June 15, 2023

By Călin Boto

Cinema Out of Nothing: The Visual Arts Foundation

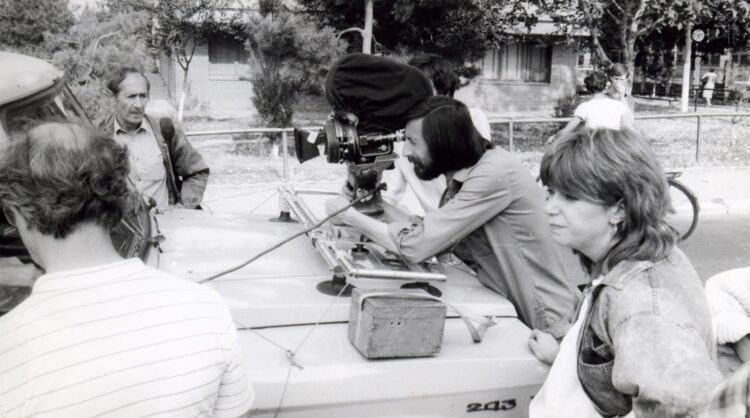

Vivi Drăgan Vasile and Velvet Moraru at the filming for “Who is right?” (dir. Alexandru Tatos, 1989)

Although I cannot precisely quote it, there is a comment by Radu Jude I’m reminded of and, looking back, the unwillingness of our film industry to make films out of nothing during the 1990s seems surprising, mainly when the big studios were barely producing from the little money they were given at will. He wasn’t referring to a particular kind of cinema, but to ways of thinking and making: fast, on the spot, somewhat similar to journalism (or rap music, as the excellent Belarusian filmmaker Nikita Lavretski remarked), without the artistic-industrial complex of making an immutable masterpiece. From the rise until the fall of the communist regime in Romania, cinema was traditionally associated with institutional networks, from studios, television, and universities to amateur film clubs; therefore bureaucratized, even if no institution resembled another. There are exceptions, of course, many more than one would think, and not all of them are as exceptional as the visual artists Ion Grigorescu and Wanda Mihuleac: some have filmed just for the sake of impressing time. The inaccessibility of cameras and cinematic film was largely obscured and exaggerated in the immediate post-communist period, so that now pre-revolution archive films surfaced; and, in theory, they are inexplicable.

Răzvan Anton: Archival Study (Portraits)

Anyway, the regime shift became a well-known trope in the history of Romanian cinema, as this is how the new order begins – Studio Sahia, as well as Studio Animafilm, goes into economic decline, being too unsustainable for the free trade market. The full-length film production is rearranged “based on the Polish model”, namely with directors, most of them prestigious seventies directors (Dan Pița, Mircea Daneliuc, Sergiu Nicolaescu, etc.), all still active in decision-making positions. So as annual budgets shrink and the economy stagnates, the decision will become easier for them – their own films come before all others. Knowing this, Jude is surprised at the lack of a rebellious, DIY alternatives from people who simply wanted to make movies, not some Free Cinematic Masterpiece (which wasn’t even meant to happen in the 90s).

Paradoxically, an exception was made by a filmmaker perfectly integrated into the official industry, cinematographer Vivi Drăgan Vasile (Moromeții, 1987, directed by Stere Gulea; The Secret of the Gun… Secrets, d. Alexandru Tatos, 1988), at the time a new professor at the Academy of Theatre and Film, where he would teach for only one generation. At the same time, Drăgan got involved in protests, first in the filmmakers’ association, then in The Golaniad; on this occasion, he also made a short documentary film of the demonstrations, along with Sorin Ilieșiu and Vlad Păunescu. Te iubesc, Libertate! (“I Love You, Freedom!”) should have been in competition at the 1990 Costinești Film Festival (at the historic edition where no Grand Prize, no Directing Prize and no Screenplay Prize were awarded), but shortly before it was denied the screen, it was finally screened through an old-fashioned deal with Dan Pița, before the feature film The White Lace Dress (1989). Even so, the film received the Audience Award, and Lucian Pintilie motivated the filmmakers to continue the documentation with a feature film that would eventually be produced by Filmex, one of the first private production companies – Piața Universității 1991, known as the film of The Mineriads.

