Among this year’s notable reconfigurations is Estonia’s presence in the Giardini, in the Rietveld Pavilion, taking the place of the Netherlands. The building houses Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance, an exhibition that has orchids and their journeys at its center. It was curated by Corina Apostol, one of the Romanian names that one has been hearing more and more often on the international scene.

Corina Apostol is a curator and art historian who has been the curator of Tallinn Art Hall since 2019. Born in Constanța, she received her bachelor’s at Duke University and continued her studies at Rutgers University, through which she would become a researcher at the Zimmerli Museum, where she would develop her research on Russian art, for which she would be nominated for the 2016 Kandinsky Prize. Among her other activities, I would mention her involvement in the Creative Time organization (for which she received an Andrew W. Mellon Grant) and being the cofounder of ArtLeaks.

You trained as an art historian in an American academic context. You were telling me another time that even though the thing we historically had in common with America, the Cold War, was for them, at the time, an almost unacknowledged part of history, you came to specialize in Russian art. This is a space whose ideas from the last two centuries have also been at the forefront of debates within the contemporary art establishment. Paradoxically given present circumstances, the space of Russian art used to be a visionary, anticipatory one.

When I was 19, I left Romania to be educated in the United States and spent most of my adult life there looking from the outside so to speak at the non-conformist and dissident artistic practices in the late Soviet period (the 1980s). I think this separation from my home context has given me a more critical lens to look at my own culture and to understand it in the framework of the larger geopolitical processes of the Soviet Union as it disintegrated and then the consolidation of the new European Union. Because of the distortions and manipulations that happened in presenting recent history in textbooks in Romania (for example there was no discussion of the Holocaust or the nationalist dictatorship in Romania when I went to high school), I had to re-educate myself and also my colleagues and professors about what is this legacy and why it matters beyond our region, as this is a shared East-West history.

After studying representations of trauma in art with prof. Kristine Stiles at Duke University, I discovered my passion for art history and visual studies. I focused on performance art and other interdisciplinary art practices during my studies, with a particular focus on Eastern Europe and Russia. At the time I was very interested in what Stiles coined as “cultures of trauma”, to theorize visual depictions of this global phenomenon in art, film, literature and society. During art history courses, I looked at different case studies, the Nuclear Age, the Holocaust, the dictatorships in Latin America and Eastern Europe, focusing on artists’ impulse to narrate and describe suffering, pain and dissociation caused by traumatic events, and their struggle to materialize through art and bear witness to the voices of survivors.

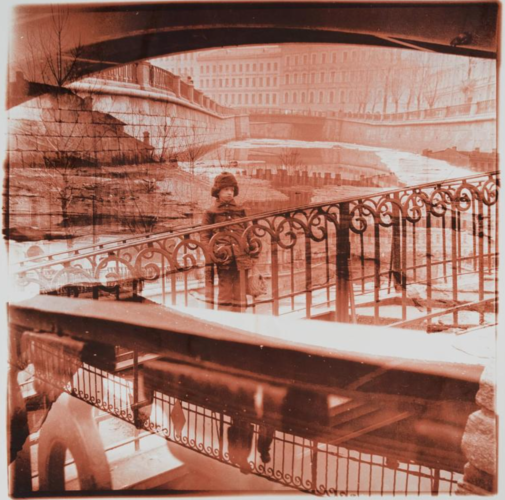

I went on to obtain my PhD at Rutgers University, where I worked on the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union. It was an amazing opportunity to research and curate this collection (which includes over 50,000 pieces, as well as archives), which was amassed largely during the Cold War by Dodge himself and other curators and then smuggled to the US from Russia and the former Soviet Republics. It is incredible that not a lot is known about this collection outside of the Zimmerli museum and the NJ-NY area. It represents a massive part of the cultural legacy of our region. Thanks to a scholarship from my university, I was able to travel to St. Petersburg over the course of four years and to take Russian language courses, as well as interview some of the artists in the collection. As the capital of the Russian Empire for two centuries, St. Petersburg occupies a unique place in the history of Russia and Europe. During the first half of the 20th century, this canal-linked city – popularly known as the “Venice of the North”— experienced three revolutions, civil war, and a devastating 900-day siege during World War II. Despite this turmoil, St. Petersburg preserved both the atmosphere of its grand 18th-century beginnings and the legacy of its early 20th-century utopian avant-garde movements. Like their avant-garde predecessors from the 1920s and 1930s, these nonconformist artists worked and exhibited together, seeking to reorganize their world, transform communism, and rewrite history yet one more time.

