About five years ago, I was dancing in a sweaty basement of a Belgian bar lost among the winding cobblestone streets between Nation and Montreuil. It was a dark, shallow space with visible red brick, not much larger than my living room. There were posters with horses on the walls, six tables on the side and a minuscule stage. It reminded me of those rockers’ bars we used to have in my hometown in old cellars. Only, instead of long haired guys in black band shirts headbanging to ’90s rock hits the crowd was a mix of punks, hipsters and crusties gently swaying to the wailings of a ’70s Iranian singer and Turkish songs we would play at our house parties. How was this possible, where the regular Parisian dancing venues were a combination of indie, rock and roll and Balkan music?

For the closing night of an international hacktivism festival, the programmers chose a circuit bending A/V performance, an 8-bit noise show and a German DJ playing all sorts of non-western sounds to the handful of people that braved the overheated basement. He keeps pulling gem after gem from his record bag with an enthused, nonchalant smile, as if it were the most normal thing to be doing on a Saturday.

Coming from the highly segregated Romanian party scene that back in 2010 was still dominated by indie/electro sounds as the official underground soundtrack, it seemed unconceivable that the silly, lo-fi sounds popularized by labels such as Sublime Frequencies would ever leave our Ipods and bedrooms.

On a warm night at the beginning of July, some 200 people are doing their best belly dance impression on the generous dancefloor of the Berlin room in Control Club guided by the steady hands of my old German friend. With an equally infectious smile, Sebastian aka Booty Carell is spinning mostly bassless music to a happy crowd that has miraculously not fled to the neighboring techno room or the smoke-friendly terrace. It is 2016 and this was just one act of Outernational Days, the three-day festival celebrating this niche.

The sheer existence of this sort of event, especially in a context like Bucharest, is a pretty huge, almost miraculous deal. The task of putting together three full days of concerts, complete with debates, workshops and club nights, sounds like an overly ambitious task and possible financial suicide, especially without corporate sponsors. Their strongest bet must have been world music’s wide-range appeal : it’s the genre clubbers, indie kids, metalheads, jazz cats and their parents could all enjoy.

In the context of post-Colectiv Bucharest, everyone thought that the buoyant nightlife that made the city so vibrant might sadly disappear. For the first few couple of months, things seemed pretty bleak, with an array of cancelled events and a shortage of venues. However, this scarcity, combined with the gradual relaxed attitude towards the draconic newly-instituted security rules lead to a wonderful new wave of initiatives and urban renewal.

Take just the most recent events from this summer, for example – there’s Cabal, a cool series of daytime parties in the Botanical Garden, the revival of the Ponton bar in Carol Park, host of many underground parties and dubbed the local Club Der Visionaere, the opening of community-ran space Macaz and the recent move of Expirat to Halele Carol, a previously improvised location.

While these initiatives still function within the (often) sponsored house/techno paradigm (with the expection of Macaz), it’s the true DIY events that made a splash with bold curatorial choices and unexpected approaches to long-established formulas. The real magic happened at the controversial Interval experiment, the under-the-radar Nightshift parties and now, Outernational Days. These share the same pioneering attitude towards change and a certain idealism that more often than not leads to poor attendance and financial loss, unfortunately. However, it’s these sorts of risks that slowly bring a change in attitude from both audiences and promoters, especially in a context where people have to fight with a particularly difficult financial and geographical context.

Promoters have to solve an almost impossible equation of interesting, financially-viable events where everyone gets paid, while maintaining the cover cost somewhere under 5 euros. In order for this to work, you have to either draw a very large crowd or rely on corporate sponsorship that somehow maintains the aggressive ubiquity of the ’90s. If this wasn’t enough, you’re also catering to the same roughly 5-600 people that go to Control/Rokolectiv, unless you’re doing minimal/ar:pi:ar or stadium house parties. More often than not, rivaling promoters fighting over the same audience book conflicting events.

I know this is actually a strategy in the contemporary art world, so that people out for an opening would make a whole evening out of it, visiting 2-3 galleries, but for the party scene paying the cover/cab fare for different clubs/parties isn’t usually the case, except for other people in the industry and a couple of die-hard clubbers.

