Although restricted, private collecting was not banned in East European countries under Communism, and has now been enjoying a spectacular revival, in some of the countries from as early as the 1980s onwards. Whilst the current economic crisis has cut short several aspects of this development, other features of the private engagement with contemporary art have actually been strengthened. First, as the crisis hits the public sphere, such as museums, state art awards and prizes likewise, and in some cases even stronger than the private sphere, in numerous countries more choices and tasks have opened to private collectors and institutional schemes of the art market. Second, the crisis has sharpened the need in each of these relatively small states with clear limitations of the national art markets, to expand internationally, making the elite of private collectors and privately-run museums recently internationally more competitive than before 2008. Third, with the crisis and other reasons pushing politics and official cultural representation in quite a few East European countries towards conservative, nationalistic values, the responsibility of private actors has grown to help articulate universal and critical messages of contemporary art; more and more private museums, awards, schemes of patronage are taking over functions of public discourse, and act on behalf of civil society.

Instead of going country by country, as the preceding lecture did, this one will proceed along a certain typology of private activities in the canonisation of contemporary art in the region, picking the examples from various countries, and comparing them with public museum patterns.

Taking over specific museum roles on purpose can be observed, for instance, in the Modern Gallery – Vass Collection, Veszprém, in Western Hungary. Comprising three neatly renovated civic buildings in the historical city centre, this museum, opened 2003, with László Vass collecting art already since the 1970s, substitutes the missing modern/contemporary art museum in the city and its vicinity as well as assuming a function nationally by focusing on international geometric and minimalist art. As in Hungary few public museums engage in collecting internationally, this stylistically well-defined programme, with acquisitions by Vass from American as much as East European artists, is a significant contribution to the national museum landscape.

A similar position is due to the Art Stations Foundation, by Grazyna Kulczyk, with a private museum in Poznan, Western Poland, opened just a year later, 2004. Located in the so-called Old Brewery, actually a brand new shopping and cultural plaza (2003), built according to plans and image dating back to the 1870s, this museum is likewise to be found in a city with no major contemporary public collection, thus fulfilling an indispensible role. Its international outreach is of no less importance, as collecting foreign art is picking up slowly and only in select museums in Poland. One of the most sizeable in East European comparison, Kulczyk’s collection calls for appreciation thirdly for a reason specific to Polish society: the focus on body art, issues of gender and sexual identity, represented in the collection by works of leading Polish and foreign artists, is taboo to many in the public in this country where conservative Catholic values are deeply rooted. Thus the permanent exhibition in the museum shares the mission of public visual education.

Attracting the public to modern and contemporary art is still a challenge in Eastern Europe where poor visual training had cemented a dominantly classical taste. Often more visitor-friendly than public museums, private institutions play a significant role in this, being motivated to invite the viewers exactly because they are privately run. Coupled with targeting tourists, this motivation often turns private museums into cultural magnets, and the merits of this vocation must be acknowledged even if the level of these exhibitions, slanting occasionally towards popular presentations, deserves criticism. In Prague, in modern and contemporary art, the private Museum Kampa is certainly a better-known reference than the few public museums active in this domain. Helped by the Municipality, collectors Jan and Meda Mladek converted an old mill in the historical city centre into their museum, opened 2001; and by integrating two other private collections, the institution has expanded its permanent presentation since. The exhibition showing positions in a specifically East European context can be seen as a significant gesture towards spreading regional cultural identity. The Society of Friends of the museum is one of the most active in the city, which may not be a praise public museums aspire to, yet this engagement of private institutions to really address a broad public, should be regarded as a virtue, particularly in Eastern Europe, where such an attitude still needs to be learnt by many in the profession.