As with most revolutionary periods, the legacy has been a mixture of failure and success. While the so-called “free market” emerged, it has proven to be a long, chaotic transition to capitalism, with an extremely high cost of living and often unreliable supplies of necessities. Ironically, artists who enjoyed creative freedom during “perestroika” have been forced to pursue more steady careers, sacrificing time devoted to their art. In addition, intolerance has resurfaced, with recently enacted anti-gay legislation and now the war of aggression against Ukraine when local resistance is atomized and virtually impossible due to draconian laws that forbid dissent or any mention of the war as such.

The first exhibition you curated that was fundamental for your career was Leningrad’s Perestroika. What directions did you follow back then?

Young people were restless in the late 1980s and turned to art to express themselves in a city repeatedly at the forefront of change, embracing a DIY attitude in all their endeavors. They experimented with photography and the newly available medium of video; their music declared personal and global anxieties. In my exhibition Leningrad’s Perestroika: Crosscurrents in Photography, Video, and Music, at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University (2013) I examined – through the eyes of these artists – the final years leading to the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, as well as its immediate aftermath. From 1985 to 1991, Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, instituted a series of reforms known as “perestroika” (restructuring) and “glasnost” (openness), which were intended to upgrade the existing Communist system rather than overthrow it. These efforts continued, following the dissolution, through 1993. During this period, many artists had “day jobs,” allowing them to make a living and pursue their creative visions in a relatively inexpensive and stable economy.

Drawn from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, my exhibition presented the largely overlooked, provocative counter cultural milieu that existed in Leningrad. I exhibited more than 60 photographs and videos, the exhibition presents – for the first time – photographers, musicians, and video artists as active members of groups, rather than individual producers, to underscore their collective goals. Most of the works, which were created between 1985 and 1993, had not been seen by the public in the United States. In addition, I translated from Russian interviews with – and critical writings by – the artists present firsthand accounts of participation in these unofficial cultural networks.

In the Soviet Union, photography was not officially considered as art; it essentially served as a documentary tool for state propaganda. This attitude allowed amateur photography to flourish unrestricted by professional conventions. The series Nomenclature of Signs (1986-1991) by Alexey Titarenko is an example of rarely seen conceptual photography from this era. He painted a picture of the late Soviet Union through the lens of Leningrad, where people live in a world of unrealized hopes and time seems to stand still. Dmitry Vilensky developed an artistic method that he coined “photo-archeology” or “photographic excavations into the past,” which overlap imagery from different times and places. He created scenes that are familiar, yet distorted and dreamlike.

I also looked at how music also flourished, though musicians faced more government oversight. Western rock music was officially banned. Citizens smuggled cassettes or covertly tuned in to Voice of America and BBC broadcasts to keep up with the trends. Leningrad became the center of a music revolution, with bands such as Alisa, Avia, DDT, and KINO who wrote anthems for their generation. They used music to express their excitement – and anxiety – about facing adulthood, as well as drastically changing political and economic climates, at home and abroad.

Photographer Andrei Usov chronicled this underground rock revolution, generating an extensive archive of images of Soviet musicians and their audiences. His iconic 1985 photo-posters capture the legendary rock band Akvarium (Aquarium). The band produced what some consider the epitome of “perestroika”-era Leningrad rock: Partisans of the Full Moon (1987), referring to the fact that many of these bands recorded their songs at night, as recording outside official venues was against the law.

Photography, film, and video became more prominent in documenting performance artists, as well as outlets for actors and writers. In the late 1970s, a group of Leningrad artists began to stage provocations: bizarre events that took place in public spaces, to the surprise of passersby. This practice led to the artistic movement termed Necrorealism, which paradoxically combines references to death and life. In the early 1980s, the group, spearheaded by Evgeny Yufit, began filming their provocations on 8 mm film, establishing an alternative cinema in the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, these films began to reach international audiences.

While state-owned media did not show experimental creative work, it was widely popular in the unofficial art world. Piratskoe Televidenie (Pirate Television) was produced by several artists between 1988 and 1992 in a Leningrad apartment. It ran as an alternative news source to official Soviet TV, featuring news, films, sports, and music programs narrated by a host of colorful characters. Most notably, this mock program’s anchorwoman, Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, became the Soviet Union’s first public drag queen. His popularity also reflected the growing acceptance of the gay subculture in Leningrad.

Looking now back at this show and my years long research in St. Petersburg, on the backdrop of the unfolding Russian war against Ukraine, it is clear that the legacy of the 80s spirit of experimentation and political redefinition has been but erased by the Putin regime as any current possibility of resistance from artists or activists is virtually impossible. At the same time, the Cold War era is now more present with us and it is important to remember this cultural history and try to learn something from it.

