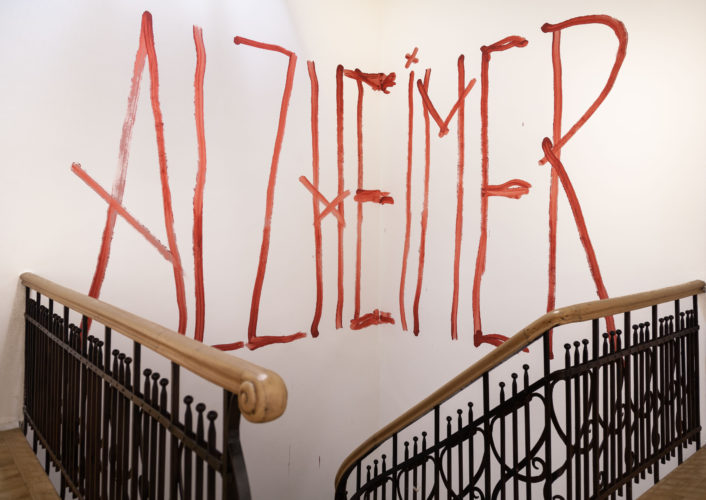

Alzheimer, the latest exhibition featuring Călin Dan, which took place at /SAC between the 27th of October and the 25th of January, curated by Ruxandra Demetrescu & Silviu Pădurariu, seemed to preach (yet again) to the hyper-intellectualism of a generation that made a mark in an incipient phase of a national sociopolitical transition. The artist’s works, relative to his recent productions (his part in Fricțiuni Tensiuni Controverse Conviețuiri Coexistențe at /SAC, 2019, and in Serving Art Again, a compressed retrospective of the duo-trio-duo subREAL at Art Encounters 2019 in Timișoara, and his most recent solo show Alzheimer) are like an unbroken flow tracing a (re)capitulation of a personal history, while at the same time running completely parallel to the pressing concerns of the contemporary Romanian art scene. But what does such a path mean today, when relevant contemporary art spaces are falling apart (e.g. The Paintbrush Factory) or going nomad (e.g. tranzit Bucharest), and how do such individual/very slightly collective recuperations relate to a context that seems to be crumbling under its own weight?

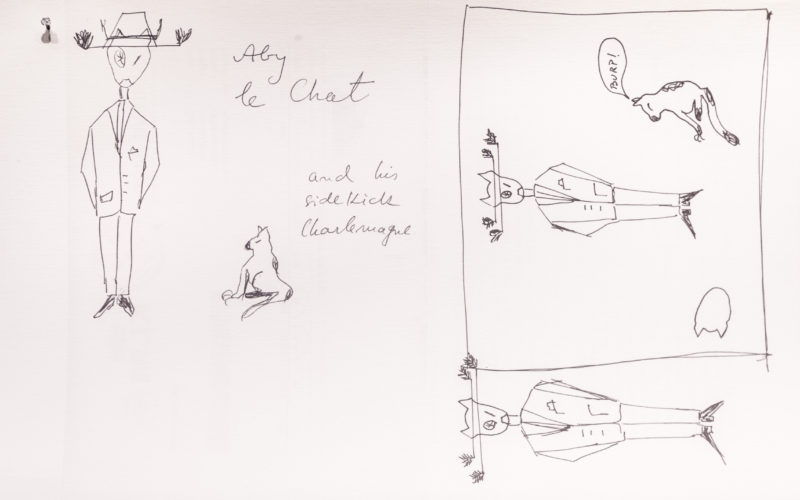

The cornerstone of Alzheimer is memory work, with the additional critical analytical and pedagogical parts. History-looking-towards-precedence/history-looking-towards-a-precedent serves to (re)frame certain aspects that consciously point towards the past, towards “something coming in from behind” rather than “something that can be seen up ahead.” The first and most obvious aspect, manifestly critical due to its recognizability, concerns the belonging to a not-quite-recent history populated by the “specters of visual culture,” where, between pop- and post-ness, Călin Dan showcases two polite obsessions, Aby Warburg and Marcel Duchamp, on whose shoulders he builds hyper-usable hybrid anomalies, bordering between reference and doubling: the photos Stea căzătoare (Shooting star) and Nud coborând scara (Nu descendant l’escalier), together with fragments of a visual diary titled Aby Pisica Chioară și Tovarășul Său Charlemagne – o călătorie (Aby the One Eyed Cat and His Sidekick Charlemagne – a journey).

The second aspect lies in an uncertain ambivalence, in “the twofold aspect of Călin Dan – that is, the critic and the artist – living together in a sort of symbiosis in which each in turn feeds – or parasitizes? – the other, or, in other words, each becomes the other’s ghost,” as Ruxandra Demetrescu’s curatorial text reads. By showcasing three fragments from different sources, we can see that assuming and maintaining an identity can be a burden.