Although he denies any involvement, I continue to believe that the creation of the Visual Arts Foundation was Drăgan’s gesture of desperate optimism: Piața Universității 1991, a bravado against the official image the University Square had on the small screen on TVR; it was possible due to the video artists of the moment, all those people, some journalists, other mere bystanders, who since the Revolution felt that time should belong to them: therefore, they turned on the cameras. Among them were the people from Video-GDS, the documentary film studio of the Group for Social Dialogue, whose coordinator was precisely Drăgan. But, he says[1], the GDS studio’s subsequent ambition to become profitable led him to leave in 1991. Instead, he was left with the idea of counter-imagination, and a year later he started his utopian project: the Visual Arts Foundation, a small video studio with equipment and premises provided by the Soroș Foundation. At last, it was possible to film freely. As was the intention throughout the 1990s, FaV was open to anything, and word spread around quickly, if only because video equipment cost a lot at the time, and Drăgan and Velvet Moraru, the producer who held it all together, didn’t ask for money for non-commercial projects. Thus, students of all kinds, filmmakers without a studio, visual artists interested in video (Brătescu, Călin Dan, Marilena Preda Sânc), but also alternative musicians (Vali Sterian, Alexandru Andrieș, Sarmale Reci) get involved. All of them are convinced that it was at least worth a try, despite the obvious: distribution happened from time to time, often through exhibitions, festivals, and ephemeral television, without any sustained interest from the official infrastructure, either public or private. Vivi Drăgan’s desperate optimism may well have been enough.

VAF showed part of its exhibition archive during the recent edition of One World Romania: video art, experimental documentaries, videos, games with special effects, etc. From time to time, someone would mention the family atmosphere of the screenings, maintained by Alecu Solomon, the de facto organizer of the retrospective: the filmmakers smiled, had much to say, they were embarrassed by the films they had just seen, and thanked Drăgan like he was a patriarch. Without a doubt, the Foundation preserves small films, many of them worth more as documentaries than artistic videos; a few exceptions are already well-known (Alecu Solomon’s and Radu Igazság’s art documentaries; in contrast, I would say that Geta Brătescu’s and Marilena Preda Sânc’s experiments have become empty with time); some have been quite surprising – Valentin Suciu’s Curtea interioară (“Courtyard”), a one-hit wonder filmmaker, 1996. Finally, some others, the most thrilling, lived their moment to the very end, with dazzling freedom, unimaginable before or after, without any claim to posterity, preserving the traces of speed, the fantasy of the moment, and the journalistic interest in the present instead.

“Penal Code was voted” 1992

Vivi Drăgan Vasile’s S-a votat codul penal (“Penal Code was voted”) has a bit of everything; and more: it is a stark art film and a miserable documentary about transition, an indifferent B and an angry manifesto made on the barricades, a poor video and some found footage of crying about the passions of communism. Made for the album of the same name by the folk musician Valeriu Sterian, then a spokesman for the anti-FSN resistance, as a compilation of ten clips, the film makes no abstraction from the popular imagery of the 1990s. That’s also because Sterian’s music was meant to be provocative, somewhere between mockery and accountability (“Jumătate și un pic / A vrut Escu bolșevic / Escu-ar vrea și banul / Și secera și ciocanul / Escu a întinat / Escu a emanat / Nu vă fie frică / Orice Escu pică”)[2]. As a whole, Drăgan has done his job brilliantly: a homeless man begging outside the Fashion store, cold penitentiary pans, mystical forests, long-haired saints, saint-like long-haired men, bloody special effects, explosions and historical protests, in short, targeted images that we often call naive in the face of their clichéd destiny, but perfectly self-aware at the moment. Giving them back their power, the DIY frenzy, is more difficult than giving them back their meaning, as we have domesticated them. Be that as it may, no amount of time will ever pull a Don Quijote on Drăgan – S-a votat codul penal was something of an impossible-to-perfect project: too much, too sudden and, indeed, too nineties-like, from a period when there was still hope for art from audiences, tall, short and neither, completely alien to the need for the cultural hyper specificity and differentiation that were to come.