Danubiana Art Museum near Bratislava, Slovakia, may be interpreted as partly similar in its ambitions. Set up by a Dutch private collector and a Slovak lawyer / art dealer, it opened 2000 in a beautiful building on a small artificial island in the Danube, and has recently been significantly enlarged. However, its exhibitions and the collection amassed, have rightly provoked severe criticism from various corners of the Slovak art world, underlying the danger of private institutions being exposed to serving commercial interests without strict curatorial control. Taken over in 2012 by the Municipality, for reasons related to these controversies and to financial bottlenecks, the future direction of the museum is unclear now whilst a number of its former initiatives – such as the international opening by way of exhibitions of Austrian, Hungarian, Russian and Dutch art – are worth carrying on.

Established by businessman Gábor Kovács, Kogart has experienced a somewhat similar story in Budapest. Opened 2004 in a world heritage building in the historical city centre, it soon became a lighthouse for many in the public for its well-marketed spectacular exhibitions, its fancy restaurant and socially active Friends Circle. However, co-operation with art historians and curators of acknowledged scholarly renown proved problematic immediately from the opening of the museum onwards, and the institution was drifting away from professional standards year by year. Its new collection strategy (2007), co-financed by companies and the government alike, also called for uproar by art critics and public museum directors with eventually the current crisis questioning the very existence of the museum due to the owner’s gross financial problems. No matter what the future holds for Kogart, it has certainly marked the discussion on private collecting and private institutions in Hungary over the past decade. Since the majority of experts define it as merely a conservative Salon, the responsibility of such influential private museums cannot be over-estimated: there being only few in Eastern Europe, what and how they perform, is likely to define public opinion not only about them but about private engagement at large.

Private museums may very well foster visual education by keeping a distance from established museum methods – provided the path they choose is not simply for serving media interest and financial income but rather for presenting an aesthetically well-conceptualised alternative to museum taxonomy. This true challenging of incumbent museum notions characterises Ákos Vörösváry’s private museum, named First Hungarian Vision Respository, opened 1997 in a converted mill in a rural setting just north of Lake Balaton. An avid collector since the 1970s, Vörösváry questions delineations between high and low, folk and academic art, applied and fine art, modern and contemporary, even kitsch and avant-garde. Next to these transgressions, he identifies exhibiting-making and the installing of complex groups of works (of art and non-art) as a highly creative act, as a sort of art, too. These two bold moves have rightly earned him the label of a colleague among professional curators; it is only regrettable that staying within the boundaries of Hungary and Hungarian art keep the effects of his programme nationally confined.

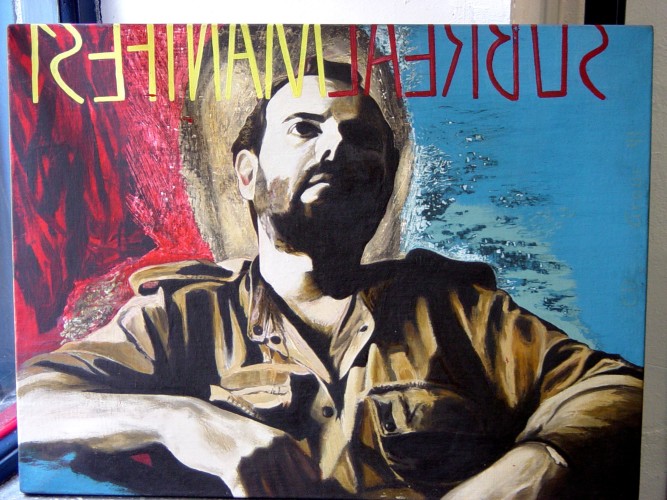

Looking for alternatives to classic museum routines can be associated with the probably best-known Croatian private collector, Marinko Sudac, too. Rooted in early avant-garde works and documents, but reaching to contemporary works, his collection, initially ex-Yugoslav, but now East European in outlook, has been presented severally, most notoriously in the port of Rijeka, aboard the vessel Seagull, Marshall J. B. Tito’s well-known ship (2011). As various conflicts hinder the erection of a building for the would-be museum, the collection was made accessible on the internet in 2009, and has been increasingly functioning as a Virtual Museum of the Avant-garde, a kind of database – with a surprisingly powerful impact on the international art world, including the Tate Modern’s newly set-up East European Acquisition Board.

