– And, knowing it won’t happen any time soon, I donated almost all of my negatives to the Engravings Department of the Romanian Academy Library.[1]

Nicolae Ionescu – interwar photographer

– And I decided to stop waiting and create my own, online.

Alex Gâlmeanu – contemporary photographer

– And I went and saw as many photographic archive museums and galleries as I could in order to get the know-how. Just in case.

I, Raluca Țurcanașu – researcher and conceptual photographer

– And I tried to do a research project at the Engravings Department for my master’s, but in the end, I wasn’t allowed in – the bureaucracy was too much.

One master’s student

– And we chose to manage and make use of the Mihai Oroveanu collection because “even though photography has become an integral part of our daily lives, reflections on the role of images in society and their historical evolution remain minimal.”

The team of Salonul de proiecte.

At the end of last year, in October, Salonul de proiecte opened its first exhibition showcasing the Mihai Oroveanu collection. It follows the curatorial path outlined by the late Mircea Nicolae, as he presented it in 2019 for The Absent Museum. In his curatorial statement, Mircea Nicolae wrote:

As has already become obvious, museums in Romania are faced with multiple problems, shortages, and inconsistencies, both internal and external in nature, while major image collections and works of art are destroyed or lost without being co-opted into any mechanism to preserve them and place them in the public sphere. It is well known that Mihai Oroveanu, who built up this collection of photographs, wished to establish a museum of photography in Romania.

Many have entertained this institutional dream and yet it never materialized, so that each tried to realize it through their own means. The project that the team of Salonul de proiecte (Magda Radu, Alexandra Croitoru, and Ștefan Sava) organized is part of this common dream, but, unlike similar initiatives, its materialization is professional, and the display, research, and associated events are of European quality. However, despite being essential in this context of institutional lack, the exhibition series did not receive the necessary attention in the press, and so I felt the need to look more closely into it and the whole context. What you will not find in this text is an analysis of an image corpus – but I invite you to browse through it, online or in the space itself.

I constantly think of it. The part of our history we do not know.

I wanted to open my dialogue with the team of Salonul de proiecte starting from Ionuț Cioană’s statement, in order to understand the curatorial concept in as a long-term project and to see what continuities the curators decided to preserve:

Our collaboration with Ionuț Cioană was extremely special, and his finesse as an artist and theorist will always be an inspiration for us, not to mention his integrity and the absence we now feel, both on a personal and a professional level. Ionuț approached photography from the perspective of a contemporary artist “armed” with theory and analytical insight and with a great appreciation for photography. His exhibition ended our first project with the Oroveanu collection. The prospect of an institution dedicated to photography was on our minds even then, and his proposal was based on investigating the medium itself, on its physicality, we could say, seeing photography in its high and low aspects, both institutionally legitimated and part of pop culture, intellectually sophisticated and democratic. From these (multiple) perspectives we hope to continue to pursue the questions Ionuț left behind and to meaningfully contribute to at least one vision of a particular kind of future institution.

The Mihai Oroveanu collection is one of the largest private collections in Romania: it covers the period between 1850 and 1990 and works as a guide through the history of photography, a collection of small histories that nuance, or even decenter, the discourse of capital H History. Until the end of the year, the collection will be used in three exhibitions that “make visible a few broad areas of representations in the archive’s corpus, with a focus on architecture and the public space, representations of gender, and vernacular photography. Each exhibition will also be accompanied by three interventions from contemporary artists,” the curatorial team explains.

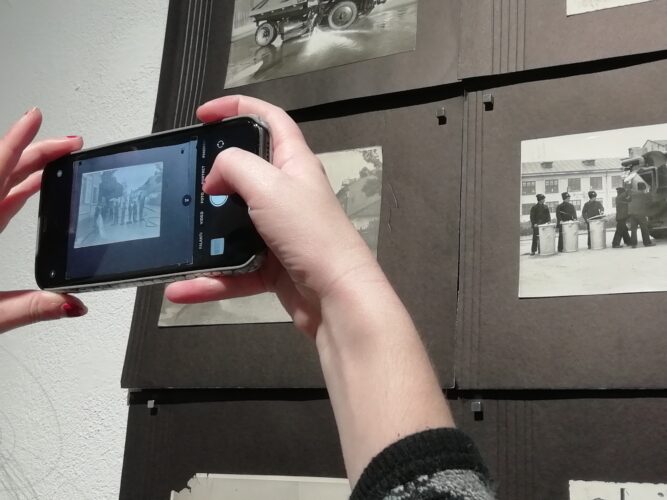

The exhibitions start from groups of photos put together by Mihai Oroveanu himself, focusing on anthropology (figures – gentlemen, ladies, etc.), industry, cities & villages, and Bucharest, also going into a more thematic organization to make the collection readable for future researchers. “To turn a collection into an archive, it must be accessible,” says Magda Radu during her guided tour.