To be perfectly honest, I was a little skeptical of the outcome at Outernational Days; of course, it was an incredible line-up, combining long-time crossover legends Konono No 1 with locally-acclaimed musicians like Harry Tavitian and Dan Armeanca, in a cross-genre attempt to draw together everyone from the progressive clubbing/hipster scene to jazz lovers, artists supporting the cool manele scene associated with the Paradaiz group, as well as roma people, who are mostly ignored by the state funded events circuit. Sandwhiced between those headliners were also local heroes Khidja performing their first live ever, beloved manele cover band Raze de Soare, indie darling Vincent Moon and a handful of other musicians from Burkina-Fasso, Egypt and USA, as well as a few world-music friendly DJs, some of which already had a couple of successful club nights in Bucharest.

The density of the line-up feels both decadent and utopic; after a series of dedicated concerts and parties over the past couple of years, blowing up this micro-trend into an entire three-day extravaganza feels like an immense leap of faith. Or is it really that unrealistic? Considering the efforts of DJs like Bogman, Khidja, Tzuc, Dragoș Rusu and Scoro of bringing more non-western sounds to the dancefloor, one would say that the growing popularity of world music parties, as well as oriental-sounding hybrids such as Acid Arab and the rise of the ethnic-influenced techno/EBM sound have paved the road for an event like this to happen. Not to mention the newfound interest in manele.

Starting roughly around 2011-2012, Bucharest has experienced a unique period of openess towards alternative sounds, mostly oriental/world music-influenced. Take for example the crusade lead by people like Adrian Schiop, Cristian Neagoe, Ion Dumitrescu and the Paradaiz group for rehabilitating manele, the gypsy-gangsta genre that has been banned from public radio and TV in the mid-aughts by the political elite. Despite large strides made towards the acceptance of (certain) strains of the genre by the underground intellectual community, it remains a peripheral, largely demonized genre, bearing a heavy social stigma.

Trough Murky Waters

It is difficult to approach the subject of the festival and its curatorial choices without addressing the manele debate which, despite gaining more acceptance than ever, remains a very polarizing subject, that still sparks an alarming number of overly aggressive and downright racist reactions.

From the wildly-popular Ferentari party at the CNDB back in 2011, a certain movement began to take place in making manele cool, at least among the cultural elite, militating for openess and social justice for all minorities, be it gays or Roma people.

Groups like Steaua de Mare, who gained international success by doing psychedelic-instrumental versions of certain manele standards, or more recently Raze de Soare, are very specific hybrids that managed to bridge the gap between manele and the snobism of more intellectual audiences. Although, while rooted in manele tropes and orchestration, their approach is so modern and unique that associating them with the genre would seem like a gross mislabeling. In a way, they’re taking the less ethnic-specific, controversial part of the genre and presenting a slightly white-washed version.

Yet, despite the utter success and general appreciation of these attempts, controversy struck again when the newly-founded Eden club broke off the purity of its club roots by bringing Romeo Fantastik to play in 2014, which resulted in an equally memorable party and racial war on Facebook. Our long history of passive-aggressive racism towards the Roma people and general Eastern shame, coupled with an overwhelming desire for occidentalisation is still deeply ingrained in the social fabric.

I remember when I was in junior high; manele was the ubiquitous soundtrack of my teenage years, from field trips to school dances. The only people who didn’t like manele were the overly prude teachers and us betas – the geeks, dorks and dweebs who weren’t cool enough to smoke and had a universal aversion to sports. Except for the rockers who were usually a minority functioning by their own hierarchy, the cool, strong kids were the ones going out and having fun, mostly to manele. And, to be honest, they were quite intimidating.

The long anti-manele crusade made sure to create an almost involuntary association between the genre and a low social status, stupidity and racism; it was a downright fear-mongering campaign, transforming the roma and manele listener into everything that was wrong with the country.

It seems that no matter how much progress we’re making, we’ll always seem to find a way of looking down upon it. Yet should we really strive for fully rehabilitating manele? Do we really want it to become a mainstream, integrated genre or should we accept it as a marginal, yet widespread phenomenon on its own merits?

However, the attitude that prevails is still one of exoticizing the genre and not an attempt for integration. The interest in proto-manele, the early ’90s genre with sparse instrumentation, naïve lyrics and oriental motifs quickly grew, facilitated by the archival work and events organized by Paradaiz.

