are now essentially luxurious displays for even more luxurious goods. Here, there was a clear effort to make content significant, to counter neoliberal claims that the past doesn’t matter or that surface is the message. Such claims have poisoned our imaginary and weakened the power of art; they have left us jaded in a world we wouldn’t even choose to save (see climate change deniers).

Attending the opening weekend meant rubbing shoulders with the entirety of the independent scene, reunited on the occasion, and during the two weeks I spent there, I had the opportunity to meet and talk to many of those involved. The “anti-biennial” claim surely comes from the low-key choreography of the entire event, attended mostly by the small and receptive art scene, local loyals and friendly foreigners – in short, approachable people, not the daunting crowd of the global biennials and fairs.

It seems as though the event was an opportunity for Hungarians who in recent years felt compelled to leave the country to return and feed some life into it. Forecast of a Broken Past is such a project, curated by London-based Borbála Soós and featuring foreign artists (among whom UK darling Andy Holden) alongside Hungarian stars such as Tamas Kaszás. The show looks right into the question of how future communities can be built: what are the tools we can choose, between anarchism, sincerity/irony, utopian modernism, humor, research, pop culture and other such overlapping notions that the previous generations passed on to us. Advocating the rediscovery of a valuable heritage instead of a radical break that would alienate tradition, the show is in tune with the biennial’s goal to look for connections instead of cracks. The quiet and respectful show, cut across by discontentment with the current situation, was representative for the position I highlighted above.

There were a few clear themes running through the biennial: community work, alternative education and play, critique of nationalism and national myths (with a specific focus on the Trianon Treaty and its aftermath in contemporary conscience), the historical legacy of the Nazi period and the Second World War. All the themes are located in Hungary’s past, which is plowed with the stated purpose of finding appealing ancestors, and the implicit one of presenting to the world a better Hungary, aligned to the (art)world’s expectations of a free, inclusive and radical community.

Two very good archive shows, Somewhere in Europe (CEU Archive) and City Theatre (taking place in four galleries: Csendes Társ, Kisterem Gallery, Trapéz Gallery and Vintage Gallery), documented the Gaudiopolis moment and street performance of the East-European neo-avant-garde, respectively. Also in the documentary vein was Sari Ember’s video research of the second generation Hungarian community in Sao Paolo, showing these elderly members singing patriotic songs learnt in their childhood.

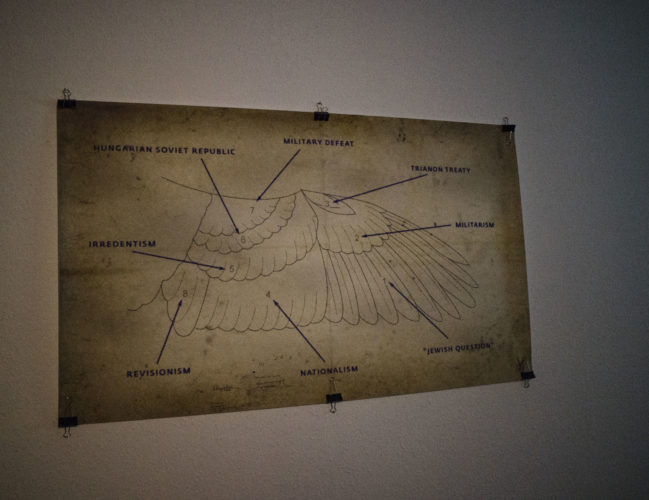

My favorite take on what we could call ‘Hungarianism’ is Szabolcs KissPál’s Hungarian Trilogy, a touring exhibition inventorying Hungarian national symbols and myths dealing with the Treaty of Trianon and anti-semitism. The exhibition encompassing two films and a museum-like display, hosted at the Institute of Political History, is working through them to understand their connections and continuity: in the end, Hungarian nationalism emerges as nation-religion. Though shot through with humour, the work is very dark, in contrast to a parallel take on the issue of Trianon’s legacy for the young generation, For me, Trianon… at Chimera Projects. The four curators asked artists from the countries affected by this event to send works that would perform the historical understanding they have of it, but also the place it holds in their personal history. Most of the works tended to brush over the political implications highlighted in KissPál’s extensive research, and instead focused on personal ways of coping with such overpowering events: ironically suggest that all sides are equally manipulative of it, see it as a fertile ground for new political seeds to grow, work the nostalgic vein, etc. What is interesting to observe is how the individual may hope to confront history: despite the rhetorics that it all starts with us and that every little gesture counts (specifically deployed in issues such as recycling and energy saving), one can observe that even a collection of such simple gestures is light when considering the need of unpacking the meaning of large events. For it to be efficient, the Trianon exhibition needs to be read in the larger context of the biennial, and certainly together with the Hungarian Trilogy.

*

The question of funding this extensive program is central. For its first edition, the biennial was run on an entirely voluntary basis and everyone expected this to change for the 2017 edition. Working for free is dangerous – people think you can and will always do it. The fact that the second edition was again scarcely funded, with only the core team and invited artists receiving payment, annoyed and partly divided the large team. Even though about a third of the projects were chosen based on an open call, with the conditions clearly laid out, this did not prevent resentment.