In the United States, besides your work as an art historian, you have also worked with community art, as you were part of the extensive Creative Time initiative, with two key moments made possible through your activity: Creative Times Summit Miami 2018 and Bring Down the Walls.

The Summit was first conceived in 2009 by Creative Time’s former Artistic Director, Nato Thompson. Since its inception in 2009, the Summit has functioned as a flexible, roving platform bringing together artists, activists, and other thought leaders engaging with some of the most pressing issues of our times. Having emerged alongside the definition of political art, or socially engaged art, the Summit highlighted and united artists and practitioners working beyond the traditional art market, many of whom were intervening in areas of civic life, politics, and media. I think the Summit is a fantastic platform with great potential for fostering meaningful connections amongst a growing global community, while also highlighting locally-driven programming. I was involved in the curation of the last three editions in Toronto, Miami, and New York. It was great for me to operate in those contexts and learn more about the communities working for social change in North America. It is not only about intellectual ruminations, but our attendees over the years have been exposed to some fantastic workshops, performances, roundtables, and films which have provided concrete strategies for social change in the local and global context. Creative Time keeps an archive of all these activities on its website which is freely accessible.

When I joined CT in 2016, I was actually commissioned to write a book on the occasion of the 10-year anniversary of the Summit. My book Making Another World Possible analyzes many case examples of socially engaged art projects which have direct consequences on politics or whose effects are visible in society. We wanted to bring together and without any hierarchy artists who are perhaps more well known to the public (Pussy Riot, Chto Delat, Carlos Motta, Zach Blas, Nastio Mosquito, Regina Jose Galindo, Xu Bing), with actors that are not so well-known internationally, such as Roma artist Marika Schmiedt and her magnificent protest posters, as well as many artists and citizen initiatives from Puerto Rico, Guatemala, Indonesia, Thailand, South Africa, Ukraine, and the Middle East. Russian artists from the group Chto Delat?, who created the cover for the book and a timeline of socially engaged art said about their art practice: “We understand that the world is changing and we see that there is a certain fight. In my optimism, I see that the fight is not yet lost completely.”[1]

You are among the founding members of ArtLeaks, one of your few professional connections to the Romanian space, unfortunately. Please tell us about how this initiative came about, how it used to work, about the collaboration with tranzit.ro/bucuresti, and about how the platform works nowadays.

I had a first-hand experience of how art that is meant for the community ends up being just a dollar figure in the well-oiled machine of commercialization. I can say today it is almost impossible for artists to delineate themselves from this system because it is part of the world we work in. Also, artists are relying on galleries to make ends meet and larger commissions from biennales and museums to put together projects that they need institutional support to carry through. The problem for me is when socially engaged art becomes more about pleasing certain collectors and buyers, or when the message of the project becomes co-opted and misrepresented, or when artists and their collaborators are not being compensated for their work. There is a lot to untangle here, and the first step is the realization that there are a lot of problems with how the art world works, just as there are in the world we are living in today. In 2010 I co-founded an activist platform, ArtLeaks which precisely deals with these issues in the international context. The project was born out of a case of toxic leadership of an art space in Bucharest, Pavilion Unicredit. Several founding members from Eastern and Western Europe found it important to break the silence around the bad practices of the space and then we decided that it makes more sense to open up a space online where anyone could submit similar cases.

ArtLeaks has developed in the direction of joining forces with other international actors to expose not only this or that bad situation but reveal the mechanisms that perpetuate a system that we all agree is broken and abusive, and to build awareness that these mechanisms are not exclusive to the art world. I think we can build good examples and best practices by joining forces with activists who are asking similar questions about governing our everyday lives, and our societies.

In 2013 I collaborated with tranzit.ro/Bucharest to curate a series of workshops in their space that were free and open to anyone who might be interested. In these workshops, together with guests such as philosopher Vlad Morariu, artist Dmitry Vilensky, accountant Andi Gavril, curator Anca Mihuleț and lawyer Mihail Macovei we analyzed how cultural producers have organized in the past and the present to improve not only their living conditions, but also political, social, and economic processes at large. We problematized the classification of cultural activity as labor, tested the viability of “cultural producer” or “cultural worker” as a collective marker of subjectivity, and looked at culture as a field of but not limited to labor practices that affect society. One of the major themes of these meetings was the historical relationship between art, organized labor and social movements in the age of capitalist globalization, and in order to decipher these structures and the connections between them we looked at a variety of examples of local struggles, alternative models and international networks. I believe we were successful in encouraging those who participated to imagine their own alternative models, list of demands, manifestos, ways in which artistic labor can be collectivized, new institutional models.

