Viva Arte Viva sets the tone for a celebrative and affirmative experience. Not only the overall title, but also the theme of the two curatorial exhibitions of Christine Macel pose the artist and his interior processes at the core of this year’s Biennial.

We encounter in the carefully constructed parcours of the exhibitions in Arsenale and Giardini artistic stations or universes which exhibit interior, sensorial, associative, visceral processes of what it means to ‘work artistically’.

The viewer encounters materiality, color, handcrafted products, tactile sensations and memories, even bricollage – so far away from the conceptually coded, hermetic, documentary and analytic experiences of previous Biennales, especially the last one curated by Okwui Enwezor, so dense in critical content.

Viva Arte Viva, on the contrary, is surprisingly apolitical to the point of confusing the viewer in search for references to the present with its tormented actuality. Abundant are quotes and qualities from a supposedly multicultural patrimony, which is regarded as a source for spirituality, renovation and healing for the European viewer. These workshop-situations or products are multiple in both exhibitions, from Ernesto Neto’s so called ayahuasca ceremony tent in the Arsenale (Sacred Place), the zen-performance of Lee Mingwei (When beauty visits), the traditional shadow theatre in the Chinese pavilion, to the colourful wool bubbles of Sheila Hicks’s and Cynthia Gutiérrez’s handcrafted sculptures in the Arsenale.

Interesting to observe is the recurrence of the theme of ritual across the Biennial, not only in the two curatorial exhibitions of Christine Macel, but also in national pavilions or singular works in which political, conceptual, futuristic or hybrid rituals are being specified and applied to the ground of shifting traditions of the present.

I had a few discussions during the opening days with artists and curators of whose awareness of ritual practice I found relevant for the expansion of performativity and processuality that we experience right now.

¡Únete! Join Us! – Jordi Colomer’s solo show curated by Manuel Segade for the Spanish Pavilion talks about a politically radical way to rethink social movement and action.

Marta Jecu: Which is the function of social ritual in your work?

Jordi Colomer: For me, the realization of this piece has been like walking on a path, meeting people and recording what happens during two months between us. The work starts with the fiction that there is a community of people which have no home and they need to meet sometimes, somewhere. Three women lead this movements and they invite people to gather both at the Parthenon in Greece and in Nashville, USA by reciting an invented spoken word poem. I work with symbolic elements here: first a changing flag made of many pieces of colors, whose pattern changes with the wind. There is also a uniform of some people of the group , which reminds of Pierre Cardin’s costume based on Mondrian. For the realization of this costume we went to a very old work uniform shop in Barcelona, and mixed the various designs encountered there. This Mondrian of invented colors defined the identity of this group which gathers sporadically in places that do not belong to anyone: parking lots for caravans in the wintertime, empty lots. Here they stop, tell a tale and take again the road. Another symbolic element is a transportable textile ceiling, carried by 4 people, which serves for developing further actions.

I was also looking at the ambiguity of belonging to or representing something. On the national pavilion façade we can read: Spain. But the first thing you see while entering is the flag of an invented country. How you decide and define your belonging to a group? Those rituals are improvised, temporary and based on a changing community – they represent a fluctuating architecture. Fascist movements had also a lot of rituals.

M.J.: Politics in general is based on ritual.

J.C.: At the time we have filmed in Nashville, I have seen the film of Robert Altman Nashville, where you can find plenty of symbolic political ritual elements. In my work the idea of scene is also very important: the marked place where someone addresses the word to a community.

M.J.: Time is also ambiguous in your work, as it evokes old, established symbols into the present. But the present itself is unclear, it has not historic reference, we are not sure where we situate ourselves on the timeline. Maybe this is characteristic of other videos of yours where different moments of time are mutually referenced.

J.C.: Yes, the film could be localized in the present or in a near future to come, in a moment in which people decide to leave homes and take the bikes and be permanently in movement and meet other people. This film was based on a Utopian architectural project that I have been long time thinking about and which is referencing Constant Nieuwenhuy’s anti-capitalist New Babylon (1959-74) [1] and Yona Friedman’s La Ville Spatiale [2]. These projects are similar as they imagine the city of a nomadic society. It is a city that is being built while people are moving and I was interested to imagine how this could work in the every-day reality. I did not try to recreate the architectural space imagined by these architects, but rather the dynamics of this space.

