In 2022, Gaep continued a series of online exhibitions it has started on its website in 2020 with Resilience Test. This year’s project, named Time Lines, brought together three exhibitions focused on the temporality embedded in drawings practices and beyond. Curated by Mihaela Chiriac, Time Lines reopened Gaep’s Viewing Rooms between April 18 and August 21, when, for six weeks dedicated to each artist, recent works by Ignacio Uriarte, Raluca Popa and Răzvan Anton created space for thoughts about work, school and memory.

IGNACIO URIARTE

“Impatience must be exhausted in a series of meaningless acts.”

Ignacio Uriarte’s minimalist works stem from a background as a Business Administration graduate who only became attached to office jobs after quitting them for good, which is also when he began to draw inspiration from them for his art. Born in 1972, Uriarte studied in Madrid, Mannheim and Guadalajara. Along the way, he garnered experience in large companies, while also becoming increasingly interested in conceptual and self-referential art. “Uriarte would soon realize how interested he was in the fact that what was said and how it was said could be the same”, notes critic Javier Hontoria, who also mentions that the artist was drawn to works such as Schema (March 1966) by Dan Graham and Card File by Robert Morris. In 2003, he ended a life stage with a resignation and, that same year, he produced his first artwork, Envelope – a windowed envelope, open at the seams, that reverses convention: the inside is entirely visible, while the window, superimposed on white background, no longer reveals any information.

The 9-to-5 life, as he had discovered by living it, was a long series of repetitive acts that accompanied the slow passage of time, a time they added meaning to with all the help that stationery could provide. When he closed the office door determined to never return, Uriarte didn’t leave the tools behind. Pens, papers, paper clips, excels, typewriters became his work instruments in a new paradigm. Instead of being the accessories they are in the corporate environment, they now come to the fore, to tell the story of the universe they come from.

As an artist, Uriarte prefers geometry and austerity, repetitions and systematizations, combining the playfulness of experimentation with a bureaucratic sense or order. Automatisms, mechanical movements, tics of inefficiency are constant sources of inspiration, as seen in Monochromes without Ink, from 2008, made by scratching the surface of cotton paper with an empty pen. The boredom of office work, the dozens of ways in which we roll time and in which it rolls in us (in which we kill time) can also be found in Blocs, a series of works in which the artist simply tears pages from a notebook, in Archivadores en Archivo, a sequence of images of file shelves being filled and emptied seemingly endlessly, or in Papierballfall, a loop video showing paper balls landing in a trash can.