Before going deeper into the implications of the curatorial project that Croitoru, Radu, and Sava have imagined/continued, I think we need to commend them for their perseverance in a pandemic context, managing to combine offline events (guided tours and individual visits to the space) with online ones (artist talks, available here) in order to make people curious to explore the digital archive (“The Photographic Image Between Past and Future”). It currently comprises 2121 images, but its administrators’ goal is to reach 4000 properly digitized and catalogued images available on photopastfuture.ro.

Deconstructing absence as a curatorial statement

I wrote above that the work practice of Salonul de proiecte is of European quality (for lack of a better term, I deliberately let slip this self-colonizing phrase). Why? Because the three curators’ mission is greater than simply filtering some old photos and because they do it impeccably. The rather limited space at Palatul Universul becomes a multifunctional (and truly functional!) hybrid, combining exhibition, storage, and research, and managing to remain clean and visually neat, a kind of white cube with functional elements.

We developed this structure specially for the exhibition and to allow for a more complex arrangement of the space we work in. It is about exhibiting the work that goes on behind the scenes – that was our main concept. It is a way of showing that the work that goes into any exhibition exists and it needs to be somehow recognized and understood. Institutions are constructed as neutral spaces, which hide their internal workings, and for us it is important to also show these workings. And there are also, of course, pragmatic considerations.

This architectural gesture becomes an elegant critique of the precariousness that cultural workers face, and I also read it as a political art gesture that not only addresses the lack of a Museum of Photography but also underscores the complexity of the invisible labor that goes into the entire archival ecosystem (which, locally, is practically nonexistent!). This approach is both deconstructive (by exhibiting the institution’s “bowels”) and constructive (by creating the functional structure of a miniature Museum of Photography). Exhibiting the structure (comprising boxes, files, shelves, image indexes) can therefore be read as a statement of good practice in terms of working with photographic archives on a local level. After being scanned and catalogued, the images are packed into the organizational model conceived by Mihai Oroveanu, so that the original intent (which encompasses this history of the precarity of visual knowledge) remains intact (European archive know-how points to cases of “malpractice” where collections were taken apart with the purpose of a more “efficient” structuring, which compromised their initial goals and trajectories).

We don’t have professional archivists – the material is very fragile. It must be kept in temperature-controlled rooms… there should be an entire infrastructure working towards preserving, researching, and exhibiting this historical material, which is now highly fragmented and hidden. Bucharest is a European capital, and yet it lacks an institution for photography, the curator also added during the tour.

Photography is rarely discussed in discourse around (material or immaterial) heritage. Those institutions that have important photography collections do not use or exhibit them. I wanted to better understand how the SdP team sees this dream that is always prevented from materializing:

The Museum of Photography is still at the level of a project that will likely not materialize any time soon, as the conditions necessary to found such an institution seem uncertain if not precarious. The local view on culture is rather conservative and complacent.

Photography is not seen as a real part of what’s called “heritage,” even though its contribution to edifying cultural heritage and collective memory is quite obvious. There is no national cultural strategy for protecting and working with archives and collections, private or even institutional. Funding is minimal and specialists are often vulnerable and distrusted. This is the unfortunate situation we find ourselves in. We, who are working on the Mihai Oroveanu collection, are still optimistic that we can make a difference in how work of protecting and using such a photography collection is viewed. At the same time, we try to stay connected to contemporary methods and issues.

The exhibition therefore becomes a manifesto-like gesture towards creating such a space, a kind of voila! or there you go! that does not just indicate institutional lack but also offers, through a transparent example, the necessary know-how for developing such a space. In other words, taking the exhibition as an MVP (minimum viable product) and scaling it in a larger space. And why couldn’t this space be the Tipografia Universul building? Would it not make sense to repurpose this space towards this purpose, given that the building itself used to serve images,[2] to facilitate, supervise, and perhaps censor their production?

The Museum of Photography. Out of love or for publicity?

