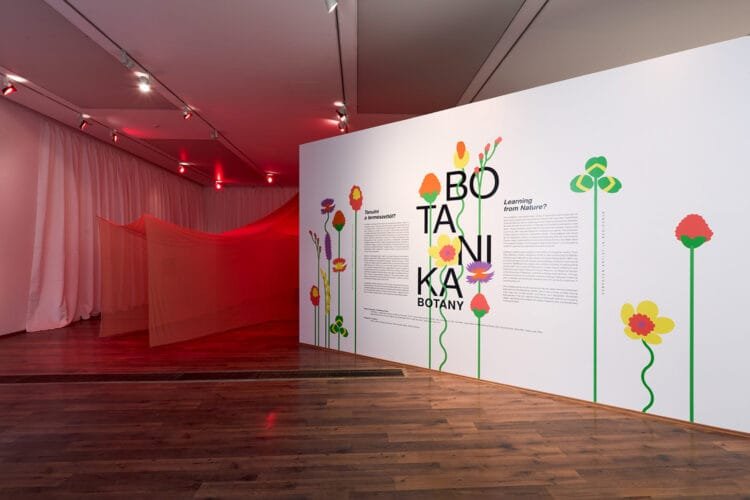

Can humans truly learn from nature without subsuming it under the language and structure of their own making? Is it possible to step outside the constraints of human perception and knowledge to understand the logic of the non-human? Or is any such attempt destined to reflect our own anthropocentric desires? Even as we attempt to engage with it on its own terms, the very act of interpretation inevitably bends nature into human contours. These are not just speculative meditations but deeply practical and urgent questions in an age of environmental collapse, where the lines between nature and culture have grown increasingly entangled. The exhibition “Botany: Learning from Nature” opened at the end of last year at MODEM Center for Modern and Contemporary Art in Debrecen confronts these challenges through an assemblage of artworks that do not seek answers as much as they generate possibilities.

In a way this exhibition arises from Debrecen’s historical legacy as a center for botanical research. From the first Hungarian herbarium compiled by Péter Méliusz Juhász in 1578 to Sámuel Diószegi and Mihály Fazekas’ Hungarian Herbal Book in 1807, the city has long been a locus of inquiry into the field of natural sciences. It’s also the culmination of the 2024 Debrecen International Art Residency (DAIR), a two-week intensive program held during the summer of 2024. Bringing together artists, architects, and designers, the residency featured not only artistic and research activities but also a series of public lectures and discussions, creating opportunities for local audiences to participate in dialogues about how cultural actors can contribute to reshaping our understanding of nature. Building on this heritage, ten newly commissioned works on display provide fertile ground for interdisciplinary exploration, while also drawing connections between historical botanical knowledge and contemporary ecological concerns, using the context of Debrecen’s surrounding landscapes — like the University of Debrecen’s Botanical Garden, the Hortobágy National Park or the Reformed Collegium’s Museum and Library —, collections, and institutions as a foundation.

The exhibition, curated by Krisztián Gábor Török, Dorottya Vékony, Szabolcs Süli-Zakar, and Attila Horányi revolves around three interconnected themes: observing Anthropocene landscapes, reinterpreting natural symbolism, and engaging with speculative storytelling, through the works of Szabó Bálint (HU), CENTRALA – Małgorzata Kuciewicz & Simone De Iacobis (PL/IT), Daniel Godínez Nivón (MX/NL), Zsófia Szonja Illés (HU), Eszter Júlia Kuzma (HU), Thea Lazăr (RO), Katalin Kortmann-Járay & Karina Mendreczky (HU), Gaja Mežnarić Osole & Krater Kollektiv[1] (SI) & Ivana Papić (HR), Nóra Szabó (HU) and Dorottya Vékony (HU).