What brought you back to Europe? How did you become the curator of the Tallinn Art Hall? How does this institution, and the contemporary art system there, work?

After working for more than 10 years in the US art institutional framework which runs like a well-oiled machine, I realized that it did not need me so much and I achieved my goals: I had my Ph.D., I curated exhibitions and conferences at prominent institutions, I completed my first book in English published by a major publishing house. When I left in 2019, the Trumpian politics in the US were becoming more and more violent towards immigrants such as myself, and maintaining a curatorial practice there was precarious and volatile. While there is a lot of expressed support for immigrants working in the arts, the reality is that we end up fending for ourselves when it comes to dealing with the legalities and costs of getting work authorization.

I was looking to return to the European context and work on projects where I felt I was truly needed and could make a significant impact. I was very impressed with the energy, passion, and professionalism in the Estonian art scene, and I felt truly welcomed to Tallinn by the team of the Tallinn Art Hall. I am grateful for the opportunity to be the first international member of the institution, and to build something exciting and meaningful together. Tallinn’s context at the intersection of geopolitical forces, its proximity to Russia, East-Central Europe, and Finland and all the cultural ebbs and flows that come with this location were also very attractive to me.

The Art Hall is publicly funded by the Ministry of Culture of Estonia and is one of the largest producers of art exhibitions in the country, showing regional and international projects. There, I have had the opportunity to create exhibitions and programs that foster connection and solidarity between local and global actors. Since I joined the team, we have consistently provided programming in three languages (Russian, English, and Estonian), we have expanded our communication towards differently-abled people and created an online platform to present our exhibitions internationally.

In the three years that I have been working at the Art Hall, I have tirelessly fundraised and lobbied to make more possibilities for both artists working in Estonia to be exhibited and receive recognition outside of the Baltics, as well as to create more collaborations between artists from Eastern-Central Europe and beyond and the regional context. I am very happy that my cultural endeavors have been deeply felt in Estonia and I have succeeded to bridge some of the distances between this context and my international colleagues.

You are also a tutor in the POST Program, at the Riga Art Academy.

I first visited POST in September 2021 at the invitation of Kristaps Ancāns, an artist, writer and educator who I have been collaborating with this past year. In Latvia, and in Eastern European art academies in general, traditional approaches to painting and sculpture continue to dominate over conceptual approaches to art and critical thinking. In response to this, Ancāns created POST, an innovative multidisciplinary master’s program within the Art Academy of Latvia. The program is committed to deepening artists’ community engagement, expanding art education in the region, and exploring ideas of art in context.

Since Spring 2022, I have been working with the POST group of tutors who are artists, poets, musicians and philosophers – including Ancāns, art historian and curator Ieva Astahovska, philosopher Artis Ostups, literary critic and musician Jānis Ozoliņš, artist and curator Kaspars Groševs, poet Kārlis Vērdiņš, artist Armands Zelčs and artist Amanda Ziemele. I am very proud to be part of this educational and artistic platform for aesthetic and intellectual exploration. Over the course of a year, POST has been fostering new artistic talent in small groups, creating a supportive environment for young creatives to understand their own history and identity and also to channel their questions into the creation of new methods of artistic practices that find their way into the public sphere in an integrated Europe and beyond.

POST’s socially and politically charged courses, informal conversations, experimental practices, and everyday experiences encourage students to think, create, feel, and laugh all at the same time. It is quite rare for MA programs to encourage these qualities at the same time, I believe this combination in the Baltics is significant to engage with the cultural, social and political context. As we are now living through the threat of war in Europe which is literally at our doorstep, we need to find ways to coexist, survive and confront the painful experiences related to the pandemic, the is vital in a cultural and political context in the Baltics where questions of autonomy, construction of knowledge, and the need to confront painful experiences related to the crisis and the looming threat of another war in Europe are ever more demanding.

You are also involved in the Pan-European project Beyond Matter, which tackles the journey of artistic heritage and the culture emerging in the digital space.

With the recent acceleration of digitization of the arts worldwide during the pandemic and ensuing crisis, this long-term project will serve as a timely resource to reflect on and analyze some of the latest artistic solutions and platforms that give access to knowledge and culture remotely in unique and affective ways. We imagine the different components of the Beyond Matter project will serve as a resource and reference for those already involved with virtual reality and digital art practices, as well as for those art world insiders who would like to learn about, pursue or support engaged immersive art projects.