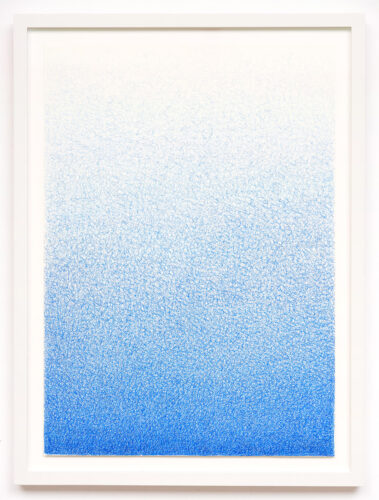

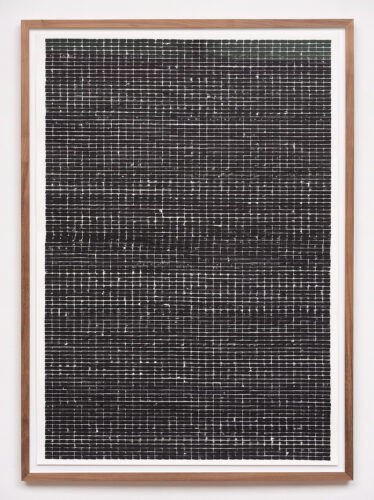

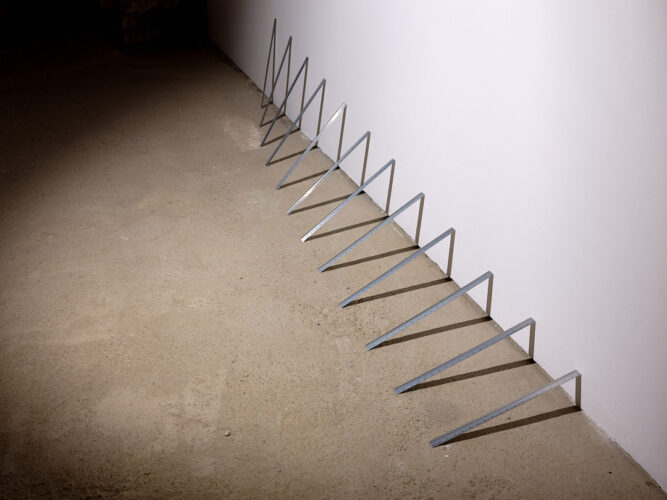

We also find this nod to the things you do in order not to do what is expected of you on the Gaep website. In Blue Scribble Grading, the artist lets the pen roam over the surface of the paper without lifting it. The sheet becomes a cell in which the streak of color paves its frustrating way, unable to leave the frame. The selection of six works in Time Lines spans the years 2016-2022 and, except for one installation with rulers leaning against the wall, it focuses on drawings on paper. Referring to this kind of dead time, curator Mihaela Chiriac points out, Uriarte devised a sort of “manual automation”. The “counter-efficiency” also insinuates itself in Black Stamped Monochrome, “a print – but one made manually, by stamping with the tip of a marker rows and rows of small black rectangles, until the page is filled, save for a white border that has been kept as clean and straight as possible during this process.”

It is worth noting that Uriarte, who lived through the era of floppy disks, chose to work exclusively with the visual configurations of the office world of his youth. “Because those experiences occurred in a particular decade, from 1992 to 2003, my work is being increasingly archaeological”, Uriarte said in a conversation with the critic and curator Franz Thalmair. “I have put on the corset, so to speak, that I cannot leave the four walls of the office from which I came. Because I cannot go wide, however, I go deep.” What comes out of his Berlin studio has an impact through accumulation, that of the objects and gestures in one work, as well as that of all his works. Taken as a whole, his practice seems like an inexhaustible exercise in creativity whose aim is to deliver chapters from the biography of a life he did not wish to have. It’s hard to reproach him with predictability, precisely because he juggles elements which are so familiar and so actual still. As long as too many office towers continue to rise compared to how few dream of working in them, Uriarte has something powerful to convey, even with his way of repositioning elements without enforcing a message. “My works are often empty containers – as open as Kafka’s novels,” he also said to Thalmair. “You can bring a great many things yourself and interpret them differently depending on your daily constitution.”

RALUCA POPA

“I would like to distance myself from saying something in a didactic way, because the material itself comes from that area.”

The manual aspect of work, iterations, finding meaning in the loss or relativization of meaning are also present in Raluca Popa’s recent Works (Scale 1:2). The Berlin-based artist started from a collection of 197 middle-school and high-school test papers (from 1992, when she entered 6th grade, until 1998), which she has kept and carried with her over the years, including in 2010, in London, where she studied for a master’s degree in Fine Art. “I think I’ve been meaning to do something with them for 14 years,” she says. Popa first sifted through them in 2013, when she published three facsimiles of civic culture test papers in Idea magazine. “They seemed one and the same material, and I was struck by this identification of one with the other,” she says, recalling the sense of disorientation she had upon rereading them. She wanted to shed light on these aspects, without any intention of irony. “I then decided to publish three documents which, although dealing with different themes, seemed to be the same thing. And I began to reflect on the kind of information that is being fed to us, on our inability to judge specifically in different situations and not generalize, while these images seemed to signal a gross generalization of the topics being discussed.”