All of a sudden, we were within a new paradigm: manele was no longer the embodiment of the lack of culture or an expression of stupidly-absurd kitsch, but a genre that could be appreciated on its own merits, before being perverted to the later dance/hip hop hybrids with idiotic lyrics.

Now, after racial wars and unanimous underground acceptance, we start talking between good and bad manele, focusing on the very select examples curated from ’90s tapes or ”purer” forms of the genre, that rarely resemble the logic of wedding dedication-driven and reverb-drenched vocals of more contemporary examples.

In a world where Omar Souleyman has become an international superstar, would it be so hard to imagine a similar path for our wedding singers? I believe the next step in the legitimization of manele would be receiving the seal of approval from a respected label/institution such as Sublime Frequencies, for example. Which may not be as far away as it sounds, given that Hisham Mayet expressed interest in a couple of Florin Salam tracks on his last visit to Romania.

Ultimately, there are a lot of Omar Souleyman detractors, from people calling him a sell out to those who downright hate his music. Yet this fascination toward his persona still exists and while a lot of my friends wouldn’t necessarily listen to his music at home, they would go to a show because of its entertainment values. And, believe me, an Omar show is nothing if not fun!

In the end, instead of trying to transform manele in a kind of cult genre, we should simply just embrace its over-the-top, camp values, beyond ironic liking or dismissing it as ”drunk music”. I believe everyone could find a couple of songs they might like from its many strains. It is, after all, a form of musique populaire and however cool and socially-accepted it may have become in certain milieus, there should also be absolutely no shame in expressing one’s sincere dislike.

In an ironic twist of faith, after the many waves of pro-manele propaganda, one might start to feel out of place if they didn’t appreciate the genre. Probably the best attitude would be one that goes beyond our social context and history, in an ideal world where things are simply appreciated for what they are and not for what they represent or have been associated with.

A large number of foreigners, coming from a more neutral background, have expressed sincere appreciation for manele, not without a certain exotic bias.

Outernational Days has found a way of avoiding the debate altogether, simply by arguing that manele is part of the outernational world by default, along with other marginalized contemporary genres such as electro-chaabi in Egypt, chicha in Peru and dabke in Syria. This categorization, championed by Ion Dumitrescu in his essay The Outernational Condition and Dragoș Rusu in his podcast series, is a very clever loophole which emphases their peripheral aspect, while playing the social injustice card, as well as placing them in a relatable, cool world music context.

The Attic Magazine, Dragoș Rusu’s brainchild, started about two years ago as a much-needed open music platform in the Romanian context. In the post-blog era (I’m talking about the nerdy, overly specialized download+review blogs such as Mutant Sounds or Cookshop), an online magazine with curated yet diverse content felt like a breath of fresh air.

The platform was constructed in the spirit of sharing, by bringing together any interesting piece of music, be it old or new, contemporary or electronic, reviewing both Larry Heard and Alan Bishop in the completist editorial spirit of publications such as The Quietus or The Wire Magazine.

After curating a series of concerts and club nights in Control, the idea of a festival comes as no surprise. Given the Outernational concert series initiated by Dragoș Rusu last year, which brought musicians from Mali, Thailand and Iran, among others, Outernational Days feels like every music nerd’s wet dream.

In many ways, the line up felt both excessive and overly academic; actually, the entire choice of dubbing the event ”outernational” felt somewhat rigid. Because, what is outernational anyway? The only other place I came across the term except for The Attic was at Hardwax, the techno-friendly Berlin record store.

On one hand, using a different terminology for the type of new world music promoted by labels such as Sublime Frequencies, Awesome Tapes from Africa, Finders Keepers or Pharaway Sounds doesn’t sound like a bad idea, in an attempt of differentiating the old-school, dusty ethnographic recordings and cheesy Peruvian pan flute CDs from this contemporary approach to world music that focuses on more hybrid, electronic, even pop sounds rather than ”primitive” music.

In his essay, Ion Dumitrescu defined outernational less by the music it produced and more by the modus operandi: this music was marginal, outside of the traditional studio/distribution/concert circuit, operating on its own terms, be it within the wedding industry like dabke, or through tracks distributed directly from one cell phone to another, as in the Sahel Sounds compilation.

It also applies to music from the past that due to the political situation in certain countries, has never reached western audiences.

