The isolation megadose that many of us received this spring, when countries around the world went under lockdown, changed in many ways how we relate to our bodies.

Most social interactions moved online – we got used to seeing our closest friends and colleagues on screens, and even when there is nothing but air between us, touching someone seems almost forbidden. Forced to walk on the spot in our homes, we had to contemplate our bodies, often ignored or forgotten in the hurricane of things that seem more pressing than our simple being. We ran against our bodies’ needs, their limits, their nostalgia and their aspirations. We dressed them differently, we fed them differently. We adapted them to a world where going to the theater, to the movies or to the museum is an encounter for which only the mind needs to travel.

The body, as well as art’s transition to the screen, are also what Resilience Test, the first series of online exhibitions presented by Gaep and co-financed by the Romanian Ministry of Culture, is about. Featuring three artists from different generations and countries – Marilena Preda Sânc, Vlatka Horvat and Ištvan Išt Huzjan – for three weeks each, the project curated by Tevž Logar showcases practices that are “connected by their shared interest in re-examining resilience and the sociopolitical role of the body”, and it does so at a time when more and more art galleries are starting to use viewing rooms as a way of keeping their audiences close. If until recently art fairs used to serve the purpose of connecting them to a wider public, the art world is now talking about a shift to the online.

“The art galleries use an operating model that has remained almost the same since the 19th century,” Andrei Breahnă, one of Gaep’s co-founders, says. “It’s frustrating to see that you have an extremely valuable content, but you don’t use the means of the 21st century to distribute it.”

David Zwirner has been creating viewing rooms since the end of 2017, when he realized how much virtual previews before art fairs contributed to sales. Nowadays a pressing need, transitioning to the online can prove difficult in terms of resources for small structures, as most galleries are. Artists, gallery owners and collectors are simultaneously discovering this new way of functioning, with both its benefits and its disadvantages. But many are those who say that the chance to explore an artwork at ease, from your own home, without having to visit the sometimes intimidating space of a gallery, adds to the decision process an intimacy that numerous collectors, both seasoned and novices, will find comforting.

MARILENA PREDA SÂNC

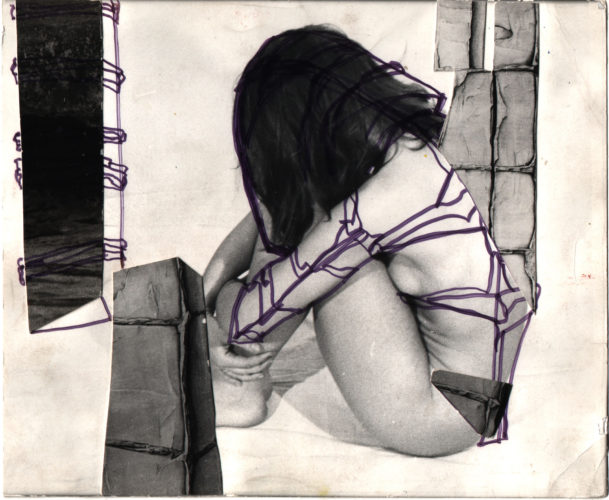

It is, in a way, something that naturally crosses one’s mind when absorbing the art of Marilena Preda Sânc (b.1955), the artist the Resilience Test online exhibitions series started with, on June 29. Some of the exhibited works are photographs with interventions, from the series My Body Is Space in Space, Time in Time and Memory of All, which she created in the early 1980s. Back then, the body had to withstand the social, cultural and political restrictions imposed by the communist regime. The artist’s naked body, pierced or framed by drawings that sometimes look like armors, sometimes look like cages, seems a macro-exploration of both the idea of vulnerability and the force of femininity. “Relating to the thoughts of Judith Butler,” adds the curator’s text, “the body itself is never only yours; instead, it is part of a matrix, of society and of various sociopolitical processes, in which it is understood, assigned, and distributed. These collages resist the matrix, directly and without compromise.”