The first section, Ecological Niches, Anthropocene Landscapes, Feral Grounds focuses on how we perceive and document the overpowering changes in the natural world caused by human activity. By examining ecological niches — the optimal configurations of environmental parameters that allow species to thrive — the section places emphasis on the interplay between social and ecological factors that shape both human and non-human environments. This perspective resonates with the work of Bálint Szabó, who transforms the exhibition’s first space into a nest or womb-like sensorial experience in a sacred – red – flute complex, with sounds of rattles, bullroarers or water flutes. In doing so, Szabó’s installation Through shimmering voices they speak, goes past hierarchical structures of interpretation and offers a collective experience that mirrors the non-hierarchical logic of nature simply by placing sound in the center of our attention instead of any other visual stimulation.

Then through the lens of Anthropocene landscapes, artists invite us to consider spaces where the marks of industrialization, climate change, and ecological imbalance are etched into the environment. This tendency is evident in the works of the Krater Collective, a group of Slovenian designers, architects and ecologists, who transformed a long neglected “feral” urban space into their laboratory, perfect for exploring ecological resilience and sustainable urban modes. They work on rewilding and repurposing materials, particularly invasive plant species, to rethink the role of nature in urban regeneration. Their body of work shows that nature’s role as a subject of human inquiry is deeply tied to systems of power and domination. The desire to observe, classify, and possess the natural world—whether through botanical herbaria, taxonomic charts, or museum collections — reflects an impulse to impose order and assert control. From the colonial extraction of plants that reshaped ecosystems and economies to the introduction of invasive species during imperial expansion, the act of studying nature has often mirrored systems of exploitation. Invasive plants like Japanese knotweed underscores the complex histories of displacement and resilience encoded within ecological narratives. The knotweed, once a symbol of ecological disruption, becomes a material for paper-making and a metaphor for adaptation, and the herbariums we see on display, do not follow the traditions of the Enlightenment in showcasing the scientific categorization of plants and their fruits, but instead allow us to learn the story of a plant’s journey from its native environment to its appearance in our local ecosystem. These materials – like the product of an eri silkworm –, often dismissed as invasive or undesirable, become central to a narrative of resilience and adaptation. Unfortunately, like so many socially useful collective organisations, they are in danger of disappearing as well.

Under the same section, Kortmann-Járay Katalin and Mendreczky Karina’s Mirage shows us the fine boundaries between myth, ecological and cultural memory, and materiality while also thematizing the intersection of natural and human histories. Their installation blends agrarian figures like shepherds, mayflies and wheat fields with a fictional flora and fauna all covered in shifting sands, mimicking the shimmering heat and mirages of the Hortobágy. The sand, constantly in motion, captures the nature of memory and the ways landscapes themselves seem to dissolve and reform under human intervention. At the same time, the scale of the installation – also reminiscent of the vastness of the Hortobágy – occupies a perhaps disproportionately large portion of the exhibition space, somewhat disrupting the overall flow of the exhibition’s conceptual narrative, despite the view itself being captivating as always. For me, in a way, Mirage reflects on the liminal spaces where natural environments meet human perception, underlining how landscapes are both shaped by and reflective of the stories we attach to them.

Another thread running through the exhibition is Metamorphoses of Natural Symbolism, which focuses on the ever evolving meaning of natural symbols. By revisiting and reimagining themes traditionally associated with plants, animals, and landscapes artists like Eszter Júlia Kuzma, Daniel Godínez Nivón or the Centrala Architects’ woodwork Meteorici confronts us to think about how cultural and historical associations with nature might shift in light of contemporary ecological realities.

The question of how humans have historically instrumentalized nature while also being shaped by it is particularly present in Kuzma Eszter Júlia’s work, The Touch of Innocence. Her hand-embroidered textile tent draws inspiration from regional folk traditions, including the wild carrot motif, a plant steeped in regional mythology, as a site of resacralization and feminine expression in the textiles of Vojvodina and Moldova. Kuzma not only foregrounds the feminine labor and knowledge embedded in these practices but also interrogates the ways in which symbols of purity, modesty, and fertility have been constructed across cultures. By juxtaposing everyday materials – like a white lace – with ritualistic gestures – a red lamp in the middle of the installation that turns red by the touch of a visitor’s hand –, her work transforms the familiar into something charged with a spiritual tone.