Though spectacular as a souvenir, Vali Hotea’s Maya (1995) has none of the nonchalance of other VAF productions. Of course, Gregorian Bivolaru is a spectacle in his own right: seeing him up close, babbling robotically, subdued, downright placid as his eyes dart about, is thrilling and simple, but this is not a matter of Hotea’s direction, but rather one of Bivolaru’s horrification in time. Hotea’s mise-en-scène, on the other hand, is meant to be utilitarian, informative, subtly naughty and sometimes simply impressive, fascinating through the choreography of the masses, of those thousands and thousands of MISA (Movement for Spiritual Integration into the Absolute) members. If nothing of a confrontation, then Bivoleanu’s delirium would have deserved a cinematic delirium to match, at least comparable to the movement’s propaganda films inserted as found footage, hagiographies about himself, combining personal photographs with Christian, Buddhist and space iconography, interviews, Tatar documentary footage, family photos, something that looks like a Disney animation, in short, all under several voices and mystical music. You can’t keep a straight face in front of that. Behind a certain blatant formal buzz of hand-held frames and observational imagery unnoticed by bodies with their minds elsewhere, Hotea seems to have become stuck in what little space of movement he could territorialize.

“Maya” 1995

Two students, Neil Coltofeanu and Csongor Gáspár, would later pour their delirium in the diptych Primăvara (“The Spring”) (1997), based on Caragiale’s two nature poems, one optimistic and the other pessimistic. Specifically, the rain differs between the two visions of spring, which either revives the whole of nature or makes it miserable. The already simple idea was to be simplified even further by Coltofeanu and Gáspár, who animated artificial desktop landscapes with special effects featuring their own light. From the very beginning, cinema has sanctified technology, as has modern culture as a whole. Still accelerating, many of his grand attempts have lagged behind, but the big difference between the new-age CGI and this little student film is that not only did the latter make no lofty claims – and one who asks for nothing can’t be asked for anything – but that, scouring the low end of digital effects, the two found a media landscape that was to become very familiar in its naive form throughout the 2010s, then posthumous in the 2020s, as a playground: the abundance of vulgar and voyeuristic beauty, as found in photoshopped pins with roses, coffee, white doves, hearts, etc. These kinds of pictures are not only unreal but also at odds with reality, born of a desperate need for the unproblematic. It’s just that Primăvara is of a different age: you’d expect young people to find greatness in technology, yet there is something liberating about seeing a sun drawn in Paint and placed over a crooked rainbow.

Coltofeanu is also the director of Curtea interioară (“Courtyard”) (1997), the most well-rounded film VAF seems to have produced in the 1990s, one of only two that Valentin Suciu directed as a publicist. For Vasile Conta 3-5, in the shadow of the Hong Kong block, the student at that time found an unlikely bunch of neighbors sharing the darkness of that self-contained world. A ninety-year-old woman baptized in the belle époque, and therefore an imposter for almost half a century, remembers how, around 1914, she used to play war in the courtyard with the little children of the Iorga family. With this in mind, Suciu, or rather Coltofeanu (who often sweeps into the void until nothing can be seen, but beyond nothing, above, below, to the left and to the right another apartment borders), obscures the space of the block to the point of abstraction, making of it a seemingly endless, yet rather suffocating geography of sorts: the neighbors’ music blends into an incomprehensible mix through the crumbling walls, everyone knows about everyone and they’re all boxed in the same square meters. As a nod to the war game, the realities outside are essentialized on a small scale, an aspect for which Suciu retains a particular sensitivity: for example, he is told in certain words about the drunkard of the neighborhood – he keeps the harsh words to himself, but shows him upright, troubled, with tired gestures, in any way dignified. This is a film about coexistence as existence and existence as injustice, one that avoided the pornographic pleasure of gaudiness (often found in the fiery eastern cinema in the 90s), but also, in anticipation, of the farcical theisms of the social documentary that was to come later.

“Courtyard” 1997

Also, around this time, in ’97, the VAF youth countdown begins. Since the digital age had already begun, video technology was starting to spread in Romania, so the Foundation began to slowly blend in with other production houses. Drăgan continues, together with Dana Bunescu, to hold the remnants together, but the utopian moment is over; and thankfully, archived.

[1] Not coincidentally, I had the opportunity to moderate the almost two-hour retrospective discussion organized by One World Romania in April, attended by Vivi Drăgan, Marius Șopterean, Dana Bunescu, Radu Muntean, Valentin Suciu, Alecu Solomon, Marilena Preda Sânc, Velvet Moraru, etc. Much of the information I take for granted comes from here.

[2] Approximate translation: “Half and a bit / Wanted Escu Bolshevik / Escu would like the money / And the sickle and the hammer / Escu tarnished / Escu emanated / Don’t be afraid / Any Escu falls”.

Translated by Liliana Popescu

POSTED BY

Călin Boto

Călin Boto is the editor-in-chief of the cinema magazine Film Menu and the coordinator of its weekly film club. As a freelancer, he collaborates with several publications and film festivals, includin...