M.J.: Ritual is based on symbols, but in your work we have rituals where the symbols get dissolved. The actions seem symbolic, but they are actually not based on real symbols.

J.C.: Indeed! The symbols actually do not symbolize anything. We always need symbols but maybe these symbols – like the flag for example – are also capable of changing. In my work, the symbols are not fixed. Identifying the symbols by their content is possible, but the content is permanently susceptible to change.

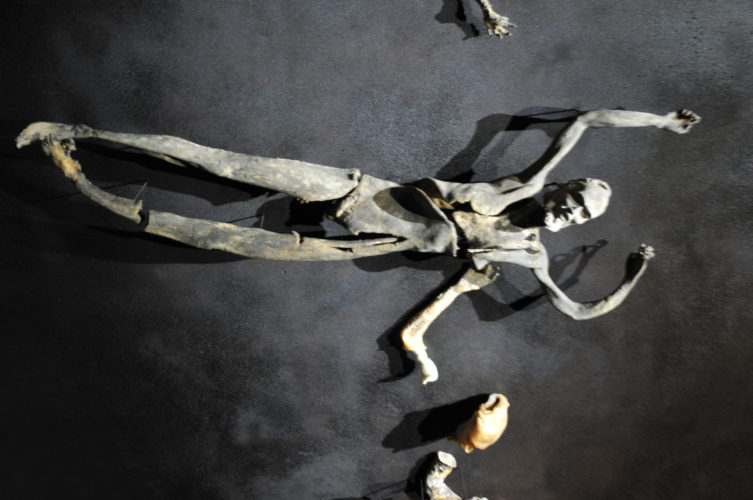

Il Mondo Magico, the group exhibition of Adelita Husni-Bey, Roberto Cuoghi and Giorgio Andreotta Calò curated by Ceclia Alemani has shown a totally different approach to ritual. Mystic references and retro-futurist tools of knowledge construct a search for what lies beyond visibility – as the curator expresses. The material body of Christ is recreated in the visceral darkness of an on-going laboratory (in Imitazione di Cristo by Roberto Cuoghi), a tarot workshop is used to explore the relationship between people and earth in an innovatory pedagogic practice (in the video of Adelita Husni-Bey) and in Senza Titolo – la fine del mondo Giorgio Andreotta Calò creates a world contained in itself where earth and sky reflect infinitely in each other. I have asked Cecilia Alemani in which way does she involve magic and ritual as a conceptual tool in her curatorial practice.

Cecilia Alemani: Ernesto de Martino (1908 –1965), an Italian anthropologist, studied in the 1940’s and 50’s contemporary rituals from the south of Italy. At that time the South practiced ancient rituals, was in deep poverty and was still not considered as making part of the high culture. De Martino was very fascinated by these rituals: myth and magic were for him a response to the existing crisis. He saw them as a means to reaffirm one’s presence in the world: not as a ritual of magic in an irrational way, but as a tool to reconstruct the world. I really liked this idea and it’s positive message.

M.J.: How do these themes relate to your previous curatorial work?

C.A.: I have been studying George Bataille and got to know de Martino through him. Roberto Cuoghi’s work Imitation of Christ is an open factory of figures of Christ. He wanted to show the uncertainty surrounding the physical appearance of Christ and the infinite repetition of this representation by setting up a factory of a unique mold with various materials which are organic, deteriorate in time and generate a life of their own. The process is completely uncontrollable by the artist: nature and spirituality take over and the end result is beneath the artist’s control. He uses a traditional, archaic Italian iconography with contemporary, futuristic techniques. As de Martino says: Magic is a way of reading the present. This show is about using magic, imagination and ritual to reconstruct a broken reality.