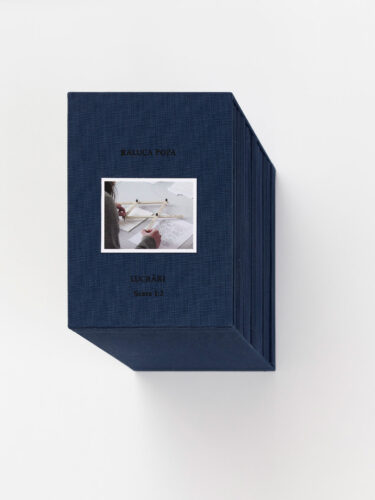

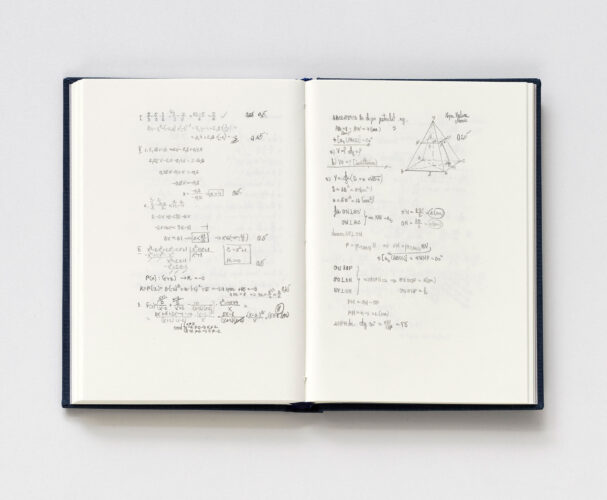

For Works (Scale 1:2), the artist opened each one of her test papers, that source of anxiety and pride, for an actual measuring of the way in which knowledge was evaluated in the Romanian educational system of the 1990s. The outcome is a navy blue slipcase of 15.5 x 11 x 12.8 cm, containing 13 casebound books of different thickness, each bearing the name of a school subject: Romanian, Mathematics, French, English, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, Geography, History, Latin, Music, Religion, and Civic Culture, respectively. A photograph on the cover offers an insight into the work process. The image shows Popa maneuvering a pantograph, an instrument used for technical drawings, which enables the manual replication of shapes to a reduced or enlarged scale. The pantograph was once used to draw maps, to represent spaces. Using it in this context was like mapping the space of the test papers. “I tried not to think only of the content, of what I wrote years ago and am re-reading now, but to think about them as a whole, as a sculptural object,” she says. “They occupy a place in the physical space, and this instrument, I believe, emphasizes especially that physicality they have.”

Popa first used the pantograph in 2019 for How to Disappear, her first solo exhibition at Gaep, when she zoomed in and out of two test papers on human activity and the anatomy of the eye. She thought of them as having resolution, like film frames which, through copying, through repeated and clumsy resizing, become more and more blurred and incomprehensible. She liked the fact that the pantograph allowed for some distance – she was copying the works, but not with her own hand, which had written those lines, but by handling the arms of an instrument.

“The artist duplicated the motions of her handwriting while choosing to decrease its size by half”, explains Mihaela Chiriac in her curatorial text for Works (Scale 1:2), first shown in the online exhibition Time Lines. “Throughout this tedious and time-consuming operation the pantograph facilitates replication as exact as it’s manually possible, while at the same time allowing Popa to somewhat distance herself from her previous authorship, and, furthermore, to level and condense her own and the teacher’s authorship into one single monochrome construction of miniature size, written – or drawn – with graphite on paper.”

It is, the artist notes, a bit like the phrase she so often heard during her childhood: “Measure your words!”. In a way, she actually measured the words and the information written in the pages. It was quite serendipitous that, in a year of two-day long flare-ups on Facebook, her work was posted online at about the same time as the feed sizzled with a heated discussion about the point of flower crowns for pupils in 2022, about how we regard top graders in Romania and, along with them, the notion of a successful education. People who, like the artist herself, used to delight their parents with prizes at the end of the school year in the ‘90s flooded the social network with questions related to the use of the ultimate validation one found in straight A‘s. Superimposed on the many opinions for and against wreaths, Raluca Popa’s test papers, neatly packed in their linen case, summarized as if in a quiet question mark our relationship to performance, to a culture based on competition and on conveying the impression of being an all-rounder and, especially, to the fact that many of us have no idea what to do with the legacy of having been top of the class.

“By decreasing the size of the writing, Popa is literally performing its reductio ad absurdum”, Chiriac notes. “By resizing and hence reducing the volume that these papers take in space, the artist is hinting at the devaluation in time of the education she successfully received within that specific framework, or at the very least at her re-evaluation of it.”

Popa avoids offering a key to the interpretation of her work. “I think we should give ourselves more time to judge these things”, she told me, adding that she tries not to think about school when working with the tests. In her practice, which often involves working with pre-existing material, like family archives, she does not like to handle anything which is very obvious. As for Works (Scale 1:2), she is on the guard against sticking a message to an image of the past which, even for her, is in an ongoing developing process. “I think that’s what I’m more interested in – working with more nuanced or vague, unstable areas,” she says. “The work somehow remains open for me as well, because I intend to use this material again. It is important in my work to give myself these possibilities, to test different methodologies and meanings, in a non-authoritative way, and if the public reads the work in different ways, it means that I managed to take the material out of its conventional context, that I set something in motion.”