If I may admit, among all the works, the Mexican artist and cultural researcher, Daniel Godínez Nivón’s The Night Will Come resonated with me the most. The Night Will Come is a video installation that layers storytelling, music, and moving images inspired by the maguey plant and its pollinators, the magueyero bat’s nocturnal dance. The haunting love ballad composed for the work, performed by descendants of indigenous tlachiqueros, becomes a weeping song for the ruptures caused by the displacement of the maguey plant from its native ecosystem. The work not only reflects on the ecological displacements caused by colonial plant collection – and showing the other side of a story previously told by the Krater Collective, since the Debrecen Botanical Garden itself has a maguey plant – but also acknowledges the profound symbol of interdependence, and questions the role of botanical gardens and other institutions in preserving nature while perpetuating disconnection.

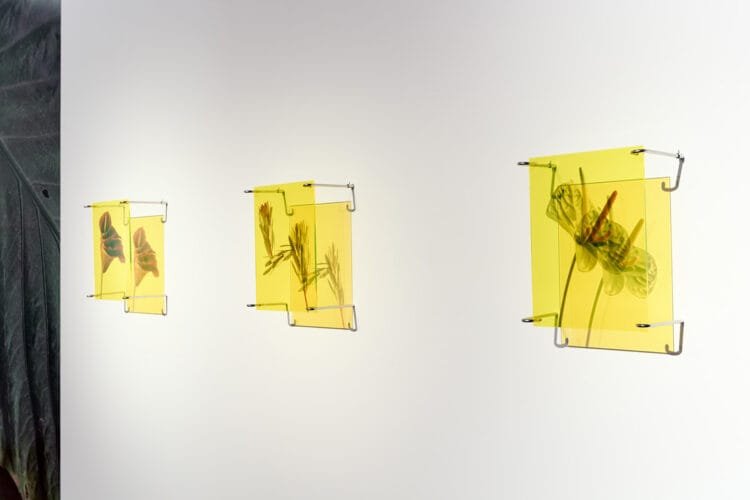

At last the works of Dorottya Vékony, Nóra Szabó and Thea Lazar, in the section of Speculative Organisms and Econarratives shows us that imagining alternate realities can open pathways to grasp the complexities of ecological change. The works grouped under this theme display speculative futures and a true desire to learn from nature, to address the challenges of coexisting with a rapidly changing environment, while also confronting the unknown. For example Dorottya Vékony once again touches on a new aspect of fertility, — this time in nature — in her installation Extended Blooming she envisions genetically modified flowers designed to attract pollinators in an alternate world defined by ecological collapse. Her hyper-engineered flowers at first glance can seem scientifically accurate but they are the creatures of the artist nonetheless. Looking at their brightly coloured shadows on the wall, right behind the plexiglass as we wonder about the limits and imprints of human interventions in the foreseeable future.

The exhibition “Botany: Learning from Nature” returns us to the questions it began with: can humans truly engage with nature without imposing their own frameworks? By presenting works that interlinks ecological histories, cultural memory, and speculative futures, the exhibition suggests that the key lies not in mastering or classifying nature but in learning to listen, and it demonstrates that such learning requires not domination but humility and an ability to navigate the uncertainties.

[1]members of the collective are Amadeja Smrekar, Altan Jurca Avci, Andrej Koruza, Anamari Hrup, Danica Sretenović, Edern Haushofer, Eva Jera Hanžek, Juan José López Díez, Louisa Selleret, Maša Cvetko, Paulin Liogier, Primož Turnšek, Rok Oblak, Sebastjan Kovač

POSTED BY

Gyöngyvirág Agócs

Gyöngyvirág Agócs is a Budapest-based curator, FKSE member, and researcher with a background in sociology and art theory. She is currently pursuing an MA in the Design and Visual Arts Education pro...

Comments are closed here.