“Convulsion LTD. Drops on a Hot Plate” opened during the winter of 2025, organized by the Amiria Intensive initiative, a Triumf Amiria. Museum of Queer Culture program. The show was curated by the duo KILOBASE BUCHAREST in the somewhat reclusive space of The Institute, at Combinatul Fondului Plastic, with the allure of an imaginative laboratory, where different exhibition formats merge together: constructed spaces within spaces, wireframes of participatory installations, white-cube meets the black-box and mid-century drawing-rooms resonate with an oversized neon telegram. Worlds collide through the works of Apparatus 22, Maria Balea, Lucian Barbu, Alex Bodea, Ștefan Botez, Alex Horghidan, Gavril Pop, and Sofia Zadar, in installation works, video and abstract formats of new languages and political ideals. Its urgency, as implied by the title, overlaps with the constant rate of doom-scrolling in our socio-political context, so that the words ‘convulsion’ and ‘hot plate’ seem to describe what has effectively become a permanent state of nerve-prickling ennui, amid harrowing worldwide news. And yet KILOBASE is decidedly steering towards a sense of restlessness and thought-provoking questions in imagining possible presents, rather than deploring our emerging one.

With higher stakes than just one timeline, the show takes place almost ten years after the first instalment of the “Convulsion Ltd.” series, the 2016 solo show of the 1980s Romanian artist Christian Paraschiv and his previously considered taboo works on the human body. Departing from the rediscovery of his works by a new generation of curators and fellow artists, the curatorial team revisited the censored past, its joys and denials, its pleasures and misery in today’s political landscape. New artistic voices were brought forward, through the door left open by the second show “Convulsion Ltd.: further thoughts from new associates” that ran in parallel with Christian Paraschiv’s solo in 2016.

The present and third iteration moves towards a more analytical stance: a critique of the museum and its rituals, with the oversight of Triumf Amiria, especially in the impoverished and mainly conservative institutional art context of Romania. Curation and art mediation are part of the exhibition from the very moment that the visitor sets foot in the space, especially through the collective mindset works of Apparatus 22, continuously asking, deconstructing, writing and over-writing as a meta-voice to the show. Unfortunately, this does not make the exhibition any easier to grasp. The whole set-up and conceptual experience feel heterotopic to say the least: Alex Horghidan’s Pretty (bad) Tattoo installation of an actual tattoo parlor, Lucian Barbu’s graphic testimonial of labor laws and worker protection, and Gavril Pop’s abstract textile installation make for a difficult read thus presented all at once, on such apparently different topics. It makes one wish that each of the sub-themes could expand further in a larger conversation, perhaps even in a full-blown, more permanent alter-institutional program.

Rhythms and stories of the body

When the show does take lengthier visual pauses, it does so in all the right places, either with Alex Bodea’s arresting cut-out stories of sexuality and power, tenderness and pain, or Maria Balea’s disembodied experience as the ghost-in-the-machine with Corrupted Data in the Cloud, and A Change of Perspective series of drawings and paintings. With enough distance, and having the time to explore each work in part, the kaleidoscope that forms is an argument for intersectional particularities, something that translates in my mind to the manifesto of Glitch Feminism of Legacy Russel, but without the digital disembodiment that is so central to its non-binary cause: for my body then, the subversion came via digital remix, searching for those sites of experimentation where I could be my true self, open and ready to be read by those who spoke my language. Instead, the show brings forward an overwhelming argument for the acceptance of the very physical non-binary body into new spaces that can translate, accommodate, and most importantly, not shy away from the discomfort, the pain and the pleasures of a world unhidden.

“Could the museum of the future turn into a form of social narration?” is one of the Apparatus 22 artwork-questions that stayed with me the most, alongside “What if bodybuilding strategies shaped a queer museum?”. It brings into focus the need for a more mediated contemporary art dialogue, something that has been a staple piece practice for the artistic collective of Apparatus 22 from its beginnings, at times through the many iterations of their Positive Tension (in the air) series. Perhaps, on the high-rise of the radical right and the instrumentalization of the LGBTQ+ rights on the political arena, this is now more urgent than ever. It also echoes into the importance of taking note of our own bodies within the body of the institutional Leviathan, as either art workers, or visitors, with nuanced degrees of separation, to the point of border, or membrane, dissolution.