If one looks it up, one finds that the Museum of Photography already exists as an initiative of Alex Gâlmeanu. In the aforementioned context of institutional neglect, his project is laudable for the consistency of its content, which focuses both on images and their historical context, as well as on photographic technique.

However, this is not an archival practice, but rather a mainstream project of raising awareness around the value of historical photography. Most photos do not have their source mentioned, but on the project’s Instagram page we see that the sources are public archives, such as Fortepan, Azopan, and Deutsche Fotothek (which does not stop the curator from watermarking his own name over each photo).

I would have expected this Museum of Photography to also reference and support other initiatives aiming to promote photographic heritage through its social media accounts, in the online public space. Instead, its complete lack of acknowledgment for complex projects like that of Salonul de proiecte, among others, shows that it merely capitalizes on public images (Fortepan and Azopan work under the Creative Commons license) for personal branding purposes. And, in a “traditional” marketing paradigm, this makes perfect sense, as Gâlmeanu is a famous commercial photographer (his page has 17,000 followers), and such actions undertaken “out of passion,” “with no personal interest in mind,” help grow his personal brand (especially through the shares his posts receive).

But, in the end, any archive is the result of a subjective process (and we must note that SdP acknowledges the interwoven subjectivities of the collector and the current curatorial team). In this sense, pop-scientific initiatives have their own function. But we must be able to differentiate between a popular project, like Gâlmeanu’s, and one that is theoretically informed, like that of Salonul de proiecte:

Photography is, as a matter of fact, a very democratic medium, but the main problem is that we live in an image culture that makes the image more ubiquitous and expendable than ever. In this context, we see countless examples of “beautiful” vintage photographs, shared extensively on social media, which are, in fact, drained of all meaning. Our mission is not to popularize photography, but to preserve a photographic corpus and to integrate it into a type of discourse that problematizes the photograph and sees it as a privileged instrument for reading both the past and the present, the curatorial team explained.

As any photograph is a manifestation of predefined layers of meaning (in the consciousness or unconscious of the photographer) that determine various relations and meanings for any viewer, so is the archive the result of an accumulation of values, priorities, and relationships that are not frozen in time but in perpetual becoming.

An archive is a political ecosystem of relations that intersect organizational culture, funding possibilities, the openness towards artistic intervention, exhibition possibilities, and research possibilities. The archival ecosystem encompasses all the logistical elements necessary to exhibit, acquire, catalogue and index, as well as catalogues, and databases, which can interact in order to uncover and dig deeper into certain segments of the collection. But this is where the political comes in: for these interactions to take place in an archive you need human connectors to work the archive and unravel these conceptual threads. And where there is no funding, the archive’s becoming is stymied, because archivists need to eat too.

However, in order to build a discourse around photography as an instrument of problematizing history (which is strongly ideologized in Romanian formal education) archivists need to pool their efforts, in the sense of building awareness around the importance of archives for collective memory. It would be nice to be able to visit a (traveling?) exhibition put together by Azopan, Salonul de proiecte, Alex Gâlmeanu, and other groups working with archives. In any case, I hope that the Calvinist pastor, the economist, and the programmer behind Azopan will follow contemporary models, like Magnum Photos, and will continue developing their project strategically (through content, events, publications, workshops – the whole ecosystem of instruments meant to put forth an archive’s collection). And this dream could be extended to the east, beyond the Prut, where the State Archival Agency is taking steps to exhibit its materials online (available here), unlike its Romanian counterpart, which has stagnated after releasing the Communism Photo Collection in 2008. Or perhaps the National Heritage Institute, a livelier organization more in touch with its audience will be able to do its part in facilitating such institutional connections.

I am still surprised to see that institutions in Romania are not properly set up to be able to adequately research and display photographic collections, which remain forgotten at best and destroyed at worst. I am also surprised to see how photography is often ignored in discussions around Romanian art history, and how photos still rarely make it to the walls of exhibitions, I was told by Gabriela Cherciu, a researcher and graduate at CESI, who I met at Salonul de proiecte during the guided tour. We may hope that this critical view held by new generations of graduates will lead to new projects, discourses, or even institutions configured around the vast Romanian photographic heritage, which today is mostly locked up.

Why is visual history so opaque?

Why isn’t it easier to access this knowledge around visual heritage? Why is it stuck either in locked rooms or in open URLs that are just as opaque in terms of navigation (UX)?