iyEye of Benin- Comparing Views on Rituals, curated by Paolo Rosso with Stephan Köhler and Georges Adéagbo, reunites five anthropological videos filmed by Achille Mauri in Benin, juxtaposed with recent video work of following Beninese artists: Ishola Akpo, Dimitri Fagbohoun, Pélagie Gbaguidi, Ines Johnson-Spain, Thierry Oussou, Totché, Séraphin Zounyekpe. The installation explores contemporary possibilities of situating the ritual, in which personal, quotidian, multiple definitions of tradition and cultural enacting, defy the dogmatic use of the term. The video collection is moreover framed through the installation work of Georges Adéagbo, which constructs meaning through associative cumulation of objects of material culture. His personally filtered exploration of history and cultural tradition assembles – in a performative ritual – a universe of images, texts and content. The following discussion was held in Venice with Stephan Köhler, Georges Adéagbo’s curator, producer and collaborator.

M.J.: Why rituals for contemporaneity?

S.K.: In order to create spaces for oneself. In a market dominated world with a lot of advertisement rituals are a way to come back to oneself and to one’s own rhythm. The rituals bring about the question to what one is destined, what one wants to do in his life. Ritual is connected to a question of identity. I do not see ritual connected to religion. There is a difference between ritual and liturgy. The latter is a sequence of actions that one does, formal actions, where you do not need to be necessarily involved. Ritual is actually the opposite. In our collection of film we have here a film by Totchè, where he develops his own ritual. The film of Thierry Oussou, ‘Unite’ contains actions like swing that connect fabrics on a material level but stage it also as symbolic actions that connect people. In many videos rituals are appropriated into the quotidian life. Here rituals are treated like ‘objects trouvés‘. We can actual speak about ‘ritual trouvé‘.

Generally speaking we have tried to find films which are not necessarily narrative. The film of Pelagie Gbaguidi (living in Brussels), The Missing Words shows her staying in a Muenchen museum’s storage room of African art. She wears a ’White man’s’ mask, playing the role of the discoverer in the museum’s archive. The film of Ines Johnson-Spain (living in Berlin) shows in Madjit a gay barber that describes how he is spiritually embedded into his voodoo community, instead of being marginalized. In her other film Avoir e Etre Ines Johnson-Spain discusses psychiatry in West Africa, as a function delivered by the family due to other social and temporal rituals of development of familiar relations than in the West. Seraphin Zounyekpe, works also on ‘rital trouvés’ – daily rituals on the market.

M.J.:This is a beautiful concept and fits the contemporary way to assume tradition and historically based rituals.

S.K.: Yes, by affirming a ritual it becomes real. We need to see, define and declare actions as rituals. Ritual has been always there, but by defining certain actions as rituals, they become that – same as Duchamp’s ready-mades become art by declaring them as such.

M.J.: These are form of appropriating rituals.

S.K.: Yes, whereas actions are framed in a certain way and shift to another level of significance.

M.J.: Which do you see is the leading thread between all these rituals that are presented in this show? Is it the self-definition process that you were mentioning earlier?

S.K.: Yes exactly. The question is how do you navigate? One talks to himself, one thinks about himself? One builds relations to close people, to the society and needs to follow how do one fully positions himself for a best scenario, for a win-win situation. Rituals can solve conflict before these become brutal.

M.J.:This is a therapeutic ritual function.

S.K.: Yes it is present in the film of Seraphin Zounyekpe as the call of the ancestor, which are all coming to find resolution of a fight in the family.

M.J.:How did you conceive the object-video relation in this curated exhibition?

S.K.: George considers his installations story-boards for films. Image and text are joined by associations, which construct a story in visual term, developing a narration. When he composes these installations he has a scenario in mind, where every object is part of it.

We were having a parallel event connected to the exhibition: a conference in the framework of Art and Neuroscience in dialogue organized by Elena Agudio. Here together with artists and scientists we tried to see how does the brain react to ‘miracle’. We talked about George’s work and his way to find objects in connection with others by association. But we also talked about his capacity to find aspects in quotidian objects, which permits him to see these objects as metaphors.

