On a beautiful and sunny Sunday, one of those special transition days from Summer to Autumn where the air is fresh and crisp but not quite cold, where you use the peace and pace of the weekend to reflect on recent events and prepare for what’s ahead, I decided to pop into the National Art Museum of Moldova to visit the exhibition “aCASĂ / My Home” curated by Valeria Barbas and dedicated to the last six months of the Ukraine crisis.

The use of mixed media was immediately captivating. I could see this would not be a 5–10-minute walk through. There were engaging works of video art such as Ghenadie Popescu eating the talking Putin, that invited you to put on headphones and “consume” rhetoric differently; pieces of wet, live dirt sent by Marta Romankiv from Poland, the country that received the highest number of Ukrainian refugees and a new home for many Ukrainian artists that made you want to reach out and feel its cool surface; photography, paintings and provocative posters that made you grateful for the wit and wisdom of humankind. All of this was set to the backdrop of Chopin’s nocturnes – wait, Chopin?! I’ll come back to that. The mixture was superb, but perhaps the only thing missing was a station toward the end where the viewer could also create and contribute to the dialogue, for none of us are immune to the current context. We all have feelings, emotions, voices; often not fully expressed. The exhibition “aCASĂ” was inspiring in this regard. It demonstrated that the Moldovan people, as well as its diaspora and the Ukrainian artists living amongst us, are not as docile and dormant as first thought. The art works on display reminded us all to speak-up as the horrors of war and loss of home, shall not be borne lightly. We have a duty to stand-up for safety, security, and protection of all God’s creation. In this way, the exhibit accomplished its mission. Not only did it raise awareness, but it was a powerful call to action – solidarity at minimum, but much, much more if we are open to it.

There were notable individual works. The collection of photographs, for example, by Mihail Călărășan was the first display if moving from left to right. Each individual image was exquisitely done, both the content and composition. I could have spent hours just admiring this one wall of photography, but interestingly, the images were quite small. Although far-sighted myself, I found I had to get quite close to each image to fully see the figures and landscapes depicted; while doing so, I found new layers of beauty. With my face pressed close to the wall and enclosed in a corner on left and right, I got the sensation of suffocation or claustrophobia, a simulation of what Ukrainian families must be feeling as they look toward their future. The wall in front of them seeming debilitating and insurmountable but the tenderness of ‘home’ displayed in the images creating a holy center that gives us strength and makes surroundings bearable.

The neighboring piece of photography by Teodor Ajder was also powerful. An artist turned impromptu clown during the wave of refugees coming across the border, Mr. Ajder’s work features a balloon animal of different sorts, one of a human being bound and imprisoned. The image and its contrast with childlike joy that typically stems from balloon shapes is strong, but it is amplified further. The color of the balloon, in a pale, neutral tone, is reminiscent of a condom. Perhaps unintentional, it conjures the complex emotions Ukrainian men must be feeling at this time – in some ways proud to fight for their country, in other ways constrained and helpless to protect their families as women and children flee to safer ground. I think also of the many men inside Ukraine – including those who are transgender – who may be opposed or simply afraid to fight, who are now obligated to risk their lives, hands-tied, now bound to serve. All of this takes on an even more personal message with the title, “Prisoner / Self-Portrait.” With the message of “self-portrait”, the artist suggests that he is also bound in some way, perhaps we all are, in the way that we respond to this war or in how we live our lives. This is an interesting take on ‘home’ as an expression of how we live rather than the physical space. Perhaps it is the safe choices we make to find comforting protection of home that ultimately imprison us. The artist cleverly notes how the natural deflating and disappearing element of the balloon is thwarted by capturing it in photographic form – an important reminder of both the passing and permanent state of our own imprisoned existence.

The painted works from refugee children in temporary assistance centers in Moldova are bold and eye-catching. The works were the result of workshops provided by the expo’s curator Valeria Barbas. One can sense immediately the exercise that likely transpired, children of all ages and backgrounds gathered around the edges of large-format canvases to create an image together. The colors are brilliant and as one would expect, some of the images are more somber and sadly militaristic than others, a clear message of homes destroyed and the adoption or adaptation of new homes in Moldova. At the end of the series there is a blank white canvas with a note on how the canvas could have been painted by children had there not been 977 killed by war to date. While I appreciated an effort to drive-home (no pun intended) the reality of war and its effect on children, this expression felt a little cheap and cliché and not in line with the messages of the former canvases. The preceding images were not painted by children inside Ukraine but those who fled to Moldova and were having to conjure a new meaning of home. This is entirely different from the message of lives lost within the borders of Ukraine, unless the blank, whiteness is supposed to suggest some kind of pure heavenly home to which these young lives went, but this feels like a stretch.