On one level, it could be institutional ignorance. But could we also read this opacity in a different way? Could avoiding Romanian historical photography be a consequence of the colonization of knowledge from the Global North towards the Global South? A consequence of self-colonization with “western” values? Walter Mignolo, the first person who explored the concept of knowledge colonization, builds his discourse starting from this statement made by Franz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth, 1961:

…colonialism is not simply content to impose its rule upon the present and the future of a dominated country. Colonialism is not satisfied merely with hiding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain of all form and content. By a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the oppressed people, and distorts, disfigures and destroys it.

Through internal and external processes, the ’90s have achieved this cultural colonization through new forms that came and filled the historical knowledge vacuum left in the wake of national communism. „…[A] common way of conceiving and affirming one’s identity [is] from a ‘bricolage’ of preexisting signs. These signs are, by their nature, products of the history of their use,”[3] writes Jean-Marie Floch. And then, if the “bricolaged” signs in the public space are merely a mass of shiny brands, hedonistic invitations, and commercial visuals, the hollowness of social identity comes as no surprise.

Sometimes archive images can also become marketing vehicles. If this is consciously and ethically acknowledged, it can be a (financial) help to the archive. But it can also mean a lack of professional ethics when it entails the extraction and use of resources for marketing purposes. An example of this “bad practice” is Covrigăria Luca, a brand that appropriated a photo taken by Iosif Berman which is part of the Image Archive of the Romanian Peasant Museum, using it as a branding tool for its shopfronts. I mention this unpleasant case in the hopes of avoiding similar situations in the future but also to explain why archive administrators are wary about publishing their archives online.

I kept asking myself what would have become of us if this visual heritage had been integrated into education, if it had accompanied history classes through text. But I also wanted to gain some insight into other people’s views, so I asked Adina Marincea, a media studies scholar and the contact person of the Oroveanu collection project:

From your position outside the curatorial team, but still close to them, what surprised you, what did you learn by looking at these historical images? In other words, learning history is often so verbal that the epistemic possibility of contextualizing history visually is worth exploring.

I for one never liked the way history is usually taught – highly didactically, with many years, numbers, and facts. I think it is important to construct narratives and interpretations for these histories, which are not just dull objective events, but subjective experiences, times in the lives of people like us. Outside of a few documentary films, paintings, photographs, and other archive documents, there aren’t too many visual representations of these histories in Romania, and the textual narratives one finds in history books for instance create a kind of detachment from them, a fragmented and depersonalized understanding. When visual representations are also present, however, it is easier to create mental images, to contextualize, and to observe the nuances and details that allow you to reconstruct the “zeitgeist,” or to notice potentially striking contrasts that the text alone cannot convey.

A few examples that come to mind from the Image Collection of Mihai Oroveanu from the first exhibition – EXPO_01_BUC_ARH_SP.PUBLIC – are connected to the contrast between the opulence and grandiosity of royal propaganda, which we see in buildings and in the international exhibitions that Romania took part in in the early 20th century, and the abject poverty in which most of the population lived back then. Or the contrast between the luxurious private mansions built in residential neighborhoods in northern Bucharest around the ’30s and ’40s for the wealthy classes and the clusters of apartment blocks built under national communism, which were to provide the working class with decent living conditions on the outskirts. Or the transformation of neighborhoods like Drumul Taberei from almost rural areas to neighborhoods able to house tens and then hundreds of thousands of people. We can also see such contrasts today just by walking down the streets of Bucharest.

I believe this kind of photographic documentation can give us a broader historical perspective to help us understand where the contrasts we see originate from, contrasts that, most of the time, are the result of long-term, complex social and historical processes and upheavals. To me this means being aware that being in the present does not happen in a vacuum but in a tight relationship with historical continuities and discontinuities that we either notice or we don’t. And photographic archives can be a playful and captivating way of (re)connecting to them.

[1] https://www.historia.ro/sectiune/general/articol/bucurestii-fotografului-nicolae-ionescu.

[2] In the first half of the 20th century, this building housed the offices and printing house of the newspaper Universul, and after the 1948 nationalization it became the headquarters of Întreprinderea Poligrafică [a printing company]. After 1953, it housed the newspaper Informația Bucureștiului and after the Revolution, Libertatea.

[3] Floch Jean-Marie, Visual Identities, Continuum Press, p. vi.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Raluca Țurcanașu

Raluca Țurcanașu is a former Account Manager who wanted to write. She's trying to blend visuals and words to tell compelling cultural stories. Raluca has been following image studies in Bucharest (C...

ra-luca.me/

Comments are closed here.