However you put it, both world music and outernational are equally polarizing terms, built around a western-centric mentality and suffering from a certain amount of cultural canibalism. While world music has been presented as a form of refined art which supported a system of people sharing their culture with the world, the outernational attitude reflects the opposite. In outernational, there is no desire among the musicians to step outside their territory and reach larger audiences; instead, foreign audiences come to them and export the sound. People like Hisham Mayet and Brian Shimkovitz act as gatekeepers between these isolated communities and the civilized West.

While choosing the word outernational over world music might seem both painfully specific and progressive at the same time, it still suggests a certain form of oppression; although, building a festival around a lesser-known term that is still being defined provides some much-needed flexibility.

Outernational Days sounded like a beautiful yet utopic attempt, a brave but overly elated financial disaster in sight. For many days before the event, it did seem bound to fail, as if it was too good to be true. Presale tickets faltered despite the aggressive media campaign, and, just two days before the festival, the headliners, Konono No 1 regretfully announced they had to cancel, due to visa issues.

A Not So Secret Garden

Despite all the turmoil, come Friday, something wonderful happened: somehow, it all magically came together on the first evening of July at the Uranus Garden. Everyone and I mean everyone was there, from Cosmin and Mihaela of Rokolectiv, Octav and Anamaria of Sâmbăta Sonoră, Bogman, Mihai from Color, Vlad from Anthony Frost, hell, even Irene my yoga teacher who doesn’t go out! It seemed like all corners of the Bucharest cultural underground came together to support them and brought their friends, too. It was beautiful.

Overall, the festival’s strong point has been its social factor rather than its curatorial music choices. They made a very inspired choice in terms of venue and somehow managed to create an incredibly laid-back environment where dressed-down hipsters, their parents and kids could all come, play in the sand and listen to some tunes among the Ailanthus altissimas.

Even if they just wanted to make a statement, they couldn’t have found a more appropriate and on theme venue than the Uranus Garden. The Rahova-Uranus area is a tricky, yet fascinating area: located somewhat central, about three tram stops from Piața Unirii, it has the authentic gypsy ghetto feel one might expect from a visit to Bucharest. However, the neighborhood is whithin walking distance from Casa Poporului and the Contemporary Art Museum and features an assortment of beautiful, if decaying old houses, many relics of ’20s and ’30s modernism, alongside Neo-Romanian structures. The area is also home of the vibrant flower market, one of my favorite places in Bucharest and probably the last safe haven for the now-extinct stray dogs.

The neighborhood is also weirdly half-gentrified, with the Tranzit art center nearby and The Ark venue, which has hosted many Rokolectiv parties, right across the street from the market. It might seem scary and exotic at first, but once you have your first visit you see it more like an archaeological site, a living relic rather than a truly dangerous area.

Stepping inside the festival grounds, you instantly feel like you left Bucharest for some unknown vacation territory. The courtyard surrounded by tall brick walls hosts a surprisingly large area; it features a large old water tower, centered by sprawling trees of heaven, asphalt, as well as a generous sand pit.

The organizers made a point of not only creating a concert area, but turning the venue into an oversized vacationing facility: there were little artisanal stands, activities ranging from a photo booths to gong playing, a food truck with a large bar area, as well as an entire lounge wing complete with some of the most comfortable bean bags I ever experienced. It looked like the ideal alternative day care.