Also back then, Marilena Preda Sânc could not display her works in Romania, so she used mail art to give them a chance to be seen at events from elsewhere. As she told ARTA magazine in 2018, mail art was a bridge to a forbidden world; controlled by censorship, but not completely stopped, it was a way to meet other artists and be in contact with them, and also a validation of some of her studio experiments.

The collages in the exhibition are naturally complemented by her early paintings – which she used to call body-landscape paintings –, them, too, an overdose of intimacy. Self-isolated from the political or social context, the body finds its escape valves, but it cannot be unbound. While the postures of the naked woman in the paintings and the titles of the paintings themselves convey peacefulness (Meditation, Abandonment, The Sleep), the background of the works conveys the exact opposite, outlining a feeling of “nowhere”, of staring into the darkness. “Different body positions in my paintings from the 1980s suggest the escape from a reality I didn’t want to be part of,” the artist says “and the immersion into my own subjectivity, always closely related to nature. For me, what unites body and nature is the wish for freedom.”

As she often said in interviews, Preda Sânc only became aware of the feminist voice in her work after the Revolution, when she could attend exhibitions in Europe and learn more about the feminist art movement of the 1970s. The fall of communism also gave her the opportunity to discover video as an artistic medium and expand her practice through videos such as Inside (presented in the exhibition), through which she explored gender identity.

VLATKA HORVAT

The human being caught in a perpetual state of uncertainty is also reflected in the work of Vlatka Horvat (b. 1974), who has been investigating, in numerous ways, the relationship between body and space. Born in Croatia and currently based in London, Horvat is known internationally for installations, performances and works on paper that explore how social systems transform and fragment the body’s image and functions. “I’m particularly interested in the relationship between a human body and the context in which we operate,” she says. “Often my projects are driven by the question of how space and the way it’s organized might affect, influence, dictate, even determine our behavior, movement, choices, etc. in it.”

The body’s interaction with ordinary objects, another specificity of many of her works, is also found in Resilience Test. In Monuments, a photo series from 2018, the artist “captures” her hand holding materials and utilitarian objects: pieces of wood, a brick, a rubber glove. A detached observer of her own hand, a contorted body and a “monumental” object at the same time, Horvat invites you to play with interpretations and ways of looking.

“The vulnerability and diminishment of the body on the one hand, and its obtrusive, inarguable presentness on the other, are two forces at play in Horvat’s work,” says writer Naomi Fry in a text entitled Tragicomicomictragic.

The artist has the habit of hiding in plain sight in her works, whether it is in photographic series such as Hiding (Outside) and Searching, or in Hybrids, a series of collages exhibited by Gaep, in which fragments of images of the artist’s body are merged with images of mundane objects, the end result seeming to have come out of the drawer of a creator of bizarre animations. The body becomes a modular object, a lego piece with interchangeable identities. “As in much of my figurative work in collage,” Horvat explains, “the body and the elements of the physical world are proposed here as sites of fragmentation, collapse and failure, but also re-imagined as sites of repair, possibility and play.”

An awkward hiding and fusion with an object “from around the house” is also seen in the images which resulted from Unhinged, a six-hour performance from 2010, during which Horvat danced and fought with a door removed from its hinges, through the spacious rooms of a historic mansion. “I once described her practice as a relentless knock-knock joke,” says American artist Graham Parker of Horvat, adding that what on the surface looks like deadpan humor has an undeniable melancholy underneath. This quality of her work is evident in Unhinged, where she and the object are forming a hybrid being, both trapped inside and locked on the outside, which completely destabilizes the meaning of the door. The artist tries to pass for a door and walks with the door between visitors, questioning things like the (in)visibility of the domestic worker (one of the themes of the performance), but also the idea of limit or edge – where the body ends and the world begins, where the outside becomes inside, where the private becomes public. Viewed in the context of this past spring, when closing the door was a gesture of self-protection, but also of submission of the will, of hiding from reality, but also of not being able or allowed to go outside as much, the dance of this door-woman through a huge house that does not seem to fit her becomes all the more charged with meanings and therefore all the more enigmatic.