State funding was a central target in 2015 – until this day, all the spaces and artists involved with the biennial are boycotting state institutions, either by not applying to funding or by refusing to participate in their program. They would not be receiving much state support anyway. A recent law stating that externally funded NGOs (including the organization running the biennial) declare their status is a new means of blacklisting organizations that do not work with the state. On the other hand, many galleries receive state support, including those hosting OFF events. Before raising your eyebrows in face of “complicity”, imagine for a second your home scene without state funding – as an exercise, I though of Bucharest without AFCN: misery. The only scene I have researched so far where the state has absolutely no merit in the development of the arts is Indonesia: the solution artists found was precisely to work in self-funded collectives. There is no such tradition in this part of the world – I was amused at artistic duos (ex-artists collective or Lőrinc Borsos) that introduced themselves as collectives, whilst in Yogyakarta collectives start at 10 people. The exercise OFF is attempting is complicated also because we don’t know how to do things differently – we have always been individual art professionals supported by a powerful state which we could use as backdrop for political and aesthetic actions.

In Eastern Europe, artists seem to be reluctant to look beyond the first layer of problems – corruption, lack of funding, discretionary support, political naming, etc. – and accuse the more fundamental issues of the neoliberal system, tightly connected in this part of the world with self-colonization, and later colonization. On top of this, Hungarian artists are living under the acute stress of rising fascism, which is deeply troubling on a day-to-day, even intimate, level. Economic and ideological issues are immediately connected and subsumed under the figure of Fidesz – and artists, when they are not crushed under the weight of having to deal with this powerful and sly enemy, are left with attacking it with their meagre weapons, which may scratch its surface, but very rarely address the core. It seems as though, in such times of distress, one has to be less picky about their friends – hence, the Biennial was criticized for teaming up with the private (read: commercial) sector, thus questioning the very idea of an independent event. Basically, independence translates as independence from the (Fidesz-controlled) state, thus obliterating the core issue, which is the neoliberal ideology, taken to its contemporary extreme of fascism, populism and illiberalism, of the ruling party. The state is just as neoliberal as the private owners behind the art galleries in the biennial, the two are ultimately on the same side – the side of hierarchy, hegemony and generally everything that the content of the biennial turns against.

However, I am not going to say that this invalidates the entire biennial, especially since, after having analyzed the content, I can see that these issues were battled against until the logical end, and that alliances were made as carefully as possible. No one can face neoliberalism alone and win – and I dislike those who sit on the side and criticize without ever risking to make mistakes, mistakes that at certain times might seem like they are invalidating the fight. OFF attempted to fight against both the content and the methods of the current political system, and managed pretty well on both accounts. Of course, the entire team is now exhausted, reviewing their priorities, saying that if the situation doesn’t change, they would not do this again in 2 years, and so on. However, I would say that the entire point of the biennial is for it to continue into its third edition – what is more, this edition should attempt to address precisely what it left out in this second one (which already addressed much more than the first one): the regional forms of neoliberalism, meaning an understanding of the situation in Hungary less as a local drama and more as a manifestation of global politics on the ground prepared by transition, atomization, isolation, etc.

In this respect, I think that art professionals in the neighbouring countries should respond to the call implicitly put forward by the organizers of the biennial and redirect projects, funding and human support towards the next edition. OFF theorized and enacted the commons, but within the isolated Hungarian culture. The fact that they could not predict the full range of criticism and impact shows that their premises were correct: atomization is the wrong position against neoliberalism, one needs to be part of a collective mission in order to receive a voice. Moving from the local to the regional level, we can say that a regional cooperation in view of the third OFF biennial would turn the discrete voices into clear messages, would boost the organizers’ morale and have impact on the regional players as well. During my first trip to South-East Asia this year, I understood one important thing: a region, even though a (colonial) construct, is a powerful configuration on the global scale. Eastern Europe is not a construct to be built, it has been here for a long time already, whether we like it or not. Instead of debating its relative borders, we should start to use it in our own manner and to our own good. A transnational cooperation in the case of the third OFF biennial would be an interesting and perhaps important test, a move away from our self-colonialism and an attempt to build relevant tools for structuring our world.

Further down the line, this move would perhaps make OFF aware that the questions that they are asking are not art questions per se – they are precisely the questions of the entire society. Thus, OFF artists, curators & organizations should look for allies less in privileged owners and funders, who might facilitate material displays but with whom the political & symbolic cooperation does not undo the current impasses, and more in the other groups who are suffering from the dominance of the privileged of all kinds, state or private. Fascism makes us forget who are the ones that suffer and segregates communities who do not share the same vocabulary anymore to express their pain, turns them against each other so the real oppressor is obscured. The artworld is one of these splinters from the community, an entity separated from the others and expressing its anger at the government and those who brought it into power, thus forgetting its role as one of the layers within the community charged with creating an imaginary of resistance.

OFF-Biennale Budapest is on between 29 September – 5 November, 2017.

I would like to thank everyone who took the time to debate the arguments in this essay with me: Gergely Nagy, Barnabas Bencsik, Flóra Gadó, Júliusz Huth, Martyna Nowicka, Piotr Sikora, Csaba Nemes, Ion Dumitrescu. My special thanks to G. M. Tamás.

The residency in Budapest was part of the project East Art Mags and was made possible with the support of AFCN and ICR Budapest.

POSTED BY

Cristina Bogdan

Founder and editor-in-chief, between 2014-19, of the online edition of Revista ARTA. Co-founder of East Art Mags, a network of contemporary art magazines from eastern and Central Europe. Runs ODD, a s...

www.evenweb.org

Comments are closed here.