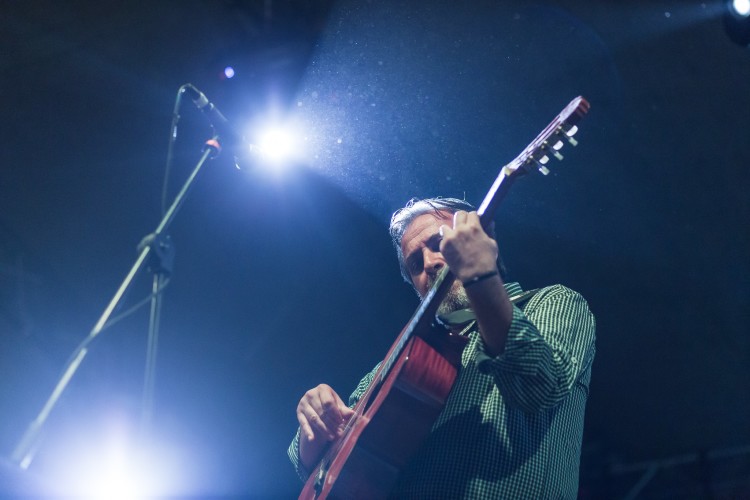

The festival started off with local veterans DJ/producers Khidja, performing live for the first time. Having started DJing around 15 years ago as teens, Rusu and Flore have become household names in Bucharest. Their recent oriental-infused electronic productions have garnered them some much-deserved international attention. Their choice of presenting a live set felt like the most natural progression for them. Carving a live set is always a challenging task for producers; they made the clever choice of inviting the musicians they collaborate with in the studio on stage. However, their still experimental live stage, combined with the challenging timing of the opening slot made for a less riveting performance. They would have probably made more of an impression after dark, easing people into club mode.

Even after their set, people seemed more eager to socialize or just try and spot their friends and local celebrities rather than get ready for another live set, especially since it was still pretty light out at 9pm. This was actually the beauty of the venue: if you just wanted to have a drink and catch up with people, there was plenty of space for doing so, without having the music on too loud. Unlike a regular setting, you could easily walk a little further away from the stage and keep chatting without going deaf or interrupting the show. And if you really felt like the music was pumping, you could just get closer to the stage and take it all in on the Funktion One. This was also due to the strange geography of the spot, as the volume seemed to shift quite a bit, taking the sound booth as a reference point.

The Egyptian Maurice Louca Trio quickly took to the stage, delivering an energetic performance blending melodic Arabic motifs and RIO dissonance with pounding live drums, bass and electronics. The crowd quickly gathered in front of the stage, jumping, headbanging or simply nodding. It was an intriguing display of forces that teased melody while refusing to coagulate into proper dance music. They seemed like angry free jazz-rockers who played at weddings. Despite their best efforts, the crowd was still pretty scattered and waiting for something more exciting to happen.

Earlier in the evening, I spotted a mysterious golden figure from behind; seeing the outrageous head-to-toe lame getup, complete with head gear, I thought it belonged to beloved performer and queer figure Palomus.

Soon after I got to learn it was African-American musician, Idris Ackamoor, the leader of Idris Ackamoor and the Pyramids. In my defense, his long head scarf and crossed arms made him as golden as an Oscar statuette.

The charismatic frontman and his band brought a much needed grooviness to the evening with their enthusiastic funky jazz. The crowd around the stage grew thicker and people finally started dancing: the long-awaited party was finally taking place! The band delivered a dose of feel-good grooviness, complete with funny shout-outs and anecdotes that got pretty much everyone moving.

By the time their set was over, we felt like it ended way too soon and we could have kept dancing for hours. Luckily the party moved to Control Club, where the aforementioned Booty Carrell was working his magic to a room of very eager dancers. There were about 2-300 people, at best; this made for a more intimate atmosphere, as the people tended to spread out and try out larger, more elaborate moves, channeling their inner harem belly dancer through their hands or going into full interpretive territory.

He was followed by Andy Votell, the man behind the Finders Keepers label, who managed to keep the same kind of energy until the early hours of the morning.

Saturday was probably my favorite day; a slight change in temperature made the afternoon heat easier to bear- if, on the first night, it felt like the garden was trapping all the warmth accumulated during the day to a suffocating effect, now the 6pm temperature was surprisingly bearable. This probably contributed to making the RBMA interview with Rabih Beaini and Vincent Moon an actually highly enjoyable discussion in the sand, together with the newly added shade sheet. It finally started feeling like the coolest garden around.

The evening debuted with a last-minute addition to the line up, the improv trio Miron/Coțac/Stanciu, lead by experimental violinist Diana Miron, alongside Daniel Stanciu also known as Minus and Laurențiu Coțac. All three also take part in the free-form local improv project PFA Orchestra, initiated by Iancu Dumitrescu and Anamaria Avram.

Their set oscillated between pure noisyness and Diamanda Galas vocal improvisations, clocking in just over 30 minutes. While their sonic exploits are certainly interesting, their experimental set was rather disruptive, taking us out of the laidback festival feel. I’m all for adventurous curatorial moves and I do condone promoting local artists, but in this case it was quite the unfortunately, bordering on being a filler act, rather out of place.