Over the course of the project, we have organized a residency program, and several discussions and are now planning an exhibition and related publication. For example, I hosted artist, writer and digital curator Dennis Dizon who spent two months in Estonia looking at the intersection between the virtual condition and the ecological crisis. He created an interactive workshop and a research performance that invoked a queer approach to sharing stories and encounters between humans and nonhumans (algorithms, machines, nonhuman animals and other entities) through videos, texts and images, attempting to recover from trauma, violence and coloniality. I also invited curator and art historian Helen Kaplinsky to be in residence with us, which she spent exploring the virtual technological and mystical visions of women. For her concluding public event she created a rich program inviting speakers such as art historian Anu Mänd to highlight gender, death and animal symbolism in the late medieval Baltic region, artist Dominika Trapp, who created a performance about her coming of age as a young woman in the Hungarian countryside, discomforts with contemporary feminism and her commitment to somatic intelligence, and also organized a VR screening of Tragodia by artist Tai Shani, a play about three generations of women in the artist’s family and their nonhuman kin.

Together with artist and educator Kristaps Ancāns, I organized a series of talks approaching the virtual condition from different perspectives. We were in conversation with philosopher Boris Groys looking at how augmented reality tools can bring back monuments that were once taken down such as statues of Lenin and how we no longer relate to the forum of these monuments, from the point of view of a generation that did not directly experience the past when these objects were created and have different perspectives and therefore relationships to it. Kristaps and I also invited artist and filmmaker Shu Lea Cheang to discuss how new technologies and strategies of queering tools of the virtual condition can be used to shape performances of gender, enable gender play, and transform bodies beyond conventional sensualities, sensitivities, towards new horizons beyond power structures which we are already used to. Next, we also moderated a panel discussion with artists from POST offering practice-based and poetic perspectives of the younger generation in art on the virtual condition and its applications in present-day art in the context of the Baltics, a context where there has been a recent influx of virtual and augmented reality endeavors, bringing together technology entrepreneurs, experts, policymakers, creatives and writers from all over the world, to solve problems caused by the clash of the analogue and virtual worlds. Our latest dialogue with my colleague, artist and writer Zach Blas centered around questions related to what lies behind our desire to create AI technologies, and why we develop AIs in human form, looking at our craving to replicate ourselves and/or the idea of a creator or god. Through this conversation series, with Kristaps we wanted to bring more awareness about what happens when technologies, devices and digital tools enter our cultures, local politics, our daily lives. I believe we have brought an exciting array of speakers closer to audiences in the Baltics, as currently there is no other cultural platform offering critical insight into these questions, even though they are critical to navigating the local and international landscape.

An important moment of your activity in Tallinn is the exhibition What Makes Another World Possible?, another example of socially engaged art in your career. You also said that this exhibition contributed to your being nominated as a curator for Estonia at the Venice Biennial.

It was my dream to organize an exhibition based on my book Making Another World Possible which came out in 2019. Because of the pandemic, I could not stage the show until 2021. While the topics of the exhibition were as urgent as the issues my book highlighted, the crisis brought even more uncertainty and intensity to certain pressing issues in the world. Still, when putting together this exhibition with artists from the Baltics and others from the East-Central Europe context and beyond, I was guided by the belief that artists contribute to some of the most crucial debates of our times and that their voices are significant in shaping society and imagining how it could be different.

Both my book and the exhibition examined ten global issues through the prism of socially engaged art projects, including the militarization of society, the proliferation of surveillance, entrenched economic inequalities, rising social movements, the displacement of peoples, cosmopolitics, anti-racism struggles, creative education in crisis, queerness and political expression, and new devices enabling political action. Rather than attempting a global survey, the adaptation of this book into a physical exhibition was for me a strategy to raise fundamental questions that initiate conversation and contribute to the understanding of socially engaged art both in Estonia and abroad. The exhibition introduced audiences to which current issues speak to artists and how art is responding to the present political questions and relating to the global situation here and now.

