It is an ordinary summer evening and I am semi-consciously scrolling on Instagram. I often lie in bed tired and scroll down for a few minutes, allowing time to flow by. I don’t usually do anything interesting in those moments. But this time, I suddenly stop. I look at a picture and don’t understand what I’m seeing. It jolts me out of my numbness, my heartbeat quickens, but I don’t know if what I see on the screen is what’s really there, if it’s for real or I’m just projecting my feelings. LOVE LETTER TO…, says the announcement on Kilobase Bucharest’s page. It is a repost from Zina Gallery. I look at their page, too. Yes, I see it there as well, written in capital letters against a pink background. It is a gallery in Cluj. I live in Cluj… It takes me a few minutes to calm down and convince myself that it’s real: a love letter dedicated to the person you love and have just lost. And all of this right in Cluj, ffs. Is life messing with me? I don’t know how to react yet. I forward the post to my friends. They’re as confused as I was, what do they mean by love letter, what’s going to happen? I tell them that I figured from context that it’s an exhibition, and that is its title. But for just one moment I thought I had fallen down a rabbit hole where everything kept inside makes its way outside.

I wait for further posts about the event. Lo and behold, they are all letters: LOVE LETTER TO VEDA POPOVICI and LOVE LETTER TO MIHAI MIHALCEA. And then, LOVE LETTER TO IRINA BUJOR. Ah, I see, it’s a kind of artistic polyamory. Three solo shows at the same time, in the same place? Then, a new show is announced, CHANGE-EXCHANGE, with multiple artists: Jasmina Al-Qaisi, Apparatus 22, Georgiana Dobre & Kjersti Vetterstand. And then, another group show, TO CARVE A QUEER HOME, with Alex Bodea, Kilobase Bucharest, and the TRIUMF AMIRIA Manifesto.

When an exhibition is announced as a love letter, without even mentioning that it is an exhibition, without an explanation of the context and title, I feel comfortable similarly subverting the way people write about exhibitions and art. I have also titled my text a love letter, addressed to the whole event, TRIUMF AMIRIA: MUSEUM WORKINGS, which encompassed all the mini-exhibitions mentioned above. Seems like I ended up writing a poly love letter too. I can’t hide the personal perspective of this text. This is not an objective review: one of the artists is so dear to me, even after our separation, that an objective, neutral perspective, as one would expect of an art critic, without admiration or care for that person, cannot be expected to exist here. Some would say such a thing no longer exists, or wouldn’t expect it to exist. Still, it is not often that one mentions moments from one’s personal life in a review, especially if it’s connected to someone present in the show one is writing about. But I can’t speak in any other way – the personal is indeed political, as we learned with the second wave of feminism. I am convinced that my experiences – all of them, from my education and socialization to my identity in general, but also my deep and personal connection to this person – influence my view of the exhibition, are present with me when I step inside the gallery and when I write.

When I was invited to write about the exhibition, in addition to being very surprised – as I do not normally write art reviews in Romanian, though it is not that far from my field, as I also work as a theater critic – I laughed. I laughed because it really did seem life was messing with me, putting me in this position. Then I laughed again and agreed to do it, I said to myself, I’ll write them a queer review like none other. I feel weird. Guilty. I am a bit ashamed, now, when I see that I have already written almost a full introductory page in which my personal position takes the spotlight. Then I realize that is not something I should apologize for: queer art and the experience of queer people were – and still are – marginalized in so-called art history. What I am doing here is reclaiming the space, while also hijacking, queering mainstream discourse, like in the case of the mini-exhibitions curated as part of the project TRIUMF AMIRIA: The Museum of Queer Culture.

*

In the following paragraphs I will take the readers with me on a tour through the mini-exhibition rooms. Zina Gallery is a very intimate space, with four small rooms. I thought it was an excellent space for the event’s concept, rethinking the possibilities of museum-like exhibitions from queer perspectives, where multiple artists have been exhibited in solo or group shows. From one room to the next you can see and hear parts of the other works on display, which creates a dialogue between the different themes and perspectives on queerness proposed by the exhibited artists.