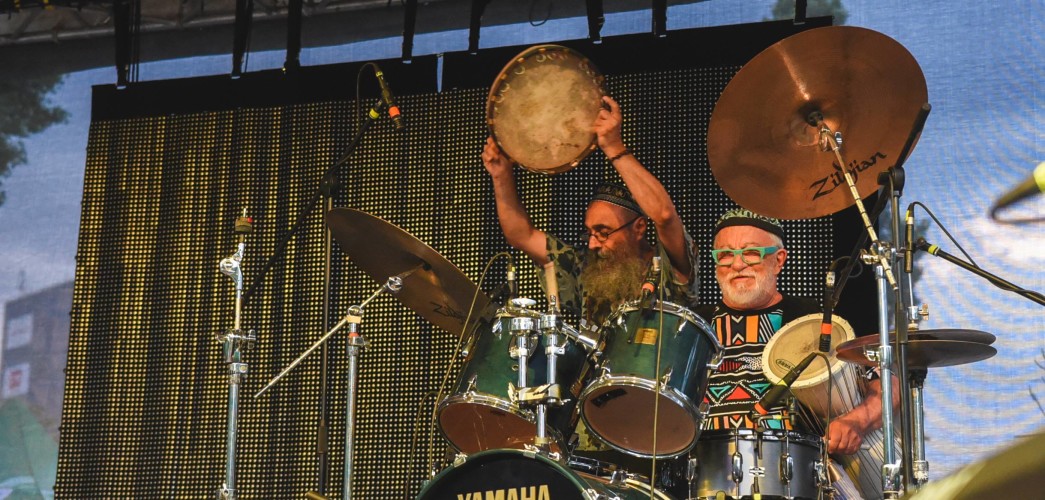

Things started to shape up with the collaborative effort of local Armenian jazz hero, Harry Tavitian and legendary Turkish percussionist, Okay Temiz. The two musicians have met before some 20 years ago, when Okay invited Harry on tour as part of a project with musicians from all the corners of the Black Sea.

It was quite moving to watch the two veterans at play, providing some superb improvisations. The set was built around Harry’s baroque piano harmonies, that rolled and lulled with intricate byzantine melodies. He was leading the session, his motifs being almost overpowering at times. I haven’t seen Harry play since high school, but his music was both intriguing yet strangely familiar.

Okay was adding beautiful percussive textures to Harry’s themes, building on his playing while letting him take the lead. I could have spent hours watching Okay play what looked like a treasure-trove of bells and magical percussion toys, ranging from actual hardware to handmade knick knacks.

The most impressive moment was when he put his self-made Berimbau to use, this strange, very physical African instrument that looks like a bow and a round wooden bowl.

You could tell there were a lot of jazz fans in the audience, as they knew exactly when to applaud during a solo.

This was supposedly a commissioned piece, although it sounded better than anything I had heard so far during the festival.

Another last-minute change occurred in the line up, as Baba Comandant & the Mandingo Band, together with Hisham Mayet, just announced they missed their flight due to incresead security measures as the Brussels airport. The organizers were quick enough to turn this setback into an advantage, programming Rabih Beaini and Vincent Moon’s AV live show during the slot.

While this crisis was averted, a literal storm was brewing on the horizon; the slight breeze we’ve been enjoying all day turned into actual wind, together with dark clouds and thunder. Taking a gamble with the elements, they decided to set up the stage anyway.

As nightfall started to settle in, it was finally dark enough for the performance; a large screen was installed in front of the stage, while the performers were sheltered under a canopy. The darkness grew stronger and the immersive journey began, blending Amazonian Ayahuasca ceremonies and whirling Dervishes in long stream of ritualistic behaviour. It was like the Alejandro Jodorowski version of Koyaanisqatsi.

Outside, the sky looked more and more menacing, developing into a full blown thunderstorm. The audience was too entranced by the fascinating spectacle of sound and images to worry about the storm. In one can only be called a magical cosmic play, as the show reached its climax, a large, glowing thunder appeared from behind the screen; at the exact same moment, a display of fireworks erupted on the left corner of the horizon from the direction of the wedding ballroom nearby, creating a rare, glorious coincidence in a moment of gracious accidental stage design. These ambient sounds merged with the performance seamlessly, making it hard to distinguish which was which.