It’s hard to look at Resilience Test completely detached from the upheaval of the world as we knew it, and that’s why the highlight of the segment that Horvat occupies is probably Balance Beam # 0320, an installation she made for Kunsthalle Wien at the beginning of the year. Seen as a political work by the artist, it consists of three long wooden beams resting on the backs of chairs and stretching 15 meters across the room. Dozens of objects are lined up on them, all spherical or cylindrical, all in a gymnast’s balance. Caught between a fragile stability and an imminent fall, the objects’ position is similar to our certainties regarding the immediate future. “It’s balanced, but only just,” Horvat explains in the video accompanying the installation. “Structures, and institutions and countries, and everything that at some point seemed solid and taken for granted is now feeling like it’s quite shaky and in this sort of state.” For the online viewer, Horvat’s guiding voice fills the gaps left by the impossibility of being in the same room with the work and also reveals the limitations of an online exhibition and how much it relies on imagination, on taking time to close any other tabs and pay careful attention for a few minutes. Horvat talks about the installation as a gesture through space, which can be seen both as a bridge and as a barrier, about an active relationship with the visitors, while they are confronted with such an insecure balance.

“Ever since my first sculpturally focused show at the Kitchen in New York City in 2009, the presence of the viewer in the space and in the proximity to my constructions has been extremely important,” the artist said for this article. “The viewers activate a set of questions the works pose – by being invited to position and reposition themselves in relation to my sculptural propositions. In Balance Beam, for example, (…) the presence of the viewer becomes crucial to keeping (or not keeping) these objects balanced. If you come too close, bump into the structure, or even just stir the air around these objects a bit too much with your motion – all these actions and accidents can unsettle this extremely temporary state of stability and cause an object to fall. And once one object falls, other ones may follow!” Horvat sees her construction as a system in which the state of equilibrium depends on a relation between all the elements – “a mutually affecting economy” –, including the visitor, who also becomes, through their mere presence, responsible for maintaining the precarious state of affairs and able to influence the way things will go. If they fall, the objects will be put back, the artist says with a smile in the explanatory video, and that characteristic mix of humor and melancholy sizzles like an effervescent tablet. But the need for complicity and care remains. We are all responsible.

IŠTVAN IŠT HUZJAN

Resilience Test started with the body in its small details and ends, in August, with a meditation on what we can discover and convey when we set our bodies in motion.

Declaring himself close in thought to the artistic groups Gutai and OHO and recalling the practice of the walking artists of the 1960s and 1970s such as Richard Long, Hamish Fulton or Neša Paripović, the Slovene Ištvan Išt Huzjan (b. 1981) uses walking to analyze the distances between people and spaces. For him, his very special relationship with walking started early on. He grew up at the edge of the south side of Ljubljana, which was occupied by fascist Italy during World War II. After the liberation of the area by Slovene partisans on May 9, 1945, the barbed wire barrier installed by the Italians was replaced by a short trail, as a reminder of the occupation. Since 1957, every year on the anniversary of the liberation, the citizens of the capital walk the trail together. “I was born just next to this trail that is today a 7m wide gravel trail with memorials along side it,” Huzjan said for this article. “Every year on 9th May, we would join the walk with my family. It was great. People met, ate together, discussed daily politics and, more than anything, remembered the awful past.

Through this experience I learned at an early age that sometimes we walk not to get somewhere or to exercise but that this way we also protest. In our case to make sure Ljubljana never becomes a fascist place.”

The artist used to measure and explore the world with his body when he was a student at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Venice, and he still does it today, when he divides his time between Ljubljana and Brussels. In his practice, steps become a unit of measurement not only of personal experiences or interpersonal relationships, but also of society and of his many historical or geographical interests.