Nowhere is this more visible than in the fresco-like drawing installations of Alex Bodea, whose works are deliciously subverting more common expectations of art. Alex Bodea usually works off written notes of observation and this shows in the visual storytelling that she is unravelling. Cruising (boys checking out boys, girls checking out girls) is a tender observation of the laws of attraction, under its fluctuating and queer forms. Within the exhibition space, her classical-taught style seems to be re-writing pages out of art history books, had they not been read through patriarchal lenses for so long.

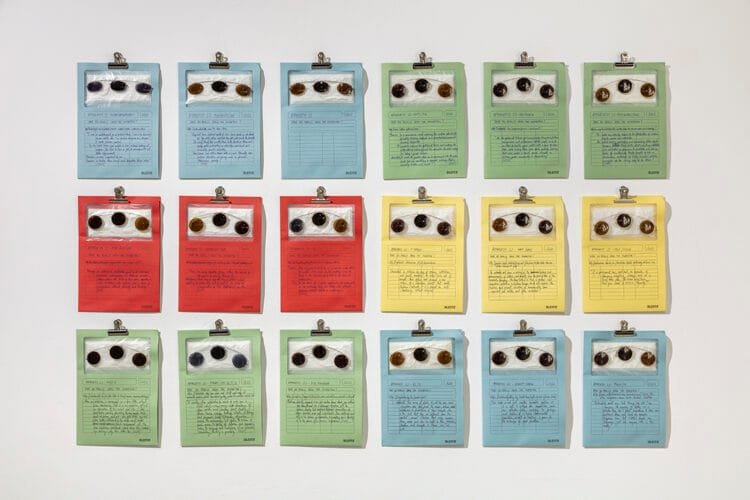

This is also voiced in the installation Have You Really Seen the Exhibition? of Apparatus 22, which contains dossiers with suspended tri-ocular spectacles, making room for a third-eye awakening and understanding of the discourse presented throughout the show. While these works openly mock a certain bureaucratic museum thinking, they also reveal a certain engaging obsessiveness with filing, recording, maintaining perception alive through notes and the second-hand experience of other exhibitions. For example, one of them poignantly reads: “If a government has, and had, an agenda of damaging everything, always, and as a long-term plan, to erase everything, then you need to archive. Urgently.”

The invisible walls and the voice therein

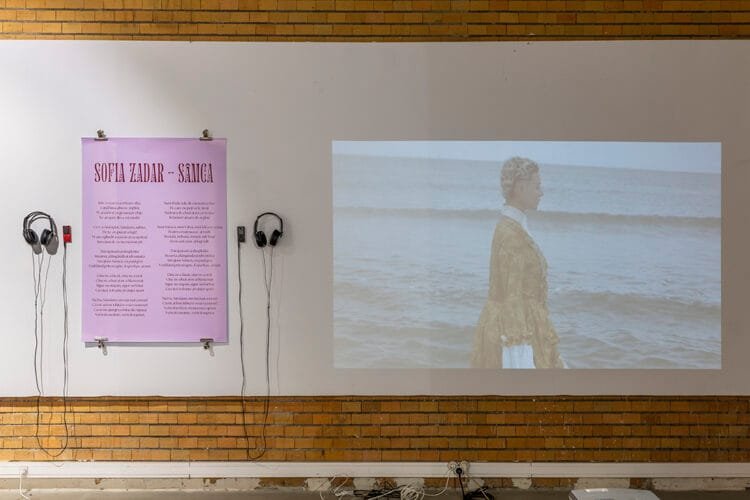

Centered through other notes either calling for the re-thinking of what freedom means for artists, or how another show contributes to the understanding of homo-eroticism in Eastern Europe, the work Have You Really Seen the Exhibition? enables the reader to grasp how a different worldview could emerge from the fringes of previously repressed identities and forms of pain, love, sex: Sofia Zadar’s songs swivel around these themes in particular, borrowing the rhythm and beat of heart-breaking pop love songs, to more visceral lyrics calling for societal change: „Sunt fricile tale de oameni ca tine/ Pe care nu poți să le simți / Sunt ura de clasă și sex ce te ține / În lanțuri amare de-arginți” [“I am the fears of people like you/ Those you cannot feel / I am the hatred of class and of sex that keeps you / In bitter chains of silver coins”].

In their video and object installation The Monster’s Tools, the rejected and the outcasts take their agency back. The video plays in an iron cage-house, as a built-in oratorium, from where Sofia Zadar’s alter ego Toiboy speaks and sings. It is not just Audre Lord’s wordplay that invites us to dismantle the old walls, but also the artist’s plea to do so without renouncing the claws. What others consider monstrous is just a way to marginalize, to mythicize and to justify diminishing a much more diverse and slithering reality, to the point of invisibility, which emerges as a large underlying theme of the whole exhibition.