The first work that catches my attention is Jasmina Al-Qaisi’s audio installation a language of question marks. The work is a collage of various people answering one question: “How do you say queer in your language?” The current version, co-performed by Al-Qaisi and Raj Alexandru Udrea, is 53 minutes long, which doesn’t allow for a full listen during a visit, and such situations always put me off. I want to have the patience and chance to listen to it from beginning to end, then and there. Still, perhaps the installation was not conceived to be experienced like that. The repetitions in the text, the parts that are sung or read out in different ways, in different tones, in multiple voices, and often in comrade Raj’s sweet playful voice, give the whole exhibition an acoustic theme.

How does it feel like to lie on the floor in a narrow room, with drawings of handcuffed bodies (Veda Popovici), while you look beyond and see a man lying face-down on the ground in multiple photographs, in different landscapes (Mihai Mihalcea/Farid Fairuz) and hear the question being repeated in Al-Qaisi’s work: who are you? And indeed, who am I right now? I feel cut off from all the troubles created by the pandemic, from all the separations I am living through, from all the instances of inequality and injustice that I have experienced and witnessed in our post socialist capitalism. Here, I feel myself light. My torn body finds its place in this nest: I find myself in the landscape, I empathize with myself, like in a mirror, and my struggles are recognized here. And the friendly voices from the audio work guide me to a state of groundedness where I can accept the heavy feelings passing through me and where I see a queer opening within East-European / Balkan / Romanian / Transylvanian space and time.

Because I am writing about the exhibition, I was fortunate enough to have access to a language of question marks in full, and I could listen to it in privacy, in a hot bath, with a glass of dry red wine. Listening and relistening to this work inspired me to contribute my own answer to the question of what queer means to me in my own language. I very much like this concept of creating a glossary of explanations and reflections on the word queer from people from various spaces and contexts. The exhibition’s visitors could send the artist their contributions, and anyone who wants can still contribute to this work (send a voice message, regardless of length, to limbasemnelordeintrebare@protonmail.com), which therefore has the potential of accumulating hours of audio. I hope it will become a comprehensive, subjective, and queer dictionary. I recorded my own answer, which you can listen to here – you can hear a few drops of water, perhaps that is their way of answering.

*

When I entered the gallery, my ears were caught by Jasmina Al-Qaisi’s work, but my eyes drew me to the room on the right, which contained a series of highly decorative and colorful objects. I’m just a bird flying after anything shiny. So I immediately met the characters – Charmer Costel, ISGODB (IstrikeGoldonDailyBasis), Diamond Diamond Damian, and Seksi Adriana de România – that is, an installation by Irina Bujor titled TV ON ACID. Irony, humor, grotesquery, queer camp aesthetics, and a critique of mainstream capitalist culture are brought together in these installations. You laugh and fall in love with the characters at the same time. Four doll heads, remodeled and decorated with various objects, cut noses, eyes and lips dappled with yellow, with red stripes – a note of horror mixed with glitter, colored clothes, and small mice on two barrels, also dressed in shiny outfits; it is a kind of queer horror. If we think of showbiz, of reality TV, you distance yourself from these characters and see everything on a screen, you see a show – as the title says, this is TV on acid, the society of the spectacle in which we live. But, for me, this is more than distancing, horror, and laughter; I, for one, identify with these characters, I feel I am myself some kind of SpaceAngelGlitterTrash, constantly performing a game with my identity. A beautiful, sparkling, funny, and often collective game. Other times, because of the context we live in, it becomes an absurd, sly game.

Next to the dolls is a huge mask made of colored cloth, a collage, behind which you can hide from the TV on acid, from society, for just one second, and listen to the sound installation To teach gender openness in schools. The giant mask is a shield protecting the viewer while they listen to the sentence “to teach gender openness in schools” sung in an opera voice. It is a magical shield manifested as a safe space – at least for a few seconds or minutes, while you’re there.