This aim of making documents and works of art broadly available for research home and away, as much for general public visual education, is shared by a Hungarian-American businessman, too. György Bélai set up his Artchivum as long as two decades ago and has financed its acquisitions, IT equipment, and its staff entirely of his own pocket, spending altogether around four million Euros on the whole project so far – a sum unheard of by East European standards. Outweighing by far in importance his collection of works of art, this vocation of facilitating research on an up-to-date technical level, can be interpreted very much as a museum mission.

Rather than accumulating works and documents, staging exhibitions may also count as a substitute museum programme. DOX, Futura and Meet Factory (a hint at the former function of the building as meat processing works) are three private institutions in Prague that centre their activities mostly on exhibitions. In spite of their differences – DOX being a rather elusive, aristocratic location with entrance fees set as a social barrier, Futura operating at various locations and also building an international collection by its Italian owner, sometime in future to be shown in one of the venues, and Meet Factory, set up by infamous EU-critical artist David Cerny being best known for its active international exchange and residency programmes – their exhibition offer has become an essential component of the Prague contemporary art scene as museums and other public institutions fail to come up with a proper exhibition portfolio.

In each of the preceding three examples from Prague, the location is at least as attractive as the exhibition programme. The trend of converting industrial buildings into museums has reached East Europe too, as exemplified by MEO in Budapest (opened 2000, closed due to incompetent management 2005, with the excellent collection dispersed), Lauba in Zagreb (2011, the collection is shown chapter by chapter in a rotation), Nedbalka in Bratislava (a Guggenheim-like spiral with permanent presentation of modern and contemporary Slovak art from three private collections) as well as Winzavod and Fabrika in Moscow, two very extensive art and multi-cultural centres, each of them refurbished in the late 2000s, with spacious room for mostly temporary exhibitions, rather than a permanent presentation. Saving this architectural heritage, and filling it with culture, can also be valued as public mission, especially considering that several groups of the public are more prone to coming to these centres for the relaxed atmosphere, for the combination of art and leisure, and enjoying these locations as new urban plazas, rather than to museums that require a disciplined, ritualised behaviour.

Other buildings may also be surprisingly well made suitable for museum purposes. In Moscow, a well-known architectural landmark of the Soviet avant-garde of the 1930s, a bus garage was turned into exhibition centre by Dasha Zhukova, the London-based oligarch’s, Roman Abramovic’s partner; and the project proved, in spite of numerous and not unfounded critical remarks, successful enough for Zhukova eventually to opt for a second, larger museum plan, too. In Sofia, the likewise London-based Bulgarian businessman, Spas Roussev shows his international and Bulgarian contemporary collection permanently in a downtown hotel and a restaurant – so far mostly accessible to the local elite and visiting tourists, yet Roussev has also sponsored a number of large-scale exhibitions in public venues in Sofia. An even larger selection of contemporary Bulgarian art, from the collection of Hugo Voeten, has meanwhile been transferred to permanent presentation in Belgium, yet keeping this set-up in a specific location, this time in a converted agricultural corn silo. In St. Petersburg, the two leading private museums (Erarta and Novy Muzej), located by coincidence on the same island, occupy complete floors of former Soviet-time apartment and office blocks. In each of these cases, the twofold museum function of bringing local history to life by re-functionalising buildings of originally different purposes, and of showing contemporary art in these welcoming settings, can be played out well.

Quite a few collectors engage in art patronage. Next to his collection and the yearly award conferred not only on artists but also on art critics, Béla Horváth’s Art Foundation in Hungary has been for years instrumental in co-financing the presentation of national positions abroad, notably at the Venice Biennale and the Documenta in Kassel. Likewise, the Stella Art Foundation in Moscow (2003) has become better known for its art management, such as co-ordinating Vadim Zakharov’s presentation in the Russian Pavilion in Venice in 2013, than the otherwise blue-chip collection of international contemporary art that it showed publicly first in 2009.

