The revolution can’t happen without equipment. To overthrow a system always requires tools – from farmer’s hoe to video games to poetry. But what is the nature of these tools? Action requires weapons. The system is strong. Sadly, the nature of those tools often compromises its righteous cause, making it all the more important to question their nature, and the position they (unconsciously) uphold.

Veda Popovici’s work Revolutionary Gear uses the tool of re-historicisation – or re-narration – of art history as a starting point for a revolutionary feminist discourse. The work contains three items: a table of research into art history hacked with hand-drawn additions by its new author, a series of masks in the form of downward-pointing triangles, and an instructional video in which Popovici demonstrates how to wear the masks as a voice-over reads a series of provocations connecting to the history of Malevich’s Black Square (1915); the frame upon which the new art history is based.

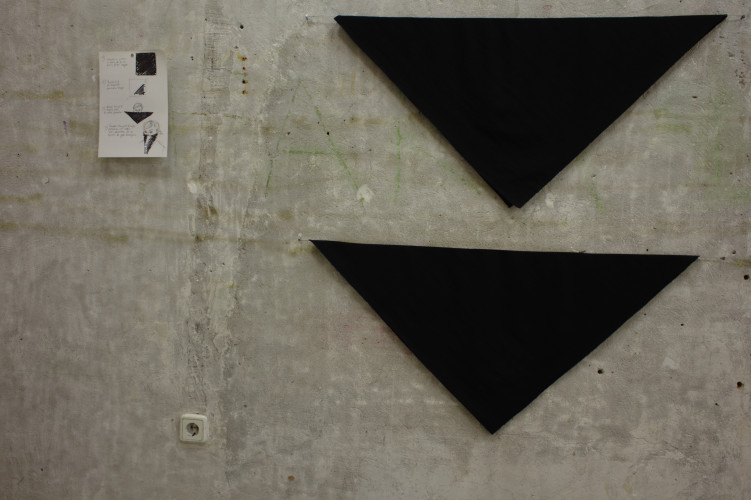

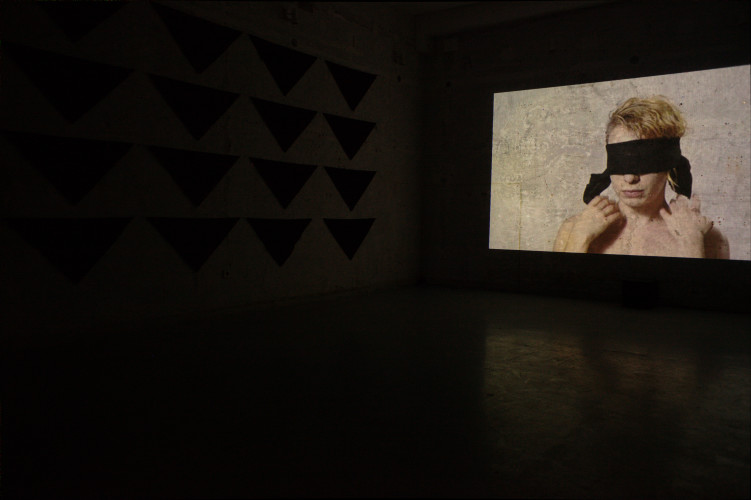

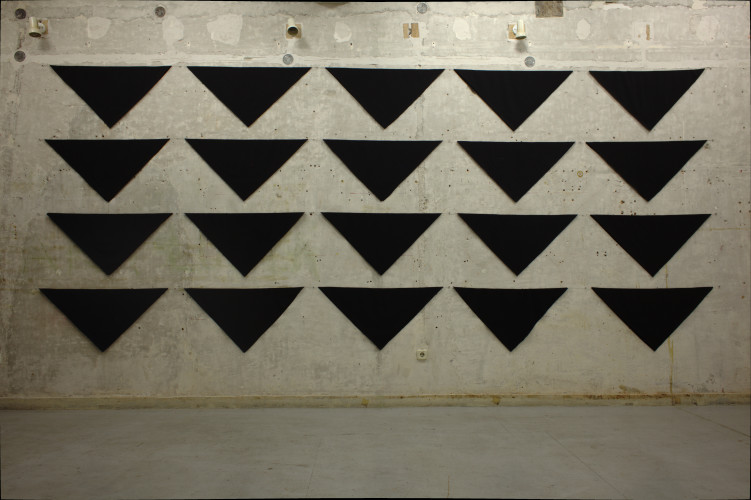

Each work is presented with crystalline simplicity. The series of triangular masks is perhaps the most arresting – dominating the bullet-holed concrete wall of Atelier 35, and dwarfing the spectator. They appear as if in a formation – a kind of Roman Testudo – staring down upon the spectator and indeed, ready for battle. As well as referring to one variation of Black Square (being literally a black square folded in half), they combine into an overpowering site of speculation, suggesting an encounter with dominance, a formation of a structure against a structure, at the same time suggesting an obvious invitation: ‘join us’.

The instructional video A History of Art Retold Through the Black Square is a kind of manifesto, touching on the patriarchal nature of various canonical western artworks as Popovici simultaneously demonstrates the possible ways to wear the triangle, not accidentally referring to its historical use to conceal, disguise or cloak the body of a woman. The various symbolic modes are represented, from worker’s headscarf (tied around the back of the head), to the traditional housewife (tied underneath the chin), to a Roman toga, to burqa, to ninja mask, to its final authoritative rendition – a kind of gunslinger, perhaps a re-appropriation of the macho cowboy.

