The title of the current exhibition by Larisa Crunţeanu and Sonja Hornung, “Femina Subtetrix”, suggests an underlying feminist counter-narrative, a pseudo sci-fi speculative invention perhaps. This initial assumption is not entirely off the mark: what the show at Ivan Gallery delivers in visual content is far surpassed by the conceptual research and contrivance forming its basis. The subtleties of the sparse exhibition rooms on the ground floor of the converted villa – with their concrete blocks on pedestals and small, framed photographs cornering the room – conceal many layers of theoretical and historical analysis at work.

Crunţeanu and Hornung began their research as part of a residency at ODD. They were primarily interested in the history of the APACA textile factory, located near the Politehnica metro station in Bucharest and acting as the spatial and thematic nexus of the show. APACA plays an important role in the Romanian imaginary, as a steady source of employment for women in the communist period and maintained its iconic status even after its privatization and eventual closure . ‘The girls from APACA’ became well known following Prime Minister Petre Roman’s legendary visit to the factory, at which time the women are said to have chanted in unison: Nu vrem bani! Nu vrem valută! Vrem pe Roman să ne fută! (“We don’t want money! We don’t want hard currency! We want Roman to shag us!”) The factory employees were embroiled in rumors about their sexual prowess, at once admired and vilified, and became recognizable social symbols at a time when workers were often used as powerful ideological tools.

“There are a series of images that are presented about the women of APACA, that fed a kind of propaganda machine,” Hornung tells me. “There were 18,000 people working there in the 80s, so it became a kind of showroom. Gorbachev and the Chinese diplomatic contingency visited the factory. It was a space where fashion, power, and everyday hard work came together… There was a process of image production in both the communist and capitalist periods. People always contrast these systems, but in the end a personal element gets lost in the motivation to create popular support, and to produce images and cash. In the case of our research, it’s the hidden sacrifice inside the edifices of progress that surround us.”

The word fabrication follows me throughout the opening of “Femina Subtetrix”. Fabrication has a threefold connotation here that corresponds to the preoccupations of the show: the construction and privatization of the APACA factory, the material production of the commodities that the factory sold for generations, and the tale woven by the media, politicians and the artists themselves (the “agents of speculation”). Crunţeanu and Hornung purposefully straddle the tenuous borders of myth and reality, aware of their ability to shape future understandings of the space and taking their privileged role as historical producers to the level of public performance.

The pair has assumed the task of reading and writing history from the perspective of its ‘subtext’. Walter Benjamin writes in his theses “On the Concept of History” that “the subject of historical cognition is the battling, oppressed class itself” and quotes Nietzsche: “We need history, but we need it differently from the spoiled lazy-bones in the garden of knowledge.”

While, over decades, the media unfurled a story befitting the dominant discourse, of “the girls of APACA” as both economically integral and sexually powerful and, eventually, dispensable, Crunţeanu and Hornung present their story from another, rarely explored vantage point. Examining the empty lot where the factory was said to be located, both on foot and via drone footage from a God’s eye view, they parody the vocabulary of state surveillance and so-called journalistic objectivity by reading the spectral evidence felt in the space: it’s presence-through-absence, or “hauntology”[1].

In a publicly aired news segment for DIGICULT – a cultural program on TV channel DIGI24 – Crunţeanu and Hornung are interviewed as they stroll authoritatively around an empty field, the supposed wasteland of the former APACA factory, and recount a convincing story of Ana, one of the factory workers who, after being rendered unemployed and homeless, allegedly died in the demolition of the building. In a later conversation, they tell me that they are reversing a well-known architectural-religious Romanian myth, the story of master-builder Manole.

“Manole is constructing a church,” Crunţeanu recounts. “Every evening it falls apart. The building won’t stand. Then he has a vision: he is told that the church requires a human sacrifice in order to stand. The first woman who visits the site will be the one who is built inside the walls of the church. All the men warn their wives not to go there, except Manole. Ana, his pregnant wife, comes to visit. He tricks her and tells her they are going to play a game: he builds her into the wall of the church and by the time she realizes, it’s too late. The building stands up, thanks to this sacrifice. They say you can still hear her in the building. This idea of a human sacrifice to keep the building standing was modified by us, to suggest that you need a human sacrifice in order to clear out or neutralize a space as well.”