Perhaps it is a magical shield that will manifest the recited message, who knows…

As I come out, I notice the photograph titled Self-Portrait with Amar-Amărât Objects. Bujor published a text in the book Kilobase Bucharest A-Z about the concept of amar-amărât, used when referring to objects that could never fit the definition of beauty, that contain flaws that are, however, charming, politically incorrect. Like the objects in the photograph: the head of a Black, racialized doll, a figurine of a porcelain seal, and an object reminiscent of an octopus and a vulva. Yes, that is how I feel too, amar-amărât (bitter/downcast), in the mirror of this photograph.

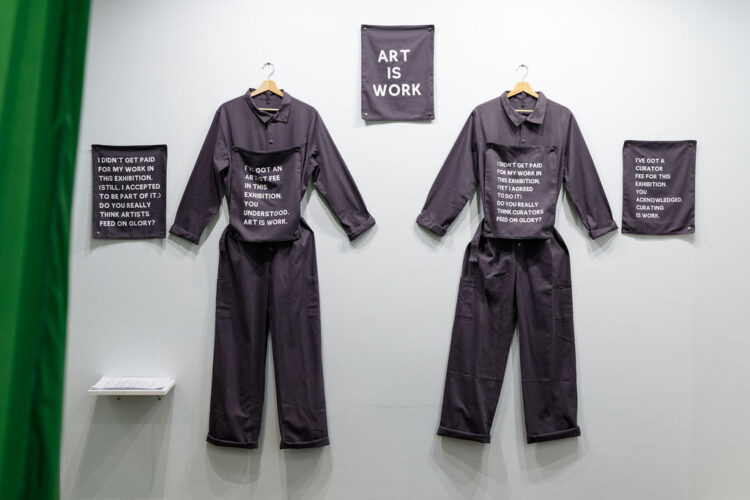

I return to the first room, where I came in, and find myself face to face with the overalls made by Apparatus 22. ART IS WORK is written in capital letters on one of the detachable pieces, the others being texts addressing whether the given artist/curator was paid for their work. The idea is that multiple such overalls will be distributed to artists and curators, who will wear the message according to the context they find themselves in, giving them the chance to start a discussion about artistic work as real work. This topic has become all the more urgent in the context of the pandemic, when many independent artists have lost their income and cultural and artistic work has not been classified as essential work. Of course, artistic work does not compare to hospital work or the work of bus drivers from the perspective of people’s immediate, urgent survival; still, the viewpoint that art is not essential work stems rather from capitalist thinking, which deems anything that produces profit and accumulates capital as important, essential even. I look forward to seeing how the project will evolve and where we will begin to see artists wearing futuristic overalls.