A collection of additional paintings continues along the adjacent wall with varying degrees of interest and intrigue, dependent – in my opinion – on what is on the mind of the viewer. The voice or message of the artists get a little lost in this collection, as well as their connection to the ‘home’ theme, but I found several of these works quite interesting and provocative, such as Iurie Puzdrovschi’s Refugee – representing a foot with the amputated big toe – due mostly to my own narrative and imagination. Several were aesthetically pleasing, or not but in provocative ways. However, the centrally located assemblage of video art works and tactile sculptures was too attractive for the paintings to hold my attention for long. I was intrigued in particular by Alex Avega’s depiction of home, his last memory of it, before fleeing and leaving it behind, perhaps forever, in plaster upon a piece of plywood that presumably stems from shelter-remains. The clean white plaster attempting to gloss over and repair the dark, damaged wood below in a quick-drying effort was evocative of what so many Ukrainians are currently striving to do: salvage what you can and bolster the spirit for the road head.

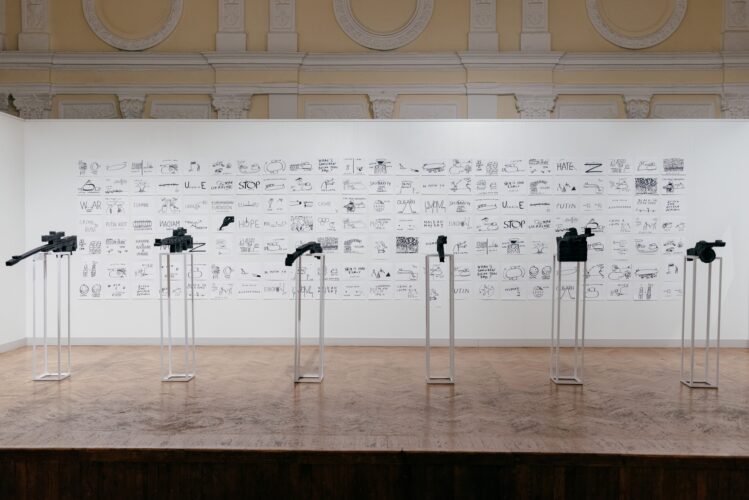

Then onto the final wall of works, but halt! A series of half-dozen molded war weapons (works by Valeria Barbas) stood aimed directly at me, stunning me in my path. While I knew these were fake, their scale and precision were dramatically life-like. Having never stood in front of a firing squad myself, the emotional reaction was visceral. I was profoundly moved by the terror of it. Unlike real life, these weapons were not held by humans. They seemed to float in mid-air, standing in a vacuum, devoid of the killer behind the butt of the gun. Both a blessing and a curse, you could somehow detach from the reality of it – having a human figure there would have been entirely too unnerving – but the emptiness and open vacancy also seemed to indicate that it could be any of us behind the gun. Indeed, the viewer was in fact invited to go up the stairs and stand behind the guns in order to see the next exhibit. As I did so, my back accidentally brushed against one gun making a terrible scratching sound as it moved inadvertently into a diagonal. As I attempted to “fix” the exhibit by straightening the gun, the surreal experience of re-aligning, nay, aiming the gun into its rightful place was extremely disturbing. I shivered and shook-out my hands.

Behind the guns was a wall of drawings by Dan Perjovschi featuring black marker on white A4 paper in a table-like matrix format. At first glance, it appears these are also children’s drawings like the paintings on the opposite side. But upon closer inspection, one can see that these images create a series of witty political statements. There are poetic and provocative plays-on-words and intentional designs to communicate meaning. It almost reminded me of a riddle or puzzle you solve as part of a party trick. These were so thoughtfully composed that one can only wonder why the artist chose to repeat several of the pages on the tableau instead of simply reducing the scale of the matrix. Perhaps the artist sought to simulate a type of silent demonstration, where protesters in the crowd sometimes hold up posters of the same message that were mass-produced for the event – some catchy saying that caught the attention of more than one dissident raised high in display.