RĂZVAN ANTON

“If you know what you’re looking at or how exactly you’re looking, you’re likely to find the appropriate manner to move forward.”

The work with pre-existing material also dominates Răzvan Anton’s practice, since his life crossed path with the Minerva Press Photo Archive. Starting with 2016, the artist from Cluj-Napoca has been working almost exclusively with found images and archives. Rediscovered by artist Miklósi Dénes, Anton’s colleague at the University of Art and Design, where they both teach Graphics, the archive included negatives of the Cluj newspapers Igazság and Făclia. More precisely, over 30,000 images, most of them never published, which capture the public life in the county between 1960 and 1990, and sometimes the private life as well – the few photojournalists of the publications slipped experimental or personal frames onto the film scraps. Dénes and Anton immediately understood the value of the archive and, helped by volunteers, started a deeply collective process of digital archiving and dissemination through a website available in Romanian, Hungarian and English. Through his work as an archivist, Anton discovered images from an era to which he could relate and which also concerned him, a Cluj from very before his birth. “It’s as if a different city got built between the ’60s and the ’80s – the working-class neighborhoods, the industrial area –, it was just a changed city.”

Working with Minerva led to some more obvious connections between the things he was doing as an artist and the stakes of those gestures, and, hence, to the reorientation of a practice that had been focused on drawing. “You’re still reproducing some gestures you practiced in school,” he says, speaking of the years of self-searching after graduation. “And you try to figure out what art is about or what its subject is. Often times, you have the feeling that the subject is right there, in the practice. I found out quite late what I really wanted to work with. There are artists who quickly realize that the practice is elsewhere, they connect more quickly to society – where to act, what one does as an artist. It was only then, [in 2014-15], that I understood what I could work with, and it was also then that I gave up the logic of a studio practice, of inertial work. I couldn’t understand artists who said that this inertial practice does not exist, that it is a trap. But I think I understood then the meaning of not working without a horizon, without a subject.”

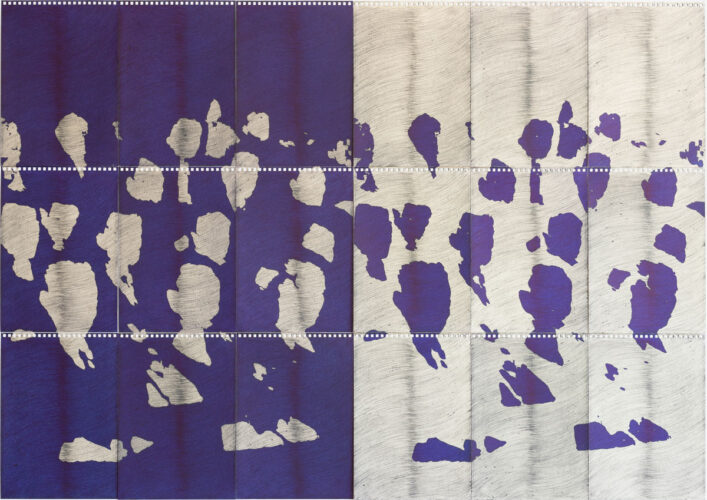

Anton went from drawing freely from selected archival images to experimenting with heliographs. Keeping his archivist’s garb, he started with two categories of images, the ones he had seen most often: people at work and political meetings. “I drew and printed those first, in the logic of a technique. Then I started looking for a procedural logic in this way of printing. I realized that the most important part is looking at the images, not working with them or reproducing them.” The sun entered the story quite quickly. Seeing that blue pens are photosensitive, Anton began to use them as a kind of emulsion. To print an image, he hatches several drawing sheets with a bunch of blue ballpoint pens, juxtaposes transparent masks to them (fragments of the negative of the chosen photograph), and sticks them to the windows of the building where his studio is. The exposure lasts several weeks or months, depending on the season. The outcome, something between drawing and photography, an image broken into several sheets, is reminiscent of both an inkwell and Instagram grids.