M.J.: There is also a ritualistic component in the way in which Adeagbo sets objects in space. His installations seem to be the result of a ritual action developed in that space.

S.K.: It is very interesting to watch George when he mounts the show. He recognises fields of energy between the objects and according to them places the objects very fast – as if he knew their position before, like following an inner map.

In this project, he has made the first time an installation around videos. This is an inter-medial project and in his work there is a strong curatorial aspect.

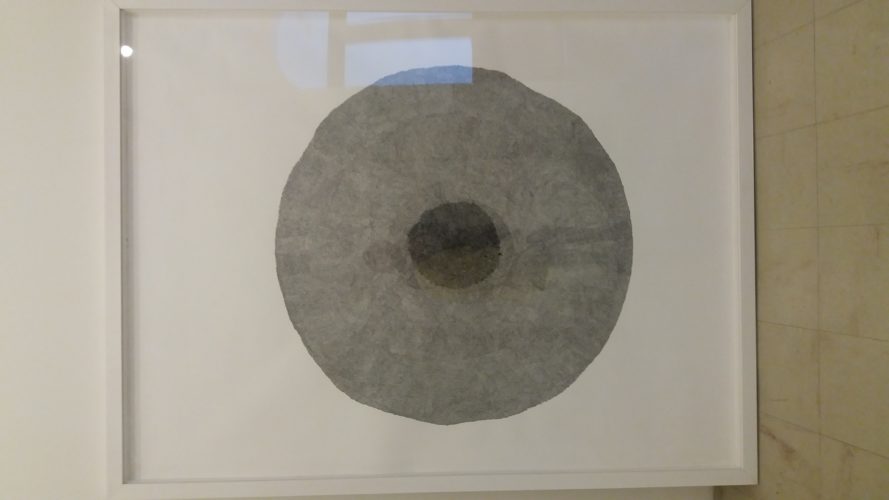

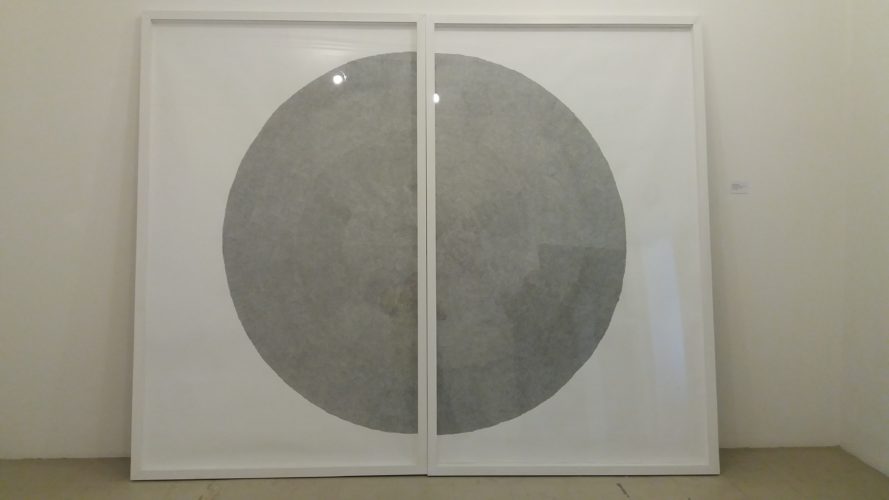

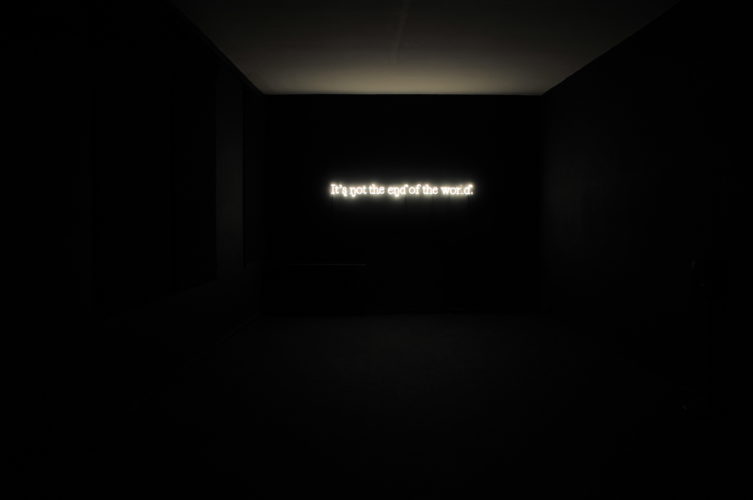

Dana Whabira shares in the following discussion, intertwined personal and historical preoccupations which form her collection of three works presented at the Venice Biennial in the Pavilion of Zimbabwe. Black Sunlight (a light sculpture and a sound piece), Circles of Uncertainty (a series of drawings), Suspended in Animation (a space filling army of sculptures), explore novel ways of rethinking (material, transnational, physical, liminal, imaginary) borders embedded in language, identity, cartography and geography.

D.W.: Circles of Uncertainty are an ongoing series of works on paper that map memory and migration. The title is taken from a procedure in flight navigation when a pilot is unsure about the aircraft’s co-ordinates and radius around the estimated position. Circles of Uncertainty (4), (5) and (6) lean to my own journeys between Zimbabwe and the United Kingdom. My drawing line creates a space devoid of geographical co-ordinates or landmarks that highlights the indeterminacy and dislocation inherent in migration. Taking as a point of departure the flight of my father into political exile from colonial Rhodesia to England, I meditate on the disorientating experience of being unanchored and displaced and how it felt to return into post-independent Zimbabwe. The resulting spiral in my drawing reflects an ever increasing circling in search of belonging, identity and stability; It is search for what has been lost – dignity, history, culture, and country. My drawing process communicates the constant feeling of being the outsider, who inhabits paradoxical sites of identification and alienation – both in the homeland and in the host country.

My intention with this work was most of all to bring about a form of mapping and anchoring of personal meaning into territory. I see this work also as a meditative journey. Through the drawing process in which I sat on the floor, I was trying to connect physically and achieve a connection with the earth where I was, in Zimbabwe. It is a repetitive and interiorised act and it is on some level quite spiritual.

