At a first thematic glance, this year’s film selection at the Bucharest International Experimental Film Festival (made by Oana Ghera, the festival’s new artistic director, and associate curator Flavia Dima) is at least marginally connected to the idea of pandemic, through politically engaged films in which the potential fate of humanity passes through a dystopian or utopian lens. It might therefore seem that the films grouped under Sublime Bodies, perhaps the most consistent and stimulating section in the competition, would clash with all the rest, as it focuses instead on corporeality and gender representation. On the other hand, I see no better time to talk about how we see our bodies than this insular year in which we have done nothing but reject and repudiate it, removing or hiding it from the gaze of others. Within this paradigm, indebted to Cartesian dualism, bodies are both performative and evocative.

Four performances – floral, muscular, cabalistic, robotic

The first film in the program, Amaryllis (d. Jayne Parker), is a deconceptualization of beauty itself – the aesthetic perspective of an implicitly voyeuristic gaze towards a flower carrying out its light ritual has something fetishizing about it. It is the alchemical ambition of discovering the most intense and lascivious red possible, associated by the viewer with sensuality, through the medium of film (an objective lens, incapable of perceiving and distinguishing beauty). It is also about a spectacle independent of the way in which the camera perceives the phenomenon, an aesthetic anomaly: this wonderful red flower sometimes turns white, changing its aspect completely. This kind of beatification, seen together with the other films in the program, implicitly references the idea of performance, an aesthetic one-man show that the flower puts on for those patient enough to watch it; it is the reward of erotic expectation. It comes as no surprise that it only unveils itself at the very end.

Performativity is also a topic in Arnold Schwarzenegger, The Art of Bodybuilding (1977-2019) (d. Babeth M. VanLoo), where the director uses a short interview with Schwarzenegger taken at the 1970s Mr. Olympia competition. Initially conceived as an installation, the document does not feel dated. On the contrary, it invites one to an a posteriori reflection on Schwarzenegger’s histrionic career (from bodybuilder to macho movie actor, Terminator, and politician). The interview is lively, because, on the one hand, it connects to certain emerging discussions around representations of the male body (through Leni Riefenstahl’s movies and Michelangelo’s sculptures), but it also briefly explains how bodybuilders view their bodies. Schwarzenegger uses all kinds of metaphors associated with manual work (“you become an artist and you’re working on your own body like an artist works on a piece of sculpture”). He also mentions the symbolism of the gesture it is not enough to perform a physical routine and sculpt your body, you also have to show it to the world, by taking part in competitions and posing – returning to the idea of performativity.

A Passage (d. Ann Oren) arrives at performance from the opposite angle, through the fetish of hearing and being heard – the routing of a foley artist, always having a quasi-mystical, if not absurd quality (to try to reproduce a natural sound artificially often involves making use of unusual objects). Here we have the image of a galloping horse, which the artist follows with his gaze and, at the same time, produces it acoustically – he uses his body as a counterpart reveling in an altar of fabrics (sand, textile, leather). From the ecstasy of hearing his perfect sounds, he transforms into a horse, swinging his tail through the living room, flirting with the camera, and dancing. In the end it is a matter of perspective, as you do not know who is following who (an idea Oren mentioned in the festival’s panel too, when he presented his film as a loop in an installation, and, through repetition, the horse came to look the artist in the eye).

In this category we also have Michael Portnoy’s Progressive Touch, an atypical short straddling the boundaries between video game, music video, porno, and musical. In it, multiple real life dance couples (heteronormative and homosexual) act out a non-narrative mating dance that seems to be a kind of sexual robotics (for instance, the tip of a penis that vibrates in tandem with the bass). Sometimes the movements are reminiscent of Michael Jackson’s Thriller, and, as arbitrary as the connection might be, the work is an experiment that deterritorializes sexuality as we know it, brings it to a space and movement where it becomes something else – no longer a power struggle but a discontinuous ritual of celebrating one’s own body. At the same time, at the antipode of this relaxation, in Eadem Cuts: The Same Skin, Nina Hopf narrates the experience of a transition from female to male and how liberating the experience of feeling at peace with one’s own body was for the subject. The film is invaded by VHS tapes and xerox prints with his body before and after. An almost tactile, palpable relation forms between spectator and the person stripping in front of the camera.