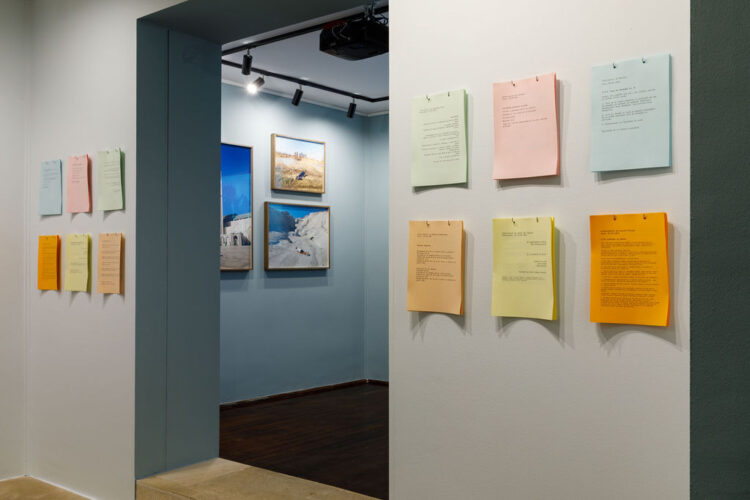

On the wall in front of the entrance are papers with texts in Romanian and English, part of collaborative and participatory works put together by Georgiana Dobre and Kjersti Vetterstad. The papers, which can be taken home, include contributions by Jakub Jan Ceglarz, Georgiana Dobre, Pernille Mercury Lindstad, Koyote Millar, Kjersti Vetterstad, and Synnøve Sizou G. Wtten. The texts are part of the project called The Book of Change, which will contain multiple sets of instructions inviting the viewers to deconstruct binary, heteronormative thinking about body and gender, as well as our position towards other beings and the environment. The instructions presented in the exhibition vary quite a lot: some resemble somatic grounding exercises, others are more playful, lyrical, or funny. I will leave you a short and very simple one here: “Mirroring mirror neurons: Invite a person to join you / Find a place for both of you to lie down / Close your eyes / Breathe steadily / For 5 minutes imagine you are the other person.” The exercise brings into focus a capacity for empathy, but in the context of the exhibition it seems to be more than that: it captures the queer game of whether you are capable to think and act like someone – be it someone you know or a stranger.

*

From the moment you enter the gallery, you can see a video installation through the door to the third room, where the works of Mihai Mihalcea/Farid Fairuz are displayed. We have, in fact, two videos – Afifarid (2011) and Lament (not Mecca, not Rome) – in which Farid Fairuz, artist Mihai Mihalcea’s Lebanese alter ego, intervenes in two different spaces: in a Bucharest mall and in Basel, during Art Basel. Fairuz’s figure is always adorned with hair and a thick black beard, imitating the stereotypical look of Arab men. Fairuz interacts with people in the mall at random and is very interested to see how they react, who smiles, what the children do when they see this fantastic character dance comically, talking nonsense, and dressed completely inadequately for this environment. In the Basel scene, we follow Fairuz’s path from the train station to Art Basel, during which he attempts to enter various luxury stores, but stops at the door, as if unable to go in. His choreographed movements start from Pina Bausch, highlighting the following question – and associated critique – related to the capitalist (art)world: who receives attention and financial support, where, and how?

I understand that from a postmodern perspective in which playing with identity has no limits, the character of Farid Fairuz is a deconstruction of the position of power in which the director of an institution (as Mihai Mihalcea was once the director of the National Dance Center in Bucharest, between 2005 and 2013) finds themselves – a position in which, despite the awards received and the approval of a specialized audience, he did not manage to pique the general Romanian public’s interest in the art of dance, nor to gather enough funds. The ridiculous character of Fairuz is a harsh critique of the conservative art world, of capitalist cultural production, of Romanian post socialist capitalism, of the ultraconservative religious environment, and of the general public’s expectations regarding art, as well as of the petty bourgeoisie that goes to malls and consumes mainstream art. As Mihalcea says in an interview, the character of Fairuz “announced the age of fake news that was to come.”[1]

Through Farid Fairuz, everything becomes ridiculous in a world where everything is already ridiculous. Fairuz draws attention to this fact, but there is also a political problem here that we cannot ignore in our current world, full of xenophobia, which has been steadily on the rise since the 2015 refugee crisis, a world that has remained racist, and, especially after 2001, under the influence of American culture, anti-Arab sentiment and islamophobia have made themselves known all over Europe. In spite of my understanding for comedy, humor, and postmodern play, I find it unacceptable to have this kind of comedy where the ridiculous factor doesn’t only touch on the critiqued system, but its source is connected to the representation of a culture we are not part of: this Lebanese character named Farid Fairuz, with his strange movements and strange look, who talks in quips and whose outfit is similar to the well-known “terrorist” character, is an exoticizing and frankly racist portrayal. I recall that movie with Louis de Funes that was constantly on TV in the ’90s, when I was a kid, The Mad Adventures of Rabbi Jacob, from 1973, whose humor was, for a lot of people, possibly functional, possible well-meaning for those times. Today, however, you can’t practice that kind of humor from decades ago. Mihai Mihalcea instrumentalized references to Lebanese culture and stereotypes about the Arab world for his own cause on the Romanian art scene.