“Anton uses existing photographs as a template in order to, somewhat paradoxically, excavate a hidden, perhaps wider meaning from their surface through the heliographic process”, Chiriac notes. “Resorting to this radically slow proto-photographic technique, which requires months of natural processing (waiting for a satisfying result) and which references a time perception pertaining to the pre-industrial age, certainly offers, by contrast, a comment on the current modes and speeds of capitalist production.“

Seeing four of his heliographs pinned on the wall of his studio on a hot August day was also an encounter with the lyricism of their fragility. They are works that the wind can easily blow away and that the light continues to transform as our gaze fills them with the meaning of a moment in time. For Anton, who seems to take delight in this playful and gentle collaboration with the sun (he also tried developing with a magnifying glass), it is a suitable process for these images, but one which he must be prepared to give up. “I’m not sure I’ll work with it forever,” he says. “A technique is something objective, like a recipe you use for any image, but a process or a procedural practice means that you develop something in relation to a subject, that you work with something which is related to that subject.”

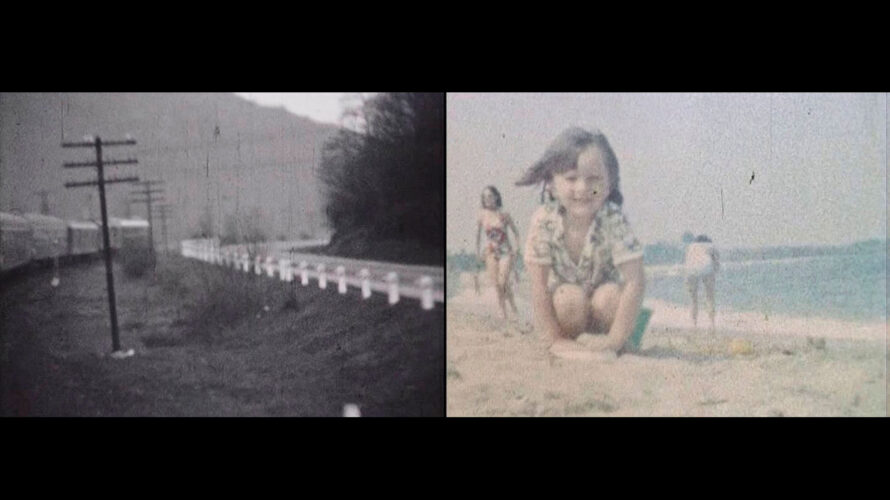

Recently, Anton has moved his focus from Minerva to the family’s 8mm film collection, which he digitized in 2015. The artist’s father, an electrical engineer, got his camera when he was around 20. He used it almost exclusively to document his family life and moments with loved ones, without any artistic pretence, but careful with framing, meticulous with exposure. This time, Anton no longer watched the films with the eyes of a son who is curious to discover his past, but rather from a distance, disconnecting himself from the personal, which he doesn’t want to exploit, and looking, in a way, for what family films have in common, by using what he calls the lens of an archivist: “I’m interested in finding what’s common to what’s private. I think that’s the subject. Like a pattern.” Thus, Time Lines includes the video work Archival Study (Places and Portraits), a split screen that presents looping footage from the ’70s and ’80s, cut and edited by the artist following two categories: places and portraits. The durations of the two montages are different, so the left-right image pairs are never the same. The mixed experience of making it – “It’s not a nostalgic look at the family collection, but I can’t say it’s a completely non-nostalgic look”, the artist admits – is also echoed in the viewing experience.

Anton says he does not regard photography in an artistic sense, but rather in an anthropological one – he is interested in the place it occupies in our world, the place it occupied in the world 30or 40 years ago. And he hopes his role as an artist, which he aspires to be a socially active one, will also be related to this – to putting together images that form a landscape of the past: “Now I know that I am working with memory or the idea of memory.”

***

Presenting three different perspectives on drawing, the Time Lines project tells the stories of three artists aged between 42 and 50 for whom the current way of seeing and practicing their art is the result of long searches. They all work with something detached from their past without imposing a first person, without attaching either definitions or verdicts, and perhaps it is precisely this detachment that creates space for empathy, helping to avoid extrasensitivity. Rather, inviting to another twist of the prism.

POSTED BY

Gabriela Pițurlea

Gabriela Pițurlea is a freelance writer and editor. She studied Journalism and Advertising, and started by working as a reporter for Esquire Romania and DoR. She is the co-founder of SUB25.ro....

Comments are closed here.