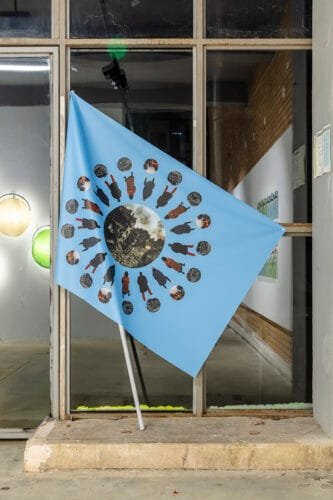

Due to recent personal obsessions, and readings, I keep going back and forth between thinkers Axel Honneth and Jacques Rancière and the way that they define matters of social visibility or the lack thereof. According to them, the latter constitute critical lenses through which exclusion and oppression can become recognizable. What do we choose to see? What do we choose to ignore? And how do these add up to a world that does not act and think in binary terms? Some of the artworks in the show are decidedly at that threshold, between distance and dissonance, where reality is abstracted at the edge of what can be politically, socially, humanly understandable and endurable. The three flags hoisted against the window in the exhibition space, under the title Everything at a distance becomes abstraction (also Apparatus 22) show several silhouettes looking towards scenes of terrible destruction as a small crowd of Caspar David Friedrich Wanderer above the Sea of Fog-figures, set in various patterns and geometries. The passivity of the observers and the minutiae of the sites of violence both nullify the nationalist symbolism of the flag and bring forward an odd relationship between witnessing and being embedded in the horrors of the contemporary world.

The choice to remain invisible can also be a resistance mechanism, as Honneth underlines, against oppressive orders of surveillance and incessant categorization. In that sense, Gavril Pop’s Plans for an announcement appear mounted as official banners to a mysterious procession with an otherwise intentional twist for the anonymizing discourse. At times organic, at times reminiscent of the military symbolism induced by the olive drab and blunt lines and arches, the installation pendulates between future protests with insignia for a resistance yet-to-emerge. In the same sense I connect Visions, a series of drawings on paper by the same artist, of different stylized monumental temple-like contours with a continuance of these future-preserved intuitions unveiling invisible allegiances and forces within abstraction.

Letters from out there, reading from in here

Thus alternating between the political, the mystical, the personal, this iteration of Convulsion Ltd. brings forth a constellation of behaviors and flowing states of mind. They are viscerally connected to the body, like a spine that cannot help but coordinate signals to muscles, blood flow, breathing ribcages. It feels multi-purpose, but it also feels necessary. The outside context was very important to how this show could be metabolized. The exhibition opened between the two rounds of presidential elections, one more ridiculous than the other, at the end of year-long local, parliamentary and European elections and useless referendums, full of false patriotism, hours long empty debates and promises appealing to an electoral body or another, more effectively polarizing friends, family, strangers.

The invisible has been made visible to be tokenized or transformed into an object of political competition and social hatred. Beyond the discursive analysis of the works, in the compact vision of Triumf Amiria, the importance of world-dreaming breaks through, especially in the suffocating and underfunded art scene in Romania. Perhaps one day we will be able to talk more about the queer museum replacing the megalomaniac absent ones, where the public and the artists may enjoy uncertainty in the vein of fluidity, not in the making of survival culture kits; politics under the form of path-forming rather than the ritualistic sacrifices of exclusion, and superficial, ready-made shows to fit it all as I have seen all year round in Bucharest so far. Exhibitions such as this one, with momentum and labyrinthic strategies for further attempts are necessary experimental exercises, able to center queer artist voices at the intersection of our day-to-day lives, and thoughtful dreams and monsters free.

The exhibition “Convulsion LTD. Drops on a Hot Plate,” curated by KILOBASE BUCHAREST, artists: Apparatus 22, Maria Balea, Lucian Barbu, Alex Bodea, Ștefan Botez, Alex Horghidan, Gavril Pop, Sofia Zadar, took place at The Institute, Bucharest, between January 18 and February 23, 2025.

POSTED BY

Cristina Stoenescu

Cristina Stoenescu (b. 1989, Bucharest) started from Political Sciences with a paper on the Union of Visual Artists. She continued to study art in two consecutive master programmes in Bucharest and Ma...

Comments are closed here.