Besides the two installations, various articles and interviews with Mihai Mihalcea/Farid Fairuz are pasted around the exhibition room, so that the viewer understands the context of this character’s creation, as well as why Mihalcea retired Farid Fairuz in 2019. He states, “the project reached its full absurd potential with the election of Donald Trump,”[2] a statement I wholeheartedly agree with, as I explained above. I think it is important that these works signed by Farid Fairuz be presented only with an explanation of their context, otherwise the intention of subverting the discourse around art can be missed, and all that remains in the spotlight is a grotesque character and a racist portrayal. But was this racist and problematic portrayal not always visible, even when the ridiculous situations it produced played an important role? I still wonder whether this character was ever legitimate in how he was performed, without losing sight of the important kind of critique produced through him.

The Farid Fairuz phenomenon has already taken up too much space in this review. I’ll go lie face-down on the dusty floor of my room for a sec, to get back to the partially funny, partially soothing and beautiful state that almost made me cry at the exhibition. Perhaps I’m ridiculous too. I think of the photos of the people Mihalcea interviewed in very different spaces. In the pictures you can see empty landscapes, with no other people around. Each place is present in its full strength and splendor, rich in various elements: boulders, churches, squares, urban nature (like the Văcărești Nature Park), with its grass and huge apartment buildings. In each picture, the artist is lying face-down. Funny, if we think of the famous photo of Yves Klein happily suspended in the air. But, at the same time, sincere and soothing in an Anthropocene/Capitalocene world, where we can no longer discern the borders between nature and culture, humans and other beings, and humans and environment so well anymore. The body almost becomes a landscape and, at the same time, it remains an exclamation mark in its anonymous loneliness, in the empty, pure landscapes.

*

The room containing Veda Popovici’s works has a completely different atmosphere from the previous ones. After a vulnerable body exhibited in vulnerable landscapes, we see a series of A5 pencil and watercolor works, in black and red, with handcuffed people overseen by an authoritarian figure, put on the ground, forced to kneel, isolated, trapped, all with their backs towards us, or fragmented images of hands and handcuffs, of muscles and different body parts, different expressions of human suffering. The exhibition’s curators did an excellent job displaying the works in each room, in how Jasmina Al-Qaisi’s installation is audible in the entire space, how the video draws you to the third room, and how the fragile drawings of fragile bodies seem almost hidden in the final room, the least exposed one in the gallery and also the smallest. The 25 A5 drawings are secured with two binder clips each and left to hang on one of the room’s longer walls. The pieces of paper are not straight, but undulating in various ways, from colors to graphite – the material perfectly captures the fragility of human bodies.

Besides the drawings of human figures are written lines of poetry, such as: “Where freedom is liberation / and nobody is trapped. / Where handcuffs are not justice / We have one question: / How much violence can we defend, / How much punishment can we dish out?” or “How much punishment can we dish out / that is beyond will? / And how much can we take? / It is powerlessness, / It is deprived power, / It is failed freedom. / In my dream / is it us / or is it them?” The drawings and poetry represent the songs of these bodies before unjust, punitive justice, before the prison industrial complex, which perpetuates forms of violence still endorsed by laws and states. The dream of the visionary from lucid, post-apocalyptic dreams appears in the middle of a pandemic, in a period marked by increasing authoritarianism / authoritarian power within the state. I hear Al-Qaisi repeating, Who are you? mixed with the voice of the bodies in Veda’s works: Who are they? Who are the kneeling figures? Who is here? The drawings and poems reject the punitive and violent world in which we live and which we often tacitly accept, through her songs of muscles, hands, backs, and knees crying out for a world without police, where justice is not violence, where there is no deprived power and powerlessness, demanding a liberated world. Even if we look at quite violent images, drawn in black and red, where the red constantly reminds us of blood, what happens in the room is liberating. The images and poems are horrifying and upsetting, they anger and provoke you, while at the same time awakening in you a kind of strange kindness when faced with so much fragility juxtaposed with so much coercion.