- house pARTY 1987, 1988, Idea Design & Print, Cluj, 2016, pp. 65, 67: “Did the house party events represent a turning points in your artistic development? C.D.: No, back then I was in a gestation period. That is, I was a cultural fetus enveloped in a fragile uterus that fed me and protected my recklessness. I didn’t really know what I wanted. The birth happened out of necessity in 1990. It was a terrible year for Romania, and that’s what prompted me to collaborate on creating subREAL and to start becoming what – I hope – I am today.” And “[…] In 1990, having practiced art criticism in a variety of ways for fifteen years, I decided that the historical moment obliged me to change something […]”

- Fotografia în Arta Contemporană. Tendințe în România, după 1989, published by UNARTE, 2006, p. 265: What made you switch from theory to art-making? C.D.: I was never really a theorist. I only used theory when I found the subject I needed to write about boring. I was a disciplined soldier who wrote about Romanian visual arts between 1976 and 1990, way too long a time. The topic was only interesting on rare occasions, but the actual activity was, at least for me, more fun than the alternatives (the history of old or modern Romanian art); at least I could work with living people.”

- Revista ARTA, nr. 34-35/2018, Dosar Arta Media, Îmbătrânind în „noile media” (2.0), text Călin Dan, p. 48: “I’ve written so many times (thank you, Geert Lovnik) about my failed career as a ‘new media’ artist that I will limit myself here to establishing a timeline of events and listing a series of names.”

Two other works, Scaunpumnal (Daggerchair) and Părăsit (Leftboy) raise, in relation to the artist’s explanatory statements, further questions about the contextual connections they generate. “A chair […] sculpture,” the result of “a passion for architecture and design” and termed “a very beautiful object,” is a binary manifestation of human sexuality. “The hermaphrodite chair” is referred to as a “place of meditation.” However, the artist’s discourse around this object focuses rather on its formal elements, the way in which they work together to offer some kind of intrinsic value. He then speculates on the potential gender perspectives gained from interacting with the work (which is not allowed in the exhibition).

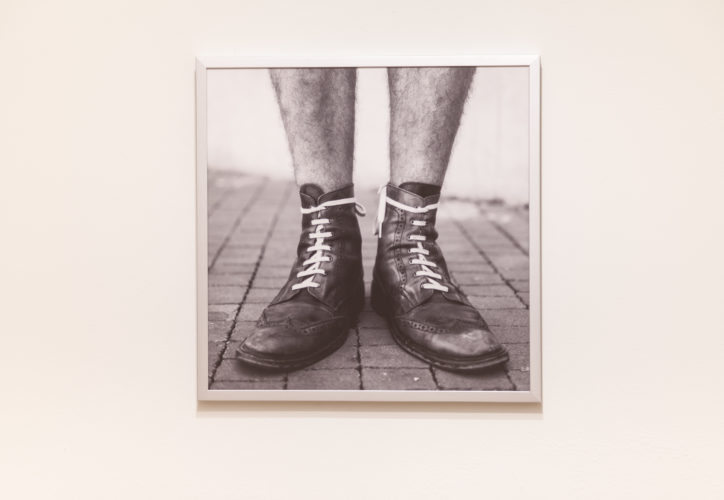

In contrast to Daggerchair, the photo Părăsit seems to have the power to stir a justified generational conflict, one that existed in the past in other cultural areas too. We see therefore, in the artist’s own words, “a very simple visual parable that came out of an accident. One morning, being hungover, I put my shoes on backwards without realizing, and I was absolutely fascinated by the coherence of this confusion.” Of course, the accident, with the added triviality of the context, could generate an entire network of meanings, masked by the surface appearance. However, in this case, it seems the work lacks the necessary coherence.

The work Afumare (Smoking) is the unofficial centerpiece of the exhibition. It is a still from a video work that shows two characters, one played by the artist Ion Grigorescu, naked, gaunt, frail, who is subjected to an investigation by the second character, Călin Dan, who is smoking a cigar. This might possibly be self-irony, a reference to the latter’s high institutional position, but not enough clarification is given. “I asked I.G. to play my father,” says the artist, apparently dispelling any connection to the present. Given that the artist’s discourse was lacking, I had a dialogue with Grigorescu himself (reproduced below), which did not necessarily clear up the situation, but maybe at least offered the hope of opposing the issue of generational gaps and of bringing together and consolidating the active members on the Romanian scene.