Scattered rain drops started reaching the seated audience, but that didn’t seem to break their concentration. By the time Dan Armeanca and his band reached the stage, the rain had started to pour; this only motivated the audience more, who, faced with this inconvenient, simply decided to dance it off.

The growing storm did not deter the audience, but managed to add a layer of extra drama to Armeanca’s tortured songs about longing and heartache, turning the stage into a collective form of emotional exorcism.

Armeanca, considered the grandfather of modern manele, proved to be a talented and highly entertaining performer, constantly addressing his audience and engaging with them. He even asked to have the lights shun on the crowd dancing despite the rain, in total abandon. It was one of those very intense moments you had to be fully part of in order to truly appreciate them.

By the time his set ended, the rain had died down and the crowd headed to Control Club, intrigued by Rabih Beaini’s powerful performance.

After a warm up by the ever-curious Scoro, Rabih began to work his magic. His set was a true masterclass in DJing, especially for all the young bucks trying to do the whole oriental-techno thing – those kids got schooled.

I’m usually less attracted by overly dark dance music, but in his case it wasn’t the pumping or punishing kind, but a highly esoteric, trance-like experience that felt more like a shared ritual than a party. Yes, he was delivering those rough, hard beats at a speedy bpm, yet he was cutting them with gongs, cymbals, chimes and weird sound scapes, in moments of beatless near-silence. Unlike the regular techno formula of constant beats with occasional ambient overlays or breaf pauses, his were true meditative interludes, with breaks of Cambodian flat gongs that lasted up to two minutes. He was weaving and unweaving those sounds, slowly seeping in and out or rhythm in hypnotizing moments.

This experimental approach was weeding out the crowd, leaving only the most dedicated listeners, who were dancing feverishly, possessed.

His set ended with general applause and fans hungry for more. Taking over around 4 am, Belgian digger DJ sofa had quite the shoes to fill. His cheeky selections of ’60s Turkish psychedelia and other equally obscure world music gems were unfortunately too much on the soft side for the hardcore remaining dancers.

Sunday rolled in with breezy ease, bearing the fresh after rain scent; by now, the Uranus Garden had a vague sense of familiarity and walking in felt like stepping into an extended family reunion, with new and renewed friendships. People were exchanging smiles with fellow dancers from the night before or making new bonds on the sandy dancefloor.

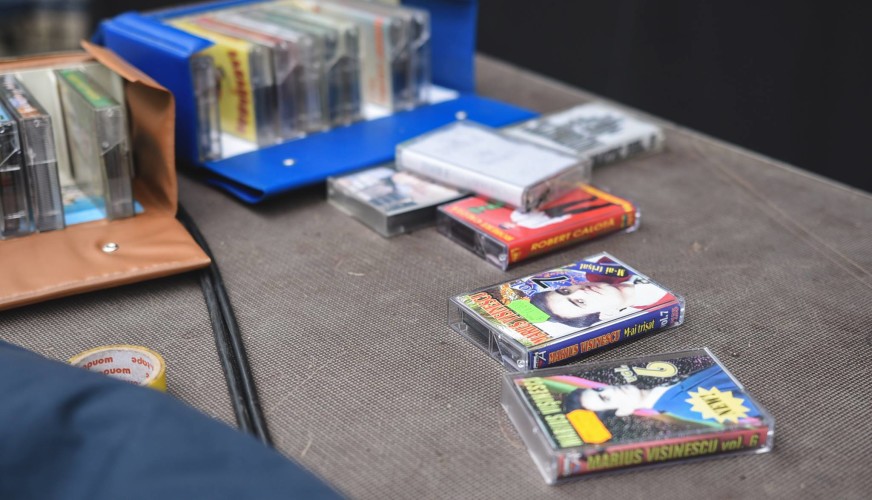

The early evening was soundtracked by a cassette tape DJ set from Paradaiz Tape Maşina, playing a selection of fun, tongue-n-cheek proto manele and other obscure ’90s findings. The naïve and equally risqué lyrics of those songs, accompanied by cheap electronics made for a highly entertaining dance party whose default mode was dancing and laughing at the same time. The song I remember when I most went something like “Sex, sex / Let’s have sex/ Sex, sex, sex”, sung in a high-pitched feminine falsetto, in a moment of pure camp innocence.