On the wall opposite these drawings is a poem, a march, in fact, titled just that, The March. The viewers may break the handcuffs and imagine themselves marching to a different world to the rhythm of the repetitive lyrics with an insurgent, liberating content. The poem makes your heart beat faster, and you can already feel the footsteps of the crowds, of the once-oppressed, the march of our bodies towards justice: “Watch our bodies / Rip apart and break / While We’re on our way / To tear down the world. / … / Watch our bodies / Cry and bleed out / While We’re on our way / To flood the world with the tears of Man. / … / Watch our bodies / Dance and love / While We’re on our way / To take back lost souls. / … / Watch our bodies / Collapse under exhaustion / While We’re on our way / To reclaim our labor. / … / To dismantle their fences. / … / To abolish property. / … / To reclaim our homes. / … / Watch our bodies / Get dragged on the pavement, bruised and wounded / While We’re on our way / To get justice.”

The anti-capitalist, anti-authoritarian, and anarchist messages in this song are in agreement with the artist’s political work: she is an activist for housing justice, an anti-racist and prison abolitionist feminist, and an engaged theorist. Still, it is a different experience to enter this room and experience political art than to just hear or read it. The atmosphere in the room is like that of a protest or direct action. Perhaps I am romanticizing the situation, as we are, in the end, in a commercial art gallery that has nothing to do with revolting. But for me that is what matters in art: to make you have strong feelings that you then take with you, that you can then return to or use in your everyday life. In the case of political art, it is clear that reading an insurgent song on a gallery wall is not the same thing as marching and demanding a better world, but until we are able to truly march, all we have left is our political, visionary, and revolutionary imagination, which inspires us to make progress towards this march, towards this insurgence. I really missed political art like Veda’s.

Another work is placed on the wall with the door. It is called Now-fall Handbook, and it teaches you how to fall. I am again pleasantly surprised by the fantastic display: next to the guide, through the door, you can see Mihai Mihalcea’s body face-down in a landscape, as if following the instructions. The Now-fall Handbook represents a somatic and performative practice that connects one of the two audio recordings with the artist’s voice and texts. The Story of the Fall appeared in the fourth issue of Bezna[3], in 2013, and was previously shown as a performative lecture in which the artist read the text live, together with the audience. Now we only have an audio, which we can listen to while sitting on the black cushions on the floor, while looking at the drawings of handcuffs. The voice speaks to us from the future, after the fall of current capitalist systems, and tells “the story of the end.”

The archived voice of the future visionary tells us how the Full-Fall came about following practices of Fall Initiation and the method of the Now-Fall Training System (NFTS) – a practice whose guidebook is on display by the door. As so many became tired of the ineffectiveness of strikes and protests, they began practicing Fall Initiation and non-participation in various mechanisms of the oppressive system. The text identifies fear as the obstacle preventing the systems’ fall. Through the somatic and performative practice of falling, we learn to accept fear and escape the traps of being afraid that hold us within the system. On an individual level, the fall reclaims the image of the epileptic losing consciousness for a few seconds, stopping in the most concrete sense, falling and disturbing everyday life for a short period of time. The epileptic falling in the dark without fear is the model for practicing falling into fear, the fall without the fear of fear. On a community level, falling is a spiritual practice, a community ritual for initiating the system’s fall, a form of political manifestation. On the level of systems, falling is a practice of political non-participation that gains revolutionary value when it reaches a certain level of implication that triggers the fall of all financial, state, etc. systems, eventually triggering the end, the apocalypse. But non-participation as a form of protest is in fact opposed to the idea of macho revolution, to the idea of a savior, a singular, masculine, strong Hero.

We live in the age of the Anthropocene/Capitalocene, caught in the lethal processes of the climate crisis, in the sixth mass extinction, and, starting last year, in a devastating pandemic. We are surrounded by death, and that is reflected in the industry of apocalyptic films and literature where, oftentimes, the world is destroyed and we all die. If the climate crisis continues to accelerate in our expanding capitalism, there is a chance that will be the case, that we’ll all die, at least the handcuffed, poor, and powerless ones. And for me, the most important idea of Veda Popovici’s performative reading is: if we are going to have an apocalypse, an end, let it be the apocalypse of the system and the end of the oppressive world of the present, not a total planetary apocalypse or the end of all beings living on this planet.