Ștefan Simion: When I visited the exhibition, what struck me first were the works that you were part of (Atârnare Alb, Atârnare Negru, Mers, and Afumare). I was curious how you started collaborating on these works together with Călin Dan and whether you’d worked with him before…

Ion Grigorescu: We didn’t collaborate on this one [i.e. Afumare], but on the other two. We did try a written collaboration once – I don’t know if Călin would want me to talk about it. It’s an abandoned project. It didn’t work out. But we tried. Regarding Afumare, all he did was give me a call and ask me if I could help him. He vaguely mentioned that it would be something about his father. I didn’t ask any questions, like what’s the deal with the father, whether he exists or not, and so on. I just did what I was told. We also worked together a few times when he was the director of the Soros Center. One day we met around the corner at the University. He had his bike, or I had my bike, or we both had our bikes. I can’t remember exactly, but there were some bikes involved. This was in the ’90s. And he said:“I’m done helping others. I want to start working on myself.” That’s when any prospect of collaboration vanished. We later met in Lisbon, in 2005. He was exhibiting with Iosif Kiraly, each with his own stuff. He was telling me I was their teacher from a different generation. Which is true. I’m from the ’70s and he’s from the ’80s, thought I don’t know how much art he was making back then. He was working with ARTA Magazine, which he took over after the fall of the [communist] regime. And that was that. We met more times than we collaborated. As for the works seen here, I was only the actor.

I understand that this one [Afumare] is actually from a film…

No idea. If they decided to film that’s their business. I’m not concerned with property. You’re free to do what you want, I won’t stand in your way. What do you find so odd about this collaboration though?

Not odd. More like intriguing. Phrases like “the ’70s generation” or “the ’80s generation” are well-known in art history. I was curious if you find such generational divides important or if there is something more like a continuity…

To be honest I was never too concerned with that stuff. But I never really encountered neatly separated generations. There are so many artists working in the middle. There are artists like Baba’s students who maybe use such divisions for themselves but who you couldn’t place into generations from the outside. Art critics focused especially on recuperating the ’80s generation. First it was the poets and writers who popularized the term, and then the visual artists were lumped in as well, given also the appearance of postmodernism. But I don’t think the Romanian ’80s generation really corresponds to generations abroad. Here it really stood out, especially in literature, because it accused the earlier generation of sweetening their works, transfiguring them to make them pretty, while the others [the ’80s generation] were more raw, used strong language, and found it harder to be published, but in the end they made it. Then, regarding the ’90s generation, Ms Aurelia Mocanu organized a few exhibitions, but I didn’t find anything really remarkable. There was no longer the unopposed ’80s generation. These were just artists that became international and somewhat mimetic.

During communism there was this influence of an authority which, after the revolution, moved from the state to certain varied power structures, institutions, centers, and so on. Because there has always been a relation to authority. Do you think this is a factor that influenced the works of Romanian artists?

This authority, in my opinion, was divided. There were multiple authorities. On the one hand there was the state, which was more or less incapable of doing anything for artists, but also of imposing or preventing things. It was simply too broke. Then small influence centers started appearing, like the Soros Center, which offered a new kind of authority: that of money. The authority of money meant an authority that imposed themes and thought processes, like the uncivilized Balkan society or gender issues. In the end everyone was their own authority and everyone was against everyone else. You rarely saw a person who was not involved in this situation. Very few managed to find a gallery to exhibit in or to be able to say something abroad, even just a personal message. That’s my view. Maybe I’m wrong.

Returning to the current exhibition, there are works that openly reference well-known elements of art history. Do you think reference, that is, relating to the past, is important? Or would it be more important for a work made in the present to relate to the present?

I mean, everyone does what they can. Sure, Călin is a historian and critic. And writers of history are fleeting presences. What’s left are the works, which settle into a group of more works. For instance I kept wondering what’s with that cat [Aby the One Eyed Cat]. When I was at the opening I met Bogdan Vlăduță, who said to me, regarding the videos I was in: “Amazing! This is something I thought of too. I have a work just like it.” That’s the spirit of the age. The spirit of the age trickling down to each of us. Then he sent me a big painting with a figure doing I don’t know what, but resembling the strings moving the character. In the end we all play a part in continuing history.

I was wondering if memory plays a part in this process of integration into history…

There is a kind of surveillance-related paranoia, because, for a creator, memory is there to tap them on the shoulder and say “it’s been done already.” It has to draw their attention. Of course, there are people who don’t care. It happened to me too: When I was in high school I read a book on surrealism and it said there that it’s shameful to do something others have done before. Not in the sense of a copy, but as rehashing. What could possibly come out of that? Nothing. Certainly not something better. What could result though is an addition to something that seems incomplete. But why would you do that in the first place? Memory therefore watches over a personal kind of development. But memory also has the downside of binding you.

The discussion then began to stray from the topic (the exhibition’s text/discourse), veering towards the degree of originality in contemporary works, online archives, digitizing video works shot on film, and Hito Steyerl. Though relevant for a lot of people, the full transcript would not, unfortunately, contribute to a better understanding of this exhibition.

It seems that Alzheimer inadvertently speaks about the tension felt by a lot of people from within the local art scene. Perhaps, in a brighter future, such initiatives will be able to exist alongside other percutant voices.

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Ștefan Simion

Ștefan is an artist. He studied Romanian and English at the University of Bucharest, and is currently studying photography and video at the National University of Arts Bucharest....

Comments are closed here.