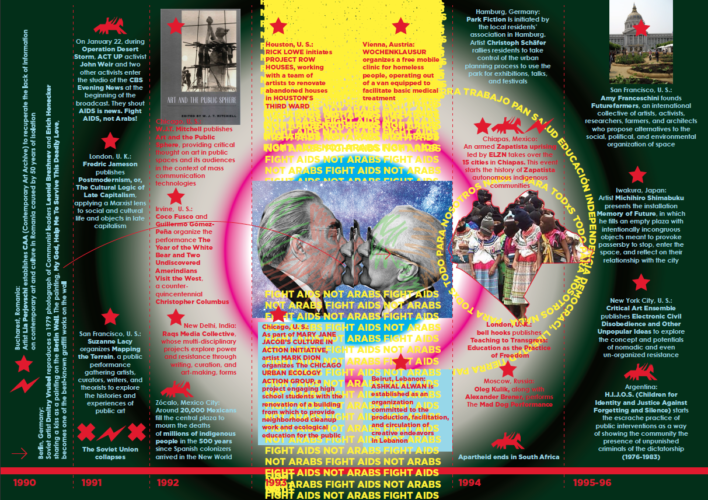

Several new commissions were featured in the exhibition, including the installation On Art, Politics and Engagement: A Timeline where I closely collaborated with the St. Petersburg-based collective Chto Delat, about whom I had previously written on in my dissertation. For the collective, timelines are artistic tools for re-staging political history: they mark a shift from the traditional understanding of the artistic or historical archives of the Cold War which merely present on historical events, to providing a space for reflection and activism around the social and political relevance of aesthetic representation of those moments and actors. The timeline, presented in the exhibition as an installation, first appeared in my book as a starting point for inquiry, from activism to aesthetics, from the historical events to happenings, and from the local to the global. Our selection for the installation at the Tallinn Art Hall included landmark events, key projects, actions, initiatives, thinkers, and artists that shaped and guided the practice of socially engaged art with a particular focus on the Baltic region. Their engagements, aspirations, and propositions to a volatile and confusing era provide much-needed inspiration for the challenges ahead.

How did you win the Estonian project contest for the Biennial? This year’s Estonian pavilion, called Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance, is at the complex intersection between environmental discourses and the various facets of colonial history, through the pretext incited by the Estonian-born botanical artist Emilie Rosalie Saal.

Beginnings always start with conversations or the desire to have a discussion, exchange ideas and explore. Two years ago, artist Kristina Norman introduced me to the biography of Estonian writer, photographer, and topographer, Andres Saal who worked and lived in Netherlands-colonized Indonesia together with Emilie over a century ago. We were immediately drawn to her story, as so little was known about her as a woman artist raised in Tartu, Estonia, educated in St. Petersburg, Russia, a resident of Jakarta and eventually a US citizen living in Los Angeles, CA. While her own work was overshadowed by her husband’s career, merely mentioned as a footnote in his biography, she gained the power to pursue art, focusing on unique tropical orchids and other rare tropical flora. Once a colonial subject in Estonia herself—then part of the Russian Empire—Emilie eventually became an elite member of white Dutch colonial society in Indonesia, at the turn of the nineteenth century. As an artist, she relied heavily on the labor of Indonesian women and other indigenous servants to fulfil her practice, travelling widely throughout the archipelago.[2]

The concept of the exhibition Orchidelirium: An Appetite for Abundance then emerged out of my discovery of the works of Emilie Saal.[3] Although her legacy was lost in Estonia, I discovered lithographic copies of her art in the United States where she emigrated later in life, including its significance in the native context of today—a provocative case study in entangled histories of self-determination, colonial experiences, neo-colonial structures, botany, science and art.

Our initial conversation with Kristina Norman turned into a long-term project during which we encountered unexpected stories and people connected to Emilie’s life, work and world travels. We invited Bita Razavi, an artist originally hailing from Iran, who spends time between Finland and countryside Estonia, known for her work that critically reflects on her identity at the intersection of several cultural contexts, to join us in the discussion and to shape together with us the project Orchidelirium.