The practice of the falling is repeated in the other audio in the room, in the poem title In the Name of the Father – an Antiprayer, which appeared in the volume Arta revendicării – Antologie de poezie feministă, edited by Medeea Iancu.[4] The poem was recited during a performance where the artist repeatedly kneeled while reading it. And, in this poem, the kneeling, broken, and oppressed body of the woman devours and destroys the image of the patriarchal father, the idea of the master, empire, and capital: “in the name of the father. / in the name of the state. / in the name of empire. / in the name of capital. / in your name, masters. / I block myself. / I silence myself. / I cover myself. / I blind myself. / I devour myself. / and with me, you.” Besides falling, the poem also contains the idea of escaping your body by going inside-out, which, similar to the body without organs in the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, proposes performative liberation: “I have wiped the surface of the road / with my skin. / I lie on the side of the road / my face bashed in / and my torso broken. / how twisted must I lie for you to see me? / I will take myself and turn myself inside-out. / I open my mouth wide and grab this face / and push it down my throat. / then my whole head, with hair and ears. / then I shove my shoulders down my throat. / my ribs, / breasts, / and stomach. / I swallow my torso, / my legs. / and push them out, like giving birth. / like the doll. / which I am / which you are, he says.” This fragment is represented by the red A5 drawing displayed alone in the lower corner of the room’s right wall, next to the cushions and DVD player.

While we listen to the recordings and think about the apocalypse and protests… Who died? is written in white on a black flag placed in the corner of the room by the 25 drawings. The black flag, the anarchist flag, the black flag, the flag of mourning. If you are carrying a black flag at an event, a protest, or any anti-authoritarian collective, it often happens that your neighbors or passers-by ask you: who died? The common answer in such situations is to say that nobody died, the flag has a different meaning… But, in fact, in this context of prison violence, of the murderous system of capitalism, who died? Many have died and many will die in unjust circumstances. The questioning flag has multiple meanings on multiple levels: it is an ironic illustration of the situations where the political flag is mistaken for something else, but, more importantly, in the context it is displayed in, the wrong question becomes the most serious one. Through this détournement of détournement, we come to reflect, in the end, on mourning from a political, radical, and liberating perspective.

And so I leave the exhibition rooms with two questions in mind: Who are you? Who died? If we could answer these two questions clearly we could change the world, but change doesn’t come about so easily. Still, I leave with hope, inspiration, love, and indignation in my mind. I pass by the entrance, where I find the volume Bezna, the book Kilobase Bucharest A-Z, Alex Bodea’s drawing album, and the TRIUMF AMIRIA manifesto. I stop in the courtyard to grab a beer from the icebox, I stop next to Bodea’s drawings on a huge poster. This post-exhibition part was titled To Carve a Queer Home. Even this part points towards the future, towards a different kind of future, a kind and queer future, where we can build our own homes. Until then, we build queer dictionaries and safe(r) spaces, we demand that artistic work be recognized as work, we practice gender in non-oppressive ways, we lay claim to our presence in space, and we march, free ourselves, and demand a new world after the fall. Then, home…

[1] “Mihai Mihalcea – Moving Forward,” text by Irina Munteanu, Glamour Magazine, SS2021, p. 63.

[2] Ibid.

[3] The text can be read online here: http://bezzzna.blogspot.com/2013/06/bezna-4.html.

[4] The text can be read online, on the page of the project Literatură și Feminism: https://literaturasifeminism.wordpress.com/editura-pentru-literatura-feminista/.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Nóra Ugron

Nóra Ugron (b. 1994) works as a political justice activist as part of the Căși Sociale ACUM! movement and as an anti-species intersectional feminist. As an employed translator, editor and researche...

Comments are closed here.