In Wanderlust, a precious ode to walking, writer Rebecca Solnit dwells on “walking artists” and says something about Richard Long that also applies to Huzjan’s art: “His brief texts and uninhabited images leave most of the journey up to the viewer’s imagination, and this is one of the things that distinguishes such contemporary art, that it asks the viewer to do a great deal of work, to interpret the ambiguous, imagine the unseen.”

Line Umpire is a 2018 performance during which Huzjan walked for three days (8-10 hours a day) on the invisible, 65-kilometer circular border of the Brussels Region, wearing a suit in the colors of the Belgian flag: a black leg, a red leg, a yellow torso. A local who spoke neither French, nor Dutch, and whose journey was visually documented by his girlfriend.

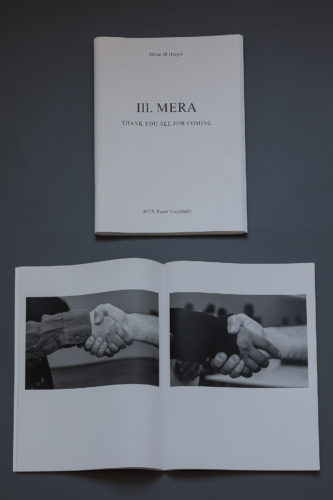

Like Richard Long in the 1960s, Huzjan comes up with performances that he documents not necessarily in an exhaustive manner, and which are traversed by a tension between the material and the immaterial. He later exhibits photographs that mark his approach, and also found objects, little sculptures he makes in the studio, and artist’s books, a sort of travelogues. Resilience Test highlights MERA, three books about three performances. A walk along the Belgian coast, between the Netherlands and France, with one foot in the water and the other on land, is marked by a photograph of the horizon facing south, taken every hour. On the occasion of an exhibition in New York, the artist walks on 5th Avenue and collects garbage from the gutters in six transparent, 60-liter bags that he eventually leaves in front of the gallery. At the opening of his de Métrico a Imperial solo show in Mexico, he shakes hands with all the visitors (about 100 people), greeting each one of them with a “Thank you for coming.” “People felt dignified and felt they are there,” Huzjan told me, “not in a historical reference, not in a store, not at a drinking party, but there, with the artist. And so they asked me a lot of questions and engaged with art.”

In his shows, Huzjan often exhibits found or kept objects, on which he sometimes intervenes in the studio. Six horizontal sculptures, plaster copies of walking sticks used during different performances, become traces of walks through Slovenia, Belgium or the USA, some of them solitary, others in the company of a curator, an artist or of larger groups.

Having started from Marilena Preda Sânc’s body, a deeply free one, albeit censored by communism and sealed between borders, Resilience Test stops in the immensity of the space between an artist and a curator who create something together from opposite ends of the world – one in the Mekong archipelago, the other in The Peruvian Andes. From Sunrise to Sunset puts the greatest possible distance between them, and the moment they share – the summer solstice – is documented by photographing the movement of the sun across the sky, a sun which sets for the artist, while it rises for the curator.

Distance turning into art also appears serendipitously in the online discussion that curator Tevž Logar had with Vlatka Horvat, on the occasion of Resilience Test. Horvat tells him that since April, she and her life partner, artist Tim Etchells, have used a GPS app to generate a drawing of their daily walk, each on their own phone, which they later annotate with pictures, small observations or situations they encounter. The habit remained even after lockdown eased, so now they have over 160 such diptychs, the artist says in a video which adds tens of extra fragments to the puzzle of the online experience that Gaep offered us this summer.

“Our goal was to start a conversation with the public, from here and from abroad,” says Andrei Breahnă towards the end of an organizational marathon with an optimistic finish. “We are in an extraordinary situation, namely that we produce these exhibitions at the same time as the big galleries in the world. We are not behind on this subject.”

POSTED BY

Gabriela Pițurlea

Gabriela Pițurlea is a freelance writer and editor. She studied Journalism and Advertising, and started by working as a reporter for Esquire Romania and DoR. She is the co-founder of SUB25.ro....

Comments are closed here.