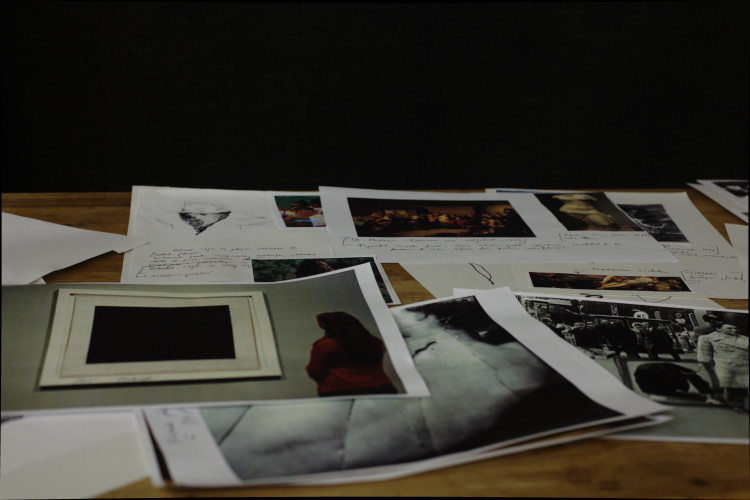

On the table in the corner, some delightfully low-brow stapled sketches, clippings and prints detail the artist’s research, with her interventions (as frustrated scribbles, circles to bring your attention to something, or doodles) serving to highlight the patriarchal structures dominating their interpretation, and their positioning, representation and viewpoint of the woman – together with instances such as suffragette Mary Richardson’s 1914 slashing of Velázquez’s Rockeby Venus, perhaps as a guide, clue, or inspiration. The focus on the gaze is common to contemporary feminist discourse, and provides a useful platform for some of Popovici’s more interesting claims, such as regarding the false neutrality of law (“The allegory of justice is a blind-folded woman”). A sense of disobedience provides a lighter tone to the sense of threat pervading the work.

To this end, a fascination with militant feminist tactics pervades Revolutionary Gear, in particular the question of violence and social change, tempered with the desire to empower and to educate. The artist’s body of theoretical work is massive, supporting the claims made in the work itself. It is certainly no accident that over the course of the instructional video, Popovici at various times looks like contemporary depictions (and misguided conflations) of terrorism – and indeed, she suggests that the ‘threat’ of the work is its most potent component. Here the artist encounters an age-old paradox: how to initiate hegemonic change, so desperately desired, even required by society, without the use of violence? Is such a thing even possible? In such a violent system, non-violence seems so, well, weak.

But that is not to suggest that the struggle, the very specific struggle, taken up in this work is the same as others. Staring into the legion of battle-masks, it would be easy to mistake the pervading feeling as one of aggression. More accurate, perhaps, is a kind of aggressive defense – a refusal.

Such a reading invites an obvious criticism: that in addressing the power structure with such vehemence, it may serve to reinforce it, though to argue this would itself require an embedded patriarchal position – the work is not aggressive without intent. If there is anger, it is an anger born of consciousness, naturally followed by an extreme sense of injustice – at what was taken away, but even more so, what continues to be taken away. We live in a world of such confused, populist feminist causes, where a film can be promoted with “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave”, and the clearest statements come from those protesting the premiere – free from the burden of upholding any dominant economic structure. Here, Revolutionary Gear is at its most active, in the suggestion that the struggle is not a means to an end but of significance itself. While the ‘gear’ here acts as suggestions only, the path itself is very clear. The black cloth, standing in opposition to patriarchy, could equally be blindfolds – indicators of the spectator’s privilege, and an invitation to remove it. As Popovici states to conclude the video, regarding Black Square:

Once the dream of an old revolution, I gave it a new sense, the only one that still matters.

The attachment of new meaning to Black Square is itself, perhaps, a kind of revolution. The re-historicisation is repeated in the artist’s borrowing from her own oeuvre – the triangles from last year’s LGBT workshop, the monumental nature of their presentation from Migrant’s Monument (2014), the attack on the supposed neutrality of law and the figure concealed in black derives from Story of the Fall #3 (2014). More than previously in Popovici’s works, perhaps, Revolutionary Gear has a reflexive quality, flirting with introversion, recycling concerns as if re-examining past decisions.

All very well – but the art activist must smash through this type of contemplation, and act, lest one more radical discourse become subsumed along with all the others, sucked up by capitalism. There is a missing element from Revolutionary Gear and present in all previous works of Popovici: an opportunity to participate – not an invitation to passively look, but ones that demands interference in a very material sense. As Richardson did, before us.

A participatory performance by Veda Popovici based around the work Revolutionary Gear will be at Atelier 35, Bucharest, Tuesday at 7.30 pm.

POSTED BY

Richard Pettifer

Richard Pettifer is an Australian director, critic, and theatre theorist based in Berlin. As a critic and artist focused on former ‘Eastern Bloc’ countries, he has been invited to many regional fe...

richardpettifer.blogspot.com

Comments are closed here.