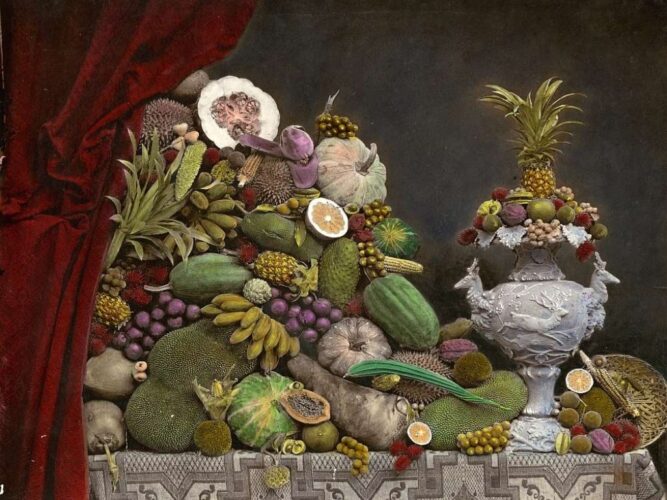

I named the exhibition Orchidelirium,[4] which refers to the “orchid madness” that gripped Europe over a century ago. The subtitle An Appetite for Abundance was inspired by a painted photograph from Java (taken by Andres Saal and overpainted by Emilie) that depicted a lush still life of fruit and vegetables stacked on top of each other in a pyramid, framed by a deep red curtain and an ornate relief cup with stags. The subtitle makes reference to the insatiable appetite for reaping “exoticized” flora from its indigenous environment to be translated into European visual cultures that feed into colonial, commercial ambitions.

Please explain to us the Pavilion’s configuration.

While constructing my curatorial strategy for this project, I noticed the striking similarities between the extraordinary circumstances of Emilie’s life and the unique development of the Estonian Pavilion for the 59th Venice Biennale 2022. The Mondriaan Foundation’s invitation to take over the Rietveld Pavilion presented our team of artists, producers, and commissioners with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to take the stage. From past relegations of Estonia’s art pavilion representation in other locations within the City of Venice, we are now in the Giardini, at the center of power and visibility in a historic building designed by Gerrit Rietveld, one of the most renowned architects in Dutch history.

Similar to the biography of Emilie Saal herself, the exhibition that the visitor encounters in the Giardini offers a protean set of questions, curiosities, differences of opinions and ideologies that encounter each other under the same modernist roof of the pavilion offered to us by the Dutch. Kristina Norman addresses Estonia’s past, in her film trilogy (Rip-off, Thirst and Shelter) referring to experiences of serfdom within the Baltic-German feudal system through a botanical perspective, and stretching to the present-day ongoing exploitation of orchids grown in vast amounts in nurseries in the Netherlands and bogs from which peat is extracted in Estonia, peat that then serves as a substrate for the flowers. Eko Supriyanto’s film Anggrek (Orchid) is in dialogue with and interrupts the trilogy at specific points. Shot on location in Central Java, in a rock quarry where mining exploitation still happens, the film contrasts the “fragility and struggle of nature” against “anthropogenic exploitation”[5] featuring strong, resilient gestures by Supriyanto and dancer Putri Novalita. Bita Razavi’s strategy for engaging with the subject matter is to make material and formal references to both Indonesian and Estonian cultures and traditions. Her work has taken the form of spatial installations inside the pavilion (titled The Allegory of the Cave, Elevation, Kratt), where she critically addresses who and why should speak about privilege and in what context and engages audiences to reflect on their own, as this hierarchies relate to the power dynamics between colonizers and colonized.

My research, assembled with the support of advisor Sadiah Boonstra, and visualized in collaboration with artist Kristaps Ancāns who helped design a timeline for it, is also presented within the exhibition, connecting different geographies and temporalities through the metaphor of flowers, or more specifically, orchids. All these perspectives and different strategies have played out in the development of Orchidelirium, where the consensus has been as important to the process as the dissensus between the artistic team. We have collaborated on weaving together different sensibilities, experiences and approaches of a diverse team of peoples, where theory and practice have been sometimes at odds and at times intertwined, letting them sit side by side and creating a multi-layered conceptual space for all our voices to talk to and through each other.

Could one say that Estonia’s chance to occupy the Rietveld Pavilion shaped the themes you could apply with for the Biennial?

In 2020, The Mondriaan Foundation invited Estonia, and more precisely the Estonian Center for Contemporary Art who commissions the artistic team on behalf of the Ministry of Culture, to take over the Dutch Pavilion located on the main exhibition grounds in the Giardini for the upcoming Biennale. For us this invitation was an incredible opportunity; I believe that there are no coincidences and we were meant to bring Orchidelirium to this space, as, together with Kristina Norman we had envisioned this exhibition even before the competition was announced. There were no conditions as to the theme of the proposals, and I know that other very talented artists who were shortlisted applied with projects that did not necessarily deal with Dutch heritage, or engage with the modernist architecture of the building. However, I believe the local and international jury made the right decision in picking our project as it turned out later that the themes of the Biennale The Milk of Dreams, curated by Cecilia Alemani perfectly aligned with the questions on botanical colonialisms in relationship with gender roles, and the entanglement of neocolonial structures with local politics that haunt us. I am very pleased with the effort of our artistic team, our commissioner, and the many collaborators from Indonesia, Europe and the US, who have guided us through this learning process, which has taught us a lot about ourselves and our heritage, working with integrity towards contexts outside of our own, and the importance of revealing hidden micro-histories to understand the consequences of our actions in the world.

