As an almost visceral extension of the artist’s body, painting is a bourgeois, hermetic kind: it cannot be done by just anybody, especially when it is at least partially figurative. In order to paint, the artist must follow a few steps in technical and stylistic initiation, something that is not readily available for the masses that were deprived of the necessary preparation and dexterity. Roused up by a revolutionary feeling, the avant-gardes tried to produce “democratic” types of art, in order to eliminate the elitist distance between the art producer and the spectator. Their purpose was, as philosopher Boris Groys explains in the book of essays “Going Public” (2010), to put forward artifacts that are technically produced so easily, that anyone could make them, even a child. The famous painting “Black Square” by Malevich is an example of painting with a maximal transcendental extension, in a Kantian sense. In other words, this painting appears to be the proximate kind to any other, it is the work of art reduced to “a black square” on a canvas and a frame, the most schematic elements of a painting. Although the avant-garde wanted to approach all types of audiences with this type of schematic works, the result was a very unpopular one. If a child can paint such paintings, then they “deserve” to be despised, was what the addressed public thought. The more democratic the art, the more unpopular it is.

In reverse, if, for example, Adrian Ghenie’s paintings have become so popular in recent years, this is precisely because, among other things, they are not democratic at all. These paintings bring about a nostalgia for bourgeois art and for the artist that assimilated the “classical” canons of painting. Capable of making works for which he must demonstrate technical virtuosity and for which he must dedicate considerable amounts of time, Ghenie is one of those artists that are hard to imitate by the uninitiated spectator, thus he can hardly be accused of “cheating”, as was the case for a certain Damien Hirst, for example. The latter became an “entrepreneur”: he does not touch the artifacts during the production process, because the “alienating added value” (from the Marxist point of view) is realized by workers hired by the artist. An artist that does not create with his own two hands is often mistrusted by those less familiar with the evolution of contemporary art.

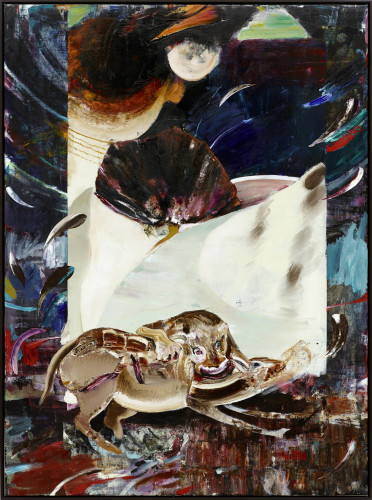

Although Ghenie is not an “entrepreneur”, like Hirst, he is situated just as far from the avant-garde’s democratic ideal, that being the timeless and transcendental gestures that reduce the artifact to a maximal grade of generality which makes it permeable to all eyes. This is how the avant-garde sought “the weak image”, the abstract image, not only to fill it with conceptual meaning, but to void it of space and time and make it accessible to all. Anchoring space and time in a painting, suggesting a scenario that needs to be decoded using intelligible cultural filters only due to a certain education, are the means with which a painter becomes accessible only to a category of initiated, thus elitist people. Ghenie’s elaborated canvases, partially figurative, of great size, require technical virtuosity and enact “forte” images that are anchored within a context, they are empirical, opposing the deliberate weak transcendental images of the avant-garde.

Only a “forte”, empirical image can have a narrative content, and the painter from Cluj invokes in his works scenes that are in agreement with the stylistic register. This way, consciously or otherwise, Adrian Ghenie undisputedly cherry-picks his audience: he is addressing a bourgeois category of people, nostalgic over grand modernist projects and “forte” images that are allusively loaded with the symbolic capital of the dominant western culture. The bourgeoisie’s mirror seeking to confirm its value with “forte” artifacts, Ghenie’s artwork, thus undemocratic, paradoxically becomes popular precisely by way of the absence of weak images. Because, ironically, an uninitiated audience saves its admiration only for that type of art that it is incapable of making. The plain spectator feels the need to be humiliated by the distance separating him from “The Artist”.

Analysing the narrative structures of works belonging to a painter such as Ghenie might reveal interesting things about his type of art and the artistic mediums he permeates, but also about the type of audience he is addressing. The artist recently started a collaboration with one of the most prestigious contemporary art galleries in Paris, Thaddaeus Ropac, where he made his début with a solo show that opened late October. Visitors could see ten new oil paintings signed by Ghenie, works that focused on a romantic theme: the artist’s self-portrait.