My German friend Booty Carell was sporting a face-large grin and jumping around in the sand front row with a pretty willowy lady. He looked like the happiest trooper in the soundbox, his enthusiasm rivaled only by the handful of kids running around and dancing.

As the sun started to set, the beloved Raze de Soare started their concert. The duo, featuring Future Nuggets label owner Ion Dumitrescu on electronics, queer night Muva Cosima von Bülow on vocals and joined live by the mysterious Matteo Islandezu at base started as a one-off cover band, reinterpreting four of the song from infamous ’90s proto-manele band Albatros, written by Marian Lepadatu. Due to their unexpected success and popular demand, their repertoire incorporated other famous manele standards.

The moment they started setting up on stage, the entire garden migrated towards the front, quickly filling the space. Cosima, with her tall, statuesque figure, looked like a beautiful mermaid in the glowing sunset. They were welcomed with enthusiastic cheering and instant dancing. The crowd seemed to go wild at every other song they played, whistling and singing along. It was a very intense, emotional set. When Cosima announced the fan favorite, “Regina tristeții”, the crowd went wild.

But what was most endearing was seeing not only the regular hip crowd, but a healthy number of people from the neighborhood in the crowd, who were actually the most fun of the group, always dancing up front and sporting the moves to put everyone else to shame. There were a lot of kids, but also adults and even entire families who came out to see the show, enjoying the modern, electronic take on their beloved songs. It was only natural for the organizers to let them in, considering the last day of the festival was a large exercise in appropriating gypsy culture. However, from what Cosmin Țapu told me, letting the neighborhood kids join in at paying events in the area is sort of a tradition, Rokolectiv practicing it when it was taking place at The Ark, back in 2008.

By the time Novomatic & Marius Vișinescu, another ’90s band unearthed by Paradaiz, took to the stage, the garden was in the midst of a full blown neighborhood party- kids were dancing with their parents, girls were going barefoot and guys were losing their shirts. The energetic prot-pop group sent sparks off in the air, having everyone join in the fun.

Of course, there were also jaded by-standers, even amongst the most avid fans, complaining about “too much manele” or the music evoking olfactory visions of sizzling meats, the epitome of culture populaire in Romania. While the quality of the music was debateable, it was best enjoyed for what it was rather than trying to turn it into a form of hight art statement. Ultimately, we’re talking about a relic from the early ’90s seaside restaurants, in the troubled post-Communist years, highly linked to the working class.

No matter what the skeptics said, the band’s enthusiasm was absolutely contagious and whoever didn’t go join the fun for at least a couple of tracks was nothing but a bitter sourpuss. As Booty put it, when talking about the popularity of manele abroad, “the only people who don’t enjoy this kind of music are jerks”.

One could say the festival went off with a bang.

At the end of those three action-packed days, the thing that stays with me most is the garden; they somehow managed to create the most relaxed and friendly festival atmosphere I have ever experienced. The venue was small enough to feel intimate, yet roomy. It was the perfect hangout scenario. Also, it seemed like everyone set aside their differences and put their nicer selves forward.

The festival seemed especially designed for young parents to take their kids out for some music and hipsters to drag their elders to a live show they would actually enjoy. It gave the guys the perfect excuse to dust off their oversized ’80s shirts that were just a bit too loud to wear and girls the opportunity to look like they just came back from a ’70s bra-burning party. It was a lesbian’s field day- I don’t think I’ve ever seen more nipple and side boob together.

Despite the many line up changes, the musical experience was rich and compelling; I believe it worked perfectly fine even without the headliners and could have drawn a similarly-sized crowd had they decided to eliminate those from the line up initially.

Personally, I could have gone for a less strictly academic and more eclectic, cross-genre approach, but I’m sure the next editions would grow more adventurous.

Outernational Days turned out to be the only event this year that made me feel like I was taking a trip to some new, exotic place outside the city – it was almost a holiday, and a pretty darn good one.

Outernational Days was at Uranus Garden and Control Club between 1-3 July 2016.

POSTED BY

Andra Nikolayi

Andra "Amber" Nikolayi is a sound artist and researcher. They did a masters on the use language in experimental music at the Art History and Aesthetics department of Université Paris 8 and received ...

andranikolayi.tumblr.com

Comments are closed here.