The neon light statement composed of the sentence “It’s not the end of the world” in the installation Black Sunlight, is written in Shona language. The alphabet Shona was proposed by an English colonial linguist in order to unify the existing languages into this standard Shona. This is the most common language spoken today, but this forced and abusive introduction of this new language during colonial rule created a rapture of national identity. This piece is therefore referring the violence of cultural translation. In the installation Black Sunlight I also make reference to the cult novel ‘Black Sunlight’ by the iconic Zimbabwean writer Dambudzo Marechera. The book is written in a stream of consciousness narrative and it is not located in any time or space but explores the meaning of power, the role of institutions, ideology, by following an anarchist group who’s revolution nevertheless fails. I involve this story in relation to the formation of nationhood through language in relation to my culture. The sound piece accompanying this installation is composed of two sources extracted from lessons in the Shona language by a catholic reverend, which deliberately mistranslates the identity and philosophy of the Zimbabwean culture refered.

The three works that I present explore an alien subjectivity. Suspended in Animation (made in 2012) follows social alienation within labour, so it connects to the environment of migration and the crisis of labour. Who are we and how did we become alienated from each other? We find ourselves alienated from the tools we use, from the products we create in the late capitalism we live in. Where are we actually situated in this historic era?

Another body of work which explores historic archive and knowledge transmission through plunging into the self, is the Romanian pavilion which stood out for the accuracy of the display and the classicity of its curatorial approach. The two-fold project was constituted of the show in Romania’s pavilion in Giardini and the exhibition at the Romanian Cultural Institute. Magda Radu, the curator, explores the work of Geta Brătescu (born 1926), as a journey through her present creation in relation to ideas developped in a century long career. The core of this exhibition – the atelier as a space of feminine subjectivity, intimacy and mediatation – is a space of manifestation of the body, but also a space of continuous and audacious innovation, as show her recent stunning collage works. In this following dialogue Magda Radu describes her curatorial display solutions, marked by structure and limpidity, as resulting from thematic poles of the artists’ own sensible universe of thought.