Foreigners living or doing business in the region also take part, sometimes in a pioneering way, in these schemes. Gaudenz B. Ruf, Swiss diplomat to Sofia, established the first international-type contemporary art award in Bulgaria as early as 1995, and the exhibitions and projects related to the yearly award have remained a barometer on the young art scene of the country ever since.

Companies based in Austria – such as Erste Bank, Henkel, Strabag and baumax – are spreading their business to this region, and for marketing and communication purposes often step up sponsoring art prizes and building a collection. Although company interests are obvious in these cases, discounting these projects just because they are funded by the business sphere might be too hasty. We’d better note realistically that without these awards, scholarships, research and documentation projects, publications and conferences, exhibitions and the collections amassed, the canonisation of East European art would be proceeding at a much slower pace. Also, these foreign models spur private and corporate engagement within the region, such as the company collections of Raiffeisen Bank (Hungary), Unicredit Bank (Romania), Gazprom (Russia) and, probably the best in its own right as a representative coverage of the neo-avant-garde and contemporary art of a given country from the region, that of the First Slovak Investment Company, curated by art historian Zuzana Bartosova, ex-Director of the Slovak National Gallery.

Probably the most controversial figure, Ukrainian businessman and ex-politician Viktor Pinchuk is active with his foundation in all of these terrains. The Art Centre he finances in downtown Kiev builds a collection, shows temporary exhibitions (both comprising well-marketed international stars as much as local artists), gives prizes of exceptionally high monetary value, supports Ukrainian curators in positioning the contemporary art of this young nation abroad, and does all this by using professional management and communication practice. Whilst critics from East and West alike mostly disparage these projects as mere showing-off, this overly critical stance overlooks that in this politically tormented country there being no proper museum of contemporary art and no government support for experimental creation at all, Pinchuk’s institution literally replaces all these missing public institutions and schemes.

The two prerequisites of this situation are that contemporary art receives no political backing for state representation in this country and at the same time the Ukraine is big and powerful enough to bring forward a few well-to-do people whose wealth is sufficient for funding a private museum with a full-fledged international programme. In other countries of Eastern Europe, government support for museums and other institutions of contemporary art being stronger than that, there is no such need for completely, fully replacing by private means the missing institutional network nor is there private wealth accumulated and concentrated in single hands on a level that affords funding a private museum on a global level. Elsewhere in Eastern Europe, private contemporary museum or collection/patronage schemes from Russia may be seen as similar in their global aspirations and financial backing – such as the Kandinsky Prize or the Ekaterina Art Foundation or the Art4.ru museum by Igor Markin , each in Moscow – yet we have seen in the previous lecture that the Russian scene is fundamentally different in also the state ambitiously backing public museums of contemporary art.

A range of further private initiatives could be looked at that all aim to complement, rival or replace existing / missing / malfunctioning museums of contemporary art and other public schemes of canonising the art of the recent past and present. Some areas have been researched quite thoroughly, such as by the team managed by the Vienna-based Knoll Gallery, having put together the web-site East European Collectors (EEC), with case studies on private collecting in several East European countries. Examinations reveal that the motivation for private engagement in contemporary art is rather similar in Eastern Europe to that in other parts of the world or that identified historically earlier in the 19-20th centuries. After all, collecting art is an historic phenomenon, with characteristic drives of psychological and aesthetic nature there being little specifically East European about its current resurge in our region. Yet the role these private initiatives assume gains significance due to the weakness of public museums in many of the countries looked at. In spite of the numerous biases, populist shortcomings and often too aggressive marketing strategies that seem inherent of these institutionalised private collections and patronage schemes, they help articulate positions of contemporary art that otherwise no or very limited room for expression in the public domain.

Abridged version of a double presentation in the workshop educating – curating – management at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna, 11-13 April 2014.

POSTED BY

Gábor Ébli

Gábor Ébli, born in Budapest in 1970, PhD, works as Associate Professor at the Institute for Theoretical Studies at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design, Budapest, serving as Head of the MA prog...

elmeleti.mome.hu/oktato/52-ebli-gabor-cv

Comments are closed here.