By inserting the body of a dead woman into the landscape – a speculative and boldly inflammatory move – the pair have decidedly entered into the media myth-making that surrounds the area. They are provoking a consideration of a different history, that of the people who lost their livelihood (and, in some cases, their lives) with the privatization of countless factories across the country: the unheard and ubiquitous victims of capitalism.

As the curatorial text by Xandra Popescu eloquently insinuates, the show has a sustained interest in the gendered nature of labor: “our mothers of light industries, and fathers of heavy ones.” Yet the material used in the exhibition is often of the ‘heavy’ kind – with architectural elements taking visual dominance on the ground floor.

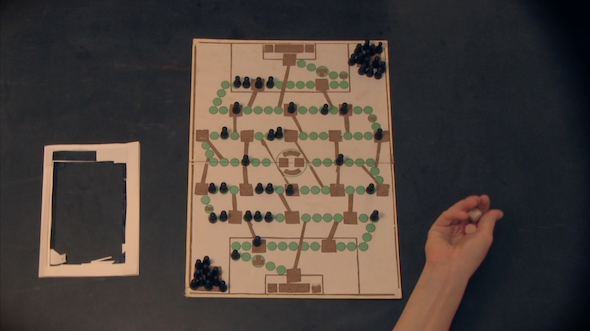

From the outset, visitors are subjected to a controlled circulation of the gallery space, and become pawns in the cleverly concocted game of the artists. There’s an overwhelming sense of being witness to the bond of the artist duo as they feel their way to collaboration, having been partnered together by the curator and seeking common ground. As visitors, we’re invited to participate in this through the first piece, where we literally reach into the cavernous hole in a concrete cube in the hopes of touching our partner’s hand inside. The experiment sets the tone of the game, whether we will find our match, a friend or foe.

The steps that follow reveal the aforementioned details of the APACA legend through cleverly crafted allusions. The red sweater, for example, serves as a metonymic signifier for the legacy of the first post-revolutionary Prime Minister Petre Roman. The portrait of two figures in an embrace, wrapped in red textile, references Roman’s condescension towards an APACA employee, wherein he kissed her forehead in a paternal gesture in front of swarms of cameras during a visit to the factory. We are invited to reenact that iconic gesture.

The same red sweater is then hung from a billboard, paying ironic tribute to the relationship between Roman and the transition to capitalism that took place under his watch. Other found and repurposed objects make up the ground floor exhibition contents, with a small fountain spilling what appears to be wet cement, a metaphor for “limitless real estate wealth” also considered through the lens of the APACA closure and neighboring developments.

On the top floor of the gallery, the game changes and we become passive viewers. Drone footage of the massive site captures Crunţeanu and Hornung as they follow each other in an infinite chase around the periphery. There’s no object to the game, except a tracing of the area. Yet unexpected figures emerge, even unbeknownst to the two participants, inscribing very real presences alongside the ghostly ones that call the site home. This is definitely not a dead space. It is alive with history and myth, and begs the question: what differentiates the two?

The intellectual rigor with which this exhibition was conceived is evidenced at every turn, despite (or because of) the childlike, interactive concept of the show’s presentation. Crunţeanu and Hornung are not amateur detectives, but convincing media manipulators. The word “mastermind” and its equally patriarchal synonyms are profaned in this powerful history-writing experiment.

[1] Jacques Derrida, Spectres of Marx (1993)

Femina Subtetrix is at Ivan Gallery in Bucharest between 10 September – 3 October 2015.

POSTED BY

Alison Hugill

Alison Hugill (1987, Canada) has a Master's in Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, University of London (2011). Her research focuses on Marxist-feminist politics and aesthetic theories of community, c...

www.alisonhugill.com

Comments are closed here.