The current Biennial revolved around the notion of identity more so than previous editions. In how far do you feel that the Estonian Pavilion fits into this direction?

The question of identity politics is a part of the story we are telling with the Estonian Pavilion, but it is not the main one. In fact, one of the impetus for putting this Pavilion together was to offer a counter to the discourse of the populist and radical right-wing party in Estonia, EKRE who enjoys massive popularity. I am very wary of how in the hands of these politicians, identity politics has been weaponized to act against refugees and immigration from certain contexts to Estonia. Their discourses are embedded in nationalism, and the collective memories of Soviet colonization, stroking the local collective anxieties about becoming colonized again by others. It is precisely why from the beginning the case-study of Emilie Saal intrigued us, not only because she was a woman in a patriarchal society that denied her recognition as an artist, but because she also tasted colonial ambition herself in Indonesia while coming from a colonized background in Estonia. She is an imperfect heroine, and her life story also mirrors the fate of Estonia itself, a small country on the outskirts of Europe, which became independent from Russia, and then, at least according to the politicians of the time, attempted to own colonies so that it would become “European.” These two realities coexisted in the interwar period, and I see reverberations of that mentality in Estonia today. We need to come to terms with our own histories, privileges and actions as constructs and responsibilities, even if thought of by others.

In the international art circuit, there are some Romanian spearheads, artists or curators that are like export products, on a pretty high level, contrasting with the precarious situation in Romania and the poverty of the main discourses in the local art scene. How do you see the Romanian contemporary art world from a distance and which people originally from the art world interest you?

When I left Romania to pursue a BA degree at Duke University I was not thinking about contemporary art or making a career in the arts at all. I was trained as a computer scientist, and later on discovered my passion for art, art history and curating. My first experience working with Romanian artists was assisting the mid-career retrospective of Lia and Dan Perjovschi at the Nasher Museum. The exhibition entitled States of Mind was curated by my then-advisor, Kristine Stiles. Over the years, I have both been mentored by Lia and Dan, and have collaborated with them; most recently I invited both of them to create site-specific commissions at the Tallinn Art Hall for my exhibition Making Another World Possible. Dan created a series of drawings commenting on local and regional politics directly on the glass windows of the Art Hall that face the famous Freedom Square in Tallinn, while Lia put together the installation ‘2020. Key Words’, including a chronology of events referring to the pandemic crisis and other world crises through the juxtaposition of texts, images, and objects with a series of notes and keywords that shape a subjective history revealing the artist’s particular view of our world. I have also worked together with Anca Benera and Arnold Estefan whom I invited to participate in the Shelter Festival Cosmopolitics, Comradeship and the Commons, at the Space for Free Arts in Helsinki (2019). I really appreciate their research-based practice that focuses on the invisible and hidden patterns behind historical, social, or geopolitical narratives. In addition to these artists, I have written about the work of Alexandra Pirici, Mona Vătămanu and Florin Tudor, Veda Popovici, among others.

I will continue to include Romania-based artists in my future exhibitions and events, as I see it important to support the local art scene that is facing increasing infrastructure difficulties and precarity. As strange as it may sound, I think people don’t even consider me as being part of the Romanian art world anymore, nonetheless, in the near future, I would like to contribute to the local art scene, debates and conversations there. Hopefully, after all these experiences working in different contexts, I could bring something meaningful to it and create some interesting dialogues between creative practitioners in Romania and the Baltics. We are at a very challenging moment in time, when the East-West conflicts begin to re-emerge and re-shape the foundation that has been laid in the last 30 years, and it is precisely at this moment that we need more collaboration and support between us.

[1] Kristina Madsen, Chto Delat: ‘Before you can recognise the light, you have to recognise the darkness’, Studio International, March 2017.

[2] Saal’s incomplete biographical references and part of her correspondences are archived at the Estonian Literary Museum.

[3] Emilie Rosalie Saal (1871-1954) was born in Tartu, and studied art in Petrograd (St. Petersburg), before living in Java between 1899 and 1920.

[4] Mark W. Chase, Maarten JM Christenhusz, and Tom Mirenda, “Orchidelirium,” in The Book of Orchids (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2021) 26–29.

[5] Sadiah Boonstra in conversation with the author online, March 2022.

POSTED BY

Bogdan Balan

Bogdan Bălan is a cultural journalist, art critic and cultural worker. He has collaborated with Goethe-Institut, Savvy Contemporary, Scena9, among others....

Comments are closed here.