In “Self-Portrait as Vincent van Gogh” (2015) the artist from Cluj is confessing to a personal imaginary genealogy, claiming to be a relative of the Dutch painter. Just like in political hierarchies, the most well-known way of becoming famous within artistic environments is for an artist to claim something from certain established artists. Yet the collage that reunites an artistic self-portrait and a hint of a “classic” Van Gogh self-portrait within Ghenie’s painting is unexpected. Why would the painter from Cluj adjoin his image to one of Van Gogh? The Dutchman’s self-portraits are a testimony to multiple dramas: the evolution of a mental pathology (he seemed to be suffering from bipolar disorder), the unknown genius that is more and more socially marginalized, the extreme poverty that did not allow him to afford models for his paintings, thus forcing him to a painful dialogue with a unique artistic character – himself. Which of these profile traits could resonate with Ghenie’s story at the opposite end, the story of a spectacularly successful international artist that feels no anguish? The only explanation could probably consist of precisely this joining of two antagonistic artistic success stories – one of a painter that was ignored within his lifetime only to be recognized post-mortem, the other of an artist that became established surprisingly fast, right at the beginning of his career.

But this extremely fragile explanation quickly collapses once you contextually analyse the two stories. Van Gogh’s failure is justifiable due to the fact that, stylistically and narratively, he was working against the aesthetic canons of his time, he surpassed them, defied them, and presented new ones, as all geniuses do. There were no categories of audience that were prepared for his stylistic revolutions. On the contrary, Ghenie not only blows up the old “establishment”, he therapeutically, though undeclared, addresses a bourgeois audience who is worried about the post-modern dissolution of values, panic-stricken over the specter of democratizing artistic messages and losing their own privileges. He opposes the anguishing transience of contemporary art with a return to “safe” values, he claims a pictorial tradition that reunites established geniuses – Van Gogh, Francis Bacon.

If Ghenie often uses the artistic collage, quoting artists or slipping in various references to famous works, he does not do it in the spirit of post-modernity. His pictorial quote does not ironize or contrasts through “classical” image relativity and he does not transform kitsch and pop culture into art, like Andy Warhol. In other words, Ghenie does not make meaningful dislocations through quotes: he does not trivialize or corrode the classical, nor does he transcend the ordinary. He establishes an artistic genealogy of prestige in order to self-legitimize himself. Ghenie opposes temporary installations and short performances with the longevity of painting and his self-proclaimed spiritual link to various geniuses. The bourgeois public is relieved by these claims and feels that it is investing in already established values. And these values serve to confirm the artist’s identity which is sometimes threatened by various left-wing discourses and the transience of contemporary art.

As startling as this contrast between two artistic biographies juxtaposed by Ghenie is, him referring to the totalitarian European specter is just as surprising. In most art show presentations, or the curators and gallerists’ discourses, the painter who now lives in Berlin is highly recommended via recent Romanian history – communism, Ceaușescu, transition etc. In turn, Ghenie frequently invokes in his paintings important characters of the totalitarian world of the 20th century. The hinting to this realm is also part of the predominantly western culture paradigm, and the whole situation is a classic example of symbolic self-colonization. The West needs a clear opposition to an exotic, “uncivilized”, poor, troubled and bloody “East”, in order to strengthen its identity and value. The communist eastern past that Ghenie claims with these paintings is not in lying, it is inevitably distorted by the West’s romanticized and exotic vision of Ceaușescu’s land. The Romanian artist offers the West precisely that image of a faraway Romania that was expected, confirming its convenient and dominant stereotypes.

Stylistically, as well as through his narrative structures, Ghenie wins a bourgeois western audience by offering an illusory therapy for its post-modern neurosis. The relativity, the dissolution of the poles, the values, and the social homogenization that make up the post-modern project, are threatening this audience and condemns it to anxiety. This is why it will compulsively invest in a type of art that is capable of providing, for at least a little while longer, the illusion of its eternal privilege.

Adrian Ghenie, “New Paintings” was between October 22nd – November 26th at Thaddaeus Ropac Gallery in Paris.

POSTED BY

Lucia Popa

Lucia Popa is a PhD researcher at Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales (Centre des Recherches sur l’Art et le Langage) in Paris and teaches at Science Po Lille. She earned a PhD degree in So...

1 Comment

” In order to paint, the artist must follow a few steps in technical and stylistic initiation, something that is not readily available for the masses that were deprived of the necessary preparation and dexterity.”

this goes for tailoring, also

“This is why it will compulsively invest in a type of art that is capable of providing, for at least a little while longer, the illusion of its eternal privilege.”

If they have the money to “invest” in Ghenie, maybe their “eternal privilege” its not so much an “illusion”, ha?