In addition to individual works, the curation itself and interplay of works was also artfully done. With the exception of the children’s paintings, the vast majority of pieces were done by artists born in the 1970s or plus/minus five years. This generation knows insecurity and war first-hand, a powerful reminder of the significant population in Moldova and neighboring countries that is likely living with post-traumatic stress as experiences once buried come to the surface again. Logistically, the exhibit was set-up nicely, moving from photography to painting to a black and white installation on the stage and the interactive core pulling you in. In essence there were hand drawings on either end of the room. On one side, the colorful acrylic canvases painted by the refugee children. Their childlike enthusiasm apparent with brilliant sweeps of color dragged and pushed across the surface, perhaps by fingers in some cases, others by brushes now left anchored in the paint itself. Opposite this colorful wall we find the intense scene of black and white marker drawings. The contrast of the two: one colored, one black and white; one wild and abstract, the other quite thoughtful and intentional; one child-driven, one adult – is poignant. The energy of the children’s emotions replaced by the precision of the adult’s as one progresses through the exhibit. Between these two works stands both the installation of mixed media but also the precariously-positioned weapons. From the vantage point of Mr. Perjovschi’s drawings, the guns are aimed directly at the children’s paintings. Message received.

There were some limitations to the collection. There was such a volume of work that in some cases, the collection began to stray from the theme. Many pieces were simply artistic expressions of political resistance rather than communication on ‘home.’ This approach was somewhat palatable as the borders of Ukrainian homeland are indeed political in nature, but it almost felt like two exhibits grouped into one. To be fair, the introduction to the exhibit states that it only “starts from the concept of home, or what it means to be at home” and indeed it goes on to cover much more. Furthermore, while Chopin’s nocturnes are put into context once you view the work to which it corresponds, it was immediately jarring when I arrived on the scene. I thought it was a haphazard attempt to provide light ‘elevator music’ in the background of the exhibit while viewers moved among the works. I was confused about why Chopin, of Polish-origin, was adopted for the track instead of one of the many great Ukrainian masters and why the same song played on repeat instead of circulating among other great works. Perhaps with more space, the video work to which the soundtrack belonged (Pavel Brăila’s) could have had its own space so that the majestic nocturn did not infuse into the other neighboring works, some more jarring in nature. The contrast was not intentional, though we can certainly find meaning in it. Here we are enjoying a refined and sophisticated trip to a gallery, in a grand ballroom with eloquent music, while the disgusting and abhorrent slaughter of war takes place nearby. Again, message received. But this was an unintended juxtaposition, as far as I understand it, which makes the meaning a bit forced. Still, it had an unintended consequence within me as well. In some ways, I couldn’t face myself by the end: leisurely walking across herringbone hardwood on a beautiful day, lighted by chandeliers with a pianist tickling the ivories in the background. My cocoon of culture, my comforting home, was suddenly unacceptable.

I lived briefly in Kyiv (Dec 2021-Feb 2022) and felt its spirit and vitality immediately. As a result, I was quite moved by Pavel Brăila’s videographic work at the end of my tour depicting a single pink ribbon, dancing through the air like an elongated kite’s tail across iconic areas of Podil. The images were intentionally beautiful and dreamlike, which is why ultimately Chopin’s nocturnes played in the background. Any such lullaby could have sufficed, but the choice of Chopin was interesting as Chopin himself was an immigrant who fled Russian occupation. As these rich and soaring aerial images appeared on the screen though, they were first introduced by the sound of an air-raid siren. The pink ribbon thus took on a different meaning, reminiscent of a smoke-trail of a missile going into your favorite parts of the city. Through this moving image, your imagination immediately leaps to the fear each Ukrainian must feel each day and the heart-breaking reality that these places we know and love, “home” itself and its meaning, is being destroyed – for us all.

The exhibition “aCASĂ/My Home”, curated by Valeria Barbas, took place at The National Art Museum of Moldova during 14th of September – 2nd of October 2022. Artists: Maria Kulikovska, Lia Dostlieva, Andrii Dostliev, Mariya Hoyin, Taras Polotaiko, Violetta Oliinyk, Daryna Gladun, Lesyk Panasiuk, Anton Logov, Alex Avega, Boris Gumeniuk, Zuzanna Janin, Teodor Ajder, Marta Romankiv, Anna Rutkowska, Pavel Brăila, Ghenadie Popescu, Mihail Calaraşan, Igor Svernei, Iurie Puzdrovschi, Mihail Puzur, Valeria Barbas, Dumitru Crudu, Dan Perjovschi, Tudor Pătraşcu, Edi Constantin.

POSTED BY

Britton Buckner

Britton Buckner is a transnational and world traveler. She’s spent the past 18 years working in the field of humanitarian assistance and international development, including five years in Moldova. S...

Comments are closed here.