In the mirror – A Demonstration and Seismic Form – vivisecting the world

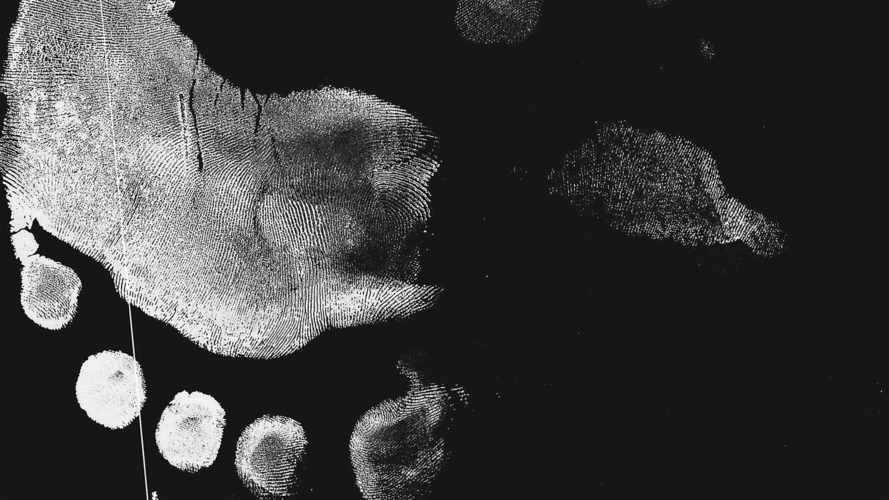

A Demonstration (d. Beny Wagner and Sasha Litvintseva) and Seismic Form (d. Antoinette Zwirchmayr) are the most abstract movies in the bunch and, mirroring each other, offer two ways of dissecting the world’s innards. The first investigates monstrous forms that still have aesthetic value (paintings, sculptures, natural phenomena, etc.), referencing the ways natural scientists would classify things in the world, while Seismic Form is broken up into a number of chapters illustrating tectonic movements (“we can no longer observe the stars or the sky, but we must observe the underground deities that endanger the fall”) and plumbing the depths (for example through an aesthetic reconstruction of the city of Pompeii, placed in metaphysical territory). Here the sublime body is nature itself, which is constantly changing. Each new layer adds a little more mystery to the world. The impersonal voice-over in A Demonstration tells us that the Latin root of “monster” means to reveal, to show. The film’s demonstration: an overlap of a huge library and a thick forest, followed by revealing the inside of bodies (muscle, flesh, blood, “with each new cut, a new monster came out”). How is it that art, so ethereal and, in a sense, physically unquantifiable, almost like fog, is born from the mind of “monstrous” bodies? For so many centuries, the philosophical connection between body (contagious, ugly, fleeting, perishable) and the ineffable spirit was not allowed or dared; they were in permanent schism. A Demonstration and Seismic Form show that not only are they one and the same, but also that the fact that everything becomes ash in the end does not take away from the beauty they leave behind.

As ever, the Sublime Bodies thematic program invites new perspectives or additions to previous philosophical perspectives on the beauty of the body, offering all sorts of variables for how we can still recognize or quantify it today. However, in none of the short films is beauty something completely palpable, with implicit physicality, but comes from an experience either aesthetically or politically mediated – making it exclusively a personal and intersubjective currency. After all, the very title “sublime bodies” designates a paradox – is it a physical or ideational perfection of bodies? Are our ephemeral bodies carrying the sublime?

Translated by Rareș Grozea

POSTED BY

Georgiana Mușat

Georgiana Mușat is a film critic. She writes form Films in Frame, FILM, Eye For Film, Acoperișul de Sticlă. She follows a lot of meta-cinema and is currently writing her dissertation on female robo...

Comments are closed here.