M.R.: I have guided my curatorial work according to Geta Brătescu’s own vast artistic creation: she is a very versatile artist working in different media and also writing. Reading her text you get new keys of lecture on her work and get to know her vast cultural knowledge. So I wanted to present the complexity of her work and to reflect on the feminine subjectivity that she explores according to different reference characters for her and scaled on her own body. The exhibition is meant to be very intimate, without spectacular mechanisms of display.

M.J.: At the same time the exhibition steps out of a personal register and inscribes itself in a typology of museologic display.

M.R.: I wanted to stay as close as possible to the way in which Geta Brătescu herself presented her work in time, without forcing spectacular or cutting edge display tricks and solutions. I needed also a visible and structuring parcours which could display coherently her different types of works and connect them in a clear way. ‘The atelier’ became a theme of mental exploration as well as a reflection on feminity. I included in this exhibition also objects which she has inherited from her family (The glasses of my father, Selfportrait in a mirror or a weight from her father’s pharmacy), which are also important presences in her atelier. All these reference objects seem to have for her a magic value. Personal memories from World War II and Bertold Brecht’s Mutter Courage along with Faust also built up this universe. There is also a performative and serial quality in the exhibition. Drawing is like a compulsive, automatic act where the artists’ body is engaged in the act of ‘doing art’. The recent video, Linia, filmed at her desire by Stefan Sava and projected at the entrance of the exhibition, introduces you into a quotidian moment of her drawing work, where her hands draw a simple line. In the second part of this project, the exhibition at the Romanian Cultural Institute, we had the video Hands, which is filmed in the 1970s and which captures a moment of anxiety before starting ‘doing art’. I didn’t take into consideration the theme of the biennial when thinking the exhibition. There is a preponderance of the atelier as theme in the entire biennial, but I didn’t intend to import the atelier of Geta Brătescu into the exhibition as a physical working studio. We imagined the atelier, on the contrary, as a meta-artistic entity, which functions on plural levels.

For Geta creativity is feminine. When she interprets the texts of Goethe’s Faust, taking into considerations also texts from Jung, she talks about ‘mume’ – as creators of forms. She thinks about what it means to be a creative woman. I didn’t want to present an exhaustive or chronologic exhibition, but rather an excavation into her universe of perception. She is interested herself more into what she is working on in the present moment, and she had the idea of presenting her recent collages on a big wall. This wall, which centers the entire exhibition, shows her as an active spirit, anchored into contemporaneity, preventing the perspective of a retrospective show.

M.J.: How did you construct the show between the two exhibition spaces: the pavilion in Giardini and the space at the Romanian Cultural Center?

M.R.: I intended to use the space at The Romanian Cultural institute as a point of information, where one could consult additional material on her work. The exhibition includes issues of the magazine Secolul 20 where she collaborated, editions of Faust published in the 1980s with her illustrations, her travel books in Italy and catalogs published on her. But I extended this material with works which reveal her process of work: for example with her own artistic research connected to her series of lithographs Medea. We have showed also drawings done by her with closed eyes, which also are an exploration of processes of interiority through mental images.

[1] Constant imagined New Babylon with the goal of creating alternative and play-based life experiences, called ‘situations’. The idea, which was transmitted by Constant*s paintings, sketches, texts and architectural models was later adopted by the Situationists and affirmed the belief that the use of space and architecture would transform the daily life

[2] Yona Friedman imagined a mobile architecture over the city of New York, which would permit self generative building strategies, where the inhabitants could design their own living segments according to their taste. The city suspended over new York would not make use of extra space.

POSTED BY

Marta Jecu

Marta Jecu is researcher at the CICANT, Universidade Lusofona, Lisbon and freelance curator. She has published in magazines like: E-Flux, Kaleidoscope, Berlin Art Link, Idea Art+Society, Journal of Cu...

www